Tang dynasty art

Tang dynasty art (simplified Chinese: 唐朝艺术; traditional Chinese: 唐朝藝術; pinyin: Tángcháo Yìshù; Wade–Giles: T'ang2-ch'ao2 I4-shu4) is Chinese art made during the Tang dynasty (618–907). It is best known for the development of many forms—painting, sculpture, calligraphy, music, dance and literature.

The Tang dynasty, with its capital at Chang'an (today's Xi'an), the most populous city in the world at the time, is regarded by historians as a high point in Chinese civilization—equal, or even superior, to the Han period. The Tang period was considered the golden age of literature and art.

Stimulated by contact with India and the Middle East, the empire saw a flowering of creativity in many fields. Buddhism, originating in what is modern day India around the time of Confucius, continued to flourish during the Tang period and was adopted by the imperial family, becoming thoroughly sinicized and a permanent part of Chinese traditional culture. Block printing made the written word available to vastly greater audiences.

Painting

(1) Buddhist art depicting musicians in paradise, a mural from the Yulin Caves of Dunhuang, Tang dynasty

(2) an armed cortege, mural from the tomb of Li Xian at the Qianling Mausoleum, early 8th century AD

(3) painting on a silk scroll of a female dancer from the Astana Cemetery of Gaochang (Turpan), c. 702 AD

(4) female figure as the planet Venus from the painting "Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Five Planets" (熾盛光佛並五星圖), depicted as playing the pipa, c. 897 AD

Beginning in the Tang dynasty, the primary subject matter of Chinese painting was the landscape, known as shanshui (mountain-water) painting. In these landscapes, usually monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature.

Trading along the Silk Road of various products increased cultural diversity in cosmopolitan Chinese cities, such as Chang'an, had a marked influence on the Chinese arts of the Tang dynasty. Many designs that were enjoyed with the upper classes of imperial China became common even in everyday art.[1]

Pottery

Chinese ceramics saw many significant developments, including the first Chinese porcelain meeting both Western and Chinese definitions of porcelain, in Ding ware and related types. The earthenware Tang dynasty tomb figures are better known in the West today, but were only made to placed in elite tombs close to the capital in the north, between about 680 and 760. They were perhaps the last significant fine earthenwares to be produced in China, many lead-glazed sancai (three-colour) wares, which was also used for vessels for burial, and perhaps for use; the glaze was less toxic than in the Han, but perhaps still to be avoided for use at the dining table. Others are unpainted or were painted over a slip; the paint has now often fallen off.

In the south the wares from the Changsha Tongguan Kiln Site in Tongguan are significant as the first regular use of underglaze painting; examples have been found in many places in the Islamic world. However the production tailed off and underglaze painting remained a minor technique for several centuries.[2]

Yue ware was the leading high-fired, lime-glazed celadon of the period, and was of very sophisticated design, patronized by the court. This was also the case with the northern porcelains of kilns in the provinces of Henan and Hebei, which for the first time met the Western as well as the Eastern definition of porcelain, being a pure white and translucent.[3] One of the first mentions of porcelain by a foreigner was in the Chain of Chronicles written by the Arab traveler and merchant Suleiman in 851 AD during the Tang dynasty who recorded that:[4][5]

| “ | They have in China a very fine clay with which they make vases which are as transparent as glass; water is seen through them. The vases are made of clay. | ” |

The Arabs were well used to glass, and he was certain that the porcelain that he saw was not that.

Yaozhou ware or Northern Celadon also began under the Tang, though like Ding ware its best period was under the next Song dynasty.

Music

The first major well-documented flowering of Chinese music was for the qin during the Tang dynasty, though the qin is known to have been played since before the Han dynasty.

Late 20th century excavations of an intact tomb of the period revealed not only a number of instruments (including a spectacular concert bell set) but also inscribed tablets with playing instructions and musical scores for ensemble concerts, which are now heard again as played on reproduction instruments at the Hubei Provincial Museum.

Opera

Chinese opera is generally dated back to the Tang dynasty with Emperor Xuanzong (712–755), who founded the Pear Garden, the first known opera troupe in China. The troupe mostly performed for the emperors' personal pleasure.

Poetry

The poetry of the Tang dynasty is about the most appreciated poetic era of Chinese poetry. The shi, the classical form of poetry which had developed in the late Han dynasty, reached its zenith.

During the Tang dynasty, poetry became popular, and writing poetry was considered a sign of learning. One of China's greatest poets was Li Po, who wrote about ordinary people and about nature, which was a powerful force in Chinese art. One of Li Po's short poems, "Waterfall at Lu-Shan", shows how Li Po felt about nature.

Tang dynasty artists

- Bai Juyi (772–846), poet

- Zhou Fang (730–800), painter, also known as Zhou Jing Xuan and Zhong Lang

- Cui Hao, poet

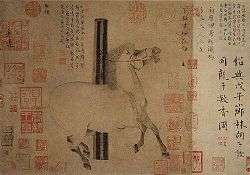

- Han Gan (718–780), painter

- Zhang Xuan (713–755), painter

- Du Fu (712–770), poet

- Li Bai (701–762), poet

- Meng Haoran (689 or 691–740), poet

- Wang Wei (699–759), poet, musician, painter

- Wu Tao-Tzu (680–740), famous for the myth of entering an art work

- Zhang Jiuling (678–740), poet

Gallery

.jpg) Jade-carved dragon, Tang dynasty, Shanghai Museum

Jade-carved dragon, Tang dynasty, Shanghai Museum A rounded ceramic plate with "three colors" glaze and floral design, 8th to 9th century.

A rounded ceramic plate with "three colors" glaze and floral design, 8th to 9th century. A rounded ceramic plate with "three colors" glaze, 8th century.

A rounded ceramic plate with "three colors" glaze, 8th century. A ceramic offering plate with "three colors" glaze, decorated with a bird and trees, 8th century.

A ceramic offering plate with "three colors" glaze, decorated with a bird and trees, 8th century. A ceramic offering plate with six eaves and "three colors" glaze, 8th century.

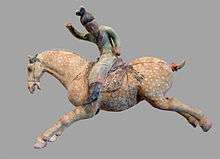

A ceramic offering plate with six eaves and "three colors" glaze, 8th century. Three of eight terracotta lady musicians on horseback, early 8th century

Three of eight terracotta lady musicians on horseback, early 8th century Early T'ang period palace maids, Shensi History Museum

Early T'ang period palace maids, Shensi History Museum Tang court ladies, 706 AD, Qianling Mausoleum

Tang court ladies, 706 AD, Qianling Mausoleum Seated Mahayana Buddha statue

Seated Mahayana Buddha statue Ladies dancing, 7th century

Ladies dancing, 7th century A figurine of a plump Tang woman

A figurine of a plump Tang woman Earthenware statue of a foreigner with a wineskin, c. 674–750

Earthenware statue of a foreigner with a wineskin, c. 674–750 Gilt hexagonal silver plate with a Fei Lian beast pattern

Gilt hexagonal silver plate with a Fei Lian beast pattern A Tang portrait of Emperor Wen of Sui, by Yan Liben, 7th century

A Tang portrait of Emperor Wen of Sui, by Yan Liben, 7th century Buddhist mural in the Bezeklik grottoes, 9th century

Buddhist mural in the Bezeklik grottoes, 9th century ”Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Five Planets”, 897 A.D., British Museum

”Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Five Planets”, 897 A.D., British Museum- Tang dynasty bodhisattva statue missing its head and left arm

- Mirror back with dragon

- Mirror with floral medallion, plant sprays, birds, and insects, 7th century

%2C_Asian_Art_Museum_(6016444483).jpg) Two Guanyin statues

Two Guanyin statues Statue head of Guanyin

Statue head of Guanyin A limestone statue of a mourning attendant, 7th century

A limestone statue of a mourning attendant, 7th century Terracotta lady, 7th-8th century

Terracotta lady, 7th-8th century ”Lokhapala on a Recumbent Bull”, 618-906, Brooklyn Museum

”Lokhapala on a Recumbent Bull”, 618-906, Brooklyn Museum- Tang clay figurine of a Sogdian man wearing a distinctive cap and face veil, possibly a camel rider or even a Zoroastrian priest engaging in a ritual at a fire temple, 8th century AD

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art of the Tang dynasty. |

Notes

- ↑ Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- ↑ Vainker, 82–84

- ↑ Vainker, 64–72

- ↑ Temple, Robert K.G. (2007). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (3rd edition). London: André Deutsch, pp. 103–6. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6

- ↑ Bushell, S. W. (1906). Chinese Art. Victoria and Albert Museum Art Handbook, His Majesty's Stationery Office, London.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7 .

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, OTTO HARRASSOWITZ · WIESBADEN

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300–900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7 .

- Guy, R. Kent (2010), Qing Governors and Their Provinces: The Evolution of Territorial Administration in China, 1644-1796, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295990187

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Perry, John C.; L. Smith, Bardwell (eds.), Essays on T'ang Society: The Interplay of Social, Political and Economic Forces, Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90 04 047611

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-0876-8

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2014), Two Arabic Travel Books, Library of Arabic Literature

- Twitchett, D. (1979), Cambridge History of China, Sui and T'ang China 589–906, Part I, vol.3, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-21446-7

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005), HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PRE-DYNASTIC KHITAN, Institute for Asian and African Studies 7

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7

Further reading

- Vainker, S.J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, 9780714114705

Further reading

- Watt, James C.Y.; et al. (2004). China: dawn of a golden age, 200-750 AD. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391264.