Stari Most

| Stari Most | |

|---|---|

Stari Most in 2006 | |

| Coordinates | 43°20′13.56″N 17°48′53.46″E / 43.3371000°N 17.8148500°ECoordinates: 43°20′13.56″N 17°48′53.46″E / 43.3371000°N 17.8148500°E |

| Carries | Pedestrians |

| Crosses | Neretva |

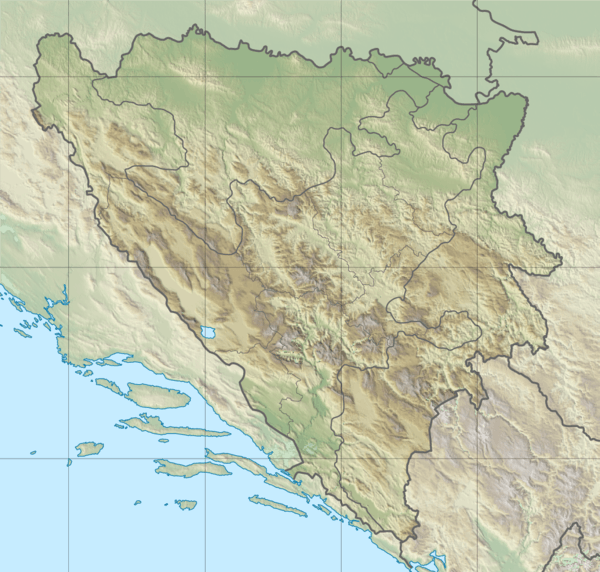

| Locale | Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Official name | Stari most |

| Heritage status | KONS listed[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | arch bridge |

| Material | stone |

| Total length | 29 metres |

| Width | 4 metres |

| No. of spans | 1 |

| Clearance below | cca.20 metres at mid-span depending on river water-level |

| History | |

| Architect | Mimar Hayruddin (concept could originate from Mimar Sinan idea) |

| Constructed by | Mimar Hayruddin, apprentice of Mimar Sinan |

| Construction start | 1557 |

| Construction end | 1566 |

| Opened | 1567 |

| Rebuilt | 7 June 2001 – 23 July 2004 |

| Collapsed | 9 November 1993 |

| Official name | Old Bridge Area of the Old City of Mostar |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 2005 (29th session) |

| Reference no. | 946 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Europe and North America |

Stari Most in Old Town of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

Stari Most (literally, "Old Bridge") is a rebuilt 16th-century Ottoman bridge in the city of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina that crosses the river Neretva and connects the two parts of the city. It was built by Mimar Hayruddin, apprentice of the famous architect Mimar Sinan who built many of the key Sultan’s buildings in Istanbul and around the empire. The Old Bridge stood for 427 years, until it was destroyed on 9 November 1993 by Croat military forces during the Croat–Bosniak War. Subsequently, a project was set in motion to reconstruct it; the rebuilt bridge opened on 23 July 2004.

One of the country's most recognizable landmarks, it is considered an exemplary piece of Balkan Islamic architecture. It was designed by Mimar Hayruddin, a student and apprentice of the famous architect Mimar Sinan.[2][3][4][5]

Characteristics

The bridge spans the Neretva river in the old town of Mostar, the city to which it gave the name. The city is the fifth-largest in the country; it is the center of the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the unofficial capital of Herzegovina. The Stari Most is hump-backed, 4 metres (13 ft 1 in) wide and 30 metres (98 ft 5 in) long, and dominates the river from a height of 24 m (78 ft 9 in). Two fortified towers protect it: the Halebija tower on the northeast and the Tara tower on the southwest, called "the bridge keepers" (natively mostari).[1]

The arch of the bridge was made of local stone known as tenelija. The shape of the arch is the result of numerous irregularities produced by the deformation of the intrados (the inner line of the arch). The most accurate description would be that it is a circle of which the centre is depressed in relation to the string course.[1]

Instead of foundations, the bridge has abutments of limestone linked to wing walls along the waterside cliffs. Measuring from the summer water level of 40.05 m (131 ft 5 in), abutments are erected to a height of 6.53 metres (21 ft 5 in), from which the arch springs to its high point. The start of the arch is emphasized by a molding 0.32 metres (1 ft 1 in) in height. The rise of the arch is 12.02 metres (39 ft 5 in).[1]

History

The original bridge was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1557 to replace an older wooden suspension bridge of dubious stability. Construction began in 1557 and took nine years: according to the inscription the bridge was completed in 974 AH, corresponding to the period between 19 July 1566 and 7 July 1567. Tour directors used to state that the bridge was held together with metal pins and mortar made from the protein of egg whites.[6] Little is known of the building of the bridge, and all that has been preserved in writing are memories and legends and the name of the builder, Mimar Hayruddin (student of Mimar Sinan, the Ottoman architect). Charged under pain of death to construct a bridge of such unprecedented dimensions, the architect reportedly prepared for his own funeral on the day the scaffolding was finally removed from the completed structure. Upon its completion it was the widest man-made arch in the world.

According to the 17th century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi, the name Mostar itself means "bridge-keeper." As Mostar's economic and administrative importance grew with the growing presence of Ottoman rule, the precarious wooden suspension bridge over the Neretva gorge required replacement. The old bridge on the river "...was made of wood and hung on chains," wrote the Ottoman geographer Katip Çelebi, and it "...swayed so much that people crossing it did so in mortal fear". In 1566, Mimar Hayruddin, a student of the great architect Sinan, designed Stari Most during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. The bridge was said to have cost 300,000 Drams (silver coins) to build. The two-year construction project was supervised by Karagoz Mehmet Bey, Sultan Suleiman's son-in-law and the patron of Mostar's most important mosque complex, called the Hadzi Mehmed Karadzozbeg Mosque.

The bridge, 28 meters long and 20 meters high (90' by 64'), quickly became a wonder in its own time. The famous traveler Evliya Çelebi wrote in the 17th century that: the bridge is like a rainbow arch soaring up to the skies, extending from one cliff to the other. ...I, a poor and miserable slave of Allah, have passed through 16 countries, but I have never seen such a high bridge. It is thrown from rock to rock as high as the sky.[7]

Destruction

The Old Bridge was destroyed on 9 November 1993 during the War in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After its destruction a temporary cable bridge was erected in its place.

Newspapers based in Sarajevo reported that more than 60 shells hit the bridge before it collapsed.[8] Croatian General Slobodan Praljak argues in his document "How the Old Bridge Was Destroyed"[9] that there was an explosive charge or mine placed at the center of the bridge underneath and detonated remotely in addition to the Shelling that caused the collapse. Most historians disagree and believe his research was trying to absolve his men and himself from crimes committed during the war[10]. He has since committed suicide by drinking poison after being convicted of war crimes[11].

After the destruction of the Stari Most, a spokesman for the Croats admitted that they deliberately destroyed it, claiming that it was of strategic importance.[12] Academics have argued that the bridge held little strategic value and that its shelling was an example of deliberate cultural property destruction. Andras Riedlmayer terms the destruction an act of "killing memory", in which evidence of a shared cultural heritage and peaceful co-existence were deliberately destroyed.[8]

Both sides of the city remained linked until the bridge's reconstruction by the Spanish and Portuguese military engineers assigned to the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) mission.

Reconstruction

After the end of the war, plans were raised to reconstruct the bridge. The World Bank, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the World Monuments Fund formed a coalition to oversee the reconstruction of the Stari Most and the historic city centre of Mostar.[13] Additional funding was provided by Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Croatia and the Council of Europe Development Bank, as well as the Bosnian government.[13] In October 1998, UNESCO established an international committee of experts to oversee the design and reconstruction work.[13] It was decided to build a bridge as similar as possible to the original, using the same technology and materials.[13] The bridge was re-built with local materials and Ottoman construction techniques by the Turkish company Er-Bu.[14] Tenelia stone from local quarries was used and Hungarian army divers recovered stones from the original bridge from the river below.[13] Reconstruction commenced on 7 June 2001. The reconstructed bridge was inaugurated on 23 July 2004, with the cost estimated to be 15.5 million US dollars.[13][1]

Diving

Stari Most diving is a traditional annual competition in diving organized every year in mid summer (end of July). It has taken place 477 times as of 2013.[15] It is traditional for the young men of the town to leap from the bridge into the Neretva. As the Neretva is very cold, this is a risky feat and requires skill and training, [16] though TripAdvisor has said tourists do dive as well.[17] In 1968 a formal diving competition was inaugurated and held every summer. The first person to jump from the bridge since it was re-opened was Enej Kelecija.[18]

Since 2015, Stari Most has been a tour stop in the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series.

In popular culture

- Song about the bridge's return titled "Stari" (English:"Old one") by Bosnian singer Tifa.

- Smrt Gospodina Goluže, a movie by Živko Nikolić.

- The album artwork for the album Mojot son e samo moj by SunS depicts a Mostar-like city with the Old Bridge in the background.

- The music video "Hajde Da Se Volimo" by Mali Princ contains footage of the destruction of the bridge.

- Bosnian popular music band Hari Mata Hari featured the reconstructed bridge in its official video for their Eurovision Song Contest 2006 song Lejla.

- Turkish rock band Bulutsuzluk Özlemi's 1996 song "Yaşamaya Mecbursun" (lit. 'You have to live') written about sorrow after the destruction of Stari Most.[19] With lyrics:

| Turkish lyrics | English translation |

|---|---|

|

|

Gallery

Stairs on the Old Bridge in Mostar

Stairs on the Old Bridge in Mostar West side entrance to the Old Bridge in Mostar

West side entrance to the Old Bridge in Mostar East side Tower of the Old Bridge in Mostar

East side Tower of the Old Bridge in Mostar View from the Old Bridge in Mostar

View from the Old Bridge in Mostar Composite image (continuous shot) of a tourist diving from the Stari Most in 2009

Composite image (continuous shot) of a tourist diving from the Stari Most in 2009 Street in the Old Town, Mostar

Street in the Old Town, Mostar

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Old Bridge (Stari Most) in Mostar - Commission to preserve national monuments". old.kons.gov.ba. Commision to preserve national monuments (KONS). 8 July 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ Balić, Smail (1973). Kultura Bošnjaka: Muslimanska Komponenta. Vienna. pp. 32–34. ISBN 9783412087920.

- ↑ Čišić, Husein. Razvitak i postanak grada Mostara. Štamparija Mostar. p. 22. ISBN 9789958910500.

- ↑ Stratton, Arthur (1972). Sinan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9780684125824.

- ↑ Jezernik, Božidar (1995). "Qudret Kemeri: A Bridge between Barbarity and Civilization". The Slavonic and East European Review. 73 (95): 470–484. JSTOR 4211861.

- ↑ "Croats destroy historic bridge". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World : Hearts and Stones". www.saudiaramcoworld.com.

- 1 2 Coward, Martin (2009). Urbicide: The Politics of Urban Destruction. London: Routledge. pp. 1–7. ISBN 0-415-46131-6.

- ↑ "Translated from Croatian". slobodanpraljak.com. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ "Slobodan Praljak: Defending Himself by Distorting History :: Balkan Insight". www.balkaninsight.com. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ CNN, Lauren Said-Moorhouse and Hilary McGann,. "Bosnian war criminal dies after swallowing poison in court". CNN. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ Borowitz, Albert (2005). Terrorism for self-glorification: the herostratos syndrome. Kent State University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-87338-818-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Armaly, Maha; Blasi, Carlo; Hannah, Lawrence (2004). "Stari Most: rebuilding more than a historic bridge in Mostar". Museum International. 56 (4): 6–17. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.2004.00044.x.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- ↑ "Mostar". Gradmostar.blogger.ba. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/nn9kz8/the-bridge-divers-of-bosnia

- ↑ https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/ShowUserReviews-g295388-d447578-r116994789-Old_Bridge_Stari_Most-Mostar_Herzegovina_Neretva_Canton.html

- ↑ "Chránený klenot" (in Slovak). Pluska. 15 Dec 2006.

- ↑ http://www.bulutsuzluk.com/Icerik.asp?s=icerik&id=16 Retrieved: 2014-11-20

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stari Most. |

- Rehabilitation Design of the Old Bridge of Mostar

- The Old Bridge / Stari Most - Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Live webcams from Stari most and the Old town. (mirror)