Sagitta

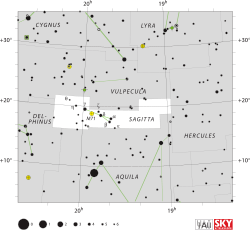

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Sge |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Sagittae |

| Pronunciation |

/səˈdʒɪtə/ Sagítta, genitive /səˈdʒɪtiː/ |

| Symbolism | the Arrow |

| Right ascension | 19.8333h |

| Declination | +18.66° |

| Quadrant | NQ4 |

| Area | 80 sq. deg. (86th) |

| Main stars | 4 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 19 |

| Stars with planets | 2 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 1 |

| Brightest star | γ Sge (3.51m) |

| Messier objects | 1 |

| Bordering constellations |

Vulpecula Hercules Aquila Delphinus |

|

Visible at latitudes between +90° and −70°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of August. | |

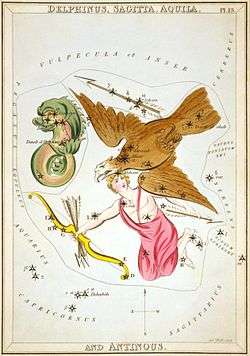

Sagitta is a dim but distinctive constellation in the northern sky. Its name is Latin for "arrow", and it should not be confused with the significantly larger constellation Sagittarius, the archer. Although Sagitta is an ancient constellation, it has no star brighter than 3rd magnitude and has the third-smallest area of all constellations (only Equuleus and Crux are smaller). It was included among the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations defined by the International Astronomical Union. Located to the north of the equator, Sagitta can be seen from every location on Earth except within the Antarctic circle.

The red giant Gamma Sagittae is the constellation's brightest star, with an apparent magnitude of 3.47. Two star systems have been found to have planets.

History

The Greeks who may have[1] originally identified this constellation called it Oistos.[2] The Romans named it Sagitta.[3] Sagitta's shape is reminiscent of an arrow, and many cultures have interpreted it thus, among them the Persians, Hebrews, Greeks and Romans. The Arabs called it as-Sahm, a name that was transferred Sham and now refers to Alpha Sagittae only.

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, Sagitta was regarded as the weapon that Hercules used to kill the eagle (Aquila) of Jove that perpetually gnawed Prometheus' liver.[4] The Arrow is located beyond the north border of Aquila, the Eagle. According to R.H. Allen, the Arrow could be the one shot by Hercules towards the adjacent Stymphalian birds (6th labor) who had claws, beaks and wings of iron, and who lived on human flesh in the marshes of Arcadia - Aquila the Eagle, Cygnus the Swan, and Lyra (the Vulture) - and still lying between them, whence the title Herculea (although Allen cites no reference to support this assertion).[5] Eratosthenes claimed it as the arrow with which Apollo exterminated the Cyclopes.[4]

Characteristics

Covering 79.9 square degrees and hence 0.194% of the sky, Sagitta ranks 86th of the 88 modern constellations by area.[6] Its position in the Northern Celestial Hemisphere means that the whole constellation is visible to observers north of 69°S.[6][lower-alpha 1] It is bordered by Vulpecula to the north, Hercules to the west, Aquila to the south, and Delphinus to the east. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'Sge'.[7] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of twelve segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 18h 57.2m and 20h 20.5m, while the declination coordinates are between 16.08° and 21.64°.[8]

Notable features

Stars

Johann Bayer gave Bayer designations to eight stars, labelling them Alpha to Theta. What was viewed by Bayer, Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander and Heis as a single star Theta was in fact three stars, and is now equated to HR 7705. John Flamsteed added the letters x (mistaken as Chi), y and z to 13, 14 and 15 Sagittae in his Catalogus Britannicus. All three were dropped by Bevis and Baily.[9]

In his Uranometria, Bayer depicted Alpha, Beta and Epsilon Sagittae as the fins of the arrow.[10] Also known as Sham, Alpha is a yellow bright giant star of spectral class G1 II (with an apparent magnitude of 4.38, which lies at a distance of 430 ± 10 light-years from Earth.[11] Originally 4 times as massive as the Sun, it has swollen and brightened to 20 times its diameter and 340 times its luminosity.[12] Also of magnitude 4.38, Beta is a G-type giant located 440 ± 20 light-years distant from Earth.[11] Epsilon Sagittae is G8 III, 5.66m, multiple star (4 components; component B is optical)

Ptolemy saw the constellation's brightest star Gamma Sagittae as marking the arrow's head,[13] while Bayer saw Gamma, Eta and Theta as depicting the arrow's shaft.[10] Gamma Sagittae is a red giant of spectral type M0III, and magnitude 3.47. It lies at a distance of 258 ± 4 light-years from Earth.[11] Eta Sagittae is a star of spectral class K2 III with a magnitude of 5.1, which belongs to the Hyades Stream. Theta Sagittae is a multiple star system.

Delta and Zeta depicted the spike according to Bayer.[10] Delta Sagittae is a suspected visual double - M2 II+A0 V probably single image, composite spectrum), magnitude 3.82. Zeta Sagittae is a triple system, approximately 326 light-years from Earth, the primary an A-type star.

FG Sagittae is a remote highly luminous star around 8000 light years distant from Earth. WR 124 is a Wolf-Rayet star moving at great speed surrounded by a nebula of ejected gas. HD 183143 is a remote blue-white star that has been described as a blue supergiant or hypergiant. It is an Alpha Cygni variable.

R Sagittae is a member of the rare RV Tauri variable class of star. It ranges in magnitude from 8.2 to 10.4. [14]

S Sagittae is a Classical Cepheid variable that varies from magnitude 5.24 to 6.04 in 8.38 days. It is a yellow-white supergiant that varies between spectral types F6Ib and G5Ib.[15] Around 6 or 7 times as massive and 3500 time as luminous as the Sun, it is located around 2300 light-years away from Earth.[16]

Located near 18 Sagittae is V Sagittae, the prototype of the V Sagittae variables, cataclysmic variables that are also super soft X-ray source.[14]

WZ Sagittae is a dwarf nova composed of a white dwarf and low mass star companion. The black widow pulsar (B1957+20) is a millisecond pulsar with a brown dwarf companion.

HD 231701 is a yellow-white main sequence star hotter and larger than our Sun, which was found to have a planet in 2007. 15 Sagittae is a solar analog that has a brown dwarf substellar companion.

Deep-sky objects

Messier 71 is a very loose globular cluster mistaken for quite some time for a dense open cluster. It lies at a distance of about 13,000 light-years from Earth and was first discovered by the French astronomer Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in the year 1745 or 1746.

Notes

References

- ↑ page 88 in Origins of the ancient constellations: II. The Mediterranean traditions, by J. H. Rogers 1998

- ↑ Katasterismoi per theoi.com in theoi.com

- ↑ M., Bagnall, Philip (2012). The star atlas companion : what you need to know about the constellations. Springer. ISBN 9781461408307. OCLC 794225463.

- 1 2 Astronomica by Hyginus, Mary Grant translation at theoi.com

- ↑ Allen, Richard H.; Star Names — Their Lore and Meaning (1899), Dover Pubs, 1963, page 350 ( ISBN 0-486-21079-0).

- 1 2 3 Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ "Sagitta, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Wagman 2003, pp. 266–67.

- 1 2 3 Wagman 2003, p. 515.

- 1 2 3 van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- ↑ Kaler, James B. "Sham". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Sagitta". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- 1 2 Levy, David H. (1998). Observing Variable Stars: A Guide for the Beginner. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–53. ISBN 978-0-521-62755-9.

- ↑ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "S Sagittae". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Kaler, James B. (4 October 2013). "S Sagittae". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

Cited texts

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

External links

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Sagitta

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (over 120 medieval and early modern images of Sagitta)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sagitta. |