Suicide prevention

Suicide prevention is an umbrella term used for the collective efforts of local citizen organizations, health professionals and related professionals to reduce the incidence of suicide. Beyond direct interventions to stop an impending suicide, methods also involve:

- Treating the psychological and psychophysiological symptoms of depression.

- Improving the coping strategies of persons who would otherwise seriously consider suicide.

- Reducing the prevalence of conditions believed to constitute risk factors for suicide.

- Giving people hope for a better life after current problems are resolved.

General efforts have included preventive and proactive measures within the realms of medicine and mental health, as well as public health and other fields. Because protective factors such as social support and social engagement — as well as environmental risk factors such as access to lethal means — apparently play some significant roles in suicide prevention, suicide should not be viewed solely as neither a medical issue nor a mental health issue.[1][2] Suicide prevention is risky for health professionals in terms of practitioner emotional distress and risk for malpractice suits.[3]

Risk assessment

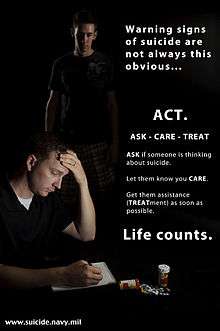

Warning signs

Being aware of the warning signs of suicide can allow individuals to direct people who may be considering suicide to get help.[4]

Warning signs include:[5]

- Suicidal ideation: thinking, talking, or writing about suicide, planning for suicide

- Substance abuse

- Purposelessness

- Anxiety, agitation and unable to sleep or not sleeping all the time

- Trapped

- Hopelessness

- Social withdrawal from friends, family, or society

- Anger, rage or seeking revenge

- Recklessness or impulsiveness

- Mood changes including depression

Additionally, the national institute for mental health includes feeling burdonsome, and strong feelings of pain--either emotional or physical--as warning signs that someone may intend attempt suicide.[4]

Some signs that someone may attempt suicide include:[4]

- strong feelings of pain, either emotional or physical considering oneself burdensome

- increased use of drugs or alcohol

Screening

The U.S. Surgeon General has suggested that screening to detect those at risk of suicide may be one of the most effective means of preventing suicide in children and adolescents.[6] There are various screening tools in the form of self-report questionnaires to help identify those at risk such as the Beck Hopelessness Scale and Is Path Warm?. A number of these self-report questionnaires have been tested and found to be effective for use among adolescents and young adults.[7] There is however a high rate of false-positive identification and those deemed to be at risk should ideally have a follow-up clinical interview.[8] The predictive quality of these screening questionnaires has not been conclusively validated so it is not possible to determine if those identified at risk of suicide will actually commit suicide.[9] Asking about or screening for suicide does not create or increase the risk.[10]

In approximately 75 percent of completed suicides, the individuals had seen a physician within the year before their death, including 45 to 66 percent within the prior month. Approximately 33 to 41 percent of those who completed suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year, including 20 percent within the prior month. These studies suggest an increased need for effective screening.[11][12][13][14][15] Many suicide risk assessment measures are not sufficiently validated, and do not include all three core suicidality attributes (i.e., suicidal affect, behavior, and cognition).[16]

Underlying condition

The conservative estimate is that 10% of individuals with psychiatric disorders may have an undiagnosed medical condition causing their symptoms,[17] upwards of 50% may have an undiagnosed medical condition which if not causing is exacerbating their psychiatric symptoms.[18][19] Illegal drugs and prescribed medications may also produce psychiatric symptoms.[20] Effective diagnosis and if necessary medical testing which may include neuroimaging[21] to diagnose and treat any such medical conditions or medication side effects may reduce the risk of suicidal ideation as a result of psychiatric symptoms, most often including depression, which are present in up to 90–95% of cases.[22]

Interventions

Many methods have been developed in an effort to prevent suicide. The general methods include: direct talks, screening for risks, lethal means reduction and social intervention. The medication lithium may be useful in certain situations to reduce the risk of suicide.[23][24] Talk therapies[25] including phone delivery of services may also help.[26]

Direct talks

An effective way to assess suicidal thoughts is to talk with the person directly, to ask about depression, and assess suicide plans as to how and when it might be attempted.[27] Contrary to popular misconceptions, talking with people about suicide does not plant the idea in their heads.[27] However, such discussions and questions should be asked with care, concern and compassion.[27] The tactic is to reduce sadness and provide assurance that other people care. The WHO advises to not say everything will be all right nor make the problem seem trivial, nor give false assurances about serious issues.[27] The discussions should be gradual and specifically executed when the person is comfortable about discussing his or her feelings. ICARE (Identify the thought, Connect with it, Assess evidences for it, Restructure the thought in positive light, Express or provide room for expressing feelings from the restructured thought) is a model of approach used here.[27][28]

Lethal means reduction

Means reduction, reducing the odds that a suicide attempter will use highly lethal means, is an important component of suicide prevention.[29] This practice is also called "means restriction".

Researchers and health policy planners have theorized and demonstrated that restricting lethal means can help reduce suicide rates, as delaying action until depression passes.[30] In general, strong evidence supports the effectiveness of means restriction in preventing suicides.[31] There is also strong evidence that restricted access at so-called suicide hotspots, such as bridges and cliffs, reduces suicides, whereas other interventions such as placing signs or increasing surveillance at these sites appears less effective.[32] One of the most famous historical examples, of means reduction, is that of coal gas in the United Kingdom. Until the 1950s, the most common means of suicide in the UK was poisoning by gas inhalation. In 1958, natural gas (virtually free of carbon monoxide) was introduced, and over the next decade, comprised over 50% of gas used. As carbon monoxide in gas decreased, suicides also decreased. The decrease was driven entirely by dramatic decreases in the number of suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning.[33][34]

In the United States, numerous studies have concluded that firearm access is associated with increased suicide completion.[35] "About 85% of attempts with a firearm are fatal: that's a much higher case fatality rate than for nearly every other method. Many of the most widely used suicide attempt methods have case fatality rates below 5%."[36][37] Although restrictions on access to firearms have reduced firearm suicide rates in other countries, such restrictions were not feasible in the United States because the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution based on late 1600s English bill of rights limits the potential for regulation laws but broadly restricting firearms access to at-risk individuals is gaining stakeholder's attention as a preventive measure.[38]

Social intervention

National Strategy for Suicide Prevention promotes and sponsors various specific suicide prevention endeavors:

- Developing groups led by professionally trained individuals for broad-based support for suicide prevention.

- Promoting community-based suicide prevention programs.

- Screening and reducing at-risk behavior through psychological resilience programs that promotes optimism and connectedness.

- Education about suicide, including risk factors, warning signs, stigma related issues and the availability of help through social campaigns.

- Increasing the proficiency of health and welfare services at responding to people in need. e.g., Sponsored training for helping professionals, Increased access to community linkages, employing crisis counseling organizations.

- Reducing domestic violence and substance abuse through legal and empowerment means are long-term strategies.

- Reducing access to convenient means of suicide and methods of self-harm. e.g., toxic substances, poisons, handguns.

- Reducing the quantity of dosages supplied in packages of non-prescription medicines e.g., aspirin.

- School-based competency promoting and skill enhancing programs.

- Interventions and usage of ethical surveillance systems targeted at high-risk groups.

- Improving reporting and portrayals of negative behavior, suicidal behavior, mental illness and substance abuse in the entertainment and news media.

- Research on protective factors & development of effective clinical and professional practices.

It has also been suggested by NSSP that media should prevent romanticising of negative emotions and coping strategies which can lead to vicarious traumatization. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (from a 1994 workshop) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (1999) have suggested that TV shows and news media can help prevent suicide by linking suicide with negative outcomes such as pain for the suicide and their survivors, conveying that the majority of people choose something other than suicide in order to solve their problems, avoiding mentioning suicide epidemics, and avoiding presenting authorities or sympathetic, ordinary people as spokespersons for the reasonableness of suicide.[39]

Postvention

Postvention is for people affected by an individual's suicide, this intervention facilitates grieving, guides to reduce guilt, anxiety, and depression and to decrease the effects of trauma. Bereavement is ruled out and promoted for catharsis and supporting their adaptive capacities before intervening depression and any psychiatric disorders. Postvention is also provided to intervene to minimize the risk of imitative or copycat suicides, but there is a lack of evidence based standard protocol. But the general goal of the mental health practitioner is to decrease the likelihood of others identifying with the suicidal behavior of the deceased as a coping strategy in dealing with adversity.[40]

Medication

Recent research has shown that lithium has been effective with lowering the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder to the same levels as the general population.[41] Lithium has also proven effective in lowering the suicide risk in those with unipolar depression as well.[42]

Counseling

There are multiple evidence-based psychotherapeutic talk therapies available to reduce suicidal ideation such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for which multiple studies have reported varying degrees of clinical effectiveness in reducing suicidality. Benefits include a reduction in self-harm behaviours and suicidal ideations.[43][44] Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP) is a form of DBT adapted for adolescents at high risk for repeated suicide attempts.[45][46]

The World Health Organization recommends "specific skills should be available in the education system to prevent bullying and violence in and around the school premises in order to create a safe environment free of intolerance".[47]

Coping planning

Coping planning is an innovative strengths-based intervention that aims to meet the needs of people who ask for help, including those experiencing suicidal ideation.[48] By addressing why someone asks for help, the risk assessment and management stays on what the person needs, and the needs assessment focuses on the individual needs of each person.[49][50] The Coping Planning approach to suicide prevention draws on the health-focused theory of coping. Coping is normalized as a normal and universal human response to unpleasant emotions and interventions are considered a change continuum of low intensity (e.g. self-soothing) to high intensity support (e.g. professional help). By planning for coping, it supports people who are distressed and provides a sense of belongingness and resilience in treatment of illness.[51][52] The proactive coping planning approach overcomes implications of ironic process theory.[53]The biopsychosocial[54] strategy of training people in healthy coping improves emotional regulation and decreases memories of unpleasant emotions.[55] A good coping planning strategically reduces the inattentional blindness for a person while developing resilience and regulation strengths.[56]

Support groups

Many non-profit organizations exist, such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention in the United States, which serve as crisis hotlines; it has benefited from at least one crowd-sourced campaign.[57] The first documented program aimed at preventing suicide was initiated in 1906 in both New York, the National Save-A-Life League and in London, the Suicide Prevention Department of the Salvation Army.[58]

Suicide prevention interventions fall into two broad categories: prevention targeted at the level of the individual and prevention targeted at the level of the population.[59] To identify, review, and disseminate information about best practices to address specific objectives of the National Strategy Best Practices Registry (BPR) was initiated. The Best Practices Registry of Suicide Prevention Resource Center is a registry of various suicide intervention programs maintained by the American Association of Suicide Prevention. The programs are divided, with those in Section I listing evidence-based programs: interventions which have been subjected to indepth review and for which evidence has demonstrated positive outcomes. Section III programs have been subjected to review.[60][61]

Model of suicide

Van Orden et al. (2010) posited that there are two major factors involved in suicide attempts. The first major factor is a desire for death and the second acquired capability. Desire for death occurs through ideations of thwarted belongingness. It is described as feeling alienated from others emotionally and perceived burdensomeness which is described as feeling that one is incompetent and therefore a burden on others.[62] The acquired capability in this context is used because people naturally fear death and painful experiences. The capability to carry out the suicide attempt is usually formed from emotional and physical pain and disrupted cognitive status and is acquired through previous suicide attempts (self-directed violence), rehearsing suicide through behavior or imagery, and getting used to painful or dangerous experiences in other ways.

Individuals who are suicidal often have tunnel vision about the situation and consider permanence of suicide as an easy way out of a difficult situation.[63] Other significant risk factors for suicide include psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, etc.[64][65] Individuals who have good interpersonal social relationship and family support tend to have lower risk of suicide.[66] People who have greater self-control, greater self-efficacy, intact reality-testing, and more adaptive coping skills are at less risk. Those who are hopeful, have future plans or events to look forward to, and have satisfaction in life are considered to have protective factors against suicide.[67]

Strategies

Suicide is the act of deliberately killing oneself or, more specifically, an act deliberately initiated and performed by the person concerned in the full knowledge, or expectation, of its fatal outcome.[68]

In recognition of the need for comprehensive approaches to suicide prevention, various strategies have been developed with the support of evidence. The traditional approach has been to identify the risk factors that increase suicide or self-harm, though meta-analysis studies suggest that suicide risk assessment might not be useful and recommend immediate hospitalization of the person with suicidal feelings as the healthy choice.[69] In 2001, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under the direction of the Surgeon General, published the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, establishing a framework for suicide prevention in the U.S. The document calls for a public health approach to suicide prevention, focusing on identifying patterns of suicide and suicidal ideation throughout a group or population (as opposed to exploring the history and health conditions that could lead to suicide in a single individual).[70] The ability to recognize warning signs of suicide allows individuals who may be concerned about someone they know to direct them to help.[4]

Suicide gesture and suicidal desire (a vague wish for death without any actual intent to kill oneself) are potentially self-injurious behaviors that a person may use to attain some other ends, like to seek help, punish others, or to receive attention. This behavior has the potential to aid an individual’s capability for suicide and can be considered as a suicide warning, when the person shows intent through verbal and behavioral signs.[71]

Specific strategies

Suicide prevention strategies focus on reducing the risk factors and intervening strategically to reduce the level of risk. Risk and protective factors, unique to the individual can be assessed by a qualified mental health professional.

Some of the specific strategies used to address are:

- Crisis intervention.

- Structured counseling and psychotherapy.

- Hospitalization for those with low adherence to collaboration for help and those who require monitoring & secondary symptom treatment.

- Supportive therapy like substance abuse treatment, Psychotropic medication, Family psychoeducation and Access to emergency phone call care with emergency rooms, suicide prevention hotlines...etc.

- Restricting access to lethality of suicide means through policies and laws.

- Creating & using crisis cards, an uncluttered card formatted readably that describes list of activities one should follow in crisis still the positive behavior responses settles in the personality.

- Person-centered life skills training. e.g., Problem solving.

- Registering with support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, Suicide Bereavement Support Group, a religious group with flow rituals, etc.

- Therapeutic recreational therapy that improves mood.

- Motivating self-care activities like physical exercise's and meditative relaxation.

Psychotherapies that have shown most successful or evidence based are Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), it has shown to be helpful in reducing suicide attempts and reducing hospitalizations for suicidal ideation[72] and Cognitive therapy (CBT), it has shown to improve problem-solving and coping abilities.[73]

Preventative Factors

Individuals with access to proper mental health care, a sense of belonging, good problem solving skills, and a system of beliefs that discourages suicide are less likely to attempt suicide.[74]

Economics

In the United States it is estimated that an episode of suicide results in costs of about $1.3 million. Money spending on appropriated interventions is estimated to result in a decrease in economic loses that are 2.5 fold greater than the amount spent.[75]

See also

References

- ↑ "Maine Suicide Prevention Website". Maine.gov. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ January 15, 2012 (2003-09-16). "Suicide prevention definition - Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". Medterms.com. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Packman, Pennuto, Bongar, & Orthwein, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 "NIMH » Suicide Prevention". www.nimh.nih.gov.

- ↑ American Association of Suicidology

- ↑ Office of the Surgeon General:The Surgeon General's Call To Action To Prevent Suicide 1999

- ↑ Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon: International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p. 510

- ↑ Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon, International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p.361; Wiley-Blackwell (2011), ISBN 0-470-68384-8

- ↑ Alan F. Schatzberg: The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders, p. 503: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2005) ISBN 1-58562-151-X

- ↑ Crawford, MJ; Thana, L; Methuen, C; Ghosh, P; Stanley, SV; Ross, J; Gordon, F; Blair, G; Bajaj, P (May 2011). "Impact of screening for risk of suicide: randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 198 (5): 379–84. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083592. PMID 21525521.

- ↑ Depression and Suicide at eMedicine

- ↑ González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW (January 2010). "Depression Care in the United States: Too Little for Too Few". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. PMC 2887749. PMID 20048221.

- ↑ Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL (June 2002). "Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (6): 909–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. PMC 5072576. PMID 12042175.

- ↑ Lee HC, Lin HC, Liu TC, Lin SY (June 2008). "Contact of mental and nonmental health care providers prior to suicide in Taiwan: a population-based study". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (6): 377–83. PMID 18616858.

- ↑ Pirkis J, Burgess P (December 1998). "Suicide and recency of health care contacts. A systematic review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (6): 462–74. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.6.462. PMID 9926074.

- ↑ Harris K. M.; Syu J.-J.; Lello O. D.; Chew Y. L. E.; Willcox C. H.; Ho R. C. M. (2015). "The ABC's of suicide risk assessment: Applying a tripartite approach to individual evaluations". PLoS ONE. 10 (6): e0127442. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127442. PMC 4452484. PMID 26030590.

- ↑ Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, Faillace LA, Stickney SK (November 1978). "Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1315–20. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350041003. PMID 568461.

- ↑ Chuang L., Mental Disorders Secondary to General Medical Conditions; Medscape;2011 Archived October 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D (December 1996). "Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review". Psychiatr Serv. 47 (12): 1356–63. doi:10.1176/ps.47.12.1356. PMID 9117475.

- ↑ Kamboj MK, Tareen RS (February 2011). "Management of nonpsychiatric medical conditions presenting with psychiatric manifestations". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 58 (1): 219–41, xii. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.10.008. PMID 21281858.

- ↑ Andreas P. Otte, Kurt Audenaert, Kathelijne Peremans, Nuclear Medicine in Psychiatry: Functional Imaging of Suicidal Behavior, pp.475–483, Springer (2004); ISBN 3-540-00683-4

- ↑ Patricia D. Barry, Suzette Farmer; Mental health & mental illness, p. 282, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;(2002) ISBN 0-7817-3138-0

- ↑ Randolph B. Schiffer, Stephen M. Rao, Barry S. Fogel, Neuropsychiatry: Neuropsychiatry of suicide, pp. 706-713, (2003) ISBN 0781726557

- ↑ Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, Geddes JR (October 2005). "Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials". Am J Psychiatry. 162 (10): 1805–19. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1805. PMID 16199826.

- ↑ Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. (July 2006). "Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 63 (7): 757–66. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. PMID 16818865.

- ↑ Marasinghe RB, Edirippulige S, Kavanagh D, Smith A, Jiffry MT. "Telehealth approaches to suicide prevention: a review of evidences." eHealth Sri Lanka 2010 2010,1(suppl.1):S8

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Preventing Suicide - A Resource for Primary Health Care Workers" (PDF), World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ George A.F. Seber (2013). Counseling Issues: A Handbook For Counselors And Psychotherapists. Xlibris Corporation. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-4797-5740-4.

- ↑ "Means Matter Campaign". Hsph.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Suicide Prevention Resource Center - Lethal Means

- ↑ Yip, PS; Caine, E; Yousuf, S; Chang, SS; Wu, KC; Chen, YY (23 June 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". Lancet. 379 (9834): 2393–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. PMID 22726520.

- ↑ Cox, GR, Robinson, J, Nicholas, A; et al. (March 2013). "Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review". BMC Public Health. 13: 214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-214. PMC 3606606. PMID 23496989.

- ↑ "Means Matter Campaign - Coal Gas Case". Hsph.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Kreitman, N (Jun 1976). "The Coal Gas Story: United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-1971". Br J Prev Soc Med. 30 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1136/jech.30.2.86. PMC 478945. PMID 953381.

- ↑ "Means Matter - Risk". Hsph.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ "Firearm Access is a Risk Factor for Suicide - Means Matter Basics - Means Matter - Harvard School of Public Health". Hsph.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ "Cdc Mmwr". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Mann, J. John; Michel, Christina A. (22 July 2016). "Prevention of Firearm Suicide in the United States: What Works and What Is Possible". American Journal of Psychiatry. 173: appi.ajp.2016.1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010069. PMID 27444796.

- ↑ R. F. W. Diekstra. Preventive strategies on suicide.

- ↑ "Summary of the Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Suicidal Behavior". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 40 (4): 495–499. 2001. doi:10.1097/00004583-200104000-00024. ISSN 0890-8567.

- ↑ Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J (2003). "Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 Suppl 5: 44–52. PMID 12720484.

- ↑ Coppen A (2000). "Lithium in unipolar depression and the prevention of suicide". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 9: 52–6. PMID 10826662.

- ↑ Canadian Agency for Drugs and technology in Health: "Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in Adolescents for Suicide Prevention: Systematic Review of Clinical-Effectiveness," CADTH Technology Overviews, Volume 1, Issue 1, March 2010 Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ National Institute of Mental Health: Suicide in the U.S.: Statistics and Prevention

- ↑ Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA, et al. (October 2009). "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 48 (10): 1005–13. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbfe. PMC 2888910. PMID 19730273.

- ↑ https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/511760/Child-and-youth-suicide-workshop.pdf

- ↑ "Preventing Suicide, a resource for teachers and other school staff, World Health Organization, Geneva 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ .Stallman, H. M. (2018). Coping Planning: A patient- and strengths-focused approach to suicide prevention training. Australasian Psychiatry, 26(2):141-144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856217732471

- ↑ Stallman, H. M. (2017). Meeting the needs of patients who have suicidal thoughts presenting to Emergency Departments. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 29(6), 749. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.12867

- ↑ Franklin, JC, Ribeiro, JD, Fox, KR. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 2016; 143: 187–232. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000084

- ↑ Stallman, H. M. & Wilson, C. J. (2018). Can the mental health of Australians be improved by dual strategy for promotion and prevention? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417752070

- ↑ Stallman, H. M., Ohan, J. L. (2018). The alignment of law, practice and need in suicide prevention. BJPsych Bulletin, Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2017.3

- ↑ Wegner, Daniel M. (1989). White Bears and Other Unwanted Thoughts: Suppression, Obsession, and the Psychology of Mental Control. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0670825226

- ↑ Engel G. L. (1980). "The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model". American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (5): 535–544. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. PMID 7369396.

- ↑ Katsumi, Y. & Dolcos, S. (2018). Suppress to feel and remember less: Neural correlates of explicit and implicit emotional suppression on perception and memory. Neuropsychologia, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.02.010

- ↑ Stallman, H. M. & Wilson, C. J. (2018). Can the mental health of Australians be improved by dual strategy for promotion and prevention? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417752070

- ↑ http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/137409-GamerGate-Leads-to-Suicide-Prevention-Charity

- ↑ Bertolote, 2004

- ↑ Bertolote, Jose (October 2004). "Suicide Prevention: at what level does it work?". World Psychiatry. 3 (3): 147–151. PMC 1414695. PMID 16633479.

- ↑ Best Practices Registry (BPR) For Suicide Prevention Archived 2011-10-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rodgers PL, Sudak HS, Silverman MM, Litts DA (April 2007). "Evidence-based practices project for suicide prevention". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 37 (2): 154–64. doi:10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.154. PMID 17521269.

- ↑ Ribeiro & Joiner, 2009

- ↑ Kraft, Jobes, Lineberry, Conrad, & Kung, 2010

- ↑ Van Orden et al., 2010

- ↑ Schwartz-Lifshitz M, Zalsman G, Giner L, Oquendo MA (2012). "Can we really prevent suicide?". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 14: 624–33. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0318-3. PMC 3492539. PMID 22996297.

- ↑ Rudd, 2006

- ↑ Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, 2002

- ↑ WHO, 1998

- ↑ Murray, Declan; Devitt, Patrick. "Suicide Risk Assessment Doesn't Work". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "National Strategy for Suicide Prevention" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Joiner, 2005; Wingate et al., 2004; Rudd, 2006

- ↑ Linehan et al., 2006

- ↑ Stellrecht et al., 2006

- ↑ Robert I. Simon (20 May 2008). Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Guidelines for Clinically Based Risk Management. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-58562-726-4.

- ↑ "Costs of Suicide". www.sprc.org. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

Further reading

- Suicide prevention and assessment handbook, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2011.

- Nancy Boyd-Franklin; Elizabeth N. Cleek; Matt Wofsy; Brian Mundy (2013). "Risk Assessment and Suicide Prevention". Therapy in the Real World: Effective Treatments for Challenging Problems. Guilford Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-4625-1034-4.

- Van Orden K. A.; et al. (2010). "The interpersonal theory of suicide". Psychological Review. 117: 575–600. doi:10.1037/a0018697.

External links

- CDC website on Suicide Prevention

- The Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) provides prevention support, training, and resources to assist organizations and individuals to develop suicide prevention programs, interventions and policies, and to advance the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

- Centre for Suicide Prevention (CSP), Canada

- Suicide Prevention:Effectiveness and Evaluation A 32-page guide from SPAN USA, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, and Education Development Center, Inc.

- International Association for Suicide Prevention Organization co-sponsors World Suicide Prevention Day on September 10 every year with the World Health Organization (WHO).

- U.S. Surgeon General - Suicide Prevention

- Suicide Risk Assessment Guide - VA Reference Manual

- Self-harm care management, NICE, UK

- Practice Guidelines for Suicide prevention, APA