Tokugawa Ieyasu

| Tokugawa Ieyasu | |

|---|---|

| 徳川家康 | |

|

| |

| Shōgun | |

|

In office 1603–1605 | |

| Monarch | Go-Yōzei |

| Preceded by | Sengoku period |

| Succeeded by | Tokugawa Hidetada |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Matsudaira Takechiyo (松平 竹千代) January 31, 1543 Okazaki Castle, Mikawa (now Okazaki, Japan) |

| Died |

June 1, 1616 (aged 73) Sunpu, Tokugawa shogunate (now Shizuoka, Japan) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

Legitimate:

Illegitimate:

Among others... |

| Mother | Odai-no-kata |

| Father | Matsudaira Hirotada |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | see below |

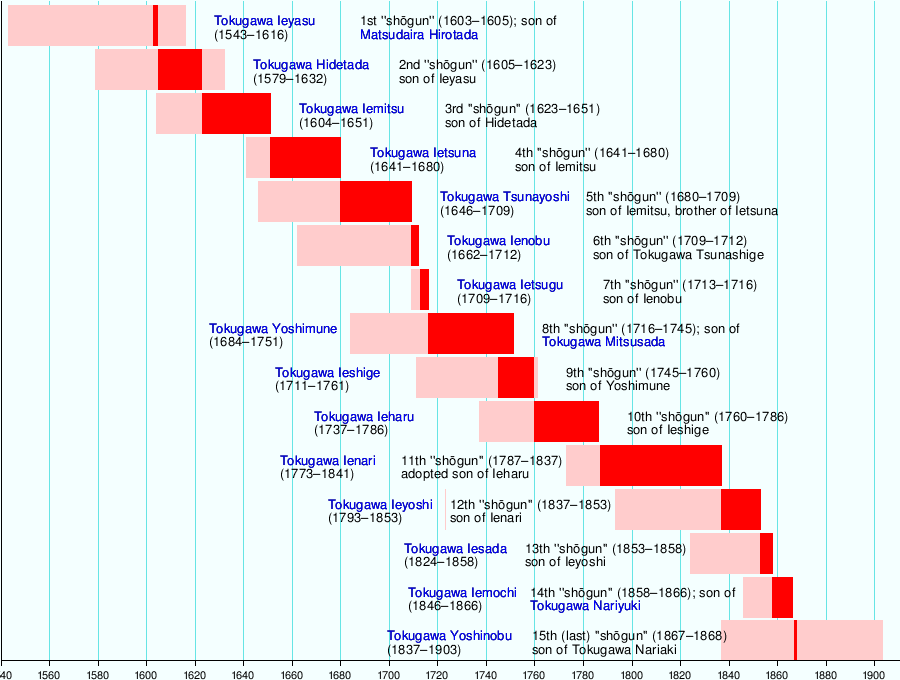

Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川 家康, January 31, 1543 – June 1, 1616) was the founder and first shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, which effectively ruled Japan from the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Ieyasu seized power in 1600, received appointment as shōgun in 1603, and abdicated from office in 1605, but remained in power until his death in 1616. His given name is sometimes spelled Iyeyasu,[1][2] according to the historical pronunciation of the kana character he. Ieyasu was posthumously enshrined at Nikkō Tōshō-gū with the name Tōshō Daigongen (東照大権現). He was one of the three unifiers of Japan, along with his former lord Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Background

During the Muromachi period, the Matsudaira clan controlled a portion of Mikawa Province (the eastern half of modern Aichi Prefecture). Ieyasu's father, Matsudaira Hirotada, was a minor local warlord based at Okazaki Castle who controlled a portion of the Tōkaidō highway linking Kyoto with the eastern provinces. His territory was sandwiched between stronger and predatory neighbors, including the Imagawa clan based in Suruga Province to the east and the Oda clan to the west. Hirotada's main enemy was Oda Nobuhide, the father of Oda Nobunaga.[3]

Early life (1542–1556)

Tokugawa Ieyasu was born in Okazaki Castle on the 26th day of the twelfth month of the eleventh year of Tenbun, according to the Japanese calendar. Originally named Matsudaira Takechiyo (松平 竹千代), he was the son of Matsudaira Hirotada (松平 広忠), the daimyō of Mikawa of the Matsudaira clan, and Odai-no-kata (於大の方, Lady Odai), the daughter of a neighbouring samurai lord, Mizuno Tadamasa (水野 忠政). His mother and father were step-siblings. They were just 17 and 15 years old, respectively, when Ieyasu was born.

In the year of Ieyasu's birth, the Matsudaira clan was split. In 1543, Hirotada's uncle, Matsudaira Nobutaka defected to the Oda clan. This gave Oda Nobuhide the confidence to attack Okazaki. Soon afterwards, Hirotada's father-in-law died, and his son Mizuno Nobumoto revived the clan's traditional enmity against the Matsudaira and declared for Oda Nobuhide as well. As a result, Hirotada divorced Odai-no-kata and sent her back to her family.[3] As both husband and wife remarried and both went on to have further children, Ieyasu eventually had 11 half-brothers and sisters.

As Oda Nobuhide continued to attack Okazaki, in 1548 Hirotada turned to his powerful eastern neighbor, Imagawa Yoshimoto for assistance. Yoshimoto agreed to an alliance under the condition that Hirotada send his young heir to Sunpu Domain as a hostage.[3]

Oda Nobuhide, learned of this arrangement and had Ieyasu abducted from his entourage en route to Sunpu.[4] Ieyasu was just five years old at the time.[5]

Nobuhide threatened to execute Ieyasu unless his father severed all ties with the Imagawa clan; however, Hirotada refused, stating that sacrificing his own son would show his seriousness in his pact with the Imagawa. Despite this refusal, Nobuhide chose not to kill Ieyasu, but instead held him as a hostage for the next three years at the Mansho-ji Temple in Nagoya.

In 1549, when Ieyasu was 6,[5] his father Hirotada was murdered by his own vassals, who had been bribed by the Oda clan. At about the same time, Oda Nobuhide died during an epidemic. Nobuhide's death dealt a heavy blow to the Oda clan. An army under the command of Imagawa Sessai laid siege to the castle where Oda Nobuhiro, Nobuhide's eldest son and the new head of the Oda, was living. With the castle about to fall, Sessai offered a deal to Oda Nobunaga, Nobuhide's second son. Sessai offered to give up the siege if Ieyasu was handed over to the Imagawa. Nobunaga agreed, and so Ieyasu (now nine) was taken as a hostage to Sumpu. At Sumpu, he remained a hostage, but was treated fairly well as a potentially useful future ally of the Imagawa clan until 1556 when he was 15 years old.[5]

Rise to power (1556–1584)

In 1556 Ieyasu officially came of age, with Imagawa Yoshimoto presiding over his genpuku ceremony. Following tradition, he changed his name from Matsudaira Takechiyo to Matsudaira Jirōsaburō Motonobu (松平 次郎三郎 元信). He was also briefly allowed to visit Okazaki to pay his respects to the tomb of his father, and receive the homage of his nominal retainers, led by the karō Torii Tadayoshi.[3]

One year later, at the age of 13 (according to East Asian age reckoning), he married his first wife, Lady Tsukiyama, a relative of Imagawa Yoshitmoto, and changed his name again to Matsudaira Kurandonosuke Motoyasu (松平 蔵人佐 元康). Allowed to return to his native Mikawa, the Imagawa then ordered him to fight the Oda clan in a series of battles.

Motoyasu fought his first battle in 1558 at the Siege of Terabe. The castellan of Terabe in western Mikawa, Suzuki Shigeteru, betrayed the Imagawa by defecting to Oda Nobunaga. This was nominally within Matsudaira territory, so Imagawa Yoshimoto entrusted the campaign to Ieyasu and his retainers from Okazaki. Ieyasu led the attack in person, but after taking the outer defences, grew fearful of a counterattack to the rear, so he burned the main castle and withdrew. As anticipated, the Oda forces attacked his rear lines, but Motoyasu was prepared and drove off the Oda army.[6]

He then succeeded in delivering supplies in the 1559 Siege of Odaka. Odaka was the only one of five disputed frontier forts under attack by the Oda which remained in Imagawa hands. Motoyasu launched diversionary attacks against the two neighboring forts, and when the garrisons of the other forts went to their assistance, Ieyasu’s supply column was able to reach Odaka.[7]

By 1560 the leadership of the Oda clan had passed to the brilliant leader Oda Nobunaga. Imagawa Yoshimoto, leading a large army (perhaps 25,000 strong) invaded Oda clan territory. Motoyasu was assigned a separate mission to capture the stronghold of Marune. As a result, he and his men were not present at the Battle of Okehazama where Yoshimoto was killed in Nobunaga's surprise assault.[4]:37

Alliance with Oda

With Yoshimoto dead, and the Imagawa clan in a state of confusion, Motoyasu used the opportunity to assert his independence and marched his men back into the abandoned Okazaki Castle and reclaimed his ancestral seat.[6]

Motoyasu then decided to ally with the Oda clan.[8] A secret deal was needed because Motoyasu's wife, Lady Tsukiyama, and infant son, Nobuyasu, were held hostage in Sumpu by Imagawa Ujizane, Yoshimoto’s heir.

In 1561, Motoyasu openly broke with the Imagawa and captured the fortress of Kaminogō. Kaminogō was held by Udono Nagamochi. Resorting to stealth, Motoyasu attacked under cover of darkness, setting fire to the castle, and capturing two of Udono’s sons, whom he used as hostages to exchange for his wife and son.[7]:216

In 1563 Nobuyasu was married to Nobunaga's daughter Tokuhime.

For the next few years Motoyasu was occupied with reforming the Matsudaira clan and pacifying Mikawa. He also strengthened his key vassals by awarding them land and castles. These vassals included: Honda Tadakatsu, Ishikawa Kazumasa, Kōriki Kiyonaga, Hattori Hanzō, Sakai Tadatsugu, and Sakakibara Yasumasa.

During this period, the Matsudaira clan also faced a threat from a different source. Mikawa was a major center for the Ikkō-ikki movement, where peasants banded together with militant monks under the Jōdo Shinshū sect, and rejected the traditional feudal social order. Motoyasu undertook several battles to suppress this movement in his territories, including the Battle of Azukizaka.[7]:216 Ts. In one engagement, he was nearly killed when struck by two bullets which did not penetrate his armour. Both sides were using the new gunpowder weapons which the Portuguese had introduced to Japan just 20 years earlier.

Growing Political Influence

In 1567, he changed his name yet again, this time to Tokugawa Ieyasu. By so doing, he claimed descent from the Minamoto clan. No proof has actually been found for this alleged descent from Emperor Seiwa.[9] Yet, his family name was changed with the permission of the Imperial Court, after writing a petition, and he was bestowed the courtesy title Mikawa-no-kami and the court rank of Junior 5th Rank, Lower Grade (従五位下). Ieyasu remained an ally of Nobunaga and his Mikawa soldiers were part of Nobunaga's army which captured Kyoto in 1568. At the same time Ieyasu was expanding his own territory. Ieyasu and Takeda Shingen, the head of the Takeda clan in Kai Province made an alliance for the purpose of conquering all the Imagawa territory.[10]:279 In 1570, Ieyasu's troops captured Yoshida Castle (modern Toyohashi), which made him master of all of Mikawa Province, and he penetrated into Tōtōmi Province. Meanwhile, Shingen's troops captured Suruga Province (including the Imagawa capital of Sunpu). Imagawa Ujizane fled to Kakegawa Castle, which Ieyasu placed under siege. Ieyasu then negotiated with Ujizane, promising that if he should surrender himself and the remainder of Tōtōmi, he would assist Ujizane in regaining Suruga. Ujizane had nothing left to lose, and Ieyasu immediately ended his alliance with Takeda, instead making a new alliance with Takeda’s enemy to the north, Uesugi Kenshin of the Uesugi clan. Through these political manipulations, Ieyasu gained the support of the samurai of Tōtōmi Province.[6]

In 1570, Ieyasu established Hamamatsu as the capital of his territory, placing his son Nobuyasu in charge of Okazaki.[11]

The same year, he led 5,000 of his men to support Nobunaga at the Battle of Anegawa against the Azai and Asakura clans.[4]:62

Conflict with Takeda

In October 1571, Takeda Shingen, now allied with the Odawara Hōjō clan, attacked the Tokugawa lands in Tōtōmi. Ieyasu asked for help from Nobunaga, who sent him some 3,000 troops. Early in 1572 the two armies met at the Battle of Mikatagahara. The considerably larger Takeda army, under the expert direction of Shingen, overwhelmed Ieyasu's troops and caused heavy casualties. Despite his initial reticence, Ieyasu was convinced by one of his generals to retreat.[12][11] The battle was a major defeat, but in the interests of maintaining the appearance of dignified withdrawal, Ieyasu brazenly ordered the men at his castle to light torches, sound drums, and leave the gates open, to properly receive the returning warriors. To the surprise and relief of the Tokugawa army, this spectacle made the Takeda generals suspicious of being led into a trap, so they did not besiege the castle and instead made camp for the night.[12] This error would allow a band of Tokugawa ninja to raid the camp in the ensuing hours, further upsetting the already disoriented Takeda army, and ultimately resulting in Shingen's decision to call off the offensive altogether. Incidentally, Takeda Shingen would not get another chance to advance on Hamamatsu, much less Kyoto, since he would perish shortly after the Siege of Noda Castle a year later in 1573.[8]:153–156

Shingen was succeeded by his less capable son Takeda Katsuyori. In 1575, the Takeda attacked Nagashino Castle in Mikawa Province. Ieyasu appealed to Nobunaga for help and the result was that Nobunaga personally came at the head of a very large army (about 30,000 strong). The Oda-Tokugawa force of 38,000 won a great victory on June 28, 1575, at the Battle of Nagashino, though Takeda Katsuyori survived the battle and retreated back to Kai Province.

For the next seven years, Ieyasu and Katsuyori fought a series of small battles, as the result of which Ieyasu's troops managed to wrest control of Suruga Province away from the Takeda clan.

In 1579, Ieyasu's wife, and his heir Nobuyasu, were accused by Nobunaga of conspiring with Takeda Katsuyori to assassinate Nobunaga, whose daughter Tokuhime (1559–1636) was married to Nobuyasu. For this Ieyasu ordered his wife to be executed and forced his oldest son by her, Nobuyasu, to commit seppuku. Ieyasu then named his third son, Tokugawa Hidetada, as heir, since his second son was adopted by another rising power: the trusted Oda clan general Toyotomi Hideyoshi, soon to be the most powerful daimyō in Japan.

The end of the war with Takeda came in 1582 when a combined Oda-Tokugawa force attacked and conquered Kai Province. Takeda Katsuyori was defeated at the Battle of Tenmokuzan and then committed seppuku.[7]:231

Death of Nobunaga

In late June 1582, Ieyasu was near Osaka and far from his own territory when he learned that Nobunaga had been assassinated by Akechi Mitsuhide. Ieyasu managed the dangerous journey back to Mikawa. Ieyasu was mobilizing his army when he learned Hideyoshi had defeated Akechi Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki.[10]:314-315

The death of Nobunaga meant that some provinces, ruled by Nobunaga's vassals, were ripe for conquest. The leader of Kai province made the mistake of killing one of Ieyasu's aides. Ieyasu promptly invaded Kai and took control. Hōjō Ujimasa, leader of the Hōjō clan responded by sending his much larger army into Shinano and then into Kai Province. No battles were fought between Ieyasu's forces and the large Hōjō army and, after some negotiation, Ieyasu and the Hōjō agreed to a settlement which left Ieyasu in control of both Kai and Shinano Provinces, while the Hōjō took control of Kazusa Province (as well as bits of both Kai and Shinano Provinces).

At the same time (1583) a war for rule over Japan was fought between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Shibata Katsuie. Ieyasu did not take a side in this conflict, building on his reputation for both caution and wisdom. Hideyoshi defeated Katsuie at Battle of Shizugatake. With this victory, Hideyoshi became the single most powerful daimyō in Japan.[10]:314

Ieyasu and Hideyoshi (1584–1598)

In 1584, Ieyasu decided to support Oda Nobukatsu, the eldest surviving son and heir of Oda Nobunaga, against Hideyoshi. This was a dangerous act and could have resulted in the annihilation of the Tokugawa.

Tokugawa troops took the traditional Oda stronghold of Owari; Hideyoshi responded by sending an army into Owari. The Komaki Campaign was the only time any of the great unifiers of Japan fought each other. The campaign proved indecisive and after months of fruitless marches and feints, Hideyoshi settled the war through negotiation. First he made peace with Oda Nobukatsu, and then he offered a truce to Ieyasu. The deal was made at the end of the year; as part of the terms Ieyasu's second son, Ogimaru (also known as Yuki Hideyasu) became an adopted son of Hideyoshi.

Ieyasu's aide, Ishikawa Kazumasa, chose to join the pre-eminent daimyō and so he moved to Osaka to be with Hideyoshi. However, few other Tokugawa retainers followed this example.

Hideyoshi was understandably distrustful of Ieyasu, and five years passed before they fought as allies. The Tokugawa did not participate in Hideyoshi's successful invasions of Shikoku and Kyūshū.

In 1590, Hideyoshi attacked the last independent daimyō in Japan, Hōjō Ujimasa. The Hōjō clan ruled the eight provinces of the Kantō region in eastern Japan. Hideyoshi ordered them to submit to his authority and they refused. Ieyasu, though a friend and occasional ally of Ujimasa, joined his large force of 30,000 samurai with Hideyoshi's enormous army of some 160,000. Hideyoshi attacked several castles on the borders of the Hōjō clan with most of his army laying siege to the castle at Odawara. Hideyoshi's army captured Odawara after six months (oddly for the time period, deaths on both sides were few). During this siege, Hideyoshi offered Ieyasu a radical deal. He offered Ieyasu the eight Kantō provinces which they were about to take from the Hōjō in return for the five provinces that Ieyasu currently controlled (including Ieyasu's home province of Mikawa). Ieyasu accepted this proposal. Bowing to the overwhelming power of the Toyotomi army, the Hōjō accepted defeat, the top Hōjō leaders killed themselves and Ieyasu marched in and took control of their provinces, so ending the clan's reign of over 100 years.

Ieyasu now gave up control of his five provinces (Mikawa, Tōtōmi, Suruga, Shinano, and Kai) and moved all his soldiers and vassals to the Kantō region. He himself occupied the castle town of Edo in Kantō. This was possibly the riskiest move Ieyasu ever made—to leave his home province and rely on the uncertain loyalty of the formerly Hōjō samurai in Kantō. In the end, it worked out brilliantly for Ieyasu. He reformed the Kantō provinces, controlled and pacified the Hōjō samurai and improved the underlying economic infrastructure of the lands. Also, because Kantō was somewhat isolated from the rest of Japan, Ieyasu was able to maintain a unique level of autonomy from Hideyoshi's rule. Within a few years, Ieyasu had become the second most powerful daimyō in Japan. There is a Japanese proverb which likely refers to this event: "Ieyasu won the Empire by retreating."[13]

In 1592, Hideyoshi invaded Korea as a prelude to his plan to attack China. The Tokugawa samurai never actually took part in this campaign, though in early 1593, Ieyasu himself was summoned to Hideyoshi's court in Nagoya (in Kyūshū, different from the similarly spelled city in Owari Province) as a military advisor and given command of a body of troops meant as reserves for the Korean campaign. He stayed in Nagoya off and on for the next five years.[10] Despite his frequent absences, Ieyasu's sons, loyal retainers and vassals were able to control and improve Edo and the other new Tokugawa lands.

In 1593, Hideyoshi fathered a son and heir, Toyotomi Hideyori.

In 1598, with his health clearly failing, Hideyoshi called a meeting that would determine the Council of Five Elders, who would be responsible for ruling on behalf of his son after his death. The five that were chosen as regents (tairō) for Hideyori were Maeda Toshiie, Mōri Terumoto, Ukita Hideie, Uesugi Kagekatsu, and Ieyasu himself, who was the most powerful of the five. This change in the pre-Sekigahara power structure became pivotal as Ieyasu turned his attention towards Kansai; and at the same time, other ambitious (albeit ultimately unrealized) plans, such as the Tokugawa initiative establishing official relations with Mexico (New Spain at the time), continued to unfold and advance.[14][15]

The Sekigahara Campaign (1598–1603)

Hideyoshi, after three more months of increasing sickness, died on September 18, 1598. He was nominally succeeded by his young son Hideyori but as he was just five years old, real power was in the hands of the regents. Over the next two years Ieyasu made alliances with various daimyōs, especially those who had no love for Hideyoshi. Happily for Ieyasu, the oldest and most respected of the regents, Toshiie Maeda, died after just one year. With the death of Toshiie in 1599, Ieyasu led an army to Fushimi and took over Osaka Castle, the residence of Hideyori. This angered the three remaining regents and plans were made on all sides for war. It was also the last battle of one of the most loyal and powerful retainers of Ieyasu, Honda Tadakatsu.

Opposition to Ieyasu centered around Ishida Mitsunari, a powerful daimyō who was not one of the regents. Mitsunari plotted Ieyasu's death and news of this plot reached some of Ieyasu's generals. They attempted to kill Mitsunari but he fled and gained protection from none other than Ieyasu himself. It is not clear why Ieyasu protected a powerful enemy from his own men but Ieyasu was a master strategist and he may have concluded that he would be better off with Mitsunari leading the enemy army rather than one of the regents, who would have more legitimacy.[16]

Nearly all of Japan's daimyōs and samurai now split into two factions—The Western Army (Mitsunari's group) and The Eastern Army (anti-Mitsunari Group). Ieyasu supported the anti-Mitsunari Group, and formed them as his potential allies. Ieyasu's allies were the Date clan, the Mogami clan, the Satake clan and the Maeda clan. Mitsunari allied himself with the three other regents: Ukita Hideie, Mōri Terumoto, and Uesugi Kagekatsu as well as many daimyō from the eastern end of Honshū.

In June 1600, Ieyasu and his allies moved their armies to defeat the Uesugi clan, which was accused of planning to revolt against Toyotomi administration. Before arriving at Uesugi's territory, Ieyasu received information that Mitsunari and his allies had moved their army against Ieyasu. Ieyasu held a meeting with the daimyōs, and they agreed to follow Ieyasu. He then led the majority of his army west towards Kyoto. In late summer, Ishida's forces captured Fushimi.

Ieyasu and his allies marched along the Tōkaidō, while his son Hidetada went along the Nakasendō with 38,000 soldiers. A battle against Sanada Masayuki in Shinano Province delayed Hidetada's forces, and they did not arrive in time for the main battle.

This battle, fought near Sekigahara, was the biggest and one of the most important battles in Japanese feudal history. It began on October 21, 1600, with a total of 160,000 men facing each other. The Battle of Sekigahara ended with a complete Tokugawa victory.[17] The Western bloc was crushed and over the next few days Ishida Mitsunari and many other western nobles were captured and killed. Tokugawa Ieyasu was now the de facto ruler of Japan.

Immediately after the victory at Sekigahara, Ieyasu redistributed land to the vassals who had served him. Ieyasu left some western daimyōs unharmed, such as the Shimazu clan, but others were completely destroyed. Toyotomi Hideyori (the son of Hideyoshi) lost most of his territory which were under management of western daimyōs, and he was degraded to an ordinary daimyō, not a ruler of Japan. In later years the vassals who had pledged allegiance to Ieyasu before Sekigahara became known as the fudai daimyō, while those who pledged allegiance to him after the battle (in other words, after his power was unquestioned) were known as tozama daimyō. Tozama daimyō were considered inferior to fudai daimyōs.

Shōgun (1603–1605)

On March 24, 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu received the title of shōgun from Emperor Go-Yōzei.[18] Ieyasu was 60 years old. He had outlasted all the other great men of his times: Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, Shingen, Kenshin. As shōgun, he used his remaining years to create and solidify the Tokugawa shogunate, which ushered in the Edo period, and was the third shogunal government (after the Kamakura (Minamoto) and the Ashikaga). He claimed descent from the Minamoto clan, by way of the Nitta clan. His descendants would marry into the Taira clan and the Fujiwara clan. The Tokugawa shogunate would rule Japan for the next 250 years.

Following a well established Japanese pattern, Ieyasu abdicated his official position as shōgun in 1605. His successor was his son and heir, Tokugawa Hidetada. There may have been several factors that contributed to his decision, including his desire to avoid being tied up in ceremonial duties, to make it harder for his enemies to attack the real power center, and to secure a smoother succession of his son.[19] The abdication of Ieyasu had no effect on the practical extent of his powers or his rule; but Hidetada nevertheless assumed a role as formal head of the shogunal bureaucracy.

Ōgosho (1605–1616)

Ieyasu, acting as the retired shōgun (大御所 ōgosho), remained the effective ruler of Japan until his death. Ieyasu retired to Sunpu Castle in Sunpu, but he also supervised the building of Edo Castle, a massive construction project which lasted for the rest of Ieyasu's life. The result was the largest castle in all of Japan, the costs for building the castle being borne by all the other daimyōs, while Ieyasu reaped all the benefits. The central donjon, or tenshu, burned in the 1657 Meireki fire. Today, the Imperial Palace stands on the site of the castle.

In 1611, Ieyasu, at the head of 50,000 men, visited Kyoto to witness the enthronement of Emperor Go-Mizunoo. In Kyoto, Ieyasu ordered the remodeling of the imperial court and buildings, and forced the remaining western daimyōs to sign an oath of fealty to him.

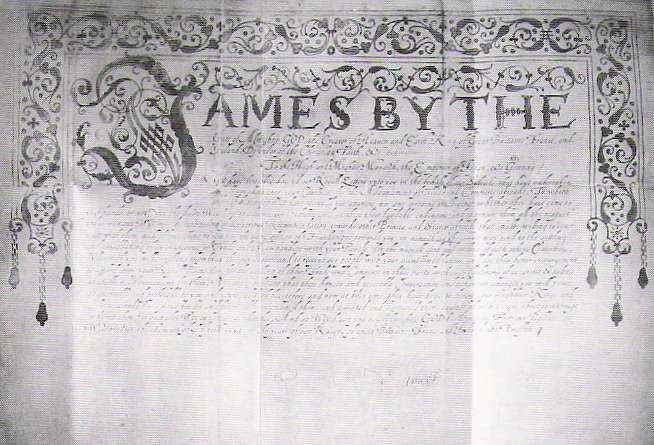

In 1613, he composed the Kuge Shohatto (ja:公家諸法度), a document which put the court daimyōs under strict supervision, leaving them as mere ceremonial figureheads.

In 1615, Ieyasu prepared the Buke shohatto (武家諸法度), a document setting out the future of the Tokugawa regime.

Relations with foreign powers

As Ōgosho, Ieyasu also supervised diplomatic affairs with the Netherlands, Spain and England. Ieyasu chose to distance Japan from European influence starting in 1609, although the shogunate did still grant preferential trading rights to the Dutch East India Company and permitted them to maintain a "factory" for trading purposes.

From 1605 until his death, Ieyasu consulted frequently with English shipwright and pilot, William Adams,[20] Adams, fluent in Japanese, assisted the shogunate in negotiating trading relations, but was cited by members of the competing Jesuit and Spanish-sponsored mendicant orders as an obstacle to improved relations between Ieyasu and the Roman Catholic Church.[21][22][23]

Significant attempts to curtail the influence of Christian missionaries in Japan date to 1587 during the shogunate of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. However, in 1614, Ieyasu was sufficiently concerned about Spanish territorial ambitions that he signed a Christian Expulsion Edict. The edict banned the practice of Christianity and led to the expulsion of all foreign missionaries. Although some smaller Dutch trading operations remained in Nagasaki, this edict dramatically curtailed foreign trade and marked the end of open Christian witness in Japan until the 1870s.[24] The immediate cause of the prohibition was the Okamoto Daihachi incident, a case of fraud involving Ieyasu's Catholic vavasor, but the shogunate was also concerned about a possible invasion by the Iberian colonial powers, which had previously occurred in the New World and the Philippines.

Siege of Osaka

The last remaining threat to Ieyasu's rule was Toyotomi Hideyori, the son and rightful heir to Hideyoshi. He was now a young daimyō living in Osaka Castle. Many samurai who opposed Ieyasu rallied around Hideyori, claiming that he was the rightful ruler of Japan. Ieyasu found fault with the opening ceremony of a temple built by Hideyori; it was as if he prayed for Ieyasu's death and the ruin of the Tokugawa clan. Ieyasu ordered Toyotomi to leave Osaka Castle, but those in the castle refused and summoned samurai to gather within the castle. Then the Tokugawa, with a huge army led by Ieyasu and shōgun Hidetada, laid siege to Osaka castle in what is now known as "the Winter Siege of Osaka". Eventually, Tokugawa was able to precipitate negotiations and an armistice after directed cannon fire threatened Hideyori's mother, Yodo-dono. However, once the treaty was agreed, Tokugawa filled the castle's outer moats with sand so his troops could walk across. Through this ploy, Tokugawa gained a huge tract of land through negotiation and deception that he could not through siege and combat. Ieyasu returned to Sunpu Castle once, but after Toyotomi refused another order to leave Osaka, he and his allied army of 155,000 soldiers attacked Osaka Castle again in "the Summer Siege of Osaka".

Finally, in late 1615, Osaka Castle fell and nearly all the defenders were killed including Hideyori, his mother (Hideyoshi's widow, Yodo-dono), and his infant son. His wife, Senhime (a granddaughter of Ieyasu), pleaded to save Hideyori and Yodo-dono's lives. Ieyasu refused and either required them to commit ritual suicide, or killed both of them. Eventually, Senhime was sent back to Tokugawa alive. After killing two people at Kamakura, who have escaped from Osaka Castle. With the Toyotomi line finally extinguished, no threats remained to the Tokugawa clan's domination of Japan.

Death

In 1616, Ieyasu died at age 73.[5] The cause of death is thought to have been cancer or syphilis. The first Tokugawa shōgun was posthumously deified with the name Tōshō Daigongen (東照大権現), the "Great Gongen, Light of the East". (A Gongen is believed to be a buddha who has appeared on Earth in the shape of a kami to save sentient beings). In life, Ieyasu had expressed the wish to be deified after his death to protect his descendants from evil. His remains were buried at the Gongens' mausoleum at Kunōzan, Kunōzan Tōshō-gū (久能山東照宮). As a common view, many people believe that "after the first anniversary of his death, his remains were reburied at Nikkō Shrine, Nikkō Tōshō-gū (日光東照宮). His remains are still there." Neither shrine has offered to open the graves, so the location of Ieyasu's physical remains are still a mystery. The mausoleum's architectural style became known as gongen-zukuri, that is gongen-style.[25] He was first given the Buddhist name Tosho Dai-Gongen (東照大権現), then after his death it was changed to Hogo Onkokuin (法号安国院).

Era of Ieyasu's rule

Ieyasu ruled directly as shōgun or indirectly as Ōgosho (大御所) during the Keichō era (1596–1615).

Ieyasu's character

Ieyasu had a number of qualities that enabled him to rise to power. He was both careful and bold—at the right times, and in the right places. Calculating and subtle, Ieyasu switched alliances when he thought he would benefit from the change. He allied with the Late Hōjō clan; then he joined Hideyoshi's army of conquest, which destroyed the Hōjō; and he himself took over their lands. In this he was like other daimyōs of his time. This was an era of violence, sudden death, and betrayal. He was not very well liked nor personally popular, but he was feared and he was respected for his leadership and his cunning. For example, he wisely kept his soldiers out of Hideyoshi's campaign in Korea.

He was capable of great loyalty: once he allied with Oda Nobunaga, he never went against him, and both leaders profited from their long alliance. He was known for being loyal towards his personal friends and vassals, whom he rewarded, He was said to have a close friendship with his vassal Hattori Hanzō. However, he also remembered those who had wronged him in the past. It is said that Ieyasu executed a man who came into his power because he had insulted him when Ieyasu was young.

Ieyasu protected many former Takeda retainers from the wrath of Oda Nobunaga, who was known to harbor a bitter grudge towards the Takeda. He managed successfully to transform many of the retainers of the Takeda, Hōjō, and Imagawa clans—all whom he had defeated himself or helped to defeat—into loyal followers. At the same time, he could be ruthless when crossed. For example, he ordered the executions of his first wife and his eldest son—a son-in-law of Oda Nobunaga; Oda was also an uncle of Hidetada's wife Oeyo.[26]

He was cruel, relentless and merciless in the elimination of Toyotomi survivors after Osaka. For days, dozens and dozens of men and women were hunted down and executed, including an eight-year-old son of Hideyori by a concubine, who was beheaded.[27]

Unlike Hideyoshi, he did not harbor any desires to conquer outside Japan—he only wanted to bring order and an end to open warfare, and to rule Japan.[28]

While at first tolerant of Christianity,[29] his attitude changed after 1613 and the executions of Christians sharply increased.[30]

Ieyasu's favorite pastime was falconry. He regarded it as excellent training for a warrior. "When you go into the country hawking, you learn to understand the military spirit and also the hard life of the lower classes. You exercise your muscles and train your limbs. You have any amount of walking and running and become quite indifferent to heat and cold, and so you are little likely to suffer from any illness.".[31] Ieyasu swam often; even late in his life he is reported to have swum in the moat of Edo Castle.

Later in life he took to scholarship and religion, patronizing scholars like Hayashi Razan.[32]

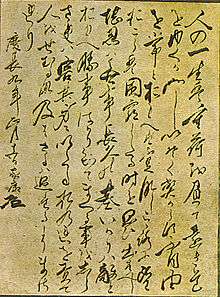

Two of his famous quotes:

Life is like unto a long journey with a heavy burden. Let thy step be slow and steady, that thou stumble not. Persuade thyself that imperfection and inconvenience are the lot of natural mortals, and there will be no room for discontent, neither for despair. When ambitious desires arise in thy heart, recall the days of extremity thou hast passed through. Forbearance is the root of all quietness and assurance forever. Look upon the wrath of thy enemy. If thou only knowest what it is to conquer, and knowest not what it is to be defeated; woe unto thee, it will fare ill with thee. Find fault with thyself rather than with others.[33]

The strong manly ones in life are those who understand the meaning of the word patience. Patience means restraining one's inclinations. There are seven emotions: joy, anger, anxiety, adoration, grief, fear, and hate, and if a man does not give way to these he can be called patient. I am not as strong as I might be, but I have long known and practiced patience. And if my descendants wish to be as I am, they must study patience.[34][35]

He said that he fought, as a warrior or a general, in 90 battles.

He was interested in various kenjutsu skills, was a patron of the Yagyū Shinkage-ryū school, and also had them as his personal sword instructors.

Honours

- Senior First Rank (April 14, 1617; posthumous)

Family

Parents

- Father: Matsudaira Hirotada

- Mother: Odai no Kata (1528–1602), daughter of Mizuno Tadamasa

Siblings

Father Side

- Matsudaira Iemoto

- Naitō Nobunari

- Ichibahime (d. 1593) married Arakawa Yoshihiro

- Matsudaira Chikayoshi

- Yadahime married Matsudaira Yasutada

- Matsudaira Tadamasa (1544–1591)

- Shooko Eike

Mother Side

- Hisamatsu Sadakatsu

- Matsudaira Yasumoto (1552–1603)

- Matsudaira Yasutoshi (1552–1586)

- Take-hime (1553–1618) married Matsudaira Tadamasa later married Matsudaira Tadayoshi later married Hoshina Masanao

Wives and Concubines

He had 2 wives and 19 Concubines

- Wives:

- Concubines:

- Acha no Tsubone

- Saigō-no-Tsubone

- Kageyama-dono (1580–1653) also known as Oman no Kata later Yoju-in

- Lady Oman (1548–1620) later Chosho-in

- Okame no Kata (1573–1642) later Sooin

- Lady Chaa

- Okaji no Kata

- Tomiko (d. 1628) later Shinshuin

- Nishigori no Tsubone (d. 1606) later Hasuin

- Otake no Kata (1555–1637) later Ryoun-in

- Omatsu no Kata later Hokoin

- Otoma no Kata (1564–1591) later Myoshin-in

- Oume no Kata (1586–1647) later Renge'in

- Ohisa no Kata (d. 1617) later Fushoin

- Onatsu no Kata (1581–1660) later Seishunin

- Oroku no Kata (1597–1625) later Yogen'in

- Shimoyama-dono (1567–1591) later Myosin-in

- Osen no Kata (d. 1619) later Taiei-in

- Omusu no Kata (d. 1692) later Seiei-in

Children

He had eleven sons and five daughters :

- Matsudaira Nobuyasu (by his official wife, Lady Tsukiyama)

- Kamehime (by his official wife, Lady Tsukiyama)

- Toku-hime by Nishigori no Tsubone

- Yūki Hideyasu by Lady Oman

- Tokugawa Hidetada by Saigō-no-Tsubone

- Matsudaira Tadayoshi by Saigō-no-Tsubone

- Furi-hime (1580–1617) by Otake, married Gamō Hideyuki later married Asano Nagaakira later known as Shosei-in

- Takeda Nobuyoshi by Otoma

- Matsudaira Tadateru by Lady Chaa

- Matsudaira Matsuchiyo by Lady Chaa

- Matsudaira Senchiyo (1595–1600) by Okame no Kata

- Tokugawa Yoshinao by Okame no Kata

- Tokugawa Yorinobu by Kageyama-dono

- Tokugawa Yorifusa by Kageyama-dono

- Matsuhime (b. 1605) by Ohisa

- Ichi-hime (1607–1610) by Okaji

His daughters were Kame hime (亀姫), Toku hime (督姫), Furi hime (振姫), Matsu hime (松姫) and Ichi hime (市姫). He is said to have cared for his children and grandchildren, establishing three of them, Yorinobu, Yoshinao, and Yorifusa as the daimyōs of Kii, Owari, and Mito Provinces, respectively.[36]

Adopted children

- Matsudaira Ieharu (1579–1592) son of Okudaira Nobumasa

- Matsudaira Tadaaki

- Matsudaira Tadamasa (1580–1614)

- Komatsuhime, daughter of Honda Tadakatsu, married to Sanada Nobuyuki had 2 sons and 1 daughter: Sanada Nobuyoshi of Numata Domain, Sanada Nobumasa of Ueda Domain, Manhime

- Matehime (d. 1638), daughter of Matsudaira Yasumoto, married Tsugaru Nobuhira had 1 son: Tsugaru Nobufusa (1620–1662) of Kuroishi Domain

- Kamehime (1597–1643), daughter of Honda Tadamasa married Ogasawara Tadazane had 2 sons and 1 daughter: Ogasawara Nagayasu, Ogasawara Naganobu, Ichimatsuhime married Kuroda Mitsuyuki

- Ei-hime (1585–1635), daughter of Hoshina Masanao married Kuroda Nagamasa had 3 sons: Kuroda Tadayuki of Fukuoka Domain, Kuroda Nagaoki, Kuroda Takamasa

- Kumahime (1595–1632) daughter of Hisamatsu Sadakatsu married Yamauchi Tadayoshi of Tosa Domain had son: Yamauchi Tadatoyo of Tosa Domain, Yamauchi Tadanao

- Renhime (1582–1652) daughter of Matsudaira Yasunao married Arima Toyouji of Kurume Domain had 2 sons: Arima Yoritsugu and Arima Tadayori of Kurume Domain

- Kunihime (1595–1649) daughter of Honda Tadamasa married Hori Tadatoshi later married Arima Naozumi had a son: Arima Yasuzumi

- Hisatsu-in daughter of Matsudaira Yasumoto married Tanaka Tadamasa later married Matsudaira Narishige

- Jomyo-in daughter of Matsudaira Yasumoto married Nakamura Kazutada later married Mōri Hidemoto

- Toumei-in (d. 1639) daughter of Matsudaira Yasuchika married Ii Naomasa had 1 son: Ii Naokatsu

- Kikuhime (1588–1661) daughter of Okabe Nagamori married Nabeshima Katsushige had 3 sons: Nabeshima Tadanao, Nabeshima Naozumi, Nabeshima Naotomo

- Shojo-in (1582–1656) daughter of Mizuno Tadashige married Katō Kiyomasa

- Teishoin (1591–1664) daughter of Hoshina Masanao married Koide Yoshihide had 2 sons: Koide Yoshishige, Hoshina Masahide

- Shosen'in daughter of Makino Yasunari married Fukushima Masanori

- daughter of Hoshina Masanao married Anbe Nobumori had 1 son: Anbe Nobuyuki

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Tokugawa Ieyasu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ieyasu in popular culture

In James Clavell's historical-novel Shōgun, Tokugawa served as basis for the character of "Toranaga". Toranaga was portrayed by Toshiro Mifune in the 1980 TV mini-series adaptation.

Hyouge Mono (へうげもの Hepburn: Hyōge Mono, lit. "Jocular Fellow") is a Japanese manga written and illustrated by Yoshihiro Yamada. It was adapted into an anime series in 2011, and includes a fictional depiction of Tokugawa's life.

In Sengoku Basara game and anime series, he was shown with Honda Tadakatsu. In earlier games, he was armed with spears and led countless warriors, in latter ones, he discards the spear and fights with his fists and wants Japan united under the force of bonds.

Honnōji theory

Among the many conspiracies surrounding the Honnō-ji Incident is Ieyasu's role in the event. Historically, Ieyasu was away from his lord at the time and, when he heard that Nobunaga was in danger, he wanted to rush to his lord's rescue in spite of the small number of attendants with him. However, Tadakatsu advised for his lord to avoid the risk and urged for a quick retreat to Mikawa. Masanari led the way through Iga and they returned home by boat.

However, skeptics think otherwise. While they usually accept the historically known facts about Ieyasu's actions during Mitsuhide's betrayal, theorists tend to pay more attention to the events before. Ever since Ieyasu lost his wife and son due to Nobunaga's orders, they reason, he held a secret resentment against his lord. Generally, there is some belief that he privately goaded Mitsuhide to take action when the two warlords were together in Azuchi Castle. Together, they planned when to attack and went their separate ways. When the deed was done, Ieyasu turned a blind eye to Mitsuhide's schemes and fled the scene to feign innocence. A variation of the concept states that Ieyasu was well aware of Mitsuhide's feelings regarding Nobunaga and simply chose to do nothing for his own benefit.

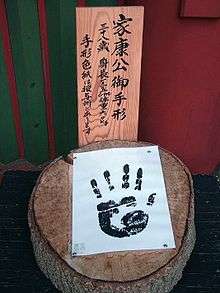

Impostor theory

Tokugawa Ieyasu's Kagemusha Legend (徳川家康の影武者説) is a myth that has been circulating since the Edo period. It is believed to have arisen due to historical records of Ieyasu's "sudden change of behavior" with some of his closest colleagues. The idea was made more popular in modern times by the historians, Tokutomi Sohō and Yasutsugu Shigeno.

The general outline of the legend is that after the Battle of Okehazama, Motoyasu (Ieyasu) was ready to face the world as a changed man. According to Hayashi Razan, the last line was meant quite literally. Before Motoyasu could make his new face known to the world, he was replaced by a completely different man named Sarata Jiro Saburo Motonobu (Sakai Jōkei). Variations include that the switch actually occurred much earlier in Motoyasu's life when he was being a hostage. Motonobu went in Motoyasu's stead and was considered a more suitable "heir". After Motonobu replaced him, Motoyasu fled and lived a hermit's life. Another version states that Ieyasu was actually killed during the Battle of Sekigahara or the Osaka Campaign. When he was killed by Sanada Nobushige during the latter conflict, it is said that he was replaced by Ogasawara Hidemasa who became the "Ieyasu" from then on.

While prevalent in fiction, historians are unsure whether or not the myth holds any merit. His dubious personality traits during these specific time frames have been mostly blamed on stress and personal strain.

Notable descendants

| Extended content |

|---|

Kamehime

Furihime

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Iyeyasu". Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ "Iyeyasu". Merriam-Webster.

- 1 2 3 4 Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Tokugawa Ieyasu. Osprey Publishing. pp. 5–9. ISBN 9781849085748.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull, Stephen (1987). Battles of the Samurai. Arms and Armour Press. p. 35. ISBN 0853688265.

- 1 2 3 4 Screech, Timon (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

ISBN 0-7007-1720-X, pp. 85, 234; n.b., Screech explains

Minamoto-no-Ieyasu was born in Tenbun 11, on the 26th day of the 12th month (1542) and he died in Genna 2, on the 17th day of the 4th month (1616); and thus, his contemporaries would have said that he lived 75 years. In this period, children were considered one year old at birth and became two the following New Year's Day; and all people advanced a year that day, not on their actual birthday.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Tokugawa Ieyasu. Osprey Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 9781849085748.

- 1 2 3 4 Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. Cassell & Co. p. 215. ISBN 1854095234.

- 1 2 Turnbull, Stephen R. (1977). The Samurai: A Military History. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. p. 144.

- ↑ Screech, Timon (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1720-X, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 4 Sansom, Sir George Bailey (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford University Press. p. 353. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

- 1 2 Turnbull, Stephen (1987). Battle of the Samurai. London: Arms and Armour Press. pp. 67–78. ISBN 0853688265.

- 1 2 Turnbull, Stephen (2000). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & C0. pp. 222–223. ISBN 1854095234.

- ↑ Sadler, p. 164.

- ↑ Nutall, Zelia. (1906). The Earliest Historical Relations Between Mexico and Japan, p. 2

- ↑ "Japan to Decorate King Alfonso Today; Emperor's Brother Nears Madrid With Collar of the Chrysanthemum for Spanish King". The New York Times, November 3, 1930, p. 6.

- ↑ Sadler, p. 187

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac (1834). [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō, 1652], Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, p. 405.

- ↑ Titsingh, Isaac (1822). Illustrations of Japan. London: Ackerman, p. 409.

- ↑ Van Wolferen, Karel (1990). The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation. New York: Vintage Books. p. 28. ISBN 0-679-72802-3.

- ↑ Milton, Giles. Samurai William: The Englishman Who Opened Japan. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003.

- ↑ Nutail, Zelia (1906). The Earliest Historical Relations Between Mexico and Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 6–45.

- ↑ Milton, Giles. Samurai William : the Englishman Who Opened Japan. p. 265. Quoting Le P. Valentin Carvalho, S.J.

- ↑ Murdoch, James; Yamagata, Isoh (1903). A History of Japan. Kelly & Walsh. p. 500.

- ↑ Mullins, Mark R. (1990). "Japanese Pentecostalism and the World of the Dead: a Study of Cultural Adaptation in Iesu no Mitama Kyokai". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 17 (4): 353–374.

- ↑ JAANUS / Gongen-zukuri 権現造

- ↑ "Jyoukouji:The silk coloured portrait of wife of Takatsugu Kyogoku". 2011-05-06. Archived from the original on 2011-05-06. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- ↑ Sansom, George, A History of Japan, 1615–1867, Stanford University Press. 1960, p. 9

- ↑ Frederic, Louis, Daily Live in Japan at the Time of the Samurai, 1185–1603, Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., Rutland, Vermont, 1973, p. 180

- ↑ Leonard, Jonathan, Early Japan, Time-Life Books, New York, ç1968, p.162

- ↑ Sansom, G. B., The Western World and Japan, Charles E. Tuttle Company, Rutland and Tokyo, 1950, p. 132

- ↑ Sadler, p. 344.

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1956). Kyoto: the Old Capital of Japan, 794–1969, p. 418.

- ↑ OldTokyo.com: Tōshō-gū Shrine; American Forum for Global Education, JapanProject Archived 2012-12-31 at the Wayback Machine.; retrieved 2012-11-1.

- ↑ Storry, Richard. (1982). A History of Modern Japan, p. 60

- ↑ Thomas, J. E. (1996). Modern Japan: a social history since 1868, ISBN 0582259614, p. 4.

- ↑ On the subject, see the article Gosanke.

- ↑ "Genealogy". Reichsarchiv. Retrieved 17 December 2017. (in Japanese)

Bibliography

- Sadler, A. L. (1937). The Maker of Modern Japan.

Further reading

- Bolitho, Harold (1974). Treasures Among Men: The Fudai Daimyo in Tokugawa Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-01655-0. OCLC 185685588.

- McClain, James (1991). The Cambridge History of Japan Volume 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McLynn, Frank (2008). The Greatest Shogun, BBC History Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp 52–53.

- あおもりの文化財 徳川家康自筆日課念仏 – 青森県庁ホームページ

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

- Totman, Conrad D. (1967). Politics in the Tokugawa Bakufu, 1600–1843. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 279623.

External links

- The Christian Century in Japan, by Charles Boxer

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sengoku period |

Shōgun: Tokugawa Ieyasu 1603–1605 |

Succeeded by Tokugawa Hidetada |