Fornax

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | For |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Fornacis |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɔːrnæks/, genitive /fɔːrˈneɪsɪs/ |

| Symbolism | the brazier |

| Right ascension | 3h |

| Declination | −30° |

| Quadrant | SQ1 |

| Area | 398 sq. deg. (41st) |

| Main stars | 2 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 27 |

| Stars with planets | 6 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 2 |

| Brightest star | α For (3.80m) |

| Messier objects | None |

| Meteor showers | None |

| Bordering constellations |

Cetus Sculptor Phoenix Eridanus |

|

Visible at latitudes between +50° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of December. | |

Fornax (/ˈfɔːrnæks/) is a constellation in the southern sky, partly ringed by the celestial river Eridanus. Its name is Latin for furnace. It was named by French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1756. Fornax is one of the 88 modern constellations.

The three brightest stars—Alpha, Beta and Nu Fornacis—form a flattened triangle facing south. With an apparent magnitude of 3.91, Alpha Fornacis is the brightest star in Fornax. Six star systems have been found to have exoplanets.

History

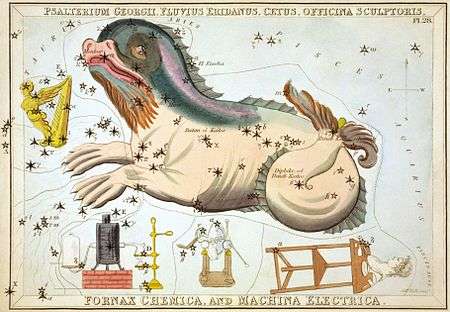

The French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille first described the constellation in French as le Fourneau Chymique (the Chemical Furnace) with an alembic and receiver in his early catalogue,[1] before abbreviating it to le Fourneau on his planisphere in 1752,[2][3] after he had observed and catalogued almost 10,000 southern stars during a two-year stay at the Cape of Good Hope. He devised fourteen new constellations in uncharted regions of the Southern Celestial Hemisphere not visible from Europe. All but one honoured instruments that symbolised the Age of Enlightenment.[lower-alpha 1] Lacaille Latinised the name to Fornax Chimiae on his 1763 chart.[1]

Characteristics

The constellation Eridanus borders Fornax to the east, north and south, while Cetus, Sculptor and Phoenix gird it to the north, west and south respectively. Covering 397.5 square degrees and 0.964% of the night sky, it ranks 41st of the 88 constellations in size,[4] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'For'.[5] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 8 segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 01h 45m 24.18s and 03h 50m 21.34s, while the declination coordinates are between -23.76° and -39.58°.[6] The whole constellation is visible to observers south of latitude 50°N.[lower-alpha 2]

Features

Stars

Lacaille gave Bayer designations to 27 stars now named Alpha to Omega Fornacis, labelling two stars 3.5 degrees apart as Gamma, three stars Eta, two stars Iota, two Lambda and three Chi. Phi Fornacis was added by Gould, and Theta and Omicron were dropped by Gould and Baily respectively. Upsilon, too, was later found to be two stars and designated as such.[1] Overall, there are 59 stars within the constellation's borders brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[lower-alpha 3][4] However, there are no stars brighter than the fourth magnitude.[8]

The three brightest stars form a flattish triangle, with Alpha (also called Dalim[9]) and Nu Fornacis marking its eastern and western points and Beta Fornacis marking the shallow southern apex.[10] Originally designated 12 Eridani by John Flamsteed, Alpha Fornacis was named by Lacaille as the brightest star in the new constellation.[1] It is a binary star that can be resolved by small amateur telescopes. With an apparent magnitude of 3.91, the primary is a yellow-white subgiant 1.21 times as massive as the Sun that has begun to cool and expand after exhausting its core hydrogen, having swollen to 1.9 times the Sun's radius. Of magnitude 6.5, the secondary star is 0.78 times as massive as the Sun. It has been identified as a blue straggler, and has either accumulated material from, or merged with, a third star in the past. It is a strong source of X-rays.[11] The pair is 46.4 ± 0.3 light-years distant from Earth.[12]

Beta Fornacis is a yellow-hued giant star of spectral type G8IIIb of magnitude 4.5 that has cooled and swelled to 11 times the Sun's diameter,[13] 169 ± 6 light-years from Earth.[12] It is a red clump giant, which means it has undergone helium flash and is currently generating energy through the fusion of helium at its core.[14]

Nu Fornacis is 370 ± 10 light-years distant from Earth.[12] It is a blue giant star of spectral type B9.5IIIspSi that is 3.65 ± 0.18 times as massive and around 245 times as luminous as the Sun, with 3.2 ± 0.4 times its diameter.[15] It varies in luminosity over a period of 1.89 days—the same as its rotational period.[16] This is because of differences in abundances of metals in its atmosphere; it belongs to a class of star known as an Alpha2 Canum Venaticorum variable.

Shining with an apparent magnitude of 5.89, Epsilon Fornacis is a binary star system located 105 ± 1 light-years distant from Earth.[12] Its component stars orbit each other every 37 years. The primary star is around 12 billion years old and has cooled and expanded to 2.53 times the diameter of the Sun, while having only 91% of its mass. [17] Omega Fornacis is a binary star system composed of a blue main-sequence star of spectral type B9.5V and magnitude 4.96, and a white main sequence star of spectral type A7V and magnitude 7.88.

LP 944-20 is a brown dwarf of spectral type M9 that has around 7% the mass of the Sun. Approximately 21 light-years distant from Earth, it is a faint object with an apparent magnitude of 18.69.[18] Observations published in 2007 showed that the atmosphere of LP 944-20 contains much lithium and that it has dusty clouds.[19] Smaller and less luminous still is 2MASS 0243-2453, a T-type brown dwarf of spectral type T6. With a surface temperature of 1040–1100 K, it has 2.4–4.1% the mass of the Sun, a diameter 9.2 to 10.6% of that of the Sun, and an age of 0.4–1.7 billion years.[20]

Six star systems in Fornax have been found to have planets:

- Lambda2 Fornacis is a star about 1.2 times as massive as the Sun with a planet about as massive as Neptune, discovered by doppler spectroscopy in 2009. The planet has an orbit of around 17.24 days.[21]

- HD 20868 is an orange dwarf with a mass around 78% that of the Sun, 151 ± 10 light-years away from Earth. It was found to have an orbiting planet approximately double the mass of Jupiter with a period of 380 days.[22]

- WASP-72 is a star around 1.4 times as massive that has begun to cool and expand off the main sequence, reaching double the Sun's diameter. It has a planet around as massive as Jupiter orbiting it every 2.2 days.[23]

- HD 20781 and HD 20782 are a pair of sunlike yellow main sequence stars that orbit each other. Each has been found to have planets.

Deep-sky objects

NGC 1049 is a globular cluster 500,000 light-years from Earth. It is in the Fornax Dwarf Galaxy.[25] NGC 1360 is a planetary nebula in Fornax with a magnitude of approximately 9.0, 978 light-years from Earth. Its central star is of magnitude 11.4, an unusually bright specimen. It is five times the size of the famed Ring Nebula in Lyra at 6.5 arcminutes. Unlike the Ring Nebula, NGC 1360 is clearly elliptical.[26]

The Fornax Dwarf galaxy is a dwarf galaxy that is part of the Local Group of galaxies. It is not visible in amateur telescopes, despite its relatively small distance of 500,000 light-years.[27]

NGC 1097 is a barred spiral galaxy in Fornax, about 60 million light-years from Earth. At magnitude 9, it is visible in medium amateur telescopes.[29] It is notable as a Seyfert galaxy with strong spectral emissions indicating ionized gases and a central supermassive black hole.

NGC 1365 is another barred spiral galaxy located at a distance of 60 million light-years from Earth. Like NGC 1097, it is also a Seyfert galaxy. Its bar is a center of star formation and shows extensions of the spiral arms' dust lanes. The bright nucleus indicates the presence of an active galactic nucleus - a galaxy with a supermassive black hole at the center, accreting matter from the bar.[30] It is a 10th magnitude galaxy associated with the Fornax Cluster.[29]

Fornax A is a radio galaxy with extensive radio lobes that corresponds to the optical galaxy NGC 1316, a 9th-magnitude galaxy.[27] One of the closer active galaxies to Earth at a distance of 80 million light-years, Fornax A appears in the optical spectrum as a large elliptical galaxy with dust lanes near its core. These dust lanes have caused astronomers to discern that it recently merged with a small spiral galaxy. Because it has a high rate of type Ia supernovae, NGC 1316 has been used to determine the size of the universe. The jets producing the radio lobes are not particularly powerful, giving the lobes a more diffuse, knotted structure due to interactions with the intergalactic medium.[30] Associated with this peculiar galaxy is an entire cluster of galaxies.[27]

Fornax has been the target of investigations into the furthest reaches of the universe. The Hubble Ultra Deep Field is located within Fornax, and the Fornax Cluster, a small cluster of galaxies, lies primarily within Fornax. At a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society in Britain, a team from University of Queensland described 40 unknown "dwarf" galaxies in this constellation; follow-up observations with the Hubble Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope revealed that ultra compact dwarfs are much smaller than previously known dwarf galaxies, about 120 light-years (37 pc) across.[31]

UDFj-39546284 is a candidate protogalaxy located in Fornax,[32][33][34][35] although recent analyses have suggested it is likely to be a lower redshift source.[36][37]

Equivalents

In Chinese astronomy, the stars that correspond to Fornax are within the White Tiger of the West (西方白虎, Xī Fāng Bái Hǔ).[38]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The exception is Mensa, named for the Table Mountain. The other thirteen (alongside Fornax) are Antlia, Caelum, Circinus, Horologium, Microscopium, Norma, Octans, Pictor, Pyxis, Reticulum, Sculptor and Telescopium.[1]

- ↑ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between 50°N and 66°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon for to all intents and purposes unobservable.[4]

- ↑ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 6–7, 152. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille's Southern Planisphere of 1756". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Lacaille, Nicolas Louis (1756). "Relation abrégée du Voyage fait par ordre du Roi au cap de Bonne-espérance". Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French): 519–592 [588].

- 1 2 3 Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ "Fornax, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Fornax". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, Mark (2013). A Down to Earth Guide to the Cosmos. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-2691-0.

- ↑ Fuhrmann, K.; Chini, R. (2015). "Multiplicity among F-type Stars. II". The Astrophysical Journal. 809 (1): 19. Bibcode:2015ApJ...809..107F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/809/1/107. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

- ↑ Pasinetti Fracassini, L. E.; Pastori, L.; Covino, S.; Pozzi, A. (2001). "Catalogue of Apparent Diameters and Absolute Radii of Stars (CADARS) - Third edition - Comments and statistics". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 367: 521–24. arXiv:astro-ph/0012289. Bibcode:2001A&A...367..521P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000451.

- ↑ Kubiak, M.; McWilliam, A.; Udalski, A.; Gorski, K. (2002). "Metal Abundance of Red Clump Stars in Baade's Window". Acta Astronomica. 52: 159–75. Bibcode:2002AcA....52..159K.

- ↑ North, P. (1998). "Do SI stars undergo any rotational braking?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 334: 181–87. arXiv:astro-ph/9802286. Bibcode:1998A&A...334..181N.

- ↑ Leone, F.; Catanzaro, G.; Malaroda, S. (2000). "A spectroscopic study of the magnetic chemically peculiar star nu Fornacis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 359: 635–38. Bibcode:2000A&A...359..635L.

- ↑ Jofré, E.; et al. (2015). "Stellar parameters and chemical abundances of 223 evolved stars with and without planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 574: A50. arXiv:1410.6422. Bibcode:2015A&A...574A..50J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424474.

- ↑ Research Consortium on Nearby Stars (1 January 2012). "The 100 nearest star systems". RECONS. Georgia State University. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ Pavlenko, Ya. V.; Jones, H. R. A.; Martín, E. L.; Guenther, E.; Kenworthy, M. A.; Zapatero Osorio, M. R. (September 2007). "Lithium in LP944-20". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 380 (3): 1285–96. arXiv:0707.0694. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.380.1285P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12182.x.

- ↑ Burgasser AJ, Burrows A, Kirkpatrick JD (2006). "Method for Determining the Physical Properties of the Coldest Known Brown Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal. 639 (2): 1095–1113. arXiv:astro-ph/0510707. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639.1095B. doi:10.1086/499344.

- ↑ O’Toole, Simon; Tinney, C. G.; Butler, R. Paul; Jones, Hugh R. A.; Bailey, Jeremy; Carter, Brad D.; Vogt, Steven S.; Laughlin, Gregory; Rivera, Eugenio J. (2009). "A Neptune-mass Planet Orbiting the Nearby G Dwarf HD16417". The Astrophysical Journal. 697 (2): 1263–1268. arXiv:0902.4024. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697.1263O. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/2/1263.

- ↑ Moutou, C.; Mayor, M.; Lo Curto, G.; Udry, S.; Bouchy, F.; Benz, W.; Lovis, C.; Naef, D.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D.; Santos, N. C. (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XVII. Six long-period giant planets around BD -17 0063, HD 20868, HD 73267, HD 131664, HD 145377, HD 153950". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 496 (2): 513–19. arXiv:0810.4662. Bibcode:2009A&A...496..513M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810941.

- ↑ Gillon M, Anderson DR, Collier-Cameron A, Doyle AP, Fumel A, Hellier C, Jehin E, Lendl M, Maxted PF, Montalbán J, Pepe F, Pollacco D, Queloz D, Ségransan D, Smith AM, Smalley B, Southworth J, Triaud AH, Udry S, West RG (2013). "WASP-64 b and WASP-72 b: two new transiting highly irradiated giant planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 552: 13. arXiv:1210.4257. Bibcode:2013A&A...552A..82G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220561. A82.

- ↑ "Four globular clusters in Fornax". www.spacetelescope.org. ESA/Hubble. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Levy 2005, p. 176.

- ↑ Levy 2005, pp. 134-135.

- 1 2 3 Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 148-149.

- ↑ "MUSE Probes Uncharted Depths of Hubble Ultra Deep Field - Deepest ever spectroscopic survey completed". www.eso.org. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- 1 2 Ridpath & Tirion, pp. 148-149.

- 1 2 Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ↑ Hilker, Michael; Baumgardt, Holger; Infante, Leopoldo; Drinkwater, Michael; Evstigneeva, Ekaterina; Gregg, Michael (September 2007). "Weighing Ultracompact Dwarf Galaxies in the Fornax Cluster" (PDF). The Messenger (129).

- ↑ Wall, Mike (December 12, 2012). "Ancient Galaxy May Be Most Distant Ever Seen". Space.com. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

13.75 Big Bang - 0.38 = 13.37

- ↑ NASA, "NASA's Hubble Finds Most Distant Galaxy Candidate Ever Seen in Universe", 26 January 2011

- ↑ "Hubble finds a new contender for galaxy distance record". Space Telescope (heic1103 - Science Release). 26 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ HubbleSite, "NASA's Hubble Finds Most Distant Galaxy Candidate Ever Seen in Universe", STScI-2011-05, 26 January 2011

- ↑ Brammer, Gabriel B. (2013). "A Tentative Detection of an Emission Line at 1.6 mum for the z ~ 12 Candidate UDFj-39546284". The Astrophysical Journal. 765: L2. arXiv:1301.0317. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L...2B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/l2.

- ↑ Bouwens, R. J.; Oesch, P. A.; Illingworth, G. D.; Labbé, I.; van Dokkum, P. G.; Brammer, G.; Magee, D.; Spitler, L. R.; Franx, M.; Smit, R.; Trenti, M.; Gonzalez, V.; Carollo, C. M. (2013). "Photometric Constraints on the Redshift of z ~ 10 Candidate UDFj-39546284 from Deeper WFC3/IR+ACS+IRAC Observations over the HUDF". The Astrophysical Journal. 765: L16. arXiv:1211.3105. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L..16B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/l16.

- ↑ (in Chinese) AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 7 月 10 日

Cited texts

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fornax. |