Oceanus

| Oceanus | |

|---|---|

| Titan god of the sea | |

| Member of the Titans | |

|

Oceanus in the Trevi Fountain, Rome | |

| Other names | Ogen or Ogenus |

| Abode | River Oceanus, Arcadia |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Tethys |

| Offspring | Thetis, Metis, Amphitrite, Dione, Pleione, Nede, Nephele, Amphiro, and the other Oceanids, Inachus, Amnisos and the other Potamoi |

| Parents | Uranus and Gaia |

| Siblings |

|

| Roman equivalent | Oceanus |

Oceanus (/oʊˈsiːənəs/; Greek: Ὠκεανός Ōkeanós,[1] pronounced [ɔːkeanós]), also known as Ogenus (Ὤγενος Ōgenos or Ὠγηνός Ōgēnos) or Ogen (Ὠγήν Ōgēn),[2] was a divine figure in classical antiquity, believed by the ancient Greeks and Romans to be the divine personification of the sea, an enormous river encircling the world.

Etymology

R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek proto-form *-kay-an-.[3] In contrast, Michael Janda has reminded the scientific community of an earlier comparison[4] of the Vedic dragon Vṛtra's attribute āśáyāna- "lying on [the waters]" and Greek Ὠκεανός (Ōkeanós), which he sees as phonetical equivalents of each other, both stemming from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root *ō-kei-ṃ[h1]no- "lying on", related to Greek κεῖσθαι (keîsthai "to lie").[5] Janda furthermore points to early depictions of Okeanos with a snake's body,[6] which seem to confirm the mythological parallel with the Vedic dragon Vṛtra.

Another parallel naming can be found in Greek ποταμός (potamós "broad body of water") and Old English fæðm "embrace, envelopment, fathom" which is notably attested in the Old English poem Helena (v. 765) as dracan fæðme "embrace of the dragon" and is furthermore related (via Germanic *faþma "spreading, embrace") to Old Norse Faðmir or Fáfnir the well-known name of a dragon in the 13th century Völsunga saga; all three words derive from PIE *poth2mos "spreading, expansion" and thus bind together the Greek word for a "broad river, stream" with the Germanic expressions connected to the dragon's "embrace".[5]

Mythological account

.jpg)

According to Homer, Oceanus was the ocean-stream at the margin of the habitable world (οἰκουμένη, oikouménē), the father of everything,[7][8] limiting it from the underworld[9] and flowing around the Elysium.[10] Hence Odysseus has to traverse it in order to arrive in the realm of the dead.[11] In the Iliad, Hera mentions her intended journey to her foster parents, namely "Oceanus, from whom they all are sprung":

εἶμι γὰρ ὀψομένη πολυφόρβου πείρατα γαίης, : Ὠκεανόν τε θεῶν γένεσιν καὶ μητέρα Τηθύν, : οἵ μ' ἐν σφοῖσι δόμοισιν ἐὺ τρέφον ἠδ' ἀτίταλλον : δεξάμενοι Ῥείας […]

- (For I am faring to visit the limits of the all-nurturing earth,

- and Oceanus, from whom the gods are sprung, and mother Tethys,

- even them that lovingly nursed and cherished me in their halls,

- when they had taken me from Rhea […])[7]

Helios rises from the deep-flowing Oceanus in the east[12] and at the end of the day sinks back into the Oceanus in the west.[13] Also the other stars "bathe […] in the stream of Ocean".[14] Oceanus is called βαθύρροος (“deep-flowing”)[15] and ἀψόρροος (“flowing back to itself, circular”),[16] the latter quality being reflected in its depiction on the shield of Achilles:

- Ἐν δ' ἐτίθει ποταμοῖο μέγα σθένος Ὠκεανοῖο

- ἄντυγα πὰρ πυμάτην σάκεος πύκα ποιητοῖο.

- (Therein he set also the great might of the river Oceanus,

- around the uttermost rim of the strongly-wrought shield.)[17]

In Greek mythology, this ocean-stream was personified as a Titan, the eldest son of Uranus and Gaia. Oceanus' consort is his sister Tethys, and from their union came the ocean nymphs, also referred to as the three-thousand Oceanids, and all the rivers of the world, fountains, and lakes.[18]

In most variations of the war between the Titans and the Olympians, or Titanomachy, Oceanus, along with Prometheus and Themis, did not take the side of his fellow Titans against the Olympians, but instead withdrew from the conflict. In most variations of this myth, Oceanus also refused to side with Cronus in the latter's revolt against their father, Uranus. He is, it appears, some sort of an outlaw to the society of Gods, as he also does not – and unlike all the other river gods, his sons – take part in the convention of gods on Mount Olympus.[19]

Besides, Oceanus appears as a representative of the archaic world that Heracles constantly threatened and bested. As such, the Suda identifies Oceanus and Tethys as the parents of the two Kerkopes, whom Heracles also bested. Heracles forced Helios to lend him his golden bowl, in order to cross the wide expanse of the Ocean on his trip to the Hesperides. When Oceanus tossed the bowl about, Heracles threatened him and stilled his waves. The journey of Heracles in the sun-bowl upon Oceanus became a favored theme among painters of Attic pottery.

Iconography

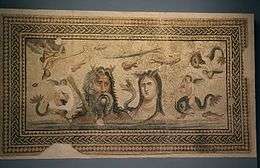

In Hellenistic and Roman mosaics, this Titan was often depicted as having the upper body of a muscular man with a long beard and horns (often represented as the claws of a crab) and the lower body of a serpent (cfr. Typhon). On a fragmentary archaic vessel of circa 580 BC (British Museum 1971.11-1.1), among the gods arriving at the wedding of Peleus and the sea-nymph Thetis, is a fish-tailed Oceanus, with a fish in one hand and a serpent in the other, gifts of bounty and prophecy.[6] In Roman mosaics, such as that from Bardo, he might carry a steering-oar and cradle a ship.

In cosmography and geography

.jpg)

Oceanus appears in Hellenic cosmography as well as myth. Both Homer[20] and Hesiod[21] refer to Okeanós Potamós, the "Ocean Stream". When Odysseus and Nestor walk together along the shore of the sounding sea they address their prayers "to the great Sea-god who girdles the world".[22] Cartographers continued to represent the encircling equatorial stream much as it had appeared on Achilles' shield.[8]

Herodotus was skeptical about the physical existence of Oceanus and rejected the reasoning—proposed by some of his coevals—according to which the uncommon phenomenon of the summerly Nile flood was caused by the river's connection to the mighty Oceanus. Speaking about the Oceanus myth itself he declared:

As for the writer who attributes the phenomenon to the ocean, his account is involved in such obscurity that it is impossible to disprove it by argument. For my part I know of no river called Ocean, and I think that Homer, or one of the earlier poets, invented the name, and introduced it into his poetry.[23]

Some scholars believe that Oceanus originally represented all bodies of salt water, including the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, the two largest bodies known to the ancient Greeks. However, as geography became more accurate, Oceanus came to represent the stranger, more unknown waters of the Atlantic Ocean (also called the "Ocean Sea"), while the newcomer of a later generation, Poseidon, ruled over the Mediterranean Sea.

Late attestations for an equation with the Black Sea abound, the cause being – as it appears – Odysseus' travel to the Cimmerians whose fatherland, lying beyond the Oceanus, is described as a country divested from sunlight.[9] In the fourth century BC, Hecataeus of Abdera writes that the Oceanus of the Hyperboreans is neither the Arctic nor Western Ocean, but the sea located to the north of the ancient Greek world, namely the Black Sea, called "the most admirable of all seas" by Herodotus,[24] labelled the "immense sea" by Pomponius Mela[25] and by Dionysius Periegetes,[26] and which is named Mare majus on medieval geographic maps. Apollonius of Rhodes, similarly, calls the lower Danube the Kéras Okeanoío ("Gulf" or "Horn of Oceanus").[27]

Hecataeus of Abdera also refers to a holy island, sacred to the Pelasgian (and later, Greek) Apollo, situated in the easternmost part of the Okeanós Potamós, and called in different times Leuke or Leukos, Alba, Fidonisi or Isle of Snakes. It was on Leuke, in one version of his legend, that the hero Achilles, in a hilly tumulus, was buried (which is erroneously connected to the modern town of Kiliya, at the Danube delta). Accion ("ocean"), in the fourth century AD Gaulish Latin of Avienus' Ora maritima, was applied to great lakes.[28]

Genealogical chart

| Oceanus's family tree [29] |

|---|

See also

References

- ↑ Ὠκεανός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Ὤγενος in Liddell and Scott.

- ↑ Robert S. P. Beekes: Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Brill, 2009, p. xxxv.

- ↑ Traced back to Adalbert Kuhn, ὠκεανός, in: Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiet des Deutschen, Griechischen und Lateinischen, vol. 9 (1860), 240, who had refined an earlier suggestion by Theodor Benfey. At around the same time, the Swiss linguist Adolphe Pictet had published quite the same discovery in his Les origines indo-européennes, ou les Aryas primitifs. Essai de paléontologie linguistique. Paris 1859, Band 1, S. 116.

- 1 2 Michael Janda: Die Musik nach dem Chaos. Der Schöpfungsmythos der europäischen Vorzeit. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2010, p. 57 ff.

- 1 2 London 1971.11-1.1 (Vase) at the Perseus Digital Library. See the whole object in several photos on the site of the British Museum. Cfr. also the entry on Theoi Greek Mythology.

- 1 2 Iliad XIV, 200 ff., 245 f. and 301 ff.

- 1 2 Livio Catullo Stecchini. "Ancient Cosmology". www.metrum.org. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- 1 2 Odyssey XI, 13–19.

- ↑ Odyssey IV, 563–569.

- ↑ Odyssey XI, 639 f.

- ↑ Iliad VII, 421 f.; VIII, 485; XVIII, 239 ff.; Odyssey XIX, 433 f.

- ↑ Iliad VIII, 485.

- ↑ Iliad V, 5; XVIII, 489.

- ↑ Iliad VII, 422; XIV, 311.

- ↑ Iliad XVIII, 399; Odyssey XX, 65.

- ↑ Iliad XVIII, 607 f.

- ↑ The late classical poet Nonnus mentioned "the Limnai [Lakes], liquid daughters of Oceanus" (Dionysiaca VI, 352).

- ↑ Iliad XX, 4–8.

- ↑ Odyssey XII, 1.

- ↑ Theogonia V, 242, 959.

- ↑ Iliad IX, 182.

- ↑ Histories II, 21 ff.

- ↑ Histories IV, 85.

- ↑ De situ orbis I, 19.

- ↑ Orbis Descriptio V, 165.

- ↑ Argonautica IV, 282.

- ↑ Mullerus in Cl. Ptolemaei Geographia, ed. Didot, p. 235.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- ↑ Although usually the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, as in Hesiod, Theogony 371–374, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- ↑ According to Hesiod, Theogony 507–511, Clymene, one of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351, was the mother by Iapetus of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus, while according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus.

- ↑ According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- ↑ In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

Sources

- Aeschylus, Persians. Seven against Thebes. Suppliants. Prometheus Bound. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Loeb Classical Library No. 145. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99627-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (June 1, 1987). ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hymn to Hermes (4), in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Karl Kerenyi. The Gods of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson, 1951.

External links

- Livio Catullo Stecchini, "Ancient Cosmology"