The Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature

The Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature (Tamil: ஐம்பெரும்காப்பியங்கள் Aimperumkāppiyaṅkaḷ) are five large narrative Tamil epics according to later Tamil literary tradition. They are Cilappatikāram, Manimekalai, Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi, Valayapathi and Kuṇṭalakēci.[1] The first mention of the Aimperumkappiyam (lit. Five large epics) occurs in Mayilainathar's commentary of Nannūl. However, Mayilainathar does not mention their titles. The titles are first mentioned in the late 18th–early 19th century work Thiruthanikaiula. Earlier works like the 17th century poem Tamil vidu thoothu mention the great epics as Panchkavyams.[2][3] Among these, the last two, Valayapathi and Kuṇṭalakēci are not extant.[4]

These five epics were written over a period of 1st century CE to 10th century CE and act as the historical evidence of social, religious, cultural and academic life of people during the era they were created. Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi introduced long verses called virutha pa in Tamil literature,[5] while Cilappatikāram used akaval meter (monologue), a style adopted from Sangam literature.

Style

According to the great Tamil commentator Atiyarkkunallar (12th–13th century CE), poems were of two kinds – Col thodar nilai ceyyuḷ (சொல் தொடர் நிலை செய்யுள்) or poems connected by virtue of their formal properties and Poruḷ toṭar nilai ceyyuḷ (பொருள் தொடர் நிலை செய்யுள்) or poems connected by virtue of content that forms a unity.[6][7] Cilappatikāram, the Tamil epic is defined by Atiyarkkunallar as Iyal icai nāṭaka poruḷ toṭar nilai ceyyuḷ (இயல் இசை நாடக பொருள் தொடர் நிலை செய்யுள்), poems connected by virtue of content that forms a unity having elements of poetry, music and drama.[6][7] Such stanzas are defined as kāvya and kappiyam in Tamil. In Mayilainathar's commentary (14th century CE) on the grammar Nannūl, we first hear the mention of aimperumkappiyam, the five great epics of Tamil literature.[6]

Each one of these epics have long cantos, like in Cilappatikāram, which has 30 referred as monologues sung by any character in the story or by an outsider as his own monologue often quoting the dialogues he has known or witnessed.[8] It has 25 cantos composed in akaval meter, used in most poems in Sangam literature. The alternative for this meter is called aicirucappu (verse of teachers) associated with verse composed in learned circles.[9] Akaval is a derived form of verb akavu indicating to call or beckon. Cilappatikāram is credited with bringing folk songs to literary genre, a proof of the claim that folk songs institutionalised literary culture with the best-maintained cultures root back to folk origin.[9] Manimekalai is an epic in ahaval metre and is noted for its simple and elegant style of description of natural scenery.[10] Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi is one of the earliest works of Tamil literature in long verses called virutha pa.[5]

| No | Name | Author | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cilappatikāram | Ilango Adigal | Non-religious work of 1st century CE[4] |

| 2 | Manimekalai | Sīthalai Sāttanār | Buddhist religious work of 1st or 5th century CE[4] |

| 3 | Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi | Tirutakkatevar | Jain religious work of 10th century CE[4] |

| 4 | Valayapathi | Unknown Jain ascetic | Jain religious work of 9th century CE[4] |

| 5 | Kundalakēci | Naguthanar | Buddhist religious work of 5th century CE[4] |

Theme

The epic trio of Cilappatikāram, Manimēkalai and Cīvaka Cintāmani gives a full account of Tamil concept of womanhood by powerfully and poignantly delineating the character of a chaste wife Kannagi, a brave and dutiful daughter Manimekalai, and an affectionate mother in Vijayai, mother of Jivakan in the three epics respectively.[12]

Cilappatikāram explains the inexorable working of fate where, in spite of being innocent, the hero Kovalan gets punished and the queen of Pandya loses her life along with the king when the king realises his mistake of punishing Kovalan.[13] Kannagi is regarded as a symbol of chastity and she is always associated with chasteness in Tamil literature across ages.

In Maniṇmēkalai, the protagonist, Manimēkalai is instructed in the truths expounded by the teachers of different faiths.[13]

Cīvaka Cintāmani, adopted from Sanskrit Mahapurana, is predominantly sensuous, though Jain philosophy is brought to practical aspects of life.[13]

Stories

Cilappatikāram (“The Tale of an Anklet”) depicts the life of Kannagi, a chaste woman who lead a peaceful life with Kovalan in Puhar (Poompuhar), the then-capital of the Chola dynasty. Her life later went astray by the association of Kovalan with an unchaste woman Madhavi. The duo started resurrecting their life in Madurai, the capital of Pandyas. Kovalan went on to sell the anklet of Kannagi to start a business but was held guilty and beheaded of stealing it from the queen. Kannagi want to prove the innocence of her husband and believed to have burnt the entire city of Madurai by her chastity. Apart from the story, it is a vast treasury of music and dance, both classical and folk.[14]

Manimekalai is a 5th-century Buddhist epic created by Sithalai Sathanar. It is believed to be a followup of Cilappatikāram with the primary character, Maṇimēkalai being the daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi. It contains thirty cantos describing the circumstances in which Maṇimēkalai renounced the world and took the vows of Theravada sect of Buddhism, which is followed in Burma and Sri Lanka.[15] Apart from the story of Maṇimēkalai and her Buddhist inclination, the epic deals with a great deal with the Buddha's life, work and philosophy.[14]

Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi, an epic of the 10th century CE was written by Thiruthakka Thevar, a Jain monk. It narrates the romantic exploits of Jeevaka and throws light on arts of music and dance of the era. It is reputed to have been the model for Kamba Ramayanam.[14] The epic is based on a Sanskrit original and contains the exposition of Jain doctrines and beliefs. It is a mudi-porul-thodar-nilai-seyyul: a treatise of the fourfold object of life and aim of literary work of virtue, wealth, pleasure and bliss.[16] It has 13 books or illambagams and contains 3147 stanzas. It is noted for its chaste diction and sublime poetry rich in religious sentiments and replete with information of arts and customs of social life.[16][17] There are many commentaries on the book; the best on the work is believed to be by Naccinarkiniyar.[17]

Kuṇṭalakēci is now lost, but there are quotations from it and found from references used by authors who had access to the classic.[18] The poem demonstrated the advantage of Buddhism over Shrauta and Jainism.[18] The Jain in reply wrote Nilakesi which has opposing views to the ideologies in Kuṇṭalakēci. Kuṇṭalakēci was a Jain nun who moved around India, expounding Jainism and challenged anyone who had alternate views. Sāriputta, a disciple of Gautama Buddha, took up the challenge one day and defeated Kuṇṭalakēci in debates. She renounced Jainism and became a Buddhist.[18] The author is believed to be Nagaguttanar.[18] The record of culture and Buddhist views during the era were lost with the book.[18]

Vaḷaiyāpati is another lost work; it is unclear whether it is a Buddhist or Jain.[19] Some scholars believe it is a Buddhist work and base their claims on the quotations of Vaḷaiyāpati found in other literary works.[19] The author of Vaḷaiyāpati quotes from Tirukkuṟaḷ, and it is possible that he took inspiration from it.[19]

Age and genre

Cilappatikāram and Maṇimēkalai are accepted to be composed after the Sangam period (300 BCE to 200 CE). M. Varadarajan assessed the period to be between 100–500 CE, T.P. Meenakshi Sundaram as 5th century CE, Somasundaram Pillai calls in age of Buddhism and Jainism and places between 250 CE and 600 CE, and Rajamanickam places both these in the 2nd century CE.[20] Maṇimēkalai has been accepted as a sequel of Cilappatikāram and they are placed before the 5th century CE.[20] It is generally accepted that these works might have been composed between 200 BCE to 500 CE.[20]

There is a controversy to the age of the author of Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi: Tirutakkatevar. There is one version that he lived before Kamban (9th century CE) as the viruttam metre, language and imagery was commonly used by Kamban. The other view is that it belongs to a period later than Kamban.[12]

Parallels with Sanskrit literature

It was the period when ornate Sanskrit literature evolved and shared major features with Tamil literature. The period of Pallava supremacy is characterized by the development of epic poetry. The use of nature to express ideas or feelings is first introduced in Cilappatikāram.[21] The two Tamil epics, Cilappatikāram and Maṇimēkalai do not use the convention of the land divisions becoming part of description of life among communities of hero and heroine.[21] The epics mention the evenings and spring season in particular as time and season that aggravates the feelings in those who are separated.[21]

These patterns are found only in the later works of Sanskrit by Kalidasa (10th century CE).[21] The epic style of Sanskrit was emulated with characterization of ordinary people like Kovalan and Kannagi, providing an insight into everyday life during the period.[22]

Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi emulates Sanskrit court poetry and illustrates the heroics of Civaka, who later becomes a monk.[22] Cilappatikāram posts a line of development of long poetic sequence in Tamil literature and downplays points of derivation from Sanskrit contemporary works like Mahakavya.[23] Cilappatikāram and Maṇimēkalai thus showed greater specialities compared to its Sanskrit counterparts during the period.[4]

Religious treatise

The influence of Vedic religion was marked in the religious life of the people in the south. The followers of Veda often entered into dispute with rival religions like Buddhism and Jainism.[24] Hinduism was prevalent during the 1st century CE followed by Buddhism in the next three centuries, and Jainism taking prominence during the 5th–6th centuries CE.[24] This is well illustrated in the non-religious work of Cilappatikāram written during the 1st century CE followed by Buddhist work of Maṇimēkalai and the Jain work of Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi. The joyous life portrayed in Sangam literature is replaced by sombre life depicted in Maṇimēkalai.[24] It depicts punishments to people who, knowing the inevitability, of death indulge in crimes and carnal pleasures.[24]

Five minor Tamil epics

Similar to the five great epics, Tamil literary tradition classifies five more works as Ainchirukappiyangal (Tamil: ஐஞ்சிறுகாப்பியங்கள்) or five minor epics. The five lesser Tamil epics are Neelakesi, Naga kumara kaviyam, Udhyana kumara Kaviyam, Yasodhara Kaviyam and Soolamani.[1][25]

Publishing in modern times

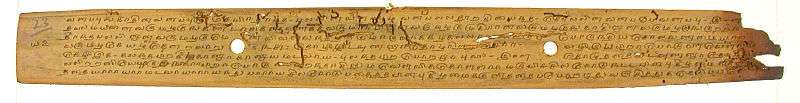

U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (1855–1942 CE) resurrected the first three epics from appalling neglect and wanton destruction of centuries.[14] He reprinted the literature present in the palm leaf form to paper books.[26] Ramaswami Mudaliar, a Tamil scholar first gave him the palm leaves of Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi to study.[14] Being the first time, Swaminatha Iyer had to face a lot of difficulties in interpreting, missing leaves, textual errors and unfamiliar terms.[14] He set for tiring journeys to remote villages in search of the missing manuscripts. After years of toil, he published Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in book form in 1887 CE followed by Cilappatikāram in 1892 CE and Manimekalai in 1898 CE.[14] Along with the text, he added much commentary and explanatory notes of terms, textual variations and approaches explaining the context.[14]

Criticism and comparison

"After the last line of a poem, nothing follows except literary criticism," observes Iḷaṅkō Aṭikaḷ in Cilappatikāram. The postscript invites readers to review the work. Like other epic works, these works are criticised of having an unfamiliar and difficult poem to understand.[27] To some critics, Maṇimēkalai is more interesting than Cilappatikāram, but in literary evaluation, it seems inferior.[28] The story of Maṇimēkalai with all its superficial elements seems to be of lesser interest to the author whose aim was pointed toward spreading Buddhism.[28] In the former, ethics and religious are artistic, while in the latter reverse is the case. Maṇimēkalai criticizes Jainism while preaching the ideals of Buddhism, and human interest is diluted in supernatural features. The narration in akaval meter moves on in Maṇimēkalai without the relief of any lyric, which are the main features of Cilappatikāram.[29] Maṇimēkalai in puritan terms is not an epic poem, but a grave disquisition on philosophy.[30]

There are effusions in Cilappatikāram in the form of a song or a dance, which does not go well with the Western audience as they are assessed to be inspired on the spur of the moment.[31] According to Calcutta review, the three works on a whole have no plot and no characterization for an epic genre.[30] The plot of Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi is monotonous and deficient in variety in strength and character and does not stand the quality of an epic.[30]

Popular culture

There have been multiple movies based on Silappathikaram. The most famous is the portrayal of Kannagi by actress Kannamba in the 1942 Tamil movie Kannagi with P.U. Chinnappa playing the lead as Kovalan. The movie faithfully follows the story of Silappathikaram and was a hit when it was released. The movie Poompuhar, penned by M. Karunanidhi, is also based on Silapathikaram.[32] There are multiple dance dramas as well by some of the exponents of Bharatanatyam (a South Indian dance form) in Tamil as most of the verses of Silappathikaram can be set to music.

Maṇimēkalai has been shot as a teleserial in Doordarshan.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Mukherjee 1999, p. 277

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, p. 73

- ↑ M.S. 1994, p. 115

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Das 2005, p.80

- 1 2 Datta 2004, p. 720

- 1 2 3 Zvelebil 1974, p. 130

- 1 2 M.S. 1904, p. 69

- ↑ Zvelebil 1974, p. 131

- 1 2 Pollock 2003, p. 295

- ↑ M.S. 1904, p. 68

- ↑ Rosen, Elizabeth S. (1975). "Prince ILango Adigal, Shilappadikaram (The anklet Bracelet), translated by Alain Damelou. Review". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 148–150. doi:10.2307/3250226. JSTOR 3250226.

- 1 2 Datta 2005, pp. 1194–1196

- 1 2 3 Garg 1992, p. 65

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lal 2001, pp. 4255–4256

- ↑ M.S. 1904, p. 66

- 1 2 M.S. 1904, pp. 72–73

- 1 2 Mukherjee 1999, pp. 150–151

- 1 2 3 4 5 Murthy 1987, p. 102

- 1 2 3 Murthy 1987, p. 103

- 1 2 3 Nadarajah 1994, p. 6

- 1 2 3 4 Nadarajah 1994, p. 310

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 703

- ↑ Pollock 2003, p. 297

- 1 2 3 4 Sen 1988, p. 207

- ↑ Prameshwaranand 2001, p. 1151

- ↑ M.S. 1994, p. 194

- ↑ R. 1993, p. 279

- 1 2 Zvelebil 1974, p. 141

- ↑ Zvelebil 1974, p. 142

- 1 2 3 University of Calcutta 1906, pp. 426–427

- ↑ Paniker 2003, p. 7

- ↑ http://movies.msn.com/movies/movie/kannagi/

References

- Abram, David; Nick Edwards; Mike Ford; Daniel Jacobs; Shafik Meghji; Devdan Sen; Gavin Thomas (2011), The Rough guide to India, Rough Guides, ISBN 978-1-84836-563-6 .

- Aṭikaḷ, Iḷaṅkō. "cilappatikAram of iLangkO atikaL part 1: pukark kANTam" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- Aṭikaḷ, Iḷaṅkō. "cilappatikAram of iLangkO atikaL part 2: maturaik kANTam" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- Aṭikaḷ, Iḷaṅkō. "cilappatikAram of iLangkO atikaL part 3: vanjcik kANTam" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- cAttanAr, cIttalaic. "maNimEkalai" (PDF). projectmadurai.org. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- Das, Sisir Kumar; Sāhitya Akādemī (2005). A history of Indian literature, 500–1399: from courtly to the popular. chennai: Sāhitya Akādemī. ISBN 81-260-2171-3.

- Datta, Amaresh; Sāhitya Akādemī (2004). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume One) (A to Devo), Volume 1. New Delhi: Sāhitya Akādemī.

- Datta, Amaresh; Sāhitya Akādemī (2005). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj To Jyoti), Volume 2. New Delhi: Sāhitya Akādemī. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu world, Volume 1. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-374-1.

- Lal, Mohan; Sāhitya Akādemī (2001). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume Five) (Sasay To Zorgot), Volume 5. New Delhi: Sāhitya Akādemī. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

- Mukherjee, Sujit (1999). A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850. New Delhi: Orient Longman Limited. ISBN 81-250-1453-5.

- Murthy, K. Krishna (1987). Glimpses of art, architecture, and Buddhist literature in ancient India. Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-226-8.

- Nadarajah, Devapoopathy (1994). Love in Sanskrit and Tamil literature: a study of characters and nature, 200 B.C. to 500 A.D. Delhi: Motilal Banaridasss Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 81-208-1215-8.

- Panicker, K. Ayyappa (2003). A Primer of Tamil Literature. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 81-207-2502-6.

- Pillai, M. S. Purnalingam (1904). A Primer of Tamil Literature. Madras: Ananda Press.

- Pillai, M. S. Purnalingam (1994). Tamil Literature. Asian Educational Services. p. 115. ISBN 81-206-0955-7, ISBN 978-81-206-0955-6.

- Pollock, Sheldon I. (2003). Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- R., Parthasarathy (1993). The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal: An Epic of South India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07849-8.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1988). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International(P) Limited Publishers. ISBN 81-224-1198-3.

- Swami Parmeshwaranand (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Purāṇas. Sarup & Sons. p. 1151. ISBN 81-7625-226-3, ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3.

- University of Calcutta (1906), Calcutta review, Volume 123, London: The Edinburgh Press .

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992). Companion studies to the history of Tamil literature. BRILL. p. 73. ISBN 90-04-09365-6, ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1974). A History of Indian literature Vol.10 (Tamil Literature). Otto Harrasowitz. ISBN 3-447-01582-9.