Tašmajdan Park

| Tašmajdan Park | |

|---|---|

| Ташмајдански парк | |

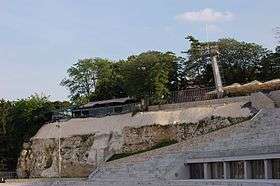

Eastern view of Tašmajdan Park | |

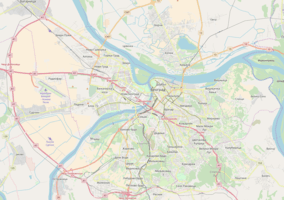

Location within Belgrade | |

| Location | Vračar, Belgrade |

| Coordinates | 44°48.552′N 020°28.246′E / 44.809200°N 20.470767°ECoordinates: 44°48.552′N 020°28.246′E / 44.809200°N 20.470767°E |

| Created | 1958 |

| Open | Open all year |

Tašmajdan Park (Serbian: Ташмајдански парк, translit. Tašmajdanski park), colloquially Tašmajdan or simply just Taš, is a public park and the surrounding urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipality of Vračar. In 2010-2011 the entire park saw its largest reconstruction since its creation in 1954.[1]

Location

Tašmajdan begins 600 m (2,000 ft) southeast of Belgrade's designated center, Terazije, covering the extreme south-west corner of the Palilula municipality, bordering the municipalities of Vračar on the south and Stari Grad on the west. In a narrower sense, Tašmajdan occupies the area bounded by the streets of Takovska on the north-west, Ilije Garašanina on the northeast, Beogradska on the southeast and Bulevar kralja Aleksandra. The majority of the area is occupied by the park itself (central, east, west) while the northern and extreme western sections are urbanised. In wider sense, it occupies the additional area to the north (between Ilije Garašanina and 27. marta streets) and east (between Beogradska and Karnedžijeva streets) The latter is also known as Little Tašmajdan. Tašmajdan is bordered by the neighborhoods of Palilula on the northeast, while it extends into the neighborhoods of Vukov Spomenik, Krunski Venac and Nikola Pašić Square on the east, south and west, respectively.[2][3]

Administration

The neighborhood of Tašmajdan forms a local community (mesna zajednica), sub-municipal administrative unit within Palilula. It had a population of 4,887 in 1981,[4] 4,373 in 1991,[5] 4,018 in 2002,[6] and 3,073 in 2011.[7]

History

Origin

Almost two millennia ago, Romans were extracting stone from the quarry located in the area for the building of Belgrade's predecessor, Singidunum and for many surviving sarcophagi from that period.[8] The quarry remained operational during Ottoman period, thus giving the name to the entire location (Turkish taş, stone and meydan, square),[9] though it was also used for the extraction of saltpeter by Ilija Milosavljević Kolarac,[10] which was used in the gunpowder production. Due to the proximity to the town, basically all stone buildings and walls in Belgrade from Ottoman period were built from the stone extracted here.[11]

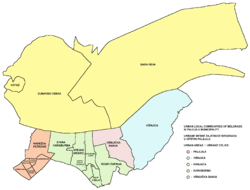

Little Vračar

Some historians believe that this is the actual place where the remains of the Serbian Saint Sava were burned at the stake on 29 April 1595 by the Ottoman grand vizier Sinan Pasha (area known as Little Vračar) and not the Vračar hill itself or Crveni Krst, another alternative site.[12][13] Little Vračar (Serbian: Мали Врачар) occupied the area along the Tsarigrad Road, starting from the modern crossroad of the Takovska Street and Bulevar Kralja Aleksandra.[14] When an international congress of Byzantinologists was held in 1927 in Belgrade, some of them gathered with Marko Kuzmanović, a protopope of the Saint Mark Church. As Kuzmanović wrote, based on previous researches, they all took 60-70 steps from the church altar to the east and ended up on the small mound, called Čupina humka from where both the Sava and the Danube rivers could be seen. Then they told him that this is the exact spot where the remains of Saint Sava were burned. On that spot today is the Šansa restaurant.[15]

Uprisings

During the First Serbian Uprising and the subsequent Siege of Belgrade in autumn of 1806, leader of the Uprising Karađorđe set his camp in Tašmajdan and conducted the liberation of Belgrade from there. A mound in the eastern section of the area was used for public reading of decrees and laws. It was here that on November 30, 1830 the Sultan's hattisherif (decree) was publicly announced, declaring autonomy (de facto, internal independence) of Serbia and granting hereditary ruling rights to the Obrenović dynasty.

Cemetery

After the successful Second Serbian Uprising when Serbian prince Miloš Obrenović ordered the building of a new town around the old Kalemegdan fortress (Savamala neighborhood), he also ordered that the old Serbian cemetery from Varoš Kapija (near Zeleni Venac)[16] be moved to Tašmajdan, which was done in 1828.[9] New cemetery was intended as "international" contrary to the existing practice, so beside Serbs, it was also the burial place for Hungarians, Germans, Greeks, Italians and French.[17] In the western section of the cemetery the Catholics and Protestants were buried, Serbs on the central promenade, while area around modern Seisomology Institute was left for the soldiers, suicides and drowned ones. In 1835 a small Palilulska church was built. Some of the most important Serbs from this period were buried in the churchyard, including politicians Toma Vučić Peršić and Stojan Simić and Stevan Knićanin, philologist Đura Daničić, botanist and first president of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Josif Pančić and philanthropist Ilija Milosavljević Kolarac. Belgraders protested because new cemetery, built on an inhabited fields, gardens and vineyards was away from then downtown, but already in the 1850s, the area surrounding the cemetery was completely urbanised, so the first plans for moving it again originate from 1871. City government bought the cemetery land in 1882 and gradual restriction of burials was conducted until it was closed in fully closed 1901. It was moved to the newly built Belgrade New Cemetery, several blocks to the east, beginning from 1886 and the moving was finally completed in 1927 with park being planted instead of the old cemetery.[18] However, many bodies from older periods were not moved and remained below the park.[14]

Basketball

Tennis court was located on Tašmajdan during World War II. As basketball was played on the clay at the time, local guys began playing basketball there. In 1942-44, a group of 4 players was formed: Bora Stanković (1925), Aleksandar Nikolić (1924-2000), Radomir Šaper (1925-98) and Nebojša Popović (1923-2001). After the war, the group became founding fathers of the "Yugoslav school of basketball".[19] Later, Stanković became secretary general of FIBA, Nikolić was a coach, labeled the "Father of Yugoslav basketball" while Šaper and Popović turned to administrative positions. All four are FIBA Hall of Fame inductees.

Park

The construction of the park began in 1950 and the opening ceremony was held in May 1954.[16][20] The seedlings were transported by the horse wagons from the nursery gardens in Krnjača and from Zagreb's Forestry Faculty.[21]

1999 NATO bombing

Tašmajdan was bombed again during the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia when several objects in Tašmajdan park were badly hit:

- 23 April 1999 - At 2:06 NATO aircraft struck with missiles the building of the Serbian Broadcasting Corporation (RTS) situated in Tašmajdan park. Part of the building collapsed, trapping people who were working in the building that night. Sixteen people were killed while many were trapped for days. The building of the Russian church nearby was also seriously damaged.[22]

- 24 April 1999 - A children’s theatre "Duško Radović" in the heart of Tašmajdan park was badly damaged due to its close proximity to neighbouring buildings that were bombed.

- 30 June 1999 - A heart-like shaped monument was erected by the city of Belgrade for all the children that have died in the bombing. The monument says "We were just children" in English and Serbian.

The bombed RTS building still stands in this condition to date (5 October 2005)

The bombed RTS building still stands in this condition to date (5 October 2005)

New building of RTS also located in Tašmajdan

New building of RTS also located in Tašmajdan Monument to children that have died during the NATO bombing campaign (located in the centre of Tašmajdan park)

Monument to children that have died during the NATO bombing campaign (located in the centre of Tašmajdan park) The theatre which was badly damaged during the bombing—now displaying flags of Europe for the "Joy of Europe" dancing contest

The theatre which was badly damaged during the bombing—now displaying flags of Europe for the "Joy of Europe" dancing contest

2010-2011 reconstruction

In June 2010, it was announced that the park will be completely reconstructed as a gift of Azerbaijan to Belgrade. The park has been reopened in June 2011 after throughout renovation, including the installation of a coloured fountain broadcasting classical music. As a sign of gratitude Belgrade has erected a monument to the former president of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev in the park.[23] Reconstruction included the rebuilding of the paths, removal of sick trees and planting of new ones, construction of two children playgrounds and a special area for the pensioners. Two public toilets and park infrastructure were renovated, the video surveillance system was installed and the statue of the writer Milorad Pavić was erected.[16]

As of 2013, Tašmajdan Park had 1,100 individual trees from 61 different species and covered and area of 11 ha (27 acres).[21]

In November 2017 a complete rearrangement of the plateau, which functioned as an extension of the Tašmajdan Park in front of the St.Mark's Church began. Old asphalt pavement which served as a parking lot was removed. Architect Jovan Mitrović designed a new, leveled combination of granite slabs and green areas. The plateau will be divided in two sections, left and right, divided by the green island. The right, "ceremonial" side will be regularly shaped, with the granite slabs posted in the horizontal rhythm, interrupted with the thin squares of red Italian granite. The design is patterned after the façade of the Michelangelo's temples on Capitoline Hill in Rome. The left side will have "disheveled" pattern, made of differently sized and combined granite slabs..[24] The plateau was finished in February 2018.[25]

In June 2018 it was announced that a monument to Patriarch Pavle, head of the Serbian Orthodox Church from 1990 to 2009, will be erected on the green area between the newly finished plateau and the tram stop in Tašmajdan Park. The bronze monument, authored by Zoran Maleš, will be dedicated on 15 November 2018.[26]

Landmarks

With the surrounding area, Tašmajdan forms the cultural-historical complex Stari Beograd (Old Belgrade), while the park itself is in the zone of the protected natural area of Miocenski sprud-Tašmajdan (Miocene ridge-Tašmajdan).[27]

Churches

Small Palilulska church (church of Palilula) was built in 1835. It was destroyed in the German bombing of Belgrade on April 6, 1941. Today existing Serbian Orthodox St. Mark's Church was built in 1931-1940, in the medieval Serbo-Byzantine style, patterned after the Gračanica monastery. The Serbian Emperor Dušan is buried inside, along with the Serbian Patriarch German. Next to it is a small Russian Orthodox church of the Holy Trinity, built in 1924, inside of which the Russian general Pyotr Wrangel is buried.

Sports complex

Within the Tašmajdan park a sports complex of Tašmajdan Sports Centre is located. Centre administers several facilities located outside Tašmajdan, like "Pionir Hall" and "Ice Hall". However, swimming pools are located in the park. The outdoor swimming pool was built in 1959-1961. Its dimensions are 50 x 20 meters; its depth varies between 2.2 and 5.0 meters; its capacity is 3,500 m³ and 2,500 seats. Next to the big one, there is a small swimming pool for children. Altogether, there is enough room for 4,000 people. It is equipped for international day-and-night competitions in swimming, water polo, water diving, etc. and also used for certain cultural venues or as an outdoor cinema during summer. It was one of the venues for the 2006 Men's European Water Polo Championship and one of the venues of the 2009 Summer Universiade in July 2009, the event for which the pool was renovated. The indoor swimming-pool was built in 1964-1968. Its dimensions are 50 x 20 meters and depth is between 2.2 and 5.4 meters; its capacity is 3,700 m³. The swimming pool is surrounded with four diving boards - 1, 3, 5 and 10 meters high and 2,000 seats. It is equipped with underwater light. At -16 °C, water and air can be heated up to 28 °C.

Some of the best known happenings in the venue include: EuroBasket Women 1954, first Miss Yugoslavia contest in 1957 (won by Tonka Katunarić), 1957 World Women's Handball Championship, concerts of Alexandrov Ensemble in 1958 and later in the 1960s and 1970s of Mazowsze, Ray Charles and Tina Turner and ice hockey matches with over 10,000 spectators.[20]

Seismology Institute

After an earthquake hit Svilajnac in 1893, one of the strongest ever in Serbia, instigated by the geologist Jovan Žujović, the Geology institute of the Great School began collecting data on earthquakes. After the Great School was transformed into the University of Belgrade in 1905, University established the Seismology Institute in 1906 and proposed the location of Tašmajdan. First seismographs were installed in 1909 and the first earthquake was recorded in June 1910. Seismology Institute was officially part of the University of Belgrade until 1995, but is still located in Tašmajdan.[28]

Other

- RTS main building in Takovska and Aberdareva streets. Previously, the television headquarters were located on the Belgrade Fair. After the first phase of the construction was finished, Dnevnik, central daily news, began transmitting from Tašmajdan on 20 July 1967.[29]

- the main post office building of the national post office company Pošta Srbije, built in 1934, in Takovska street.

- The University of Belgrade's Law School, in Bulevar kralja Aleksandra.

- famed Belgrade "Madera" restaurant.

- Hotel "Taš".

- Metropol Hotel Belgrade, in Bulevar kralja Aleksandra.

- statue of Desanka Maksimović, leading Serbian poetess, erected in 2007.

- statue of Milorad Pavić, Serbian writer, author of the Dictionary of the Khazars, erected in 2011.

- children's amusement park.

- many rock pigeons can be seen in the park, popular among the birdwatchers.

- roundabout of the tram line number 6.

Little Tašmajdan

Little Tašmajdan (Serbian: Мали Ташмајдан / Mali Tašmajdan) is the eastern extension of the park, across Beogradska street which forms its western border, while Ilije Garašanina and Karnedžijeva streets form its northern and eastern borders, respectively. The southern section of the complex is the location of the Law Faculty and Hotel Metropol.

The park has recently undergone a renovation. Concrete walkways have been placed (6,000 square metres), and new stairways lighting have been installed. In the centre of the park a playing area for children has been constructed. Near the children’s area there is a fountain which has also been renovated and 30 new benches have been placed in the park as well.

Underworld

Geologically, caves under Tašmajdan are 6 to 8 million years old.[12][13] Remains of the Roman aqueduct are found in the caves. Military arsenals and warehouses have been housed for a long time in the catacombs left after the excavations of stone blocks, and these catacombs have been also used as shelters and first-aid places for wounded soldiers.

During the Interbellum, the Šonda family, which owned the chocolate factory, founded the "ice factory" in Tašmajdan's underground, below the modern building of Radio Television Serbia. The ice was advertised as the "ice from the tap water", as opposed to the naturally occurring ice from the Danube.[30]

It was a major hiding place for the local population during the bombing of Belgrade by the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I. During World War II, the caves were the headquarters of Alexander Löhr, head of the German Air forces in Serbia, and colloquially called "Löhr’s cave".[10] Headquarters were massive, with large metal doors, truck entrances and fully prepared to support 1,000 soldiers for six months without making any surface contact.[8] It could survive chemical and biological attacks, had a ventilation system, power generator, phone lines and elevator and one of the caves was even adapted into the brig for disobedient soldiers.[10] It was also used by the Germans as the collection center for the Jews.[16] Vast labyrinth of corridors, expanded by the Wehrmacht, branches into all directions beneath the city and today nobody knows how many of them there are or where they all lead. Future examinations are slowed because of the lack of funding and many remaining German mines. After 1945 the entrances into the caves were closed and new generations completely lost any knowledge of it. It was only in the 2000s that they were rediscovered and today are slowly turning into one of Belgrade tourist attractions. Occasionally, people illegally dig through the walls of the caves, hoping to find some long lost treasure.[10]

Third large natural cave is right beneath the famed "Šansa" restaurant. It was described by Felix Kanitz, who travelled through Serbia from 1860 to 1864. He noted that in this cave he has found 150 oxcarts with food and that the entire cave could accommodate some 600 carts all together. After World War II, caves were used as “ice factory”, which supplied with ice city kafanas. A big boulder broke off in 1966, fell into the center of the cave and a little girl fell through the hole and got killed. When sports center was built, rubble and remaining bones from the old cemetery were thrown into the caves, with deposits being some 15 meters high today. Old doctors used to say that from these piles they took bones for the anatomy classes.[10]

Aquarium

Underwater research company "Viridijan" announced in June 2006 it would begin construction of the first Belgrade's aquarium in the underground caves beneath Tašmajdan.[31] The project includes construction of 50 underground aquariums with about 1,000 cubic meters of water in the period of 9 years. Over 900 marine animals were supposed to be placed in the natural environment provided by the caves. The project was initially backed by the Ministry of trade in the Government of Serbia and Belgrade City Assembly (the only problem appeared to be the building permit), but the project, which was promised to be "more than just exhibit space" and announcing "the return of Pannonian Sea to Belgrade" was abandoned.[10]

References

- ↑ Roberts, Michael. "Počela rekonstrukcija parka Tašmajdan u centru Beograda". Počela rekonstrukcija parka Tašmajdan u centru Beograda. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ↑ Beograd-plan grada (in Serbian). Smedrevska Palanka: M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- ↑ Tamara Marinković-Radošević (2007). Beograd-plan i vodič (in Serbian). Belgrade: Geokarta. ISBN 978-86-459-0297-2.

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Stanovništvo po opštinama i mesnim zajednicama, Popis 2011. Grad Beograd – Sektor statistike (xls file). 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Tajne Beograda "Secrets of Belgrade"" (in Serbian). 8 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- 1 2 "Tašmajdan-kamenolom "Tašmajdan-quarry"" (in Serbian). 5 October 2004. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Branka Vasiljević (12 June 2016). "Tašmajdanska pećina – buduća turistička atrakcija prestonice" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ↑ Sreten L. Popović (1884). Putovanja po Novoj Srbiji 1878-1880 (in Serbian). Novi Sad.

- 1 2 "Pozdrav ispod Beograda "Greetings from beneath Belgrade" (in Serbian). 2008-07-21. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- 1 2 "Sve tajne beogradskog podzemlja "All secrets of the Belgrade underworld" (in Serbian). 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- 1 2 Nada Kovačević (2014), "Beograd ispod Beograda" [Belgrad beneath Belgrade], Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Dragan Vlahović, "Istorija - mit i zablude: Za dušu Svetog Save" [History - myth and misconceptions: for the soul of Saint Sava], Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 3 4 Branka Vasiljević (November 2010), "Tašmajdan se sprema za veliku obnovu", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Beograd leži na grobljima "Belgrade built on cemeteries"" (in Serbian). 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (23 April 2017), "Šetnja pijacama i parkovima", Politika-Magazin No 1021 (in Serbian), pp. 28–29

- ↑ Aleksandar Miletić (19 November 2017), "Košarkaški vremeplov: od igre do klubizma, part I - Amateri voze "mercedes"" [Basketball chronicles: from game to clubism, part I - Amateurs drive "Mercedes"], Politika (in Serbian), p. 21

- 1 2 Vladimir Stanimirović (4 May 2009), "Podrška za Tašmajdan", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Branka Vasiljević (23 June 2013), "Prestonički parkovi - mladići od šezdeset leta", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ ПОВРЕЖЕДНИЕ СВЯТО-ТРОИЦКОГО ХРАМА В БЕЛГРАДЕ ВЫЗЫВАЕТ СЕРЬЕЗНУЮ ОЗАБОЧЕННОСТЬ РУССКОЙ ПРАВОСЛАВНОЙ ЦЕРКВИ Interfax, 23 April 1999.

- ↑ U znak zahvalnosti dobijaju bistu svog prvog predsednika

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić, Daliborka Mučibabić (28 November 2017), "Novi plato ispred Crkve Svetog Marka" [New plateau in front of the Saint Mark's Church], Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ J.S.T. (17 February 2018). "Plato ispred Crkve Svetog Marka nova oaza u centru grada" [Plateau in front of the St.Mark's Church is a new oasis in downtown]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić, Daliborka Mučibabić (28 June 2018). "Patrijarhu Pavlu spomenik kod Markove crkve" [Monument to Patriarch Pavle near the Mark’s church]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 01.

- ↑ Sekretarijat za komunalne i stambene poslove (8 July 2008), "Planirano uređenje Tašmajdanskog parka", Politika (in Serbian), p. 10

- ↑ "Da li znate? - Gde je izgrađen prvi seizmološki zavod u Srbiji?", Politika (in Serbian), p. 30, 20 May 2017

- ↑ Biserka Matić (20 July 1967), "Poslednji TV dnevnik sa Sajmišta", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Dragan Perić (16 June 2017), "I led može da se ubajati", Politika-Magazin, No. 1033 (in Serbian), p. 28

- ↑ "Company "Viridijan" intends to start construction of first big sea aquarium in caves beneath Tašmajdan park". 2006-05-08. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tašmajdan. |