Southern French Gothic

_02.jpg)

Southern French Gothic (French: gothique méridional) is a specific style of Gothic architecture developed in the south of France. It arose in the early 13th century following the victory of the Catholic church over the Cathars, as the church sought to re-establish its authority in the region. It is simpler and less ornate than northern French Gothic, and differs also in that the construction material is typically brick rather than stone. In time the style came to influence secular buildings as well as churches, and spread beyond the area where Catharism had flourished.

Origins

During the rise of Catharism, the luxury of Roman Catholic Church was constantly criticized by the Cathar ecclesiastics. After the political eradication of the Cathar aristocracy during the Albigensian crusade (1209-1229), the clergy of southern France understood that after having won the war, it was necessary for them to win back the minds of the population. In addition to setting up the Medieval Inquisition, they adopted a more austere and uncluttered architectural style.[1]

Geographical area

Southern French Gothic, as its name suggests, is found in the southern part of France, mainly in the regions where Catharism had developed, and which were subjected to religious and military repression from the North. The reconquest by the Catholic hierarchy gave rise to the construction or reconstruction of many religious buildings, but also of secular ones. The regions concerned are therefore the current départements of the Haute-Garonne (Toulouse), the Tarn (Albi), the Tarn-et-Garonne (Montauban), the Ariège, the Gers, the Aude, the Pyrénées-Orientales, the Hérault, with instances in neighboring départements as well.

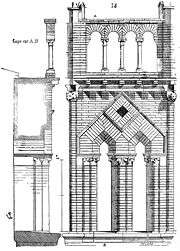

Characteristics

Southern French Gothic is characterized by the austerity of the constructions, such as the use of solid buttresses rather than flying buttresses, while the openings are few and narrow. Romanesque architecture persisted for longer in the south of France than in the north, and the transition to Gothic was progressive. Many of the buildings in the Southern Gothic style are thus built with a single nave, and are covered by roof-frames resting on diaphragm arches.

Brick construction

In an area poor in stone, the typical construction material was brick, whose use in the Southern French Gothic of the regions of Toulouse, Montauban, and Albi became one of its distinguishing marks. The builders used techniques adapted to this material, such as the mitre arches typical of this style. Brick lends itself to geometric decorative compositions, and consequently there are few sculptures integrated into the architecture. Depending on the type of clay used, the bricks can be molded or rounded by abrasion. Some buildings use stone sparingly to create colour contrasts.

Neighbouring regions coming under this influence but dominated by stone construction often adopted the same architectural vocabulary.

Single nave

After the Cathar episode, one goal of the Catholic church was the recovery of the faithful through preaching (hence the foundation by Dominique de Guzmán of the order of the Friars Preachers). To this end the preference was for the single nave, which promotes acoustics and places all the faithful under the gaze of the preacher. The nave is lined with side chapels, lodged between the buttresses, and surmounted by large windows that illuminate it.

However, the presence of a single nave is not necessarily related to this desire, but may be related to other considerationssuch as a single pre-existing nave. Conversely, the very wide nave of the Jacobins of Toulouse is divided by a row of pillars, but is nevertheless a single entity.

- Saint-Paul of Frontignan

- Saint-Fulcran of Lodève

Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais of Lectoure

Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais of Lectoure Church of the Jacobins of Toulouse

Church of the Jacobins of Toulouse

Bell tower

The bell towers can be of all types, but two forms emerge: the "Toulouse" bell tower, and the wall belfry.

Octagonal "Toulouse" bell tower

In the Toulouse region the typical bell tower appeared in the Romanesque period, octagonal floor plan gradually decreasing, smoothly passed to the Gothic only changing the shape of its bays. It is usually surmounted by a spire, but a certain number is missing, either because it was destroyed or because the construction was interrupted. The typical example is the bell tower of Saint-Sernin of Toulouse, enhanced in the Gothic period with mitre arches succeeding the Romanesque arched windows, but there are also bays ogive.

- Cordeliers of Toulouse

- Saint-Maurice of Mirepoix

Saint-Félix of Saint-Félix-Lauragais, made of stone

Saint-Félix of Saint-Félix-Lauragais, made of stone.jpg)

Saint-Pierre church of Blagnac

Saint-Pierre church of Blagnac

Wall belfry

The other form of bell tower, more common in smaller buildings, is the wall belfry, also frequently equipped with mitre arches and often having a fortification aspect (battlements, machicolations).

Saint-Paul church of Auterive

Saint-Paul church of Auterive Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption church of Villefranche-de-Lauragais

Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption church of Villefranche-de-Lauragais- Saint-André church of Montgiscard

Saint-Eutrope church of Miremont

Saint-Eutrope church of Miremont Sainte-Marie-Madeleine church of Pibrac

Sainte-Marie-Madeleine church of Pibrac

Fortification elements

Defensive elements are frequent: battlements, machicolations, walkways, watchtowers. Most of the time, except in cases where the church is included in a defensive system, these elements have only a decorative and especially symbolic role, tending to assert the power of the Church. At Notre-Dame de Simorre, Viollet-le-Duc added on his own a crenellation and watchtowers at the top of the buttresses.

Machicolations, Augustins of Toulouse

Machicolations, Augustins of Toulouse Machicolations, Saint-Alain of Lavaur

Machicolations, Saint-Alain of Lavaur Battlements and watchtowers, Église Notre-Dame of Simorre

Battlements and watchtowers, Église Notre-Dame of Simorre Saint-Nicolas of Toulouse

Saint-Nicolas of Toulouse

Civilian buildings

If the term "Southern French Gothic" is applied mainly to buildings of worship, churches and cathedrals, the principles of their architecture can be found in buildings used for other purposes: sobriety of the construction, absence or limitation of carved decoration, massive appearance, defense elements. One can mention in Toulouse the mansions, the Saint-Raymond College; in Albi, the Berbie Palace, etc ...

Photo gallery

Saint-Germain church of Alairac

Saint-Germain church of Alairac

_St-Andr%C3%A9.jpg) Saint-André of Montagnac (Hérault)

Saint-André of Montagnac (Hérault)

Sources

General books

- Collectif, Cahiers de Fanjeaux, No. 9, La naissance et l’essor du gothique méridional au XIIIs, Toulouse, 1974.

- Marcel Durliat, « L’architecture gothique méridionale au XIIIs », École antique de Nîmes, Bulletin annuel, Nouvelle série, No. 8-9, Nîmes, 1973-1974, p. 63-132.

- Yvette Carbonell-Lamothe, « Un gothique méridional ? », Midi, No. 2, 1987, p. 53-58.

Specialized books

- Jean-Louis Biget et Henri Pradalier, « L’art cistercien dans le Midi Toulousain », Cahiers de Fanjeaux, No. 21, Toulouse, 1986, p. 313-370.

- La cathédrale Sainte-Cécile, 1998, isbn=290947805X

- Henri Pradalier, « L’art médiéval dans le Midi Toulousain », Congrès archéologique de France. Monuments en Toulousain et Comminges (1996), 154e session, Société française d'archéologie, Paris, 2002, p. 11-17.

- Henri Pradalier, « Les rapports entre l’architecture civile et religieuse de Languedoc et d’Avignon sous les pontificats de Jean XXII et Benoît XII », Cahiers de Fanjeaux, 1991, p. 385-403.

- Maurice Prin, « Les Jacobins », Congrès archéologique de France. Monuments en Toulousain et Comminges (1996), 154e session, Société française d'archéologie, Paris, 2002, p. 177-187.

- Maurice Prin et Jean Dieuzaide, Les Jacobins de Toulouse. Regard et description, éd. Les Amis des Archives de la Haute-Garonne, Toulouse, 2007.

References

- ↑ fr:La cathédrale Sainte-Cécile, page 6