Siege of Diu

Coordinates: 20°N 71°E / 20°N 71°E

| First Siege of Diu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Ottoman-Portuguese War | |||||||

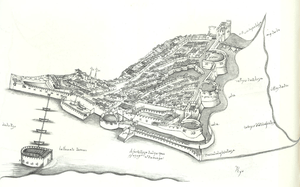

Contemporary drawing of the fortress of Diu in the 16th century. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| António da Silveira |

Khadjar Safar Hadım Suleiman Pasha | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

600 men (garrison)[1] 139 ships 186 cannon |

16,000 Gujarati [2] 6,000 Ottomans[3] 79 ships[3] 130 cannon[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| All killed or wounded but 40[5] | 3,000 casualties[5] | ||||||

Siege of Diu (1538) Location within India | |||||||

The Siege of Diu occurred when an army of the Sultanate of Gujarat under Khadjar Safar, aided by forces of the Ottoman Empire attempted to capture the city of Diu in 1538, then held by the Portuguese. The Portuguese successfully resisted the four months long siege. It is part of The Ottoman-Portuguese War.

Background

In 1509, the major Battle of Diu (1509) took place between the Portuguese and a joint fleet of the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, the Zamorin of Calicut with support of the Ottoman Empire. Since 1517, the Ottomans had attempted to combine forces with Gujarat in order to fight the Portuguese away from the Red Sea and in the area of India.[4] Pro-Ottoman forces under Captain Hoca Sefer had been installed by Selman Reis in Diu.[4]

Diu in Gujarat (now a state in western India), was with Surat, one of the main points of supply of spices to Ottoman Egypt at that time. However, Portuguese intervention thwarted that trade by controlling the traffic in the Red Sea.[4] In 1530, the Venetians could not obtain any supply of spices through Egypt.[4]

Under the command of governor Nuno da Cunha, the Portuguese had attempted to capture Diu by force in February 1531, unsuccessfully.[4] Thereafter, the Portuguese waged war on Gujarat, devastating its shores and several cities like Surat.[6]

Soon after however, the Sultan of Gujarat, Bahadur Shah, who was under threat from the Mughal emperor Humayun made an agreement with the Portuguese, granting them Diu in exchange for Portuguese assistance against the Mughals and protection should the realm fall.[4] The Portuguese seized the stronghold of Gogala (Bender-i Türk) near the city,[4] and built the Diu Fort. Once the threat from Humayun was removed, Bahadur tried to negotiate the withdrawal of the Portuguese, but on 13 February 1537 he died drowning during the negotiations on board of a Portuguese ship in unclear circumstances, both sides blaming the other for the tragedy.[7]

Bahadur Shah had also appealed to the Ottomans to expel the Portuguese, which led to the 1538 expedition.[4]

The Ottoman Fleet

Upon the arrival of Sultan Bahadur's envoy to Egypt with a large tribute in 1536, the Ottoman governor (pasha) of Egypt, 60 year old eunuch Hadim Suleiman Pasha, was nominated by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to organize and personally lead an expedition to India.[4] Pasha Suleiman forbade any shipping out of the Red Sea to avoid leaking information to the Portuguese in India.[8] There were delays however due to the Siege of Coron in the Mediterranean, and the Ottoman-Safavid war of 1533–1535.[4]

According to the Tarikh al-Shihri, Ottoman forces amounted to 80 vessels and 40,000 men.[9] Gaspar Correia provides a more specific account, claiming that the Turks assembled at Suez an armada composed of 15 "bastard galleys" (it), 40 "royal galleys", 6 galliots, 5 galleons "with four masts each" that were "dangerous ships to sail, for they were shallow with no keel"; five smaller craft, six foists from Gujarat, and two brigs. It carried over 400 artillery pieces in total, over 10,000 sailors and rowers (of which 1500 were Christian) and 6,000 soldiers, of which 1500 were janissaries. The Pasha employed a Venetian renegade, Francisco, as captain of 10 galleys, plus 800 Christian mercenaries.[10] On July 20, 1538, the armada set sail from Jeddah, stopping by Kamaran Island before proceeding to Aden.

At Aden, Pasha Suleiman captured the city after inviting it's ruler, Sheikh Amir bin Dawaud, favourable towards the Portuguese, aboard his ships, then hanging him. Thus, Aden was occupied without a siege, and plundered.[4][11]

The expedition left Aden in August 19 and then called at Socotra, thereafter making its way to the western coast of Gujarat, despite losing some ships that got separated from the fleet during the passage of the Indian Ocean.[4][12] It was the largest Ottoman fleet ever sent into the Indian Ocean.[13]

The Siege

The captain of Diu at the time was the experienced António da Silveira, former captain of Bassein and Hormuz who had participated in the Portuguese-Gujarati War of 1531–34.[6] The Portuguese fortress housed about 3,000 people, of which solely 600 were soldiers.

First attacks

Under the command of Khadjar Safar – Coge Sofar in Portuguese, an Italian renegade from Otranto and an influential lord in Gujarat[14] – the Gujarati forces began crossing the channel of Diu onto the western side of the island on June 26, 1538, being held back by the city's western walls just long enough for the Portuguese to fill their water reserves and burn their supply storages in the city before finally retreating to the fortress on the eastern end of the island.

For the following two months the Gujaratis were unable to threaten the besieged with more than a low-intensity bombardment, while the Portuguese conducted occasional raids on the Gujarati positions.

Lopo de Sousa Coutinho, who would later write his memoirs on the siege, distinguished himself in August 14 after leading 14 Portuguese in a sortie into the city to capture supplies, defeating 400 soldiers of Khadjar Safar.

On September 4, the Ottoman fleet arrived in Diu, catching the Portuguese garrison by surprise and thus blockading the fortress by sea.[4] Captain da Silveira immediately sent a small craft to run the blockade with a distress call to Goa, while Pasha Suleiman promptly landed 500 janissaries, who proceeded to plunder the city – causing Suleiman to fall out of favour with the lords of Gujarat but Khadjar Safar.[15] The janissaries then attempted to scale the fortress' walls but were repelled with 50 dead. In September 7, a strong storm fell upon Diu, damaging part of the Ottoman fleet (and helping the Portuguese restore their water supplies), after which the Turks began unloading their artillery and a further 1000 men, and raising a number of defensive and siege works around the fort. It seems by then the Gujarati lords became distrustful of the Ottomans, possibly fearing that they might establish themselves in Diu after expelling the Portuguese, and the following day refused to provide any further supplies.[15]

On September the 14th, four foists from Goa and Chaul arrived with reinforcements.

A distant eyewitness, the famous Portuguese traveler Fernão Mendes Pinto later recounted how, passing by the fortress, Turkish galleys came close to seizing the tradeship he traveled in:

Having decided to stop for news of what was going on there, we began our approach to land, and by nightfall we were able to distinguish a lot of fires all along the coast and the occasional burst of artillery. Not knowing what to make of it, we shortened sail and hove for the rest of the night until daybreak, when we got a clear view of the fortress sorrounded by an enourmous number of lateen-rigged vessels. [...] While we were arguing back and forth and becoming gradually more alarmed by the possibilities confronting us, five ships moved out from the middle of the fleet. They were huge galleys, with their fore and aft sails in a checkerboard pattern of green and purple, the deck awnings literally covered in flags, and long banners streaming so far down from the mastheads that the ends brushed the surface of the water.[16]

— Fernão Mendes Pinto, in Peregrinação

The Ottoman artillery opened fire on the fortress on the 28th, as their galleys bombarded it from the sea, with the Portuguese replying suit – The Portuguese sank a galley but lost several men as two of their basilisks exploded.[17]

Attack on the Village of the Rumes' Redoubt

Across the Diu channel on the mainland shore, the Portuguese kept a redoubt by a village dubbed Vila dos Rumes – "Village of the Rumes" (Turks) modern day Gogolá – commanded by captain Francisco Pacheco and defended by 30–40 Portuguese, which came under attack by Gujarati forces. In September 10 the army of Khadjar Safar bombarded the fortlet with Turkish artillery pieces before attempting to assault it with the aid of janissaries but were repelled.

Khadjar Safar then ordered a craft be filled with timber, sulphur and tar, with which he hoped to place by the redoubt and smoke the Portuguese out. Realizing his intentions, António da Silveira sent Francisco de Gouveia with a small crew on a craft to burn the device with fire bombs under cover from the night, despite coming under enemy fire.[18] Another assault on September 28 with 700 janissaries failed after a prolonged bombardment.

The Portuguese garrison resisted until its captain Pacheco agreed to surrender to the Pasha on October 1, who had granted them safe passage to the fortress unarmed. When they surrendered however, Suleiman promptly had them imprisoned on his galleys and forced Pereira to write a letter to captain António da Silveira advising him to surrender.[19]

Pasha Suleiman's ultimatum and the reply of António da Silveira

With the redoubt of the Village of the Rumes conquered, Suleiman Pasha personally wrote an additional message the following day to captain da Silveira – passed through a Portuguese renegade – in which he instigated the Portuguese to surrender, claiming that he had with him veteran troops from the conquest of Rhodes, Belgrade and Hungary, and that the Portuguese resembled "cattle trapped in their pen". To which da Silveira then dictated out-loud his reply to be sent to the Pasha, ahead of the whole fortress:

Most honored captain Pasha. I have seen the words in your letter, and that of the captain which you have imprisoned through lie and betrayal of your word, signed under your name; which you have done because you are no man, for you have no balls, you are like a lying woman and a fool. How do you intend to pact with me, if you committed betrayal and falsity right before my eyes? For I take you in no account, for you are a traitor like a Jew. When I saw your armada, I feared you could do me harm; but now I am assured, for like a Jew you lie, so did those who took Rhodes and Belgrade, because they were scared of battle; and if at Rhodes were the knights that are in this pen, it would not have been taken. Be assured that here are Portuguese accustomed to killing many moors, and they have as captain António da Silveira, who has a pair of balls stronger than the cannonballs of your basilisks, that there's no reason to fear someone who has no balls, no honor and lies like a Jew. The pen before you has such cattle that already you are scared and arranging a pact to betray; such pact, should I accept it, these knights would throw me at sea, and defend it themselves.

— Captain António da Silveira[20]

Enraged by such a reply, the Pasha immediately ordered the bombardment of the fortress.

Assault on the fortress

By October 5, the Turks had finished their siege works and assembled all their artillery, which included nine basilisks, five great bombards, fifteen heavy guns and 80 medium and smaller cannon[21] that bombarded the fortress for the following 27 days. That night, 5 more craft from Goa with gunpowder and reinforcements arrived. After seven days of bombardment, part of the bulwark of Gaspar de Sousa collapsed and the Turks attempted to scale it "with two banners", but were repelled with heavy losses to bombs and arquebus fire. Another assault the following morning was met with equally fierce resistance by the Portuguese. Afterwards, the Turks forced labourers into the moat to undermine the fortress' walls and, in spite of several losses, managed to open a breach with gunpowder, but already the Portuguese had raised a barricade around the breach from the inside, which caused many losses on the assailants once they attempted to break through.[22] When at night the bombardment ceased, the Portuguese repaired the fortress' walls under cover from the darkness.

From an artillery battery on the opposite shore, the Turks bombarded the "Sea Fort" (Baluarte do Mar) that stood in the middle of the river mouth bombarding the flank of Muslim positions. In October 27, Suleiman Pasha ordered 6 small galleys to attempt and scale the fortlet, but came under heavy Portuguese cannon fire. The following day, the Turks drew 12 galleys and again attempted to "board" the fortlet, but were repelled with heavy losses due to fire bombs.[23]

In October 30, Pasha Suleiman attempted a final diversion by faking the withdrawal of his forces, embarking 1000 men. Ever cautious, António da Silveira ordered the sentries to be alert – at daybreak, 14,000 men divided in three "banners" attempted to scale the fortress as it was bombarded with no regard to friendly fire. A few hundred troops managed to scale the walls and raise banners but the Portuguese managed to repel the assailants, killing 500 and wounding a further 1000 from gunfire and bombs out of the São Tomé bastion.

With his relation with Coja Safar and the Gujaratis degrading and increasingly fearful of being caught off-hand by the Viceroy's armada, on November 1 the Pasha finally decided to abandon the siege and began reembarking his troops. Suspecting another ruse from the Pasha, captain Silveira ordered 20 of his last men on a sortie to deceive the enemy of their dwindling forces. The party managed to capture a Turkish banner.

The Pasha however, intended on departing on November 5, but was unable due to unfavourable weather. That night, two small galleys reached Diu with reinforcements and supplies, firing their guns and signal rockets. The following morning, a fleet of 24 small galleys was sighted and believing it to be the vanguard of the governor's rescue fleet, the Pasha hurriedly departed, leaving 1200 dead and 500 wounded behind. Khadjar Safar then set fire to his encampment and abandoned the island with his forces shortly after. In reality, it was just a forward fleet under the command of António da Silva Meneses and Dom Luís de Ataíde, dispatched from Goa with reinforcements, supplies and news that the governor would depart soon to their aid. Although they took no part in the fighting, the small force was triumphantly received within the ruined fortress by its last survivors. The Portuguese were by then critically low on gunpowder and supplies and with less than 40 valid men; in final stages of the siege, the Portuguese record that even the women assisted in its defence.[24]

Goa

The craft sent by António da Silveira arrived in Goa in mid September, but already governor Nuno da Cunha was well aware of the presence of the Turks in India: the Portuguese had intercepted a Turkish galleon in southern India and another galley that got separated from the fleet and called at Honavar, which the Portuguese destroyed with the aid of the locals (a fight in which Fernão Mendes Pinto participated). The governor had assembled a relief force of 14 galleons 8 galleys, several caravels and over 30 smaller oar ships, but in September 14 the new viceroy appointed by Lisbon arrived, and demanded the immediate succession in office.[25]

By the end of 1537, reports on Ottoman preparations in Egypt had reached Lisbon through Venice, and King John III promptly ordered a reinforcement of 11 naus and 3,000 soldiers, of which 800 were fidalgos, to be dispatched to India as soon as possible along with the new viceroy, Dom Garcia de Noronha. At Goa however, Dom Garcia considered the relief force organized by governor Nuno da Cunha to be insufficient, though the Portuguese veterans in India argued otherwise. The viceroy remained in Goa for two more months, organizing his forces until he had gathered an imposing fleet of 17 galleons, 15 carracks, 7 caravels, 8 galleys, 33 small oar ships and 30 support craft, with an estimated force of 5,000 Portuguese soldiers and several thousands of "fighting slaves" (escravos de peleja) and malabarese sailors and auxiliaries. Just as the expedition was about to set sail to Diu however, a craft arrived in Goa with the information that the siege had been lifted.[26]

Aftermath

After the failed siege, the Ottomans returned to Aden, where they fortified the city with 100 pieces of artillery.[27] One of them is still visible today at the Tower of London, following the capture of Aden by British forces in 1839.[28] Suleiman Pasha also established Ottoman suzerainty over Shihr and Zabid, and reorganized the territories of Yemen and Aden as an Ottoman province, or Beylerbeylik.[4]

The veteran Lopo de Sousa Coutinho later recounted that "it was said" that the Portuguese who had surrendered to Suleiman Pasha were all killed off in the Red Sea, on their way back to Egypt. Indeed, at As-Salif, by Kamaran Island, the Pasha had all prisoners under his control massacred, 140 in total, and their heads put on display in Cairo.[29]

Suleiman Pasha intended to launch a second expedition against the Portuguese in Diu, but this did not happen.[4] In 1540, the Portuguese sent a retaliatory expedition to Suez with a fleet of 72 ships, sacking Suakin, Kusayr, and spreading panic in Egypt.[4][30] In 1546, the Ottoman established a new naval base in Basra, thus threatening the Portuguese in Hormuz.[4] The Ottomans would suffer a strong naval defeat against the Portuguese in the Persian Gulf in 1554.[4] Further conflict between the Ottomans and the Portuguese would lead to the Ottoman expedition to Aceh in 1565.

The Indians would not retake possession of the Diu enclave until Operation Vijay in 1961.[31]

Gallery

The gateway of the outer walls of Diu.

The gateway of the outer walls of Diu. The siege of Diu by the "Arabians"

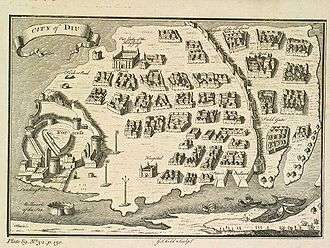

The siege of Diu by the "Arabians" Map of Diu, 1729.

Map of Diu, 1729. An 18th century depiction of the Siege of Diu

An 18th century depiction of the Siege of Diu Ottoman fleet in the Indian Ocean in the 16th century

Ottoman fleet in the Indian Ocean in the 16th century Primitive inner wall and moat

Primitive inner wall and moat View within the walls

View within the walls Sea Fort, nowadays known as Panikota, as seen from the citadel

Sea Fort, nowadays known as Panikota, as seen from the citadel- São Jorge bastion

Sea wall

Sea wall Gate

Gate Moat

Moat Inner and outer walls

Inner and outer walls Cannon of Hadım Suleiman Pasha, taken in the capture of Aden in 1839, now in the Tower of London.

Cannon of Hadım Suleiman Pasha, taken in the capture of Aden in 1839, now in the Tower of London.- Portuguese cannon in Diu, inscribed with the arms of Portugal

See also

Notes

- ↑ Asiatic Society of Bombay: Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay (Edition 25), The Society, 1922, page 316.

- ↑ Gonçalo Feio (2013), O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra p.114

- 1 2 Gaspar Correia (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV pp.868–870.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire by Halil İnalcik p.324ff

- 1 2 Churchill: A Collection of Voyages and Travels: Some Now First Printed from Original Manuscripts, Awnsham and John Churchill, 1704, page 594.

- 1 2 Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelo Portugueses 1833 edition, Lisboa Typographia Rollandiana, book VIII p.20

- 1 2 The Cambridge history of the British Empire, Volume 2 by Arthur Percival Newton p.14

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538, p.332

- ↑ Tarikh al-Shihri, in SERJEANT, Robert Bertram (1963). The Portuguese off the South Arabian Coast Clarendon Press, p. 79

- ↑ Gaspar Correia (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV pp.868–870. Gaspar Correia states to have gotten this information from a "Christian rower that fled to Diu from the galleys"

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538, p.331

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538, p.321-323

- ↑ Nicola Melis, "The chronicle of Lopo de Sousa Coutinho as a major source of the first siege of Diu", in "The Indian Ocean and the Presence of the Ottoman Navy in the 16th and 17th Centuries", edited by Naval Forces Staff, Naval Printing House, Istanbul 2009, part III, pp. 15–25.

- ↑ "Cosa Zaffer" in RAMUSIO, Giovanni Battista (1550–1606) Navigazioni e Viaggi Turin, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1978 edition, p.684

- 1 2 Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538, p.325

- ↑ Fernão Mendes Pinto: The Travels of Fernão Mendes Pinto translated edition 1989, University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Lopo de Sousa Coutinho O Primeiro Cerco de Diu Lisboa, Publicações Alfa, 1989 edition, p.130 – According to Coutinho, a witness, the Portuguese accidentally swapped the gunpowder barrels, using finer gunpowder meant for arquebuses instead of cruder gunpowder for the cannon, causing them to explode, killing 4 men

- ↑ Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses, 1833 edition, Lisbon, Typographia Rollandiana, book VIII p.448

- ↑ Correia, Gaspar (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV chapter XI pp.29–35

- ↑ Portuguese: " Muyto honrado capitão bayxá. Bem vy as palavras de tua carta e do capitão do baluarte, que tens cativo per trayção e mentira de tua palavra, affirmada com tua chapa; o que fizeste porque nom hes homem pois não tens c... que és como molher mentirosa, e de pouco saber. Como me cometes que faça contigo concerto, pois diante de meus olhos fizeste traição e falsidade? Polo que nom tenho em nenhuma conta, porque de judeu he seres trédor. Eu quando vy tu'armada, e atégora, temi que me podias fazer algum dano; mas agora já estou seguro, porque de homem judeu he fazeres traição, e assy o fizeram os que tomaram Rodes e Belgrado, porque per batalha houveram medo; e se em Rodes estiveram os cavalleiros que estão aqui n'este curral, desengana-te que ele nom fora tomado. E sabe por certo que aqui estão portuguese acostumados a matar muytos mouros e que têm por capitão António da Silveira, que tem um par de c... mais fortes que os pelouros dos seus basaliscos, que nom ha medo nenhum a que nom tem c... nem verdade e de judeu faz traição; o curral diante de ti está, com tal gado que já lhe tens medo e cometes concerto para fazer trayção; o qual concerto, indaque o eu quisesse fazer, aquy estão taes cavalleiros que me deitarião ao mar e eles lho defenderiam." In Gaspar Correia (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV p.35

- ↑ Lopo de Sousa Coutinho (1556) O Primeiro Cerco de Diu Lisboa, Publicações Alfa, 1989 edition, p.148

- ↑ Gaspar Correia (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV pp.37–39

- ↑ Gaspar Correia (1558–1563) Lendas da Índia, 1864 edition, Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, book IV pp.42–45

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538 p.330

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538 p.331

- ↑ Saturnino Monteiro (1995) Portuguese Sea Battles – Volume II – Christianity, Commerce and Corso 1522–1538 p.332-334

- ↑ An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire by Halil İnalcik p.326

- ↑ Tower of London exhibit

- ↑ Tarikh al-Shihri, in SERJEANT, Robert Bertram (1963). The Portuguese off the South Arabian Coast Clarendon Press, p. 86

- ↑ Mecca: a literary history of the Muslim Holy Land by Francis E. Peters p.405

- ↑ McGregor, Andrew James A military history of modern Egypt: from the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War; p. 30