Crux

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Cru |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Crucis |

| Pronunciation | /krʌks/, genitive /ˈkruːsɪs/ |

| Symbolism | Southern Cross |

| Right ascension | 12.5h |

| Declination | −60° |

| Quadrant | SQ3 |

| Area | 68 sq. deg. (88th) |

| Main stars | 4 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 19 |

| Stars with planets | 2 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 5 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | Acrux (α Cru) (0.87m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | Crucids |

| Bordering constellations |

Centaurus Musca |

|

Visible at latitudes between +20° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of May. | |

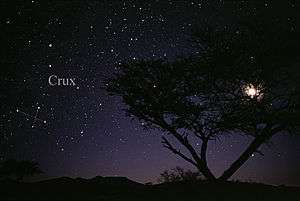

Crux /krʌks/ is a constellation located in the southern sky in a bright portion of the Milky Way. It is among the most easily distinguished constellations, as all of its four main stars have an apparent visual magnitude brighter than +2.8, even though it is the smallest of all 88 modern constellations. Its name is Latin for cross, and it is dominated by a cross-shaped or kite-like asterism that is commonly known as the Southern Cross.

Predominating is the first-magnitude blue-white star of Alpha Crucis or Acrux, being the constellation's brightest and most southerly member. Crux is followed by four dominant stars, descending in clockwise order by magnitude: Beta, Gamma (one of the closest red giants to Earth), Delta and Epsilon Crucis. Many of these brighter stars are members of the Scorpius–Centaurus Association, a large but loose group of hot blue-white stars that appear to share common origins and motion across the southern Milky Way. The constellation contains four Cepheid variables that are each visible to the naked eye under optimum conditions. Crux also contains the bright and colourful open cluster known as the Jewel Box (NGC 4755) and, to the southwest, partly includes the extensive dark nebula, known as the Coalsack Nebula.

History

The stars within Crux were known to the Ancient Greeks, where Ptolemy regarded them as part of the constellation Centaurus.[1][2] They were entirely visible as far north as Britain in the fourth millennium BC. However, the precession of the equinoxes gradually lowered the stars below the European horizon, and they were eventually forgotten by the inhabitants of northern latitudes.[3] By AD 400, most of the stars in the constellation we now call Crux never rose above the horizon for Athenians.

The 15th-century Venetian navigator Alvise Cadamosto made note of what was probably the Southern Cross on exiting the Gambia River in 1455, calling it the carro dell'ostro ("southern chariot"). However, Cadamosto's accompanying diagram was inaccurate.[4][5] Historians generally credit João Faras – astronomer and physician of King Manuel I of Portugal who accompanied Pedro Álvares Cabral in the discovery of Brazil in 1500 – for being the first European to depict it correctly. Faras sketched and described the constellation (calling it "Las Guardas") in a letter written on the beaches of Brazil on May 1, 1500, to the Portuguese monarch.[6][7]

Explorer Amerigo Vespucci seems to have observed not only the Southern Cross but also the neighboring Coalsack Nebula on his second voyage in 1501–02.[8]

Another early modern description clearly describing Crux as a separate constellation is attributed to Andreas Corsali, an Italian navigator who from 1515 to 1517 sailed to China and the East Indies in an expedition sponsored by King Manuel I. In 1516, Corsali wrote a letter to the monarch describing his observations of the southern sky, which included a rather crude map of the stars around the south celestial pole including the Southern Cross and the two Magellanic Clouds seen in an external orientation, as on a globe.[9][10]

Emery Molyneux and Petrus Plancius have also been cited as the first uranographers to distinguish Crux as a separate constellation; their representations date from 1592, the former depicting it on his celestial globe and the latter in one of the small celestial maps on his large wall map. Both authors, however, depended on unreliable sources and placed Crux in the wrong position. Crux was first shown in its correct position on the celestial globes of Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius in 1598 and 1600. Its stars were first catalogued separately from Centaurus by Frederick de Houtman in 1603.[11] Later adopters of the constellation included Jakob Bartsch in 1624 and Augustin Royer in 1679. Royer is sometimes wrongly cited as initially distinguishing Crux.[12]

Characteristics

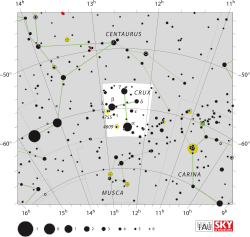

Crux is bordered by the constellations Centaurus (which surrounds it on three sides) on the east, north and west, and Musca to the south. Covering 68 square degrees and 0.165% of the night sky, it is the smallest of the 88 constellations.[13] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'Cru'.[14] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of four segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 11h 56.13m and 12h 57.45m, while the declination coordinates are between −55.68° and −64.70°.[15] The whole constellation is visible to observers south of latitude 25°N.[16][lower-alpha 1]

In tropical regions Crux can be seen in the sky from April to June. Crux is exactly opposite to Cassiopeia on the celestial sphere, and therefore it cannot appear in the sky with the latter at the same time. For locations south of 34°S, Crux is circumpolar and thus always visible in the night sky.

Crux is sometimes confused with the nearby False Cross by stargazers. Crux is somewhat kite-shaped (a Latin cross), and it has a fifth star (ε Crucis). The False Cross is diamond-shaped (a Greek cross), somewhat dimmer on average, does not have a fifth star and lacks the two prominent nearby "Pointer Stars".

Visibility

Crux is easily visible from the southern hemisphere at practically any time of year. It is also visible near the horizon from tropical latitudes of the northern hemisphere for a few hours every night during the northern winter and spring. For instance, it is visible from Cancun or any other place at latitude 25° N or less at around 10 pm at the end of April.[17][18] There are 5 main stars. Due to precession, Crux will move closer to the South Pole in the next millennia, up to 67 degrees south declination for the middle of the constellation. But in AD 18000 or BC 8000 Crux will be and was less than 30 degrees south declination making it visible in Northern Europe. Even by AD 14000, it will be visible for most parts of Europe and the whole United States.

Use in navigation

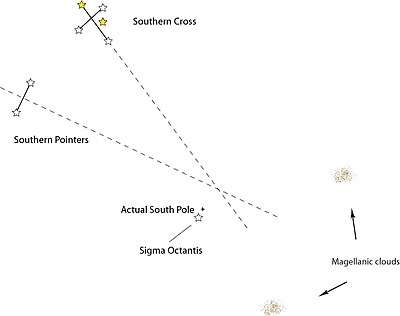

In the Southern Hemisphere, the Southern Cross is frequently used for navigation in much the same way that Polaris is used in the Northern Hemisphere. Alpha and Gamma (known as Acrux and Gacrux, respectively) are commonly used to mark south. Tracing a line from Gacrux to Acrux leads to a point close to the Southern Celestial Pole.[3] Alternatively, if a line is constructed perpendicularly between Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri, the point where the above-mentioned line and this line intersect marks the Southern Celestial Pole. Another way to find south, strike line through Gacrux and Acrux, 4 1/2 times the distance between Gacrux and Acrux, directly below that point is south. The two stars of Alpha and Beta Centauri are often referred to as the "Southern Pointers" or just "The Pointers", allowing people to easily find the asterism of the Southern Cross or the constellation of Crux. Very few bright stars of importance lie between Crux and the pole itself, although the constellation Musca is fairly easily recognised immediately beneath Crux.[19]

A technique used in the field is to clench one's right fist and to view the cross, aligning the first knuckle with the axis of the cross. The tip of the thumb will indicate south.[19]

Argentine gauchos are well known for using it for night orientation in the vast Pampas and Patagonic regions.

Features

Stars

Within the constellation's borders, there are 49 stars brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[lower-alpha 2][16] The four main stars that form the asterism are Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta Crucis. Also known as Acrux, Alpha Crucis is a triple star 321 light-years from Earth. Blue-tinged and magnitude 0.8 to the unaided eye, it has two close components of magnitude 1.3 and 1.8, as well as a wide component of magnitude 5. The two close components are resolved in a small amateur telescope and the wide component is readily visible in a pair of binoculars. Beta Crucis, called Mimosa, is a blue-hued giant of magnitude 1.3, 353 light-years from Earth. It is a Beta Cephei-type Cepheid variable with a variation of less than 0.1 magnitudes.[3] Gamma Crucis, called Gacrux, is an optical double star. The primary is a red-hued giant star of magnitude 1.6, 88 light-years from Earth. The secondary is of magnitude 6.5, 264 light-years from Earth. Delta Crucis (the proper name is Imai[21]) is a blue-white hued star of magnitude 2.8, 345 light-years from Earth. It is the dimmest of the Southern Cross stars.[3] Like Beta it is a Beta Cepheid.[13]

There are several dimmer stars within the borders of Crux. Epsilon Crucis (Ginan[22]) is an orange-hued giant star of magnitude 3.6, 228 light-years from Earth. Iota Crucis is a binary star 125 light-years from Earth. The primary is an orange-hued giant of magnitude 4.6 and the secondary is of magnitude 9.5. Mu Crucis is a double star where the unrelated components are about 370 light-years from Earth. The primary is a blue-white hued star of magnitude 4.0 and the secondary is a blue-white hued star of magnitude 5.1. Mu Crucis is divisible in small amateur telescopes or large binoculars.[3]

15 of the 23 brightest stars are blue-white B-type stars.[13] Of the five main cross stars, Delta Crucis and probably Acrux and Mimosa are co-moving B-type members of the Scorpius–Centaurus Association, the nearest OB association to the Sun.[23][24] They are among the highest-mass stellar members of the Lower Centaurus-Crux subgroup of the association, with ages of roughly 10 to 20 million years.[25][26] Other members include the blue-white stars Zeta, Lambda, Mu1 and Mu2.[27]

Lambda Crucis and Theta2 Crucis are also Beta Cepheid stars.[13]

Crux boasts four Cepheid variables that reach naked eye visibility. BG Crucis ranges from magnitude 5.34 to 5.58 over 3.3428 days,[28] T Crucis ranges from 6.32 to 6.83 over 6.73331 days,[29] S Crucis ranges from 6.22 to 6.92 over 4.68997 days,[30] and R Crucis ranges from 6.4 to 7.23 over 5.82575 days.[31] BH Crucis, also known as Welch's Red Variable, is a Mira variable that ranges from magnitude 6.6 to 9.8 over 530 days.[32] Discovered in October 1969, it has become redder and brighter (mean magnitude changing from 8.047 to 7.762) and its period lengthened by 25% in the first thirty years since its discovery.[33]

The star HD 106906 has been found to have a planet—HD 106906 b—that has a larger orbit than any other exoplanet discovered to date.

Deep-sky objects

The Coalsack Nebula is the most prominent dark nebula in the skies, easily visible to the naked eye as a prominent dark patch in the southern Milky Way. It is large, five degrees by seven degrees, and is 600 light-years from Earth. Not all of the nebula is in the borders of Crux; some of it is technically in Musca and Centaurus.[3]

The open cluster NGC 4755, better known as the Jewel Box or Crucis Cluster, has an overall magnitude of 4.2—to the naked eye it appears to be a fuzzy star—and is about 6400 light-years from Earth.[3] The cluster was given its name by John Herschel.[3] About seven million years old, an age that makes it one of the youngest open clusters in the Milky Way, it appears to have the shape of a letter A. The Jewel Box Clusters is a Shapley class g and Trumpler class I 3 r cluster; it is a very rich, centrally-concentrated cluster detached from the surrounding star field. It has more than 100 stars that range significantly in brightness.[34] The brightest stars are mostly blue supergiants, though the cluster contains a few bright red supergiants. Kappa Crucis is a true member of the cluster that bears its name, and is one of the brighter stars at magnitude 5.9.[3]

Cultural significance

The most prominent feature of Crux is the distinctive asterism known as the Southern Cross. It has great significance in the cultures of the southern hemisphere, particularly of Australia and New Zealand.[35]

Southern Cross is the name of a single released by Crosby, Stills and Nash in 1981. It reached #18 on Billboard Hot 100 in late 1982.

Flags and symbols

Several southern countries and organisations have traditionally used Crux as a national or distinctive symbol. The four or five brightest stars of Crux appear, heraldically standardised in various ways, on the flags of Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Samoa. They also appear on the flags of the Australian state of Victoria, the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory, as well as the flag of Magallanes Region of Chile, the flag of Londrina (Brazil) and several Argentine provincial flags and emblems (for example, Tierra del Fuego and Santa Cruz). The flag of the Mercosur trading zone displays the four brightest stars. Crux also appears on the Brazilian coat of arms and, as of July 2015, on Brazilian passports.

A Cross also gets a mention in the lyrics of the Brazilian National Anthem (1909): "A imagem do Cruzeiro resplandece" ("the image of the Cross shines"). Five stars appear in the logo of the Brazilian football team Cruzeiro Esporte Clube and in the Brazilian coat of arms, and the cross has featured as name of the Brazilian currency (the cruzeiro from 1942 to 1986 and again from 1990 to 1994). All coins of the current (1998) series of the Brazilian real display the constellation.

Songs and literature reference the Southern Cross, including the Argentine epic poem Martín Fierro. The Argentinian singer Charly García says that he is "from the Southern Cross" in the song "No voy en tren".

The Order of the Southern Cross is a Brazilian order of chivalry awarded to "those who have rendered significant service to the Brazilian nation".

In "O Sweet Saint Martin's Land", the lyrics mention the Southern Cross: Thy Southern Cross the night.

A stylized version of Crux appears on the Australian Eureka Flag. The constellation was also used on the dark blue, shield-like patch worn by personnel of the U.S. Army's Americal Division, which was organized in the Southern Hemisphere, on the island of New Caledonia, and also on the blue diamond of the U.S. 1st Marine Division, which fought on the Southern Hemisphere islands of Guadalcanal and New Britain.

The Petersflagge flag of the German East Africa Company of 1885–1920, which included a constellation of five white five-pointed Crux "stars" on a red ground, later served as the model for symbolism associated with generic German colonial-oriented organisations: the Reichskolonialbund of 1936–1943 and the Friends of the former German Protectorates (1956/1983 to the present).

Southern Cross station is a major rail terminal in Melbourne, Australia.[36]

In non-Western astronomy

In Australian Aboriginal astronomy, Crux and the Coalsack mark the head of the 'Emu in the Sky' (which is seen in the dark spaces rather than in the patterns of stars) in several Aboriginal cultures,[37] while Crux itself is said to be a possum sitting in a tree (Boorong people of the Wimmera region of northwestern Victoria), a representation of the sky deity Mirrabooka (Quandamooka people of Stradbroke Island), a stingray (Yolngu people of Arnhem Land), or an eagle (Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains).[38] Two Pacific constellations also included Gamma Centauri. Torres Strait Islanders in modern-day Australia saw Gamma Centauri as the handle and the four stars as the trident of Tagai's Fishing Spear. The Aranda people of central Australia saw the four Cross stars as the talon of an eagle and Gamma Centauri as its leg.[39]

Various peoples in the East Indies and Brazil viewed the four main stars as the body of a ray.[39] In both Indonesia and Malaysia, it is known as Bintang Pari and Buruj Pari respectively ("ray stars")

The Javanese people of Indonesia called this constellation Gubug pèncèng ("raking hut") or lumbung ("the granary"), because the shape of the constellation was like that of a raking hut.[40]

The Māori name for the Southern Cross is Te Punga ("the anchor"). It is thought of as the anchor of Tama-rereti's waka (the Milky Way), while the Pointers are its rope.[41] In Tonga it is known as Toloa ("duck"); it is depicted as a duck flying south, with one of his wings (δ Crucis) wounded because Ongo tangata ("two men", α and β Centauri) threw a stone at it. The Coalsack is known as Humu (the "triggerfish"), because of its shape.[42] In Samoa the constellation is called Sumu ("triggerfish") because of its rhomboid shape, while α and β Centauri are called Luatagata (Two Men), just as they are in Tonga. The peoples of the Solomon Islands saw several figures in the Southern Cross. These included a knee protector and a net used to catch Palolo worms. Neighboring peoples in the Marshall Islands saw these stars as a fish.[39]

In Mapudungun, the language of Patagonian Mapuches, the name of the Southern Cross is Melipal, which means "four stars". In Quechua, the language of the Inca civilization, Crux is known as "Chakana", which means literally "stair" (chaka, bridge, link; hanan, high, above), but carries a deep symbolism within Quechua mysticism.[43] Acrux and Mimosa make up one foot of the Great Rhea, a constellation encompassing Centaurus and Circinus along with the two bright stars. The Great Rhea was a constellation of the Bororo of Brazil. The Mocoví people of Argentina also saw a rhea including the stars of Crux. Their rhea is attacked by two dogs, represented by bright stars in Centaurus and Circinus. The dogs' heads are marked by Alpha and Beta Centauri. The rhea's body is marked by the four main stars of Crux, while its head is Gamma Centauri and its feet are the bright stars of Musca.[44] The Bakairi people of Brazil had a sprawling constellation representing a bird snare. It included the bright stars of Crux, the southern part of Centaurus, Circinus, at least one star in Lupus, the bright stars of Musca, Beta and Delta Chamaeleonis, Volans, and Mensa.[45] The Kalapalo people of Mato Grosso state in Brazil saw the stars of Crux as Aganagi angry bees having emerged from the Coalsack, which they saw as the beehive.[46]

Among Tuaregs, the four most visible stars of Crux are considered iggaren, i.e. four Maerua crassifolia trees. The Tswana people of Botswana saw the constellation as Dithutlwa, two giraffes – Acrux and Mimosa forming a male, and Gacrux and Delta Crucis forming the female.[47]

See also

Notes

- ↑ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between 25°N and 34°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[16]

- ↑ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[20]

References

- Citations

- ↑ Pasachoff, Stars and Planets, 2006, p. 144.

- ↑ Staal, , 1998, p. 247

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ "We likewise observed...due south by compass, a constellation of six large bright stars, in the figure of a cross in this form...we conjectured this to be the southern chariot, but could not expect to observe the principal star, as we had not yet lost sight of the north pole." A. Cadamosto Navigatione, written c.1465 (1550 Ramusio edition, p.116r; 1811 Kerr edition p.244). However, note a manuscript of Cadamosto's notebook has not survived, only the printed version, and the errors in the diagram may be due to the printer's decision.

- ↑ Dekker, Elly (1990). Annals of Science, vol. 47, pp. 530–533.

- ↑ Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, V nº 19., Rio de Janeiro, 1843

- ↑ Dekker, Elly (1990). Annals of Science, vol. 47, pp. 533–535.

- ↑ Dekker, Elly (1990). Annals of Science, vol. 47, pp. 535–543.

- ↑ Dekker, Elly (1990). Annals of Science, vol. 47, pp. 545–548.

- ↑ "Letter to Giuliano de Medici, c.1516". State Library NSW. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ↑ "Ian Ridpath's Star Tales – Crux". Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ↑ Staal 1988, p. 247.

- 1 2 3 4 Bagnall, Philip M. (2012). The Star Atlas Companion: What You Need to Know about the Constellations. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 183–87. ISBN 978-1-4614-0830-7.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ "Crux, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ian Ridpath. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Pasachoff, Jay M (2000). Field Guide to the Stars and Planets. Houghton Miflin. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-395-93431-9.

- ↑ "Ian Ridpath.com: Constellations". Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- 1 2 Grainger, DH. Don't die in the Bundu (8th ed.). Cape Town. pp. 84–86. ISBN 0 86978 056 5.

- ↑ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ↑ "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Preibisch, T.; Mamajek, E. (2008). "The Nearest OB Association: Scorpius-Centaurus (Sco OB2)". Handbook of Star-Forming Regions. 2: 0. arXiv:0809.0407. Bibcode:2008hsf2.book..235P.

- ↑ Rizzuto, Aaron; Ireland, Michael; Robertson, J. G. (October 2011), "Multidimensional Bayesian membership analysis of the Sco OB2 moving group", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 416 (4): 3108–3117, arXiv:1106.2857, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.416.3108R, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19256.x.

- ↑ de Geus, E. J.; de Zeeuw, P. T. & Lub, J. (1989). "Physical Parameters of Stars in the Scorpio-Centaurus OB Association". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 216 (3): 44–61. Bibcode:1989A&A...216...44D.

- ↑ Mamajek, E.E.; Meyer, M.R.; Liebert, J. (2002). "Post-T Tauri Stars in the Nearest OB Association". Astronomical Journal. 124 (3): 1670–1694. arXiv:astro-ph/0205417. Bibcode:2002AJ....124.1670M. doi:10.1086/341952.

- ↑ de Zeeuw, P.T.; Hoogerwerf, R.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Brown, A.G.A.; Blaauw, A. (1999). "A Hipparcos Census of Nearby OB Associations". Astronomical Journal. 117 (1): 354–99. arXiv:astro-ph/9809227. Bibcode:1999AJ....117..354D. doi:10.1086/300682.

- ↑ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "BG Crucis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "T Crucis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "S Crucis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "R Crucis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Otero, Sebastian (6 January 2011). "BH Crucis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Walker, W.S.G. (2009). "BH Crucis : Period, Magnitude, and Color Changes". J. Am. Assoc. Variable star obs. 37: 87–95. Bibcode:2009JAVSO..37...87W.

- ↑ Levy 2005, p. 87.

- ↑ "Story: Southern Cross".

- ↑ "Southern Cross Railway Station, Victoria – Railway Technology". Railway Technology. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- ↑ Norris, R. (2007): The Emu in the Sky Australian Aboriginal Astronomy website. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ↑ Musgrave, I.: May sky guide: The Eta Aquarid meteor shower, constellations and planets ABC News, 2 May 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Staal 1988, p. 249.

- ↑ Daldjoeni, N. (1984). "Pranatamangsa, the javanese agricultural calendar – Its bioclimatological and sociocultural function in developing rural life". The Environmentalist. 4: 15–18. doi:10.1007/BF01907286.

- ↑ "Māori Dictionary; Waka o Tama-rereti, Te". Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Velt 1990.

- ↑ "Chakana: Inca Cross". 23 June 2007. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Staal 1988, p. 251.

- ↑ Staal 1988, p. 250.

- ↑ Basso, Ellen B. (1987). In Favor of Deceit: A Study of Tricksters in an Amazonian Society. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 360. ISBN 0816510229.

- ↑ Clegg, Andrew (1986). "Some Aspects of Tswana Cosmology". Botswana Notes and Records. 18: 33–37. JSTOR 40979758.

- Sources

- Levy, David H. (2005), Deep Sky Objects, Prometheus Books, ISBN 1-59102-361-0

- Pasachoff, Jay M. (2006), A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, Houghton Mifflin

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691177885

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988), The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars, McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, ISBN 0939923041

- Velt, Kik (1990), Stars Over Tonga, 'Atenisi University

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Finding the South Pole in the sky

- Southern Cross in Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Andrea Corsali – Letter to Giuliano de Medici, 1516 showing the Southern Cross at the State Library of NSW

- Letter of Andrea Corsali 1516–1989: with additional material ("the first description and illustration of the Southern Cross, with speculations about Australia ...") digitised by the National Library of Australia.