Sextans

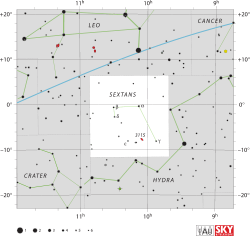

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Sex |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Sextantis, Sextansis |

| Pronunciation |

/ˈsɛkstənz/, genitive /sɛksˈtæntɪs/ |

| Symbolism | the Sextant |

| Right ascension | 10h |

| Declination | 0° |

| Quadrant | SQ2 |

| Area | 314 sq. deg. (47th) |

| Main stars | 3 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 28 |

| Stars with planets | 5 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 5 |

| Brightest star | α Sex (4.49m) |

| Messier objects | None |

| Meteor showers | Sextantids |

| Bordering constellations |

Leo Hydra Crater |

|

Visible at latitudes between +80° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of April. | |

Sextans is a minor equatorial constellation which was introduced in 1687 by Johannes Hevelius. Its name is Latin for the astronomical sextant, an instrument that Hevelius made frequent use of in his observations.

Notable features

Sextans as a constellation covers a rather dim, sparse region of the sky. It has only one star above the fifth magnitude, namely α Sextantis at 4.49m. The constellation contains a few double stars, including γ, 35, and 40 Sextantis. There are a few notable variable stars, including β, 25, 23 Sextantis, and LHS 292. NGC 3115, an edge-on lenticular galaxy, is the only noteworthy deep-sky object. It also lies near the ecliptic, which causes the Moon, and some of the planets to occasionally pass through it for brief periods of time.

The constellation is the location of the field studied by the COSMOS project, undertaken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Sextans B is a fairly bright dwarf irregular galaxy at magnitude 6.6, 4.3 million light-years from Earth. It is part of the Local Group of galaxies.[1]

CL J1001+0220 is as of 2016 the most distant known galaxy cluster at redshift z=2.506, 11.1 billion light-years from Earth.[2]

In June 2015, astronomers reported evidence for Population III stars in the Cosmos Redshift 7 galaxy (at z = 6.60) found in Sextans. Such stars are likely to have existed in the very early universe (i.e., at high redshift), and may have started the production of chemical elements heavier than hydrogen that are needed for the later formation of planets and life as we know it.[3][4]

Gallery

References

- ↑ Levy 2005, p. 178.

- ↑ Wang, Tao; Elbaz, David; Daddi, Emanuele; Finoguenov, Alexis; Liu, Daizhong; Schrieber, Corenin; Martin, Sergio; Strazzullo, Veronica; Valentino, Francesco; van Der Burg, Remco; Zanella, Anita; Cisela, Laure; Gobat, Raphael; Le Brun, Amandine; Pannella, Maurilio; Sargent, Mark; Shu, Xinwen; Tan, Qinghua; Cappelluti, Nico; Li, Xanxia (2016). "Discovery of a galaxy cluster with a violently starbursting core at z=2.506". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (1). arXiv:1604.07404. Bibcode:2016ApJ...828...56W. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/828/1/56.

- ↑ Sobral, David; Matthee, Jorryt; Darvish, Behnam; Schaerer, Daniel; Mobasher, Bahram; Röttgering, Huub J. A.; Santos, Sérgio; Hemmati, Shoubaneh (4 June 2015). "Evidence For POPIII-Like Stellar Populations In The Most Luminous LYMAN-α Emitters At The Epoch Of Re-Ionisation: Spectroscopic Confirmation". The Astrophysical Journal. 808: 139. arXiv:1504.01734. Bibcode:2015ApJ...808..139S. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/808/2/139.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (17 June 2015). "Astronomers Report Finding Earliest Stars That Enriched Cosmos". New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "A gigantic cosmic bubble". www.eso.org. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sextans. |