Suicide in the United States

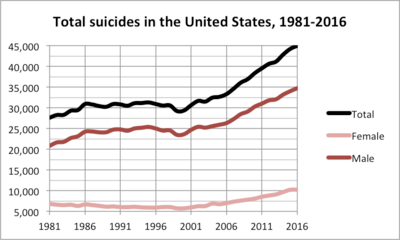

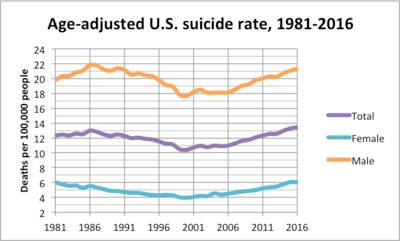

Suicide is a major national public health issue in the United States. In 2016, there were 44,965 recorded suicides,[2] up from 42,773 in 2014, according to the CDC's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).[3][4][5] On average, adjusted for age, the annual U.S. suicide rate increased 24% between 1999 and 2014, from 10.5 to 13.0 suicides per 100,000 people, the highest rate recorded in 28 years.[6][7] Due to the stigma surrounding suicide, it is suspected that it generally is underreported.[8] In April 2016, the CDC released data showing that the suicide rate in the United States had hit a 30-year high,[9][10] and later in June 2018, released further data showing that the rate has continued to increase and has increased in every U.S. state except Nevada since 1999.[11][12]

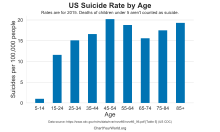

In 2015, suicide was the seventh leading cause of death for males and the 14th leading cause of death for females.[13] Additionally, it was the second leading cause of death for young people aged 15 to 24 and the third leading cause of death for those between the ages of 10 and 14.[14] From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate among Americans aged 35 to 64 increased nearly 30 percent. The largest increases were among men in their fifties, with rates rising nearly 50 percent, and for women aged 60 to 64, with rates rising 60 percent.[7] In 2008, it was observed that U.S. suicide rates, particularly among middle-aged white women, had increased, although the causes were unclear.[15]

A study done by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention in 2014 stated that suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S., imposing a cost of $51 billion to the US annually.[8][13] Other additional facts showed by the study were:[8]

- The annual age-adjusted suicide rate is 13.26 per 100,000 individuals.

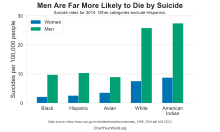

- Men die by suicide 3.5x more often than women.

- Women attempt suicide 2x more often than men.

- On average, there are 121 suicides per day.

- White males accounted for 7 of 10 suicides in 2015.

- A firearm is used in almost 50% of all suicides.

- The rate of suicide is highest in middle age—white men in particular.

The U.S. government seeks to prevent suicides through its National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, a collaborative effort of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Indian Health Service.[16] Their plan consists of eleven goals aimed at preventing suicides.[17] Older adults are disproportionately likely to die by suicide.[18] Some U.S. jurisdictions have laws against suicide or against assisting suicide. In recent years, there has been increased interest in rethinking these laws.[19] These policies focus on the recovery of the individual through the treatment of the mental disease. The aim is to assure the wellness and the health of the person affected as well as make sure that they recover and take advantage of their all potential.[20]

Suicide has been associated with tough economic conditions, including unemployment rate.[21]

There are significant variations in the suicide rates of the different states,[22] ranging from 28.24 per 100,000 people in Wyoming to 7.81 per 100,000 people in New York.[8]

Approximately half of suicides are committed using a firearm, accounting for two-thirds of all firearm deaths.[23] Firearms were used in 56.9% of suicides among males in 2016, making it the most commonly used method by them.[13]

Number of suicides by age group and sex

The National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) keeps data on U.S. suicides.

| Age (years) | 10 – 14 | 15 – 24 | 25 – 34 | 35 – 44 | 45 – 54 | 55 – 64 | 65 – 74 | 75+ | Unknown | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 265 | 4575 | 5887 | 5294 | 6198 | 5745 | 3463 | 3291 | 2 | 34727 |

| Females | 171 | 1148 | 1479 | 1736 | 2239 | 2014 | 940 | 510 | 1 | 10238 |

| Male/Female Ratio | 1.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 3.4 |

| Total | 436 | 5723 | 7366 | 7030 | 8437 | 7759 | 4403 | 3801 | 3 | 44965 |

Based on the NVDRS 2016 data, the New York Times acknowledged that, among men, those over 65—who make up a smaller proportion of the population—are at greatest risk of death by suicide.[24] The NVDRS 2015 data showed that, among men of all races, men over 65 were the most likely to commit suicide (27.67 suicides per 100,000), closely followed by men 40–64 (27.10 suicides per 100,000). Men 20–39 (23.41 per 100,000) and 15–19 (13.81 per 100,000) were less likely to commit suicide.[25]

Murder–suicide

There have been many high-profile incidents in the United States in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s of individuals thought to be attempting "suicide by cop" or killing others before killing themselves. Examples include the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, the 2010 Austin plane crash, the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting and the 2014 Isla Vista killings.

Rates compared to other countries

| Suicide |

|---|

|

|

Related phenomena |

Subgroups

By state

There are significant variations in the suicide rates of the different states.[22] A number of theories for these differences have been suggested, ranging from socioeconomics to access to firearms and isolation (low population densities),[26] and a study in 2011 found a correlation between altitude above sea level and suicide.[27]

| Suicide rate by state (2016)[28] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | State | Suicide rate per 100,000 people |

| 1 | Montana | 25.9 |

| 2 | Alaska | 25.8 |

| 3 | Wyoming | 25.2 |

| 4 | New Mexico | 22.5 |

| 5 | Utah | 21.8 |

| 6 | Idaho | 21.4 |

| 7 | Nevada | 21.4 |

| 8 | Oklahoma | 21.0 |

| 9 | Colorado | 20.5 |

| 10 | South Dakota | 20.2 |

| 11 | West Virginia | 19.3 |

| 12 | North Dakota | 19.0 |

| 13 | Missouri | 18.4 |

| 14 | Arkansas | 18.2 |

| 15 | Kansas | 17.9 |

| 16 | Oregon | 17.8 |

| 17 | Arizona | 17.7 |

| 18 | Vermont | 17.3 |

| 19 | New Hampshire | 17.2 |

| 20 | Kentucky | 16.8 |

| 21 | Tennessee | 16.8 |

| 22 | Maine | 15.9 |

| 23 | Alabama | 15.7 |

| 24 | South Carolina | 15.7 |

| 25 | Indiana | 15.4 |

| 26 | Washington | 14.9 |

| 27 | Pennsylvania | 14.7 |

| 28 | Wisconsin | 14.7 |

| 29 | Iowa | 14.6 |

| 30 | Louisiana | 14.2 |

| 31 | Ohio | 14.2 |

| 32 | Florida | 14.0 |

| 33 | Georgia | 13.3 |

| 34 | Michigan | 13.3 |

| 35 | Minnesota | 13.2 |

| 36 | Virginia | 13.2 |

| 37 | Nebraska | 13.1 |

| 38 | North Carolina | 13.0 |

| 39 | Mississippi | 12.7 |

| 40 | Texas | 12.6 |

| 41 | Hawaii | 12.1 |

| 42 | Delaware | 11.5 |

| 43 | Rhode Island | 11.2 |

| 44 | Illinois | 10.7 |

| 45 | California | 10.5 |

| 46 | Connecticut | 10.1 |

| 47 | Maryland | 9.4 |

| 48 | Massachusetts | 8.8 |

| 49 | New York | 8.1 |

| 50 | New Jersey | 7.2 |

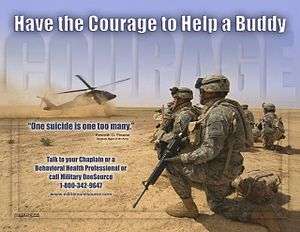

Military

A 2009 U.S. Army report indicates military veterans have double the suicide rate of non-veterans, and more active-duty soldiers have died from suicide than in combat in the Iraq War (2003–2011) and War in Afghanistan (2001–2014).[29] Colonel Carl Castro, director of military operational medical research for the Army noted "there needs to be a cultural shift in the military to get people to focus more on mental health and fitness."[30] In 2012, the US Army reported 185 suicides among active-duty troops, exceeding the number of combat deaths in that year (176). This figure has significantly increased since 2001, when the number of suicides was 52.[31]

LGBTQ

Attempted suicide rates for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and adults in the U.S. are three times higher than national averages.[32]

Chronic Pain

Patients with chronic pain are twice as likely to attempt suicide compared with those without chronic pain.[33]

Autism

Studies have found very high rates of suicide in people with autism spectrum disorders, including high functioning autism and what was formerly known as Asperger syndrome. Autism and particularly Asperger syndrome are highly associated with clinical depression and as many as 30 percent or more of people with Asperger syndrome also suffer from depression.[34]

One study found that children with autism are 28 times more likely to ideate or attempt suicide than the general population.[35] Another study found that being an adult and having Asperger syndrome increases the suicide risk 10 fold.[36]

This may be related to the shunning, harassment, stigma, and violence that is commonly perpetrated upon people with autism. One study found that 18.5% of American children with autism had been physically abused and 16.5% had been sexually abused.[37] People with autism are much more likely to be sexually abused than the general population.[38]

Another possible factor is the likely increased prevalence of chronic pain in people with autism, contrary to the popular belief that autistic people are insensitive to pain.[39] Autism has been found to be closely related to fibromyalgia, a common chronic pain disorder.[40]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports".

- 1 2 2016, United States: Suicide Injury Deaths and Rates per 100,000. (All Races, Both Sexes, All Ages)". Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports – CDC.

- ↑ "Products – Data Briefs – Number 241 – April 2016". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Data Brief 241: Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014 : Data table for Figure 1. Age-adjusted suicide rates, by sex: United States, 1999–2014" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Deaths: Final Data for 2014" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina (22 April 2016). "U.S. Suicide Rate Surges to a 30-Year High". NYTimes.com.

- 1 2 TARA PARKER-POPE (May 2013). "Suicide Rates Rise Sharply in U.S."

- 1 2 3 4 "Suicide Statistics — AFSP". AFSP. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ↑ "U.S. suicide rate surges to three decade high". Chicago Tribune. Tronc. April 22, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina (April 22, 2016). "U.S. Suicide Rate Surges to a 30-Year High". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Maggie, Fox (June 7, 2018). "Suicide rates are up 30 percent since 1999, CDC says". NBC News. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Hedegaard, Holly; Curtin, Sally C.; Warner, Margaret (June 2018). Suicide Rates in the United States Continue to Increase (PDF). NCHS Data Brief No. 309 (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- 1 2 3 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf

- ↑ "Suicide". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Suicide Rate Increases". Jhsph.edu. 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ "Suicide Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration". Mentalhealth.samhsa.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ "Substance Abuse and Mental Health Publications| SAMHSA Store". Mentalhealth.samhsa.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ Tuesday, 17 February 2009 12:05 (2009-02-17). "In Harm's Way: Suicide in America – MHM: Suicide". Mental-health-matters.com. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ Engelhardt, H. Tristram Jr.; Malloy, Michele (1982–1983), Suicide and Assisting Suicide: A Critique of Legal Sanctions, 36, Sw. L.J., p. 1003

- ↑ ASPA (2013-03-12). "Recovery is Possible". Mentalhealth.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ↑ DS Hamermesh; NM Soss (1974), An economic theory of suicide, The journal of political economy, JSTOR 1830901

- 1 2 "2015 Annual Report". America's Health Rankings. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ↑ "FastStats". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Span, Paula (25 May 2018). "In Elderly Hands, Firearms Can Be Even Deadlier Image". New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ "National Violent Death Reporting System". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, J. (14 January 2015). "Is altitude causing suicide in the West?". High Country News. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ↑ Barry Brenner; David Cheng; Sunday Clark (2011), "Positive Association between Altitude and Suicide in 2584 U.S. Counties", High Alt. Med. Biol., High Altitude Medicine and Biology, 12: 31–5, doi:10.1089/ham.2010.1058, PMC 3114154, PMID 21214344

- ↑ "Stats of the State – Suicide Mortality". www.cdc.gov. 11 January 2018.

- ↑ Woods, Tyler (September 7, 2009). "This Week Is National Suicide Prevention Week". Emax Health. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ Jelinek, Pauline (September 5, 2008). "Army: soldier suicide rate may set record again". USA Today/Associated Press. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ Wood, David (September 25, 2013). "Army Chief Ray Odierno Warns Military Suicides 'Not Going To End' After War Is Over". Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ Melin, Amy (September 11, 2008). "AFSP walkathon raises suicide awareness". Western Herald. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ "Patients With Chronic Pain Are Twice as Likely to Attempt Suicide". Clinical Pain Advisor. 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Johnny L. Matson; Marie S. Nebel-Schwalm. "Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: An overview" (PDF). Vcuautismcenter.org. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "New Research on Autism and Suicide". Psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Suicidal Thoughts 10 Times More Likely in Adults With Asperger's – Psych Central News". Psychcentral.com. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Information for domestic violence and sexual assault counselors" (PDF). Autism-society.org. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Why People With Autism Are At Higher Risk For Sexual Abuse". Medicaldaily.com. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Unseen agony: Dismantling autism's house of pain – Spectrum". Spectrumnews.org. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Johnson B, Ulberg S, Shivale S, Donaldson J, Milczarski B, Faraone SV (2014). "Fibromyalgia, autism, and opioid addiction as natural and induced disorders of the endogenous opioid hormonal system". Discov Med. 18: 209–20. PMID 25336035.