Siege of Sevastopol (1854–55)

| Siege of Sevastopol | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crimean War | |||||||

Siege of Sevastopol by Franz Roubaud | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total casualties: 102,000 killed, wounded, and died from disease[8] | ||||||

The Siege of Sevastopol (at the time called in English the Siege of Sebastopol) lasted from October 1854 until September 1855, during the Crimean War. The allies (French, Ottoman, and British) landed at Eupatoria on 14 September 1854, intending to make a triumphal march to Sevastopol, the capital of the Crimea, with 50,000 men. The 56-kilometre (35 mi) traverse took a year of fighting against the Russians. Major battles along the way were Alma (September 1854), Balaklava (October 1854), Inkerman (November 1854), Tchernaya (August 1855), Redan (September 1855), and, finally, Sevastopol (September 1855). During the siege, the allied navy undertook six bombardments of the capital, on 17 October 1854; and on 9 April, 6 June, 17 June, 17 August, and 5 September 1855.

Sevastopol is one of the classic sieges of all time.[9] The city of Sevastopol was the home of the Tsar's Black Sea Fleet, which threatened the Mediterranean. The Russian field army withdrew before the allies could encircle it. The siege was the culminating struggle for the strategic Russian port in 1854–55 and was the final episode in the Crimean War.

During the Victorian Era, these battles were repeatedly memorialized. The Siege of Sevastopol was the subject of Crimean soldier Leo Tolstoy's Sebastopol Sketches and the subject of the first Russian feature film, Defence of Sevastopol. The Battle of Balaklava was made famous by Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem "The Charge of the Light Brigade" and Robert Gibb's painting The Thin Red Line. A panorama of the siege itself was painted by Franz Roubaud.

The Jamaican and English nurses who treated the wounded during these battles were much celebrated, most famously Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale.

Description

The allies (French, Ottoman, and British) landed at Eupatoria on 14 September 1854.[10] The Battle of the Alma (20 September 1854), which is usually considered the first battle of the Crimean War (1853–1856), took place just south of the River Alma in the Crimea.[11] An Anglo-French force under Jacques Leroy de Saint Arnaud and FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan defeated General Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov's Russian army, which lost around 6,000 troops.[12]

Moving from their base at Balaklava at the start of October, French and British engineers began to direct the building of siege lines along the Chersonese uplands to the south of Sevastopol.[13] The troops prepared redoubts, gun batteries, and trenches.[14]

With the Russian army and its commander Prince Menshikov gone, the defence of Sevastopol was led by Vice Admirals Vladimir Alexeyevich Kornilov and Pavel Nakhimov, assisted by Menshikov's chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Eduard Totleben.[15] The military forces available to defend the city were 4,500 militia, 2,700 gunners, 4,400 marines, 18,500 naval seamen, and 5,000 workmen, totalling just over 35,000 men.

The Russians began by scuttling their ships to protect the harbour, then used their naval cannon as additional artillery and the ships' crews as marines.[16] Those ships deliberately sunk by the end of 1855 included Grand Duke Constantine, City of Paris (both with 120 guns), Brave, Empress Maria, Chesme, Yagondeid (84 guns), Kavarna (60 guns), Konlephy (54 guns), steam frigate Vladimir, steamboats Thunderer, Bessarabia, Danube, Odessa, Elbrose, and Krein.

By mid-October 1854, the Allies had some 120 guns ready to fire on Sevastopol; the Russians had about three times as many.[17]

On 5 October 1854 (old style date, 17 October new style)[lower-alpha 1] the artillery battle began.[18] The Russian artillery first destroyed a French magazine, silencing their guns. British fire then set off the magazine in the Malakoff redoubt, killing Admiral Kornilov, silencing most of the Russian guns there, and leaving a gap in the city's defences. However, the British and French withheld their planned infantry attack, and a possible opportunity for an early end to the siege was missed.

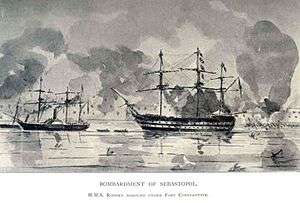

At the same time, to support the Allied land forces, the Allied fleet pounded the Russian defences and shore batteries. Six screw-driven ships of the line and 21 wooden sail were involved in the sea bombardment (11 British, 14 French, and two Ottoman Turkish). After a bombardment that lasted over six hours, the Allied fleet inflicted little damage on the Russian defences and coastal artillery batteries while suffering 340 casualties among the fleet. Two of the British warships were so badly damaged that they were towed to the arsenal in Constantinople for repairs and remained out of action for the remainder of the siege, while most of the other warships also suffered serious damage due to many direct hits from the Russian coastal artillery. The bombardment resumed the following day, but the Russians had worked through the night and repaired the damage. This pattern would be repeated throughout the siege.

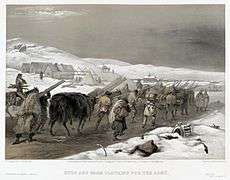

During October and November 1854, the battles of Balaclava[19] and Inkerman[20] took place beyond the siege lines. Balaclava gave the Russians a morale boost and convinced them that the Allied lines were thinly spread out and undermanned.[21] But after their defeat at Inkerman,[22] the Russians saw that the siege of Sevastopol would not be lifted by a battle in the field, so instead they moved troops into the city to aid the defenders. Toward the end of November, a winter storm ruined the Allies' camps and supply lines. Men and horses sickened and starved in the poor conditions.

While Totleben extended the fortifications around the Redan bastion and the Malakoff redoubt, British chief engineer John Fox Burgoyne sought to take the Malakoff, which he saw as the key to Sevastopol. Siege works were begun to bring the Allied troops nearer to the Malakoff; in response, Totleben dug rifle pits from which Russian troops could snipe at the besiegers. In a foretaste of the trench warfare that became the hallmark of the First World War, the trenches became the focus of Allied assaults.

The Allies were able to restore many supply routes when winter ended. The new Grand Crimean Central Railway, built by the contractors Thomas Brassey and Samuel Morton Peto, which had been completed at the end of March 1855[23] was now in use bringing supplies from Balaclava to the siege lines. The railroad delivered more than five hundred guns and plentiful ammunition.[23] The Allies resumed their bombardment on 8 April 1855 (Easter Sunday). On 28 June (10 July), Admiral Nakhimov died from a head wound inflicted by an Allied sniper.[24]

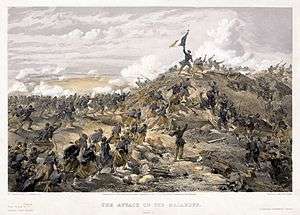

On 24 August (5 September) the Allies started their sixth and the most severe bombardment of the fortress. Three hundred and seven cannon fired 150,000 rounds, with the Russians suffering 2,000 to 3,000 casualties daily. On 27 August (8 September), thirteen Allied divisions and one Allied brigade (total strength 60,000) began the last assault. The British assault on the Great Redan failed, but the French, under General Mac-Mahon, managed to seize the Malakoff redoubt and the Little Redan, making the Russian defensive position untenable. By the morning of 28 August (9 September), the Russian forces had abandoned the southern side of Sevastopol.[8][25]

Although defended heroically and at the cost of heavy Allied casualties, the fall of Sevastopol would lead to the Russian defeat in the Crimean War.[1] Most of the Russian casualties were buried in Brotherhood cemetery in over 400 collective graves. The three main commanders (Nakhimov, Kornilov, and Istomin) were interred in the purpose-built Admirals' Burial Vault.

Battles during the siege

- Skirmish at River Bulganek (19 September 1854)

- Battle of Alma (20 September 1854)

- First bombardment of Sevastopol (17 October 1854)

- Battle of Balaclava (25 October 1854)

- Battle of Little Inkerman (26 October 1854)

- Battle of Inkerman (5 November 1854)

- Aborted Russian attack at Balaklava (10 January 1855)

- Battle of Eupatoria (17 February 1855)

- Aborted allied attack at Chernaya (20 February 1855)

- Russian army assaults and seizes the Mamelon (22 February 1855)

- French assault on the "White Works" repulsed (24 February 1855)

- Second bombardment of Sevastopol (9 April 1855)

- British assault "the Rifle Pits" successfully (19 April 1855)

- Battle of the Quarantine Cemetery (1 May 1855)

- Third bombardment of Sevastopol (6 June 1855)

- Allies successfully assault the "White Works", Mamelon and "The Quarries" (8-9 June 1855)

- Fourth bombardment of Sevastopol (17 June 1855)

- Allied assaults on the Malakoff and Great Redan repulsed (18 June 1855)

- Battle of the Chernaya (16 August 1855)

- Fifth bombardment of Sevastopol (17 August 1855)

- Sixth bombardment of Sevastopol (7 September 1855)

- Allies assault the Malakoff, Little Redan, Bastion du Mat and the Great Redan (8 September 1855)

- Russians retreat from Sevastopol on 9 September 1855

Fate of Sevastopol cannon

The British sent a pair of cannons seized at Sevastopol to each of several important cities in the Empire.[26][27] Additionally, several were sent to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. These cannon are now all kept at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (renamed after the closing of RMA Woolwich shortly after the Second World War) and are displayed in front of Old College, next to cannon from Waterloo and other battles.

The cascabel (the large ball at the rear of old muzzle-loaded guns) of several cannon captured during the siege was said to have been used to make the British Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the British Armed Forces. However, Hancocks, the manufacturer, confirms that the metal is Chinese, not Russian, bronze. The cannons used are in the Firepower Museum in Woolwich and are clearly Chinese. There would be no reason why Chinese cannon would be in Sevastopol in the 1850s and it is likely that the VC guns were, in fact, British trophies from the China war in the 1840s held in the Woolwich repository. Though it had been suggested that the VCs should be made from Sevastopol cannons, it seems that in practice, they were not. Testing of medals which proved not to be of Russian bronze has given rise to stories that some Victoria Crosses were made of low grade material at certain times but this is not so - all Victoria Crosses have been made from the same metal from the start.

Bath Cannon

Was melted down in the Second World War.

Bearsden Cannon

A cannon was found in the garden of a house in Bearsden in 2017. It was postulated it might be one of the two missing Glasgow cannon. (see https://www.milngavieherald.co.uk/news/history-buffs-solve-the-mystery-of-the-cannon-1-4407874)

Berwick Cannon

Is kept at Fisher's Fort and recently underwent restoration by English Heritage. The cannon was made in 1826, and was given to Berwick in 1858. The cannon displays a Russian double-headed eagle on its barrel. The gun was the only one to survive the great scrappage of the Second World War in Berwick.

Bridgnorth

Melted down in Second World War.

Cambridge, Ontario Cannon

One cannon was sent to the city of Galt, Ontario, Canada (now renamed Cambridge), where it is still on display in Queen's Square with an inscription describing its origin, year of capture (1859) and installation (1862). It is known locally as 'the Russian Gun'. In December 1864 the Russian Gun arrived at the Galt railway station, where reports of the day claim it attracted 'considerable attention'. The gun was initially mounted on a wooden carriage and put on display in Queen’s Square. In 1866, a group decided to cap off the town’s Victoria Day celebrations with 'a royal salute of 21 guns fired from the Russian Gun'. The gun was taken from Queen’s Square to the top of the hill overlooking Dickson Park. In A part of our Past: Essays on Cambridge’s history the story goes: 'Mr. (William) Boge was assisted by Mr. James Armstrong, who attended to the ramming of the muzzle loading the gun, and by Mr. David Galletly who was working the vent of the gun. Three rounds had been safely fired when the powder for the fourth round was placed in the muzzle. Next came the wadding, which consisted of sod, with Mr. Boge and Mr. Armstrong ramming it home. Suddenly and unexpectedly a fearful roar rent the holiday air as the powder exploded prematurely.” The account goes on to say Boge and Armstrong were blown seven yards from the mouth of the gun. Both were disfigured. Three other people were injured in the blast including Galletly, whose hand was burned, and two boys who were bystanders. They were both struck in the face and cut by flying debris. The two men who died were both members of the Galt Fire Brigade. The cannon was left at the top of the hill in Dickson Park for several weeks before being returned to Queen’s Square, never to be fired again. In May 1910 the Daughters of the Empire had the Russian Gun remounted on the concrete base where it sits today.

Chelmsford Cannon

The Chelmsford Cannon was kept in the High Street between 1858 and 1937 and was then moved to a corner of the park. In 1908 some apprentices fired it, causing windows to be broken. It is now plugged.

Cheltenham Cannon

Was melted down in Second World War.

Congleton Cannon

The cannon arrived at Congleton Station on 14 June 1859 and was escorted into the town in an ‘immense procession’ led by five men who had fought in the Crimea war. At first the cannon was placed on a specially built platform situated either at the bottom of Moody Street on an open space now outside the Royal bank of Scotland or on the other side of the street in front of ‘Mr Deakin’s shop’. By 1871 it seems to have become an anachronism and the opening of the park seemed to be a suitable opportunity to move it to a mock fort emplacement at the top of the Park wood. During the Second World War the demand for metal led to a debate by the Town Council for the cannon to be donated to help the war effort.

Darlington Cannon

The Darlington Cannon is kept in South Park.

Derby Cannon

Was melted down in Second World War.

Dundee Cannon

Dundee is known to have refused a cannon when offered, because of the cost of mounting it.

Dunfermline Cannon

Received a cannon but it was melted down during the Second World War.

Ely Cannon

Ely keeps its cannon on Palace Green, west of the Cathedral. The inscription reads: 'Russian cannon captured during the Crimean War and presented to the people of Ely in 1860 by Queen Victoria to mark the creation of the Ely Rifle Volunteers'. The serial number is 8726

Evesham Cannon

Evesham was given one in 1855. It is now housed in the Almonry Museum and Heritage Centre.

Georgetown, Guyana

Two Russian cannon were given to Georgetown and now sit outside the parliament building.

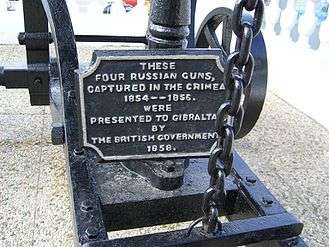

Gibraltar Cannon

Four Russian guns were presented to Gibraltar in 1858.

Glasgow Cannon

Was given 2 cannon. They were thought to be melted down in Second World War.

Halifax Cannon

Two cannon were sent to Halifax. They are believe to have been melted down.

Hartlepool Cannon

Kept on the Heugh Headland. The inscription says: 'The cannon was captured from the Russian Army at the Battle of Sebastopol during the Crimean War (1854-56). In 1857, the then Secretary of State, Lord Panmure, offered the cannon to Hartlepool Borough Council who gratefully accepted it. It was transported from London on the steam ship 'Margaret', at a total cost of £2.19s.3d and after a year's delay, arrived at Hartlepool in September 1858.'

Hereford Cannon

Was melted down in Second World War.

Huntingdon Cannon

The Huntingdon cannon was melted down during World War II, and is now replaced with a replica (made 1990).

Leominster Cannon

Was melted down in Second World War.

Lichfield Cannon

Melted down in Second World War.

Lisburn Cannon

The inscription on the Lisburn cannon says: 'A Russian cannon taken at Sebastopol during the Crimean War (1853 to March 1856). Presented to Lisburn by Admiral Henry Meynell (c.1785–1863) RN in 1858. Lisburn, Co. Antrim, Ireland.'

Ludlow Castle cannon

Was threatened with being melted for scrap in Second World War, but the council melted other cannon and metal and kept back the Russian cannon.

Middlesbrough Cannon

Its cannon is kept in Albert Park.

Monmouth Cannon

Is on display at the Royal Monmouthshire Royal Engineers Museum, Monmouth, Wales.

Newry Cannon

Known as: 'The Russian Trophy' it is kept on Bank Parade, Newry. It sits outside the Polish Consulate, pointing upriver. The barrel sports the Russian Eagle crest.

New South Wales

New South Wales received 2 cannon in recognition of the funds donated to the Patriotic Fund to assist the war effort. The 2 cannon are now in Centennial Park in Sydney. Originally, the flanked Governor Bourke’s statue in The Domain in Sydney (near the old Bent Street entrance). They were relocated in 1920 to Centennial Park and mounted on a rise.

Nottingham Cannon

Kept in Nottingham Arboretum.

Ontario Cannon

Are displayed in Victoria Park, London (Ontario). There is an inscription which says the following: 'These cannon were used at the siege of Sebastopol and were brought to this country after the capture of that city by the Britishin 1855. Sir John Carling was instrumental in procuring these three pieces for this city. This gun is a British piece. The other two are Russian. This tablet was erected by the London and Middlesex Historical Society. 1907. Restored 1987'

Portsmouth Cannon

Melted down in Second World War.

Preston Cannon

The two Preston Cannon seemed to have survived the war and been lost during the 1960s. The council commissioned two new replicas in 2008 at a cost of £350,000.

Retford Cannon

There is a cannon on display in Cannon Square in Retford Nottinghamshire. A plaque on the side of the cannon reads: Captured 1855 at Sevastopol. This is an original cannon and was hidden during World War II when it was threatened with being melted down for scrap. It sits in front of the main church, just off the Market Square. The monument is listed (Grade II) to include the Sevastopol Cannon, Lamp arch, supporting plinth and iron posts with chains surrounding it.

St Peter Port, Guernsey

Is on display at Castle Cornet. Bears a plaque that says: 'Presented by Her Majesty's Government to the Island of Guernsey as a trophy of the Russian War 1856'.

Tasmania Cannon

Received two cannon.

Toronto Cannon

Toronto received a fine pair of Sevastopol cannons. They installed them in 1860 in a new park, which was officially named Queen’s Park in honour of Victoria. William Denby, in his wonderful book Lost Toronto, tells us that the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was on hand to lay a cornerstone to Queen Victoria. Sculptor Marshall Wood created a statue of Queen Victoria. It was finally unveiled in 1871, with the Sevastopol cannons on either side. But in 1874, when Wood submitted his invoice for $7,500, city officials were taken aback; they apparently hadn’t realized the City would be asked to foot the bill – and such a high one at that! So they removed the statue and moved the cannons, which had formerly stood on the spot where there’s now a John A. Macdonald statue, to their current positions on either side of the main entranceway to the Legislative Buildings. A new, less costly statue, was commissioned and installed in 1902.

Victoria

Received two cannon.

Woolwich Cannon

Cannon were stored in the arsenal at Woolwich.

Wootton Basset Cannon

Cannon was melted down in Second World War.

Wrexham Cannon

Melted down in Second World War.

Other known locations Cannon Were Sent

Ulster Cannon

Ennis County Clare

Rochester

Lewes Castle

Armagh

Maidstone

Edinburgh

Gallery

Newry Cannon 2009

Newry Cannon 2009 Gibraltar

Gibraltar Gibraltar (2)

Gibraltar (2) Middlesbrough cannon

Middlesbrough cannon Monmouth gun

Monmouth gun Ely

Ely Ontario gun

Ontario gun.jpg) Georgetown, Guyana cannon

Georgetown, Guyana cannon_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1231250.jpg) Berwick cannon

Berwick cannon Nottingham cannon

Nottingham cannon Replacement cannon in Huntingdon

Replacement cannon in Huntingdon Armagh cannon

Armagh cannon Toronto cannon

Toronto cannon- Ennis cannon

Ludlow Castle cannon

Ludlow Castle cannon Galt cannon (now Cambridge, Ontario)

Galt cannon (now Cambridge, Ontario) Hartlepool cannon

Hartlepool cannon Gibraltar plaque

Gibraltar plaque.jpg) Maidstone cannon

Maidstone cannon Guernsey cannon

Guernsey cannon

Gallery

Bombardment of Sevastopol by HMS Rodney, Crimean War (October 1854)

Bombardment of Sevastopol by HMS Rodney, Crimean War (October 1854) British lithograph published March 1855, after a water-colour by William Simpson, shows winter military housing under construction with supplies borne on soldiers' backs. A dead horse, partially buried in snow, lies by the roadside.

British lithograph published March 1855, after a water-colour by William Simpson, shows winter military housing under construction with supplies borne on soldiers' backs. A dead horse, partially buried in snow, lies by the roadside. A view of the "Valley of the Shadow of Death" near Sevastopol, taken by Roger Fenton in March 1855. It was so named by soldiers because of the number of cannonballs that landed there, falling short of their target, during the siege.[28]

A view of the "Valley of the Shadow of Death" near Sevastopol, taken by Roger Fenton in March 1855. It was so named by soldiers because of the number of cannonballs that landed there, falling short of their target, during the siege.[28].jpg) Captain Julius Robert's Mortar Boats engaging the quarantine battery – Sebastopol August 15, 1855 - Lithograph T.G.Dutton

Captain Julius Robert's Mortar Boats engaging the quarantine battery – Sebastopol August 15, 1855 - Lithograph T.G.Dutton Attack on the Malakoff by William Simpson

Attack on the Malakoff by William Simpson Siege of Sevastopol 1855 by Grigoryi Shukaev

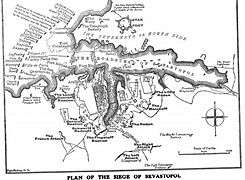

Siege of Sevastopol 1855 by Grigoryi Shukaev Map of Sevastopol

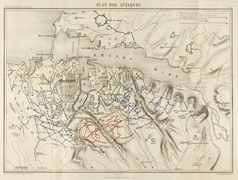

Map of Sevastopol Map of the French (blue) and British (red) lines during the siege. The defenders' positions are in green.

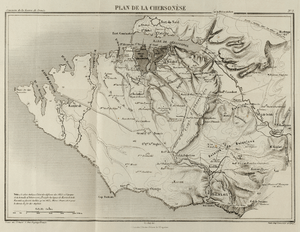

Map of the French (blue) and British (red) lines during the siege. The defenders' positions are in green. Supply lines from the port of Balaklava, 1855. The Grand Crimean Central Railway is shown as "Chemin de Fer Anglais"

Supply lines from the port of Balaklava, 1855. The Grand Crimean Central Railway is shown as "Chemin de Fer Anglais" Monument to the Scuttled Ships, Crimea, Sevastopol. The sculptor Amandus Adamson 1905

Monument to the Scuttled Ships, Crimea, Sevastopol. The sculptor Amandus Adamson 1905- Three 17th Century Russian Orthodox Church Bells in Arundel Castle, West Sussex United Kingdom. These bells were taken as trophies from Sevastopol at the conclusion of the Siege of Sevastopol.

- Three 17th Century Russian Orthodox Church Bells in Arundel Castle

- Three 17th Century Russian Orthodox Church Bells in Arundel Castle

The Sevastopol Monument in Halifax, Nova Scotia is the only Crimean War monument in North America.

The Sevastopol Monument in Halifax, Nova Scotia is the only Crimean War monument in North America.

See also

- Sebastopol Sketches, a cycle of three historical fiction short stories written by Leo Tolstoy

- Defence of Sevastopol, Russia's first feature film

Notes

- ↑ In this article the first date given is the old style date, the date following is the modern equivalent. Conversions were completed using Calendar Converter by John Walker.

References

- 1 2 Bellamy, Christopher (2001). Richard Holmes, ed. The Oxford Companion to Military History: Crimean War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866209-2.

- 1 2 Советская Военная Энциклопедия, М., Воениздат 1979, т.7, стр.279

- ↑ Maule, Fox (1908). The Panmure Papers. London: Hodder and Stoughton, quoted in David Kelsey's Crimean Texts. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009.

- ↑ David G. Chandler, Atlas of Military Strategy, Lionel Levental Ltd 1980, ISBN 0-85368-134-1, p.146

- ↑ Blake, The Crimean War, Pen and Sword 1971, p.114

- ↑ or 38,000: David G. Chandler, Atlas of Military Strategy, Lionel Levental Ltd 1980, ISBN 0-85368-134-1, p.145

- ↑ John Sweetman, Crimean War, Essential Histories 2, Osprey Publishing, 2001, ISBN 1-84176-186-9, p.89

- 1 2 Советская Военная Энциклопедия, М., Воениздат 1979, т.7, стр.280

- ↑ Elphinstone, H.C (2003). Siege of Sebastopol 1854–55: Journal of the Operations Conducted by the Corps of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (Picador Publishing: New York, 2010) p. 230.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, pp. 208-220.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 218.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 236.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 237.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 233.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 224.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 238.

- ↑ Orlando, Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 238.

- ↑ Engels, Frederick. The War in the East. The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. 13. pp. 521–527.

- ↑ Engels, Frederick. The Battle of Inkerman. The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. 13. pp. 528–535.

- ↑ Orlaando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 254.

- ↑ Frederick Engels, " The Battle of Inkerman" published on 27 November 1854 in the New York Herald and carried in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 13, pp. 528-535

- 1 2 Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 356.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History, p. 378.

- ↑ Troubetzkoy, Alexis S. (2006). The Crimean War: The Causes and Consequences of a Medieval Conflict Fought in a Modern Age. London: Constable & Robinson. p. 288.

- ↑ However, there has been controversy about the fate of two cannons that were sent to Halifax, West Yorkshire. As they were removed from a local park and sold for scrap. "Two 1799 Russian 24 Pdrs. Watch The St. Lawrence River In Quebec"

- ↑ "The Russian SBML 18-pr at Waiouru" Archived 5 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine., Royal New Zealand Artillery Association

- ↑ Grant, Simon (2005). A Terrible Beauty Archived 7 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. from Tate etc magazine, issue 5, accessed 2007-09-27

Further reading

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria's Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 0-75095-685-2.

External links

- Letters and Papers of Colonel Hugh Robert Hibbert (1828–1895) Mainly relating to service in the Crimean War, 1854–1855.

- Historical Dictionary of the Crimean War

- Henry Ottley. Remarkable Sieges: From The Siege Of Constantinople In 1453, To That Of Sebastopol, 1854 (1854). 2010.