Tswana people

_by_The_London_Missionary_Society_cropped.jpg) A congregation of Tswana people with David Livingstone, an illustration created by the London Missionary Society circa 1900 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 1.61 million[1] | |

| 4,067,248 (Tswana-speakers)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Setswana language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African Traditional Religion. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| The Sotho, The Northern Sotho, The Bakgalagari | |

| Person | Motswana |

|---|---|

| People | Batswana |

| Language | Setswana |

| Country | Botswana |

The Tswana (Tswana: Batswana, singular Motswana) are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group who are native to Southern Africa. The Tswana language belongs to the Bantu group. Ethnic Tswana made up approximately 85% of the population of Botswana in 2011.[1]

In the nineteenth century, a common spelling and pronunciation of Batswana was Bechuana. Europeans therefore referred to the area largely inhabited by the Tswana as Bechuanaland. In the Tswana language, however, Botswana is the name for the country of the Tswana.

Early History of Batswana

The Batswana are descended mainly from Bantu-speaking tribes who migrated southward into the region 1500 years ago, living in tribal enclaves as farmers and herders. Several Iron Age cultures flourished from around 900 AD, with the Toutswe, based in the eastern region of what is now Botswana, relying on cattle held in kraals as their source of wealth. The arrival of the ancestors of the Tswana-speakers who came to control the region (from the Vaal River to Botswana) has yet to be dated precisely although AD 600 seems to be a consensus estimate. This massive cattle-raising complex prospered until 1300 AD or so. All these various peoples were connected to trade routes that ran via the Limpopo River to the Indian Ocean, and trade goods from Asia such as beads made their way to Botswana most likely in exchange for ivory, gold, and rhinoceros horn. Members of the Bakwena, a chieftaincy under a legendary leader named Kgabo II, made their way into the southern Kalahari by AD 1500, at the latest, and his people drove the Bakgalagadi inhabitants west into the desert. Over the years, several offshoots of the Bakwena moved into adjoining territories. The Bangwaketse occupied areas to the west, while the Bangwato moved northeast into formerly Bakalanga areas. Not long afterwards, a Bangwato offshoot known as the Batawana migrated into the Okavango Delta, probably in the 1790s. The first written records relating to modern-day Botswana appear in 1824. What these records show is that the Bangwaketse had become the predominant power in the region. Under the rule of Makaba II, the Bangwaketse kept vast herds of cattle in well-protected desert areas, and used their military prowess to raid their neighbours. Other chiefdoms in the area, by this time, had capitals of 10,000 or so and were fairly prosperous. This equilibrium came to end during the Mfecane period, 1823-1843, when a succession of invading peoples from South Africa entered the country. Although the Bangwaketse were able to defeat the invading Bakololo in 1826, over time all the major chiefdoms in Botswana were attacked, weakened, and impoverished. The Bakololo and Amandebele raided repeatedly, and took large numbers of cattle, women, and children from the Batswana—most of whom were driven into the desert or sanctuary areas such as hilltops and caves. Only after 1843, when the Amandebele moved into western Zimbabwe, did this threat subside.[3][4]

Dynasties and tribes

Botswana

The republic of Botswana (formerly the British protectorate of Bechuanaland) is named for the Tswana people. The country's eight major tribes speak Tswana, which is also called Setswana. All have a traditional Paramount Chief, styled Kgosikgolo, who is entitled to a seat in the Ntlo ya Dikgosi (an advisory body to the country's Parliament). The Tswana dynasties are all related. A person who lives in Botswana is a Motswana and the plural is Batswana.[5][6]

The three main branches of the Tswana tribe formed during the 17th century. Three brothers, Kwena, Ngwaketse and Ngwato, broke away from their father, Chief Molope, to establish their own tribes in Molepolole, Kanye and Serowe, probably in response to drought and expanding populations in search of pasture and arable land.[7]

The principal Tswana tribes are the:

- Kgatla tribe Bakgatla

- Bakwena

- Balete

- Bangwato

- BaNgwaketse tribe

- Barolong

- Batawana

- Batlhaping

- Batlase

South Africa

The largest number of ethnic Tswana people actually live in South Africa. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in the country, and the Tswana language is one of eleven official languages in South Africa. There were over 4 million Tswana speakers in the country in 2012,[2] with North West Province having a majority of 2,200,000 Tswana speakers. From 1948 to 1994, South African Tswana people were defined by the Apartheid regime to be citizens of Bophuthatswana, one of ten bantustans set up for the purpose of defending the policy of denying black Africans citizenship in South Africa.

Batswana-Boer Wars

During the 1840s and 1850s trade with Cape Colony-based merchants opened up and enabled the Batswana chiefdoms to rebuild. The Bakwena, Bangwaketse, Bangwato and Batawana cooperated to control the lucrative ivory trade, and then used the proceeds to import horses and guns, which in turn enabled them to establish control over what is now Botswana. This process was largely complete by 1880, and thus the Bushmen, the Bakalanga, the Bakgalagadi, the Batswapong and other current minorities were subjugated by the Batswana.

Following the Great Trek, Afrikaners from the Cape Colony established themselves on the borders of Botswana in the Transvaal. In 1852 a coalition of Tswana chiefdoms led by Sechele I

resisted Afrikaner incursions, and after about eight years of intermittent tensions and hostilities, eventually came to a peace agreement in Potchefstroom in 1860. From that point on, the modern-day border between South Africa and Botswana was agreed on, and the Afrikaners and Batswana traded and worked together peacefully.[8]

Battle of Dimawe

The Battle of Dimawe was the pivotal showdown in the Batswana-Boer War of 1852-53. During the conflict a coalition of merafe [Bakwena, Bangwaketse, Bangwato, Bakaa, Balete, Barolong, Bakgatla bagaMmanaana, Bahurutshe, and Batlokwa] united under Sechele's leadership in a seven-month armed struggle against the Transvaal Boers. Although the Boers began the hostilities, by invading south-eastern Botswana, it was they who ended up on the defensive. The Boer commando of just over 1,000 arrived at Dimawe on Saturday the 28th of August 1852. There in addition to the Bakwena, they found mobilized against them Bangwaketse, BagaMmanaana, and Bakaa, mephato, altogether numbering some 3000. The Boer Commandant-General, Pieter Scholtz demanded that Sechele turnover the BagaMmanaana Kgosi and agree to submit to Transvaal authority. Sechele replied: "Wait till Monday. I shall not deliver up Mosielele: he is my child. If I am to deliver him up, I shall have to rip open my belly; but I challenge you on Monday to show which is the strongest man. I am, like yourself, provided with arms and ammunition, and have more fighting people than you. I should not have allowed you thus to come in, and would have assuredly fired on you; but I have looked into the book [the Bible], upon which I reserved my fire. I am myself provided with cannon. Keep yourself quiet tomorrow, and do not quarrel for water till Monday; then we shall see who is the strongest man. You are already in my pot; I shall only have to put the lid on it on Monday." A two-day truce was thus arranged during which a number of Boers joined Batswana for Sunday prayers, led by a preacher named Mebalwe. Meanwhile, the two leaders exchanged messages. Sechele asked Scholtz for some tea and sugar, in return offering the General gunpowder if he "had not brought enough with him for a long fight." Scholtz replied he would "soon give Sechele chillies instead." The Bakwena also volunteered to show the Boers where to avoid mogau, as their oxen would surely soon belong to Sechele. Face-to-face negotiations on Monday morning ended in deadlock. Under cover of their artillery the Boers then advanced on the Batswana entrenchments from behind impressed Bahurutshe auxiliaries, using them as human shields. Sechele instructed his men not to fire on their hapless brothers, thus gaining their subsequent allegiance. Various accounts of the battle, including those of Scholtz and Kruger, are consistent in observing that although the initial assault succeeded in scattering many of the defenders, while setting fire to the village, the battle turned into a day long stalemate. Scholtz correspondence further speaks of a six-hour assault on Sechele's battery atop Boswelakgosi hill, concluding: “by nightfall; and with the enemy still holding a rocky hill of caves I was obliged to withdraw my men and return to laager.” While Sechele's cannon provided a focal point for the Boer assault, various sources further underscore the impact of the invaders cannonade and light artillery (swivels). From a September 1852 account by Livingstone: “On Monday they began their attack on the town by firing with swivels. They communicated fire to the houses. This made many of the women flee and the heat became so great the men huddled together on the little hill in the middle of the town - the smoke prevented them from seeing the Boers though the latter saw them huddled in groups. They killed 60 Bakwains and 35 Boers fell - and a great number of horses. Sechele shot 4 Boers with his two double barrelled guns. When they made a dash at the hill, one bullet passing through two men, and a bullet went through the sleeve of his coat...” The above account dovetails with Kruger's recollection that his life had been in danger when an enemy bullet fired “from a huge rifle” passed through his jacket, tearing it in two. Subsequent folklore on both sides maintains that Kruger miraculously escaped Sechele's shot, while affirming Sechele's own brushes with death. New evidence of Sechele's use of high calibre hunting rifles armed with conical shot, moreover, lends greater plausibility to Sekwena traditions extolling his personal, as well as command, role. Three days after the standoff, following a further failed attempt to dislodge Senthufe's Bangwaketse from Kgwakgwe, as well as an abandoned move on Sechele's fallback position at Dithubabruba, Scholtz's commando retreated back into the Transvaal. Thereafter, Sechele's forces raided farms as far as Rustenburg, leading to their abandonment. As a South African newspaper then reported: “The natives have united in a strong body, followed up the retreating force of Boers, and fallen upon the farmers in the Mirique district, and every one of these has been obliged to fall back with the commando upon the Mooi River. Great destruction, of course marked the progress of the conquering natives. Every homestead has been burned, and standing corn ripe for sickle, together with vineyards and gardens, which were then in full bloom, have been entirely destroyed.” In February 1853 the Boers asked for peace, resulting in an armistice. Subsequent reconciliation culminated in Sechele's January 1860 visit to the Potchefstroom home of Transvaal President Marthinus Pretorius, where the two are said to have toasted the New Year together. The boundary that prevailed at the end of the conflict still forms Botswana's eastern frontier with South Africa.[9][10]

First Matabele War

The First Matabele War was fought between 1893 and 1894 in modern-day Zimbabwe. The British South Africa Company had no more than 750 troops in the British South Africa Company's Police, with an undetermined number of possible colonial volunteers and an additional 700 Tswana (Bechuana) allies commandeered by Khama III. The Salisbury and Fort Victoria columns marched into Bulawayo on 4 November 1893. The Imperial column from Bechuanaland was nowhere to be seen. They had set march on 18 October heading north for Bulawayo and had encounter a minor skirmish with the Matabele near Mphoengs on 2 November.They finally reached Bulawayo on 15 November, a delay which probably saved the Charter Company's then newly occupied territory being annexed to Imperial Bechuanaland.[11]

Battle of Khutiyabasadi

Batawana's (Tswana tribe/Clan) fight against invading Ndebeles of 1884. When the Amandebele arrived at Toteng, they thus found the village abandoned. But, as they settled down to enjoy their bloodless conquest, about seventy mounted Batawana under Kgosi Moremi's personal command appeared, all armed with breech-loading rifles. In classic commando style the cavalry began to harass the much larger enemy force with lethal hit and run volleys. Meanwhile, another group of traditionally armed subjects of the Kgosi also made their presence known. At this point the Amandebele commander, Lotshe, took the bait dividing his army into two groups. One party pursued Moremi's small force, while the other fruitlessly tried to catch up to what they believed was the main body of Batawana. As the invaders generally lacked guns, as well as horses, Moremi continued to harass his pursuers, inflicting significant casualties while remaining unscathed. The primary mission of Moremi's men was not, however, to inflict losses on the enemy so much as to ensnare them into a well designed trap. His force thus gradually retreated northward towards Khutiyabasadi, drawing the Amandebele to where the main body of defenders were already well entrenched. As they approached the swamp area south Khutiyabasadi, Lotshe struggled to reunite his men, perhaps sensing that they were approaching a showdown. But, instead Moremi's Batawana, now joined by Qhunkunyane's Wayeyi drew the Amandebele still deeper into the swamps. In this area of poor visibility, due to the thick tall reeds, the Batawana and Wayeyi were able to employ additional tricks to lure the invaders towards their ultimate doom. At one point a calf and its mother were tied to separate trees to make Lotshe's men think that they were finally catching up to their main prize, the elusive Batawana cattle. As they pressed forward the Amandebele were further unnerved by additional hit and run attacks and sniping by small bands of Batawana marksmen. Certainly they could not have been comfortable in the unfamiliar Okavango environment. It was at Kuthiyabasadi that the defenders’ trap was finally sprung. At the time, the place was an island dominated by high reeds and surrounded to the west by deep water. In the reeds, three well armed Batawana regiments, joined by local Wayeyi, waited patiently. There they had built a small wooden platform, upon which several men could be seen from across the channel, as well tunnels and entrenchments for concealment. The Amandebele where drawn to the spot by the appearance of Batawana cavalry who crossed the channel to the island in their sight. In addition, cattle were placed on a small islet adjacent to Kuthiyabasadi, while a group of soldiers now made themselves visible by standing up on the wooden platform. Also at the location was a papyrus bridge that had been purposely weakened at crucial spots. Surveying the scene, Lotshe ordered his men to charge across the bridge over what he presumably thought was no more than a small stream. As planned, the bridge collapsed when full of Amandebele, who were thus unexpectedly thrown into a deep water channel. Few if any would have known how to swim. Additional waves of Amandebele found themselves pinned down by their charging compatriots along the river bank, which was too deep for them to easily ford. With the enemy thus in disarray, the signal was given for the main body of defenders to emerge from their tunnels and trenches. A barrage of bullets cut through Lotshe's lines from three sides, quickly turning the battle into a one-sided massacre. It is said that after the main firing had ceased, the Wayeyi used their mekoro to further attack the survivors trapped in the river, hitting them on the head with their oars. In this way, many more were drowned. By the time the fighting was over, the blood is reported to have turned the water along the course of the river black. While the total number of casualties at Khutiyabasadi cannot be precisely known, observers in Bulawayo at the time confirm that over 2,500 men had left on Lotshe's expedition and less than 500 returned. While the bulk of the Amandebele losses are believed to have occurred in and around Khutiyabasadi itself, survivors of the battle were also killed while being mercilessly pursued by the Batawana cavalry. Moremi was clearly determined to send a strong message to Lobengula that his regiments were no match. Still others died of exhaustion and hunger while trying to make their way home across the dry plains south of Chobe; the somewhat more hospitable route through Gammangwato having been blocked by Khama. While the battle at Khutiyabasadi was a great victory for the Batawana and defeat for the Amandebele, for the Wayeyi of the region the outcome is said to have been a mixed blessing. While they had shared in the victory over the hated Amandebele, one of its consequences was a tightening of Batawana authority in the area over them, as Moremi settled for a period at nearby Nokaneng.[12]

Bophutatswana

The Bophuthatswana Territorial Authority was created in 1961, and in June 1972 Bophuthatswana was declared a self-governing state. On 6 December 1977 this 'homeland' was granted independence by the South African government. Bophuthatswana's capital city was Mmabatho and 99% of its population was Tswana speaking. In March 1994 Bophuthatswana was placed under the control of two administrators, Tjaart van der Walt and Job Mokgoro. The small, widespread pieces of land were reincorporated into South Africa on 27 April 1994. Bophuthatswana is part of the North West Province under Premier Prof Job Mokgoro. On 9 May 2018, Mahumapelo, who was Premier before Prof Mokgoro, announced that he would take leave of absence and appointed Finance MEC Wendy Nelson as acting premier. President Cyril Ramaphosa appointed an inter-ministerial task team to investigate violent protests in the province's capital Mahikeng and other towns through the province over a long period of time. Supra Mahumapelo officially resigned on 23 May 2018.

Setswana Food and Cuisine

Mabele, Bogobe, Seswaa, Serobe, Madila, etc.

Culture & Attire

German Print

Music

Tswana music is mostly vocal and performed, sometimes without drums depending on the occasion; it also makes heavy use of string instruments. Tswana folk music has instruments such as Setinkane (a Botswana version of miniature piano), Segankure/Segaba (a Botswana version of the Chinese instrument Erhu), Moropa (Meropa -plural) (a Botswana version of the many varieties of drums), phala (a Botswana version of a whistle used mostly during celebrations, which comes in a variety of forms). Botswana cultural musical instruments are not confined only to the strings or drums. the hands are used as musical instruments too, by either clapping them together or against phathisi (goat skin turned inside out wrapped around the calf area; it is only used by men) to create music and rhythm. For the last few decades, the guitar has been celebrated as a versatile music instrument for Tswana music as it offers a variety in string which the Segaba instrument does not have. Other notable modern Tswana music is Tswana Rap known as Motswako.[13]

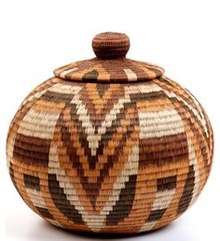

Visual Arts

Batswana are noted for their skill at crafting baskets from Mokola Palm and local dyes. The baskets are generally woven into three types: large, lidded baskets used for storage, large, open baskets for carrying objects on the head or for winnowing threshed grain, and smaller plates for winnowing pounded grain. Potters made clay pots for storing water, traditional beer and also for cooking and hardly for commercial use. Craft makers made wooden crafts and they made traditional cooking utensils such as leso and lehetlho, traditional wooden chairs and drums among others.[14]

Notable Batswana Individuals

- Sir Seretse Khama First President of Botswana

- Ian Khama Fourth President of Botswana

- Sir Ketumile Masire Second President of Botswana

- Festus Mogae Third President of Botswana

- Lucas Mangope Former President of Bophutatswana

- Patrice Motsepe South African Billionaire Mining Businessman

- Mmusi Maimane South African politician

- Tim Modise South African Journalist, TV and Radio Presenter

- Nthato Motlana Dr Nthato was a prominent South African businessman, Physician and Anti-apartheid Activist

- Connie Ferguson Botswana Born South African Actress

- DJ Fresh Botswana Born South African Radio personality

- Shona Ferguson Botswana born Actor and Producer

- Bonang Matheba South African Media Personality

- Mokgweetsi Masisi President of Botswana

- Mpule Kwelagobe Former Miss Universe

- Kaone Kario World Top Model

- Emma Wareus Former Miss World First Princess

- Warona Setshwaelo Hollywood Actress (Quantico)

- Cassper Nyovest aka Refiloe Maele Phoolo, South African Hip Hop Artist

- Sasa Klaas aka Sarona Motlhagodi, is a Botswana female rapper

- HHP South African Artist

- Khuli Chana South African Hip Hop Artist

- Amantle Montsho Former World's 800 Meters Champion

- Cebo Manyaapelo South African Radio and Sports Personaity

- Kaizer Motaung Former South African Footballer. Owner of Kaizer Chiefs FC

- Jimmy Tau Former South African Footballer

- Itumeleng Khune South African Footballer

- Pitso Mosimane South African Football Former Player and Coach and Current Manager of Mamelodi Sundonws

- Percy Tau South African Footballer

- Baboloki Thebe Commonwealth 800 Meters Silver medalist. 4x4 Commonwealth Gold Medalist

- Katlego Maboe South African TV Personality

- Lorna Maskeo South African TV Personality

- Basetsana Khumalo South African TV Personality and Producer. Former Miss South Africa

- Sol PlaatjeSouth African ANC Activist, Writer, Author.

- Keorapetse Kgositsile South African ANC Activist, Writer, Author.

- Mamokgeti Phakeng UCT Vice Chancellor

- Unity Dow Botswana Former High Court Judge, Author, Activist, Minister

- Khama III King of Bechuanaland

- Mogoeng Mogoeng Chief Justice, South Africa

- Tuks Senganga aka Tumelo Kepadisa, Setswana Rapper

- Prof Dan Kgwadi Vice chancellor, North-West University

- Yvonne Mokgoro Former South African Constitution Court Justice

- Redi Tlhabi Journalist, Producer, Author and a Radio Presenter

- Kgosi Leruo Molotlegi King of the Royal Bafokeng Nation

- Supra Mahumapelo South African Politician

- Prof Thapelo Otlogetswe Professor of Corpus Linguistics, Translator and Lexicography at the University of Botswana

- Kagiso Lediga South African Stand-up Comedian, Actor and Director

- Sebele I Former Chief (Kgosi) of the Kwena — a major Tswana tribe (morafe) in modern-day Botswana

- Bathoen I Former Kgosi (paramount chief) of the Ngwaketse

- Z.K. Matthews Was a Prominent black academic in South Africa, lecturing at University of Fort Hare in 1955

- Moses Kotane Was a South African politician and activist

- David Magang is a Botswana lawyer, businessman and politician

Elsewhere

Tswana are notable minorities in a number of neighbouring countries, especially Namibia and Zimbabwe.

See also

References

- 1 2 "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- 1 2 "Census in Brief" (PDF). Statssa.gov.za. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2005. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ https://www.iexplore.com/articles/travel-guides/africa/botswana/history-and-culture

- ↑ http://www.everyculture.com/Bo-Co/Botswana.html

- ↑ "We are Batswana; they call us Batswanan". Linguist Chair. Sunday Standard. Gaborone. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ "Botswana, People and Society, Nationality". The World Factbook. Washington, DC: CIA. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ "Botswana History". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ https://journals.co.za/content/botnotes/23/1/AJA052550590_916

- ↑ http://www.sundaystandard.info/history-bangwaketse-part-19-%E2%80%93-dimawe-and-kgwakgwe

- ↑ http://www.mmegi.bw/index.php?sid=7&aid=1242&dir=2012/June/Friday22

- ↑ http://www.bsap.org/hiscampaigns.html

- ↑ http://www.mmegi.bw/index.php?aid=72905&dir=2017/november/06

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/article/2017-10-27-00-heritage-and-choice-collide-in-setswana-musical?platform=hootsuite

- ↑ http://www.mmegi.bw/index.php?aid=63447&dir=2016/september/28

External links

- "Bechuana". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Bechuanas". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Bechuanas". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Bechuana". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Bechuanas". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- WorldStatesmen website on political and administrative entities, per present state

- Archive.lib.msu.edu

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140202160734/http://mphebathomuseum.org.za/?q=node%2F42

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110304001836/http://www.southafrica.info/about/people/language.htm