Stefan Lazarević

| Stefan Lazarević | |

|---|---|

| Despot of Serbia | |

|

| |

| Reign |

Knez (1389–1402) Despot (1402–1427) |

| Predecessor | Lazar of Serbia |

| Successor | Đurađ Branković |

| Born |

c. 1377 Kruševac, Moravian Serbia |

| Died |

1427 Glava, Serbian Despotate |

| Burial | Manasija Monastery |

| House | Lazarević |

| Father | Lazar of Serbia |

| Mother | Princess Milica of Serbia |

Stefan Lazarević (Serbian: Стефан Лазаревић, c. 1377–19 July 1427), also known as Stefan the Tall (Стеван Високи), was the ruler of Serbia as prince (1389-1402) and despot (1402-1427). The son of Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović, he was regarded as one of the finest knights and military leaders in Europe. After the death of his father at Kosovo (1389), he became ruler of Moravian Serbia and ruled with his mother Milica (a Nemanjić), until he reached adulthood in 1393. Stefan led troops in several battles as an Ottoman vassal, until asserting independence after receiving the title of despot from the Byzantines in 1402.

Becoming an Hungarian ally in 1403–04, he received large possessions, including the important Belgrade and Golubac Fortress. He also held the superior rank in the chivalric Order of the Dragon. During his reign there was a long conflict with his nephew Đurađ Branković, which ended in 1412. Stefan also inherited Zeta, and waged the war against Venice. Since he was childless, he designated his nephew Đurađ as heir in 1426, a year before his death.

On the domestic front, he broke the resistance of the Serbian nobles, and used the periods of peace to strengthen Serbia politically, economically, culturally and militarily. In 1412 he issued the Code of Mines, with a separate section on governing of Novo Brdo – the largest mine in the Balkans at that time. This code increased the development of mining in Serbia, which has been the main economic backbone of Serbian Despotate. At the time of his death, Serbia was one of the largest silver producers in Europe. In the field of architecture, he continued development of the Morava school. His reign and personal literary works are sometimes associated with early signs of the Renaissance in the Serbian lands. He introduced knightly tournaments, modern battle tactics, and firearms to Serbia. He was a great patron of the arts and culture by providing shelter and support to scholars, and refugees from neighboring countries that have been taken by the Ottomans. In addition, he was himself a writer, and his most important work is A Homage to Love, which is characterized by the Renaissance lines. During his reign the Resava School was formed.

Background and family

Stefan was the son of Lazar and his wife Milica, a lateral line of Nemanjić. Hrebeljanović's father Prince Vratko was a direct descendant of Vukan, eldest son of Stefan Nemanja. In addition to Stefan, they had seven other children.[1][2][3]

| Stefan's brothers and sisters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stefan's brothers | |||

| Name | Lifespan | Title | |

| Dobrovoj | (Died as a child) | ||

| Vuk | (?—1410) | prince | |

| Stefan's sisters | |||

| Name | Lifespan | Marriages | |

| Мara | (?—1426) | Vuk Branković, c. 1371[1][2][4] | |

| Jelena | (?—1443) | 1.Đurađ II Stracimirović Balšić (1385 — 1403), c. 1386[1][2] 2.Sandalj Hranić (1392 — 1435), 1411 | |

| Dragana[3][4] | (?—?) | Ivan (1371 — 1395) or his son Alexander, c. 1386[4] | |

| Teodora (Jelena) | (?—before 1405)[3] | Nikola II Gorjanski, c. 1387[1][2] | |

| Olivera | (c. 1378[1] — after 1443[2][3]/1444[1]) | Bayezid I (1389—1403), 1390 | |

Stefan Lazarević married Jelena in September 1405. Jelena was daughter of Francesco II Gattilusio, a Genovese lord of Lesbos and a sister of Irene Gattilusio, empress of Byzantium and wife of John VII Palaiologos. Stefan and Jelena's marriage was arranged during his stay in Constantinople in 1402, at a time when the city and the Byzantine Empire ruled John VII in the name of his uncle, Manuel II (1373-91 ruler; Emperor 1391-1425). Jelena and Stefan had no children and Jelena is not shown on any frescoes in monasteries built by Stefan.[4]

Early years

Stefan was the son of Prince Lazar, whom he succeeded in 1389. Nikola Zojić attempted to overthrow Stefan Lazarević at the end of 14th century and used Ostrvica as haven after his attempt failed.[5]

Lazarević participated as an Ottoman vassal in the Battle of Rovine in 1395, the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, and in the Battle of Ankara in 1402.[6]

Aftermath of Ankara

The Ottoman defeat at Ankara (July 1402) and disappearance of Sultan Bayezid I provided opportunity for the Serbian magnates to take advantage of the turmoil and pursue independent politics.[7] They returned home from the battlefield via Byzantine territory; in August 1402 at Constantinople, as the new conditions made for closer Byzantine–Serbian cooperation, Stefan Lazarević and his men were not only well-received, but Emperor John VII Palaiologos decided to award him the very high title of Despot.[7]

From Constantinople, Despot Stefan paved the way for an independent Serbia.[8] While staying there, he came to quarrel with another Serbian magnate, his nephew Đurađ Branković. Although the reasons remain unknown, Ragusan chronicler Mavro Orbini (1601) claimed that there were suspicions that Đurađ wanted to join Süleyman Çelebi, Bayezid's oldest son who held power in Rumelia.[8] Despot Stefan ordered Đurađ imprisoned, but his jail-time was short as he was freed with the help of a friend in September 1402.[9]

Đurađ went immediately to Süleyman Çelebi whom he asked for troops to fight the Lazarević.[9] The Lazarević–Branković conflict became an opportunity for the Ottomans, who readied for war, to secure rule in the Balkans. A Serbian contingent that returned home from Asia Minor was abruptly attacked and destroyed near Edirne on the order of an Ottoman commander.[9]

Đurađ and the Ottomans sought to prevent the return of Despot Stefan and his brother Vuk home, so Đurađ's forces were joined by Ottoman bands ordered by Süleyman to take hold of roads and prevent the Lazarević's crossing, which was expected through Branković's lands in Kosovo.[9]

The Lazarević brothers and a detachment of ca. 260 men embarked to the coast of Zeta from Byzantium on ships.[10] Despot Stefan heard of Đurađ's plans. The brothers prepared for fighting and met with their brother-in-law Đurađ II Balšić who supported them militarily, while at the same time an army in Serbia was collected (also by their mother Milica). The Despot's army began their way into the hinterland at the end of October 1402, on detouring roads towards the Žiča monastery.[11]

The two sides clashed on 21 November 1402 at Tripolje, near the Gračanica monastery. While Despot Stefan engaged the Ottoman troops, Vuk's force engaged Đurađ's force. Upon seeing the brave spirit at the battlefield of Despot Stefan, famed for his bravery at Nicopolis (1396) and at Ankara, it is said that the Ottoman soldiers hoped for escape.[12] Uglješa Vlatković gave important information on Ottoman plans, contributing to the outcome of the battle.[13] Despot Stefan in the literally sense "chased Turks by the bunch".[12] Meanwhile, Đurađ caused great damage to Vuk;[14] it was Despot Stefan who decided the battle,[15] having quickly fixed position and completely defeated Đurađ.[14] Constantine of Kostenets wrote how Stefan "bloodied the right hand of his" (slewing),[16] and Orbini wrote that Despot Stefan won the battle "more with strategy than the courage of his soldiers".[14] After the battle, Lazarević brothers withdrew to the fortified city of Novo Brdo.[17]

Despot Stefan managed to take power in the country, with great help from the reputation and work of his mother Milica (who was also politically active). The Lazarević–Branković conflict continued. In December 1402, the Republic of Ragusa expressed great regret of the conflicts in Serbia.[15]

In March 1403, Sultan Bayezid died in Tatar captivity, which ignited a throne war between his four sons. There are accounts that Despot Stefan and Süleyman made truce shortly after the battle.[18] Through the Gallipoli treaty in early 1403, Süleyman promised to not interfere in Serbia, on the condition that the Lazarević accept obligations in effect prior to the battle of Ankara (tribute and troop support).[19] Despot Stefan however continued the war against the Ottomans and the Branković.

.jpg)

Meanwhile, there was a rift between the Lazarević brothers. After the battle at Tripolje, the Lazarević brothers withdrew to the fortified city of Novo Brdo.[20] Constantine of Kostenets wrote "this one [Stefan] with a victory, and this one [Vuk] as defeated".[21] Stefan complained about the casualties under Vuk's command, and wanted Vuk to train in the art of war.[22]

Vuk took it to heart when Stefan said "some hard words" during instructions.[22] Feeling hurt, with a gap between them,[15] Vuk "waited some time, and finding the right time" ran off to Süleyman in the summer of 1403.[22] Kalić believed there was also a disagreement on the division of lands,[15] while Blagojević believes that Stefan's continued opposition against the Ottomans in light of truce played a role. Vuk had thus decided to leave the country and enter the ranks of Süleyman Çelebi.[23]

In order to retain independence from the Ottomans who closed in to the south, Despot Stefan turned to the Kingdom of Hungary, which could be counted on militarily.[24] After becoming a Hungarian vassal (1403), Despot Stefan was offered peace by the Ottomans on his terms, and the Serbian Despotate was no longer a subject of the Ottoman Empire. Vuk returned home and the brothers ruled in accord.[25] The Ottoman–Serbian peace, Hungarian–Serbian alliance, Hungarian ceding of large territories in the north, and finally joining of Uglješa Vlatković and his province, led Despot Stefan to expand his claims on all Serbian lands.[25]

Serbian–Hungarian alliance

Stefan was receptive when Sigismund of Hungary approached him for an alliance. Sigismund was very generous in his terms. Despot Stefan received Mačva, Belgrade (which became Lazarević's capital in 1405), Golubac (an important fortress on the Danube) and other domains, such as lands in Vojvodina (Zemun, Slankamen, Kupinik, Mitrovica, Bečej, and Veliki Bečkerek) in 1404, Apatin in 1417, and Srebrenica in 1411. At Belgrade, he built a fortress with a citadel (which was destroyed during the Great Turkish War in 1690; only the Despot Stefan Tower remains today).

Endowment

Under his rule, he issued a Code of Mines in 1412 in Novo Brdo, the economic center of Serbia. In his legacy, Resava-Manasija monastery (Pomoravlje District), he organized the Resava School, a center for correcting, translating, and transcribing books.

Death

Stefan Lazarević died suddenly in 1427, leaving the throne to his nephew Đurađ Branković. His deeds eventually elevated him into sainthood, and the Serbian Orthodox Church honors him on 1 August. Despot Stefan is buried in the monastery Koporin which he had built in 1402, as he did the bigger and more famous Manasija monastery in 1407. In fact, Manasija was intended as his own burial place, but due to a sudden nature of his death in perilous times it was his brother Vuk that is buried there.

Military life

Works

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Apart from the biographical notes in charters and especially in the Code on The Mine Novo Brdo (1412), Stefan Lazarević wrote three original literary works:

- The Grave Sobbing for prince Lazar (1389)

- The Inscription on the Kosovo Marble Column (1404)

- A Homage to Love (1409), a poetic epistle to his brother Vuk.

He was probably the patron of the most extensively illuminated Serbian manuscript, the Serbian Psalter which is now kept in the Bavarian State Library in Munich.[26]

Resava School

Despot Stefan Lazarević was a great patron of art and culture providing support and shelter to scholars from Serbia and exiles from surrounding countries occupied by the Ottomans. He was educated at his parents’ home, he spoke and wrote Serbo-Slavic; he could speak Greek, and was familiar with Latin.

He was an author in his own right, and his main works include "Slovo ljubve" ("Letter of Love") that he dedicated to his brother Vuk, and "Natpis na mramornom stubu na Kosovo" ("Inscription on the Marble Pillar at Kosovo").

Some of the original works he wrote during his reign have been preserved. During the Despotʼs reign, rich transcribing activity – The Transcription School of Resava – was developed in his foundation, the Manasija Monastery. More Christian works and capital works of ancient civilization were transcribed there than in all times preceding the Despotʼs ruling. By building a spiritual shield to his nation, bequeathing rich spiritual heritage and values rooted in Christian civilization, Stefan Lazarević made it possible for future civilizations to find own spiritual roots, deeply aware that historical recollection cannot exist without linguistic memory.

During the short time the life of the founder and monastery coincided (1407-27), so much was achieved in Resava that it remained an important and outstanding monument in the history of Serbian and Slavic culture in general. It was there that Bulgarian-born Constantine the Philosopher, a reputable "Serbian teacher", translator and historian established the famous orthographic school of Resava, to correct errors in the ecclesiastical literature incurred by numerous translations and incorrect transcriptions, and to thoroughly change the previous orthography.

Constantineʼs essay on how Slavic books should be written recommended a very complicated orthography that subsequently many authors adopted and used for a long time. Regardless of subsequent criticism of this endeavour, the very fact that in Serbia in the 15th century an essay was written on orthography and its rules is very important. But the writing and translation works in Manasija are even more important. Until the very end of the 17th century documents confirm outstanding reputation or translations and transcripts originating from the Resava School.

Titles

- "Lord of all the Serbs and Podunavlje" (господар свих Срба и Подунавља[27]), inherited through his father.[28]

An inscription names him Despot, Lord "of all Serbs and Podunavlje and Posavje and part of Hungarian lands and Bosnian [lands], and also Maritime Zeta" (свим Србљем и Подунављу и Посавју и делом угарске земље и босанске, а још и Поморју зетском).[29]

- "Despot of the Kingdom of Rascia and Lord of Serbia" (Stephanus dei gratia regni Rassia despotus et dominus Servie[30]). After 1402.

- "Despot, Lord of Rascia" (Stephanus Despoth, Dominus Rasciae), in the founding charter of the Order of the Dragon (1408). He was the first on the list.[31]

- "Despot, Lord of all Serbs and the Maritime" (господин всем Србљем и Поморију деспот Стефан).[32]

Marriage

On 12 September 1405, Stefan married Jelena Gattilusio, the daughter of Francesco II of Lesbos. According to Konstantin the Philosopher, Stefan first saw his wife on Lesbos, where Francesco II offered him a choice among his daughters; the marriage was arranged "with the advice and participation" of Jelena's sister, Empress Eirene. Surprisingly, there is no mention of Jelena after her marriage to Stefan; this led Anthony Luttrell to remark that "apparently there were never any children; nothing is known of her death or burial; and, most unusual, she did not appear in any of the post-1402 fresco portraits of Stefan".[33] Luttrell concludes "Maybe she was too young for the marriage to be consummated, and perhaps she stayed on Lesbos and never traveled to Serbia; possibly she died soon after her marriage."[34]

Gallery

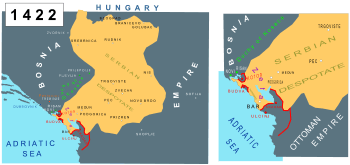

Stefan Lazarević Despotate in 1422

Stefan Lazarević Despotate in 1422 Lazarević dynasty coat of arms

Lazarević dynasty coat of arms- Stefan Lazarević tomb in Manasija monastery

Monument.

Monument.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ivić, Aleksa (1928). Родословне таблице српских династија и властеле. Novi sad: Matica Srpska. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Genealogy - Balkan states: The Lazarevici". Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Medieval Lands project - Serbia: ''Lazar I [1385]-1389, Stefan 1389-1427''". Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Андрија Веселиновић Радош Љушић, "Српске династије" , Нови Сад, 2001. ISBN 86-83639-01-0

- ↑ Đurđe Bošković (1956). Arheološki spomenici i nalazišta u Srbiji: Centralna Srbija. Naučna knjiga. p. 54. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ The Balkans, 1018-1499, M. Dinic, The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4, Ed. J. M. Hussey, (Cambridge University Press, 1966), pg. 551.

- 1 2 Kalić 1982a, p. 65.

- 1 2 Kalić 1982a, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Kalić 1982a, p. 67.

- ↑ Purković 1978, pp. 67–68, Kalić 1982a, p. 67

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 Purković 1978, p. 69.

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, p. 68, Purković 1978, p. 70

- 1 2 3 Purković 1978, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 4 Kalić 1982a, p. 68.

- ↑ Purković 1978, p. 60.

- ↑ Purković 1978, p. 79, Kalić 1982a, p. 68

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, p. 69, Blagojević 1982, p. 115

- ↑ Purković 1978, p. 79, Kalić 1982a, p. 68

- ↑ Trifunović, ed. 1979, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Purković 1978, p. 79.

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, p. 68, Blagojević 1982, p. 115

- ↑ Kalić 1982a, p. 69.

- 1 2 Blagojević 1982, p. 115.

- ↑ "Serbian Psalter, Cod. slav. 4". Bavarian State Library. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Miloš Blagojević (2004). Nemanjići i Lazarevići i srpska srednjovekovna državnost. Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva.

У jедноj хиландарс^' пове- л>и деспот Стефан истиче да jе постао господар свих Срба и Подунавља

- ↑ Istorijski glasnik: organ Društva istoričara SR Srbije. Društvo. 1982.

На основу досадашњег излагања са сигурношћу можемо рећи да деспот Угљеша , господин Константин , Вук Бранковић , Вукови синови и кесар Угљеша никада нису носили титулу " господар Срба и Подунавља " , јер је ова ...

- ↑ Jovan Janićijević (1996). Kulturna riznica Srbije. Izd. Zadruga Idea.

У натпису се каже да је деспот, господар "свим Србљем и Подунављу и Посавју и делом угарске земље и босанске, а још и Поморју зетском"

- ↑ Radovi. 19. 1972. p. 30.

Stephanus dei gra- tia regni Rassia despotus et dominus Servie

- ↑ Ekaterini Mitsiou (2010). Emperor Sigismund and the orthodox world. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-7001-6685-6.

The first name to appear is Stephanus Despoth, Dominus Rasciae

- ↑ Đorđe Trifunović (1979). Књижевни радови. Srpska Književna Zadruga. p. 67.

"Милостију Божијеју господин всем Србљем и Подунавију деспот Стефан"; "Милостију Божијеју го- сподин всем Србљем и Поморију деспот Стефан"; "Ми- лостију Божијеју господин всој земљи ...

- ↑ Anthony Luttrell, "John V's Daughters: A Palaiologan Puzzle", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 40 (1986), pg. 105

- ↑ Luttrell, "John V Daughters", pg. 106

Sources

- Bogdanović, Dimitrije; Mihaljčić, Rade; Ćirković, Sima; Kalić, Jovanka; Kovačević-Kojić, Desanka; Blagojević, Miloš; Babić-Đorđević, Gordana; Đurić, Vojislav J.; Spremić, Momčilo; Božić, Ivan; Pantić, Miroslav; Ivić, Pavle (1982). Kalić, Jovanka, ed. Историја српског народа: Доба борби за очување и обнову државе (1371–1537). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1982a). "Велики преокрет". Историја српског народа: Доба борби за очување и обнову државе (1371–1537). pp. 64–74.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1982b). "Немирно доба". Историја српског народа: Доба борби за очување и обнову државе (1371–1537). pp. 75–87.

- Blagojević, Miloš (1982). "Врховна власт и државна управа". Историја српског народа: Доба борби за очување и обнову државе (1371–1537). pp. 109–127.

- Purković, Miodrag (1978). Knez i despot Stefan Lazarević. Sveti arhijerejski sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve.

- Stojaković, Slobodanka (2006). Деспот Стефан Лазаревић. Српско нумизматичко друштво. ISBN 978-86-902071-6-9.

- Trifunović, Đorđe, ed. (1979). "Stefan Lazarević". Књижевни радови. Srpska književna zadruga. 477.

- Veselinović, Andrija (2006) [1995]. Држава српских деспота [State of the Serbian Despots]. Belgrade: Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. ISBN 86-17-12911-5.

Further reading

- Books

- Life of Despot Stefan Lazarević by Constantine the Philosopher (ca. 1431).

- Braun, Maximilian, ed. (1956). Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević. Mouton.

- Mirković, L., ed. (1936). Живот деспота Стефана Лазаревића. Старе српске биографије XV и XVII века. СКЗ.

- Jagić, V., ed. (1875). "Константин Филозоф, „Живот Стефана Лазаревића"". Гласник Српског ученог друштва. 42: 223–328.

- Journals

- Antonović, Miloš (1992). "Despot Stefan Lazarević i Zmajev red".

- Glušac, Jеlena (2015). "Prince and despot Stefan Lazarević and monastery of Great Lavra of Saint Athanasius on Mount Athos". Zbornik Matice srpske za drustvene nauke. 153: 739–746.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2006). "Despot Stefan and Byzantium". Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. 43: 31–40.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2005). "Despot Stefan i Nikola II Gorjanski".

- Kotseva, Elena (2014). "The Virtues of the Ruler according to the Life of Stefan Lazarević by Constantine of Kostenets". Scripta & e-Scripta. 13: 123–129.

- Krstić, Aleksandar (2015). "Два необјављена латинска писма деспота Стефана Лазаревића" [Two unpublished Latin letters of Despot Stefan Lazarević]. Иницијал. 3: 197–209.

- Mihailović-Milošević, S. (2012). "Literary character of the Despot Stefan Lazarević in The Lives of Constantine Philosopher" (PDF). Baština (32): 41–49.

- Pantelić, Svetlana (2011). "Money of despot Stefan Lazarević (1402-1427)". Bankarstvo. 40 (9–10): 122–127.

- Popović, Mihailo (2010). The Order of the Dragon and the Serbian despot Stefan Lazarević. Emperor Sigismund and the Orthodox World. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-6685-6.

- Petrović, Nebojša (2012). "Viteštvo i Despot Stefan Lazarević" (PDF). Viteška kultura. 1 (1): 23–36.

- Spremić, Momčilo (2008). "Деспот Стефан Лазаревић и "господин" Ђурађ Бранковић" [Despot Stefan Lazarević and "Sir" Đurađ Branković]. Историјски часопис. 56: 49–68.

- Šuica, Marko (2009). "Битка код Никопоља у делу Константина Филозофа" [The Battle of Nicopolis in the work of Constantine the Philosopher]. Историјски часопис. 58: 109–124.

- Šuica, Marko (2013). "O години одласка Кнеза Стефана Лазаревића у Севастију". Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. 50 (2): 803–810.

- Šuica, Marko. "Властела кнеза Стефана Лазаревића (1389-1402)". ГДИ. 1: 7–31.

- Türkmen, İlhan (2013). "Osmanlı'nın Emrinde Bir Sırp Despotu: Stefan Lazareviç" [A Serbian Despot Under The Heel Of The Ottoman Empire: Stefan Lazarevic] (PDF). Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi. 6 (28).

- Symposia

- Ресавска школа и деспот Стефан Лазаревић: округли сто, Манастир Манасија 28.08. 1993. Народна библиотека Ресавска школа. 1994. ISBN 978-86-82379-03-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stefan Lazarević. |

Stefan Lazarević Born: circa 1372/77 Died: 19 July 1427 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lazar of Serbia |

Serbian Prince 1389–1402 |

Vacant Title next held by Đurađ Branković |

| New creation | Serbian Despot 1402–1427 | |