Jebel Sahaba

| Jebel Sahaba | |

|---|---|

Jebel Sahaba (جبلْ الصحابة) | |

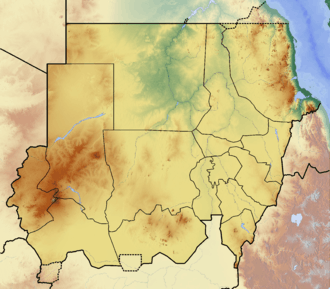

| Location | Sudan |

| Coordinates | 21°59′N 31°20′E / 21.983°N 31.333°ECoordinates: 21°59′N 31°20′E / 21.983°N 31.333°E |

Jebel Sahaba (also Site 117) is a prehistoric cemetery site in the Nile Valley (now submerged in Lake Nasser), near the northern border of Sudan, associated with the Qadan culture, dated to the Younger Dryas (some 12,000 to 14,000 years old).[1][2] It was discovered in 1964 by a team led by Fred Wendorf.

The site is often cited as the oldest known evidence of warfare or systemic intergroup violence.[3]

Discovery

The original project that discovered the cemetery was the UNESCO High Dam Salvage Project.[4] This salvage dig project was a direct response to the raising of the Aswan Dam which stood to destroy or damage many sites along its path.

Three cemeteries are present in this area. Of these cemeteries, two comprise Jebel Sahaba, with one cemetery located on either side of the Nile. A third cemetery, Tuskha, is situated nearby.

Skeletal remains

61 individual skeletons were recovered at Jebel Sahaba, as well as numerous other fragmented remains. Of the men, women, and children buried at Jebel Sahaba, at least 45% percent died of violent wounds.[5] Pointed stone projectiles were found in the bodies of 21 individuals, suggesting that these people had been attacked by spears or arrows. Cut marks were found on the bones of other individuals as well.[5] Some damaged bones had healed, demonstrating a persistent pattern of conflict in this society.[5]

Cranial analysis of the Jebel Sahaba fossils found that they shared osteological affinities with a hominid series from Wadi Halfa in Sudan.[6] Additionally, comparison of the limb proportions of the Jebel Sahaba skeletal remains with those of various ancient and recent series indicated that they were most similar in body shape to the examined modern populations from Sub-Saharan Africa (viz. 19th century fossils belonging to the San population, 19th century West Africa fossils, 19th and 20th century Pygmy fossils, and mid-20th century fossils culled from Kenya and Uganda in East Africa). However, the Jebel Sahaba specimens were post-cranially distinct from the Iberomaurusians and other coeval series from North Africa, and they were also morphologically remote from later Nubia skeletal series and from fossils belonging to the Mesolithic Natufian culture of the Levant.[7]

Curation

The skeletal remains and any other artifacts recovered by the UNESCO High Dam Salvage Project were donated by Wendorf to the British Museum in 2001; the collection arrived at the museum in March 2002.[8] This collection includes skeletal and fauna remains, lithics, pottery, and environmental samples as well as the full archive of Wendorf's notes, slides, and other material during the dig.

See also

References

- ↑ One skeleton was radiocarbon dated to approximately 13,140-14,340 years old; Dawn of Ancient Warfare. Ancient Military History. Retrieved December 17, 2011 Newer apatite dates indicate that the site is at least 11,600 years old. Antoine, Daniel; Zazzo, Antoine; Friedman, Renée (2013). "Revisiting Jebel Sahaba: new apatite radiocarbon dates for one of the Nile valley's earliest cemeteries". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 150: 68. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22247.

- ↑ Antoine, D.; Zazzo, A.; Freidman, R. (2013). "Revisiting Jebel Sahaba: New Apatite Radiocarbon Dates for One of the Nile Valley's Earliest Cemeteries". American Journal of Physical Anthropology Supplement. 56: 68.

- ↑ Kelly, Raymond (October 2005). "The evolution of lethal intergroup violence". PNAS. 102: 24–29. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102. PMC 1266108. PMID 16129826. . Some anthropologists argue that the deaths were linked to environmental pressures. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/2060/pdf

- ↑ http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-173-2.pdf

- 1 2 3 Friedman, Renée. "Violence and climate change in prehistoric Egypt and Sudan". British Museum blog.

- ↑ Bräuer, G. (1978). "The morphological differentiation of anatomically modern man in Africa, with special regard to recent finds from East Africa". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie: 266–292. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ↑ Holliday, T. W. (2015). "Population affinities of the Jebel Sahaba skeletal sample: Limb proportion evidence". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 25 (4): 466–476. doi:10.1002/oa.2315. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ↑ Margaret Judd, "Jebel Sahaba Revisited", Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa, Studies in African Archaeology 9 (2006), 153–166.

Further reading

- F. Wendorf, 'Site 117: A Nubian Final Paleolithic Graveyard near Jebel Sahaba, Sudan'. In: F. Wendorf, Editor, The Prehistory of Nubia, Southern Methodist University, Dallas (1968), pp. 954–987.