The Great Escape (film)

| The Great Escape | |

|---|---|

_poster.jpg) | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Produced by | John Sturges |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on |

The Great Escape by Paul Brickhill |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 172 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $3.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $11,744,471 |

The Great Escape is a 1963 American World War II epic film that depicts an escape by British Commonwealth prisoners of war from a German POW camp. The film stars Steve McQueen, James Garner, and Richard Attenborough and features James Donald, Charles Bronson, Donald Pleasence, James Coburn, and Hannes Messemer. It was filmed in Panavision.

The film is based on Paul Brickhill's 1950 book of the same name, a non-fiction first-hand account of the mass escape from Stalag Luft III in Sagan (now Żagań, Poland), in the province of Lower Silesia, Nazi Germany. A heavily fictionalised version of the escape is depicted in the film. The film was based on the real events but with numerous compromises for its commercial appeal, such as including Americans among the escapees (none of whom were actually American). The characters are based on real men, and in some cases are composites of several men. However, many details of the actual escape attempt were changed for the film, and the role of American personnel in both the planning and the escape was largely fabricated. The Great Escape was made by The Mirisch Company, released by United Artists, and produced and directed by John Sturges.

The film had its Royal World Premiere at the Odeon Leicester Square in London's West End on 20 June 1963.[2]

Plot

In 1943, having expended enormous resources on recapturing escaped Allied POWs, the Germans move those POWs under their senior British officer, Group Captain Ramsey, most determined to escape to a new, high-security prisoner of war camp under the supervision of Luftwaffe Colonel von Luger. Meanwhile, Gestapo agents Kuhn and Preissen and SS Lieutenant Dietrich bring RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett to the camp. Known as "Big X", Bartlett is introduced as the principal escape organiser. As Kuhn leaves, he warns Bartlett that if he escapes again, he will be shot. Bartlett remains defiant and immediately plans the greatest escape ever attempted, with tunnels to break out 250 prisoners.

The POWs organise into teams. Flight Lieutenant Robert Hendley is "the scrounger" who finds needed materials, from a camera to clothes and identity cards. Australian Flying Officer Louis Sedgwick, "the manufacturer", makes tools like picks for digging and bellows for pumping air into the tunnels. Flight Lieutenants Danny Velinski and William "Willie" Dickes are "the tunnel kings" in charge of the digging. Flight Lieutenant Andrew MacDonald acts as intelligence provider and Bartlett's second-in-command. Lieutenant Commander Eric Ashley-Pitt of the Royal Navy devises a method of spreading soil from the tunnels over the camp, under the guards' noses. Flight Lieutenant Griffith acts as "the tailor", creating civilian outfits from scavenged cloth. Forgery is handled by Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe. The prisoners work on three tunnels simultaneously, calling them "Tom", "Dick", and "Harry".

USAAF Captain Virgil Hilts, the "Cooler King", irritates guards with frequent escape attempts and irreverence. Hilts and his Scottish friend, RAF Flying Officer Archibald "Archie" Ives, conceive an escape attempt through a short tunnel at a blind spot near the edge of the camp, a proposal which is accepted by Bartlett on the grounds that vetoing every independent escape attempt would raise suspicion of the planned collective escape attempt. Hilts and Ives are caught and returned to the "cooler". Upon release from the cooler, Bartlett requests that Hilts use his next escape attempt as an opportunity to reconnoiter the area immediately surrounding the camp; Hilts turns down Bartlett's request but does assist the prisoners as a scrounger. Meanwhile, Hendley forms a friendship with German guard Werner, which he exploits to smuggle documents and other items of importance to the prisoners. Soon, Bartlett orders "Dick" and "Harry" to be sealed off, as "Tom" is closest to completion.

While the POWs enjoy a 4th of July celebration arranged by the three Americans in the camp, the guards discover "Tom". The mood drops to despair, and Ives frantically climbs the barbed wire surrounding the camp, to be shot dead. The prisoners switch their efforts to "Harry", and Hilts agrees to reconnoiter outside the camp and allow himself to be recaptured. The information he brings back is used to create maps to guide the escapees. Blythe becomes nearly blind due to progressive myopia caused by intricate work by candlelight; Hendley takes it upon himself to be Blythe's guide in the escape.

The last part of the tunnel is completed on the scheduled night, but it proves to be twenty feet short of the woods. Knowing there are no other options, Bartlett orders the escape to go ahead, and Hilts improvises a rope signal system to allow them to exit the tunnel between sweeps of the guards on patrol. Seventy-six prisoners escape, aided by an air-raid blackout: once back on the rope, however, Griffith impatiently exits the tunnel in view of the guards, and the escape is discovered.

After attempts to reach neutral Switzerland, Sweden, or Spain, almost all the POWs are recaptured or killed. Hendley and Blythe steal a plane to fly over the Swiss border, but the engine fails, and they crash-land. Soldiers surround them and Blythe, his eyesight damaged, stands and is shot. As Blythe dies, he thanks Hendley for getting him out.

When Bartlett is recognized in a railway station by Kuhn, Ashley-Pitt rushes Kuhn and shoots him, but is killed while attempting to flee. The resulting confusion allows Bartlett and MacDonald to slip away, but they are later caught as well. Hilts steals a motorcycle at a checkpoint and is pursued by German soldiers. He jumps a first-line barbed wire fence at the German-Swiss border; but before he's able to jump the second-line fence, the motorcycle is shot, causing him to become entangled in the bigger, second line of the fence and be captured.

Three truckloads of recaptured POWs are driven down a country road and split off in three directions. The trucks stop in a field, and the POWs, which include Bartlett, MacDonald, Cavendish and Haynes, are told to get out to "stretch their legs". The prisoners are shot dead under the pretense that they were trying to escape. In all, 50 escapees are murdered; Hendley and 10 others are returned to the camp.

Only three POWs make it to safety: Danny and Willie steal a rowboat and proceed downriver to the Baltic coast, where they board a Swedish merchant ship. Sedgwick makes it to France, where he is guided by the Resistance to Spain. Hilts is returned to the camp and taken back to the cooler, just as Von Luger is relieved of command of the camp by SS Lieutenant Steinach, with the indication that he will be executed for having failed to prevent the breakout. The film closes with a caption reading, "This picture is dedicated to the fifty".

Cast

- Steve McQueen as Hilts "The Cooler King"

- James Garner as Hendley "The Scrounger"

- Richard Attenborough as Bartlett "Big X"

- James Donald as Ramsey "The SBO"

- Charles Bronson as Danny "Tunnel King"

- Donald Pleasence as Blythe "The Forger"

- James Coburn as Sedgwick "Manufacturer"

- Hannes Messemer as Von Luger "The Kommandant"

- David McCallum as Ashley-Pitt "Dispersal"

- Gordon Jackson as MacDonald "Intelligence"

- John Leyton as Willie "Tunnel King"

- Angus Lennie as Ives "The Mole"

- Nigel Stock as Cavendish "The Surveyor"

- Robert Graf as Werner "The Ferret"

- Jud Taylor as 2nd Lt. Goff

- Hans Reiser as Kuhn (Gestapo)

- Harry Riebauer as Stabsfeldwebel Strachwitz

- William Russell as Sorren

- Robert Freitag as Hauptmann Posen

- Ulrich Beiger as Preissen

- George Mikell as SS Obersturmführer Dietrich

- Lawrence Montaigne as Haynes "Diversions"

- Robert Desmond as Griffith "Tailor"

- Til Kiwe as Frick

- Heinz Weiss as Kramer

- Tom Adams as Dai Nimmo "Diversions"

- Karl-Otto Alberty as SS Untersturmführer Steinach

Production

Adaptation

The story was adapted by James Clavell, W. R. Burnett, and Walter Newman from Paul Brickhill's book The Great Escape. Brickhill had been a prisoner at Stalag Luft III during World War II. In the book, Brickhill noted he had been a very minor member of the X Organization, one of the "stooges" who monitored German movements in the POW compound.

The film was to a significant extent fictional, based on real events but with numerous changes made to increase its drama and appeal, and as a vehicle for its box-office stars. While some of its characters were fictitious, most were amalgams of several real characters and others based on real people. In reality there were no escapes by aircraft or motorcycle: the motorcycle sequence was asked for by McQueen, a keen motorcyclist, who did the stunt riding himself (except for the final jump, done by Bud Ekins).[3] Nor were the recaptured prisoners executed in one place at the same time. The screenwriters significantly increased the involvement of American POWs; the real escape was by largely British and other Allied personnel. A few American officers in the camp initially helped dig the tunnels, and worked on the early plans; however, they were moved away seven months before the escape, ending their involvement.[4][5][6] In addition, the film suggests the three prisoners who escaped to freedom were British, Polish, and Australian; in reality, they were Norwegian (Jens Müller and Per Bergsland) and Dutch (Bram van der Stok).[7]

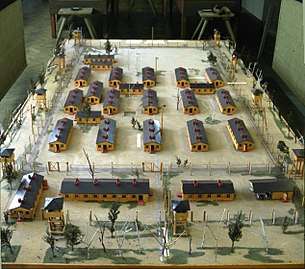

The film omits to mention the crucial role Canadians played in building the tunnels and in the escape itself. Of the 1,800 or so POWs, 600 were involved in preparations out of which 150 were Canadian. Wally Floody, an RCAF pilot and mining engineer who was the real-life "tunnel king," was engaged as a technical advisor for the film.[8]

Ex-POWs asked film-makers to exclude details about the help they received from their home countries, such as maps, papers, and tools hidden in gift packages, lest it jeopardise future POW escapes. The film-makers complied.[9]

The film omits to mention that many Germans willingly helped in the escape itself. The film suggests that the forgers were able to make near-exact replicas of just about any pass that was used in Nazi Germany. In reality, the forgers received a great deal of assistance from Germans who lived many hundreds of miles away on the other side of the country. Several German guards, who were openly anti-Nazi, also willingly gave the prisoners items, and assistance in any way to aid their escape.[10]

The need for such accuracy produced much eyestrain, but unlike in the film, there were no cases of blindness. Some, such as Frank Knight, gave up forging because of the strain, but he certainly did not suffer the same ocular fate as the character of Colin Blythe in the film.[10]

Casting

Steve McQueen, in a role based on at least three pilots, David M. Jones, John Dortch Lewis,[11] and William Ash,[12][13][14] has been credited with the most significant performance. Critic Leonard Maltin wrote that "the large, international cast is superb, but the standout is McQueen; it's easy to see why this cemented his status as a superstar."[15]

Richard Attenborough was cast as Sqn Ldr Roger Bartlett RAF ("Big X"), a character based on Roger Bushell, the South African-born British POW who was the mastermind of the real Great Escape.[16] This was the film that first brought Attenborough to wide popular attention in the United States. During the Second World War, Attenborough served in the Royal Air Force. He volunteered to fly with the Film Unit and after further training, where he sustained permanent ear damage, qualified as a sergeant, flying on several missions over Europe filming from the rear gunner's position to record the outcome of Bomber Command sorties. (Richard Harris was originally announced for the role.[17])

Group Captain Ramsey RAF (the "SBO") was based on Group Captain Herbert Massey, a WWI veteran who had volunteered in WWII. He is played by James Donald. Massey walked with a limp, and so did Ramsey in the movie who walked with a cane. Massey had suffered severe wounds to the same leg in both wars. There would be no escape for him but as Senior British Officer, he had to know what was going on. Group Captain Massey had been a veteran escaper himself and had been in trouble with the Gestapo. His experience allowed him to offer sound advice to the X-Organisation.[18] Another officer that had most likely inspired the character of Ramsey was Wing Commander Harry Day. There was an uncanny resemblance between "Wings" Day and James Donald as Group Captain Ramsey in this picture.

Flt Lt Colin Blythe RAF ("The Forger") was based on Tim Walenn and played by Donald Pleasence.[19] Pleasence himself had served in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He was shot down and spent a year in German prisoner-of-war camp Stalag Luft I.

Charles Bronson had been a gunner in the USAAF and was wounded, but had not been shot down. Like his character, Danny Valinski, he was a coal miner and suffered from claustrophobia.

James Garner had been a soldier in the Korean War and was twice wounded. He was a scrounger during that time, as is his character Flt Lt Hendley.[20]

Hannes Messemer was cast as the Kommandant of Stalag Luft III, "Colonel von Luger," a character based on Oberst Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau.[21] He had been a POW in Russia during World War II and had escaped by walking hundreds of miles to the German border.[22]

Angus Lennie's Flying Officer Archibald Ives, "The Mole", was based on Jimmy Kiddel, who was shot dead while trying to scale the fence.[23]

The film is accurate in showing that only three escapees made home runs, although the people who made them differed from those in the film. The escape of Danny and Willie in the film is based on two Norwegians who escaped by boat to Sweden, Per Bergsland and Jens Müller. The successful escape of James Coburn's Australian character Sedgwick (the manufacturer) via Spain was based on Dutchman Bram van der Stok. Coburn, an American, was cast in the role of Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Flying Officer Louis Sedgwick who was an amalgamation of Flt Lt Albert Hake, an Australian serving in the RAF and the camps compass maker, and Johnny Travis, the real manufacturer.

Tilman 'Til Kiwe' Kiver played the German guard "Frick". He is the one who fires his pistol at Steve McQueen's character during the escape. Kiwe had been a German paratrooper officer who was captured and held prisoner at a POW camp in Colorado. He made several escape attempts, dyeing his uniform and carrying forged papers. He was captured in the St. Louis train station during one escape attempt. He won the Knight's Cross before his capture and was the cast member who had actually done many of the exploits shown in the film.

Location and set design

The film was made at the Bavaria Film Studio in the Munich suburb of Geiselgasteig in rural Bavaria, where sets for the barrack interiors and tunnels were constructed. The camp was built in a clearing of the Perlacher forest near the studio.[24][25] The German town near the real camp was Sagan (now Żagań, Poland); it was renamed Neustadt in the film.[25] Many scenes were filmed in and around the town of Füssen in Bavaria, including its railway station. The nearby district of Pfronten[26] with its distinctive St. Nikolaus Church and scenic background also features often in the film.[25] Many scenes involving the railway were filmed near Deisenhofen station and on the Großhesselohe - Holzkirchen line.[27] The castle Hendley and Blythe fly by while attempting to escape is Neuschwanstein Castle.[28]

The film depicts the tunnel codenamed Tom as having its entrance under a stove and Harry's as in a drain sump in a washroom. In reality, Dick's entrance was the drain sump, Harry's was under the stove, and Tom's was in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney.[29]

The motorcycle chase scenes with the barbed wire fences were shot on meadows outside Füssen, and the "barbed wire" that Hilts crashes into before being recaptured was simulated by strips of rubber tied around barbless wire, constructed by the cast and crew in their spare time.[30] The final jump scene was performed by stuntman Bud Ekins in place of Steve McQueen. Other parts of the chase were done by McQueen, playing both Hilts and the soldiers chasing him, because of his ability on a motorcycle.[31] The motorcycle was a Triumph TR6 Trophy which was painted to look like a German machine. The restored machine is currently on display at Triumph's factory at Hinckley, UK.[32]

Music

Intrada Records album

Disc one

| Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:30 |

| 2. | "At First Glance" | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Premature Plans" | 2:28 |

| 4. | "If At Once" | 2:31 |

| 5. | "Forked" | 1:28 |

| 6. | "Cooler" | 1:59 |

| 7. | "Mole" | 1:28 |

| 8. | ""X"/Tonight We Dig" | 1:30 |

| 9. | "The Scrounger/Blythe" | 3:50 |

| 10. | "Water Faucet" | 1:23 |

| 11. | "Interruptus" | 1:33 |

| 12. | "The Plan/The Sad Ives" | 1:43 |

| 13. | "Green Thumbs" | 2:28 |

| 14. | "Hilts And Ives" | 0:38 |

| 15. | "Cave In" | 2:01 |

| 16. | "Restless Men" | 1:56 |

| 17. | "Booze" | 1:47 |

| 18. | ""Yankee Doodle"" | 0:55 |

| 19. | "Discovery" | 3:40 |

Disc two

| Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (Cont'd) | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Various Troubles" | 3:52 |

| 2. | "Panic" | 2:05 |

| 3. | "Pin Trick" | 0:59 |

| 4. | "Hendley’s Risk" | 1:43 |

| 5. | "Released Again/Escape Time" | 5:25 |

| 6. | "20 Feet Short" | 3:06 |

| 7. | "Foul Up" | 2:37 |

| 8. | "At The Station" | 1:33 |

| 9. | "On The Road" | 3:27 |

| 10. | "The Chase/First Casualty" | 6:49 |

| 11. | "Flight Plan" | 2:09 |

| 12. | "More Action/Hilts Captured" | 6:07 |

| 13. | "Road’s End" | 2:06 |

| 14. | "Betrayal" | 2:20 |

| 15. | "Three Gone/Home Again" | 3:13 |

| 16. | "Finale/The Cast" | 2:47 |

Disc three

| Original 1963 United Artists Score Album | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Premature Plans" | 2:08 |

| 3. | "Cooler And Mole" | 2:26 |

| 4. | "Blythe" | 2:13 |

| 5. | "Discovery" | 2:54 |

| 6. | "Various Troubles" | 2:40 |

| 7. | "On The Road" | 2:54 |

| 8. | "Betrayal" | 2:05 |

| 9. | "Hendley’s Risk" | 2:24 |

| 10. | "Road’s End" | 2:00 |

| 11. | "More Action" | 1:57 |

| 12. | "The Chase" | 2:49 |

| 13. | "Finale" | 3:14 |

Reception

The Great Escape grossed $11.7 million at the box office,[33] after a budget of $4 million.[34] It became one of the highest-grossing films of 1963, despite heavy competition. In the years since its release, its audience has broadened, cementing its status as a cinema classic.[35] It was entered into the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival where McQueen won the Silver Prize for Best Actor.[36]

Critical and public response has mostly been enthusiastic, with a 93% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[37] In 1963 New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote: "But for much longer than is artful or essential, The Great Escape grinds out its tormenting story without a peek beneath the surface of any man, without a real sense of human involvement. It's a strictly mechanical adventure with make-believe men."[38] British film critic Leslie Halliwell described it as "pretty good but overlong POW adventure with a tragic ending".[39] In Time magazine 1963: "The use of color photography is unnecessary and jarring, but little else is wrong with this film. With accurate casting, a swift screenplay, and authentic German settings, Producer-Director John Sturges has created classic cinema of action. There is no sermonizing, no soul probing, no sex. The Great Escape is simply great escapism".[40]

In a 2006 poll in the United Kingdom, regarding the family film that television viewers would most want to see on Christmas Day, The Great Escape came in third, and was first among the choices of male viewers.[41]

In 2009, seven POWs returned to Stalag Luft III for the 65th anniversary of the escape[42] and watched the film. According to the veterans, many details of the first half depicting life in the camp were authentic, e.g. the machine-gunning of Ives, who snaps and tries to scale the fence, and the actual digging of the tunnels. In 2014, the 70th anniversary of the escape, the RAF staged a commemoration of the escape attempt, with 50 serving personnel carrying a photograph of one of the men shot.[43]

The film has resulted in the story and the memory of the fifty executed airmen remaining widely known, if in a distorted form.[44]

Awards and honors

- Nominated Academy Award for Film Editing (Ferris Webster)

- Nominated Golden Globe Award for Best Picture

- Winner Moscow International Film Festival Best Actor (Steve McQueen)

- Nominated Moscow International Film Festival Grand Prix (John Sturges)

- Selected National Board of Review Top Ten Films of Year

- Nominated Writers Guild of America Best Written American Drama (James Clavell, W. R. Burnett) (Screenplay Adaptation)

In popular culture

References to scenes and motifs from the film, as well as Elmer Bernstein's theme, have appeared in other films, television series, and video games.

Film

- The films Chicken Run, Reservoir Dogs, the 1998 remake of The Parent Trap, Top Secret!, and Charlie's Angels all contain references or homages to the film.[45]

Television

- Monty Python's Flying Circus, The Simpsons, Hogan's Heroes, Nash Bridges, Seinfeld, Get Smart, and Red Dwarf have all parodied or paid homage to the film.[45]

- In "Escape From Stalag Luft 112B," an episode of Ripping Yarns, Maj. Errol Phipps (played by Michael Palin) is depicted as being the only prisoner of war never to escape from the camp of the title.[45]

- A fictional, made-for-television sequel, The Great Escape II: The Untold Story, appeared in 1988. It starred Christopher Reeve and Judd Hirsch. Donald Pleasence in a supporting role plays a member of the SS (in the 1963 original Pleasence had played Flight-Lieutenant Colin Blythe, 'The Forger').[45] The film is not a true sequel, as it dramatizes the escape itself just as the original film does, although mostly using the real names of the individuals involved (whereas the original film fictionalized them and used composite characters). The murder of the prisoners in this film is more accurate than in the 1963 original, with the POWs being shot individually or in pairs, but other portions of the film are fictional. It depicts the search for those responsible for the murder of the Allied officers, and the subsequent trials.

Video games

- The 1986 video game The Great Escape for the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum and DOS platforms, shares a title and similar plot to the movie. The game follows an unnamed prisoner of war who has been interned in a P.O.W. camp somewhere in northern Germany in 1942.

- The 2003 video game The Great Escape for Xbox and PlayStation 2, is based on the film. The plot-line follows that of the film of the same name, except there are also levels featuring some of the characters first captures and early escape attempts, as well as a changed ending.

Sport

- Bernstein's Great Escape theme tune has been taken up by the Pukka Pies England Band, a small brass band who have played in the crowd at England football team matches since 1996.[46] They released an arrangement of the theme as a single for the 1998 FIFA World Cup and a newer version for UEFA Euro 2000.[47]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780299114404.

- ↑ "The Great Escape, premiere". The Times. London. June 20, 1963. p. 2.

- ↑ Brissette, Pete (July 15, 2005). "Steve McQueen 40 Summers Ago..." Motorcycle.com. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Wolter, Tim (2001). POW baseball in World War II. McFarland. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-7864-1186-3.

- ↑ Craig, Phil (October 24, 2009). "He shot the hero of the Great Escape in cold blood. But was this one Nazi who DIDN'T deserve to hang?". Daily Mail Online. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Brickhill, Paul, The Great Escape

- ↑ Hansen, Magne; Carlsen, Marianne Rustad (February 26, 2014). "Hollywood droppet nordmenn" [Hollywood dropped Norwegians]. NRK (in Norwegian). Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Canadians and the Great Escape". Canada at War. July 11, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ The Great Escape: Heroes Underground documentary, available on The Great Escape DVD Special Edition.

- 1 2 Walters, Guy (2013). The Real Great Escape. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-0-593-07190-8.

- ↑ Kaufman, Michael T. (August 13, 1999). "John D. Lewis, 84, Pilot in 'The Great Escape'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Bishop, Patrick (30 August 2015). "William Ash: The cooler king". BBC Online. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Foley, Brendan (29 April 2014). "Bill Ash obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ "William Ash - obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard (1999). Leonard Maltin's Family Film Guide. New York: Signet. p. 225. ISBN 0-451-19714-3.

- ↑ Whalley, Kirsty (November 10, 2008). "Escape artist's inspiring exploits". This is Local London. Newsquest Media Group / A Gannett Company. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ 'Mutiny' Director Find Make Deals: Bogarde in 'Living Room'; Du Pont Scion Plans Three Scheuer, Philip K. Los Angeles Times 2 Mar 1962: C13.

- ↑ Gill, Anton (2002). The Great Escape. London: Review. p. 96. ISBN 9780755310388.

- ↑ Vance 2000, p. 44: "Now sporting a huge, bushy moustache ... he set to work arranging the operations of the forgery department"

- ↑ DVD extra

- ↑ Carroll, Tim (2004). The Great Escapers. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-904-5.

- ↑ "Combat Films: American Realism, 1945-2010, 2d ed. - Steven Jay Rubin - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Hall, Allan (March 24, 2009). "British veterans mark Great Escape anniversary". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ↑ Riml, Walter (2013). Behind the scenes... The Great Escape. Helma Turk & Dr. Christian Riml. pp. 28, 44ff. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Whistance, Don J. (2014). "The Great Escape Locations Site". thegreatescapelocations.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Riml (2013), p.110ff.

- ↑ Riml (2013), p.58ff.

- ↑ Warren, Jane. "The Truth About The Great Escape | Express Yourself | Comment | Daily Express". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Vance 2000, pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Rufford, Nick (February 13, 2009). "Video: The Great Escape, re-enacted". The Times. Times Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Stone, Matt (2007). McQueen's Machines: The Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. Minneapolis, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7603-38957.

There's a chase sequence in there where the Germans were after [McQueen], and he was so much a better rider than they were, that he just ran away from them. And you weren't going to slow him down. So they put a German uniform on him, and he chased himself!

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leicestershire-41809557

- ↑ "The Great Escape - Box Office Data". The Numbers. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Lovell, Glenn (2008). Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 224.

- ↑ Eder, Bruce (2009). "Review: The Great Escape". AllMovie. Macrovision Corporation. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ↑ "3rd Moscow International Film Festival (1963)". MIFF. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ↑ "The Great Escape". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (August 8, 1963). "P.O.W.'s in 'Great Escape':Inmates of Nazi Camp Are Stereotypical – Steve McQueen Leads Snarling Tunnelers". The New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ↑ Walker, John (1997). "Halliwell's Film and Video Guide". London: HarperCollins: 311. ISSN 1098-206X.

- ↑ "Cinema: The Getaway". Time. Time Inc. July 19, 1963. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ↑ "TV classics are recipe for Christmas Day delight". Freeview. December 11, 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ↑ Paterson, Tony (March 25, 2009). "Veterans of the Great Escape visit old Stalag". The Independent. London: INM. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Hall, Robert (March 24, 2014). "'The Great Escape' commemorated in Poland". BBC News. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Warren, Jane. "The Truth About The Great Escape | Express Yourself | Comment |". The Daily Express. Northern andShell Media. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Nixon, Rob (2008). "Pop Culture 101: The Great Escape". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ↑ Walters, Mike. "Exclusive interview with The Pukka Pie England Band". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ↑ "ChartArchive – England Supporters' Band". Chartstats.com. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Allen (1976). Exemplary Justice. London: Harrap. ISBN 0245527753. Details the manhunt by the Royal Air Force's special investigations unit after the war to find and bring to trial the perpetrators of the "Sagan murders".

- Barris, Ted (2013). The Great Escape: A Canadian Story. Toronto: Thomas Allen. ISBN 1771022728.

- Brickhill, Paul (1950). The Great Escape. New York: Norton.

- Burgess, Alan (1990). The Longest Tunnel. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 1555840337.

- Hehner, Barbara (2004). The Tunnel King: The True Story of Wally Floody and the Great Escape. Toronto: Harper Trophy Canada.

- Hevesi, Dennis (April 22, 2012). "Alex Cassie of 'Great Escape' Dies at 95". The New York Times. p. 20.

- Müller, Jens (1946). Tre kom tilbake [Three returned]. Norway: Gyldendal. Memoir by the surviving Norwegian escapee.

- Smith, Sydney (1968). 'Wings' Day. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-02494-9. Story of Wing Commander Harry "Wings" Day.

- Vance, Jonathan F. (2000). A Gallant Company: The True Story of the Man of "The Great Escape". New York: I Books. ISBN 978-0739442425.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Great Escape (film) |

- The Great Escape on IMDb

- The Great Escape at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Escape at AllMovie

- The Great Escape at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Great Escape at Box Office Mojo

- James Garner Interview on the Charlie Rose Show (See 30:23–34:47 of video.)

- New publication with private photos of the shooting & documents of 2nd unit cameraman Walter Riml

- Photos of the filming

- The Great Escape locations

- The Great Escape at Rotten Tomatoes