Shantinatha

| Shantinatha | |

|---|---|

| 16th Jain Tirthankara, 5th Chakravartin, 11th Kamadeva | |

|

Seated image of Shantinatha with old Kannada inscription (1200 A.D.) engraved on the pedestal in Shantinatha Basadi, Jinanathapura | |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Dharmanatha |

| Successor | Kunthunatha |

| Symbol | Deer or Antelope |

| Height | 40 bows (120 metres) |

| Age | over 700,000 years |

| Color | Golden |

| Personal information | |

| Born | Hastinapur[1] |

| Died | Shikharji |

| Spouse | Yasomati |

| Parents |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

Shree Shantinatha was the sixteenth Jain Tirthankar of the present age (Avasarpini).[2] Shree Shantinatha was born to King Visvasen and Queen Achira at Hastinapur in the Ikshvaku dynasty. His birth date is the thirteenth day of the Jyest Krishna month of the Indian calendar. He was also a Chakravarti and a Kamadeva. He ascended to throne when he was 25 years old.[3][4] At the age of 50 years, he became a Jain monk and started his penance. According to Jain beliefs, he became a siddha, a liberated soul which has destroyed all of its karma.

Biography in Jain tradition

Birth

Shantinatha was born to King Visvasen and Queen Achira at Hastinapur in the Ikshvaku dynasty on thirteenth day of the Jyest Krishna month of the Indian calendar.[3] During his time epidemic of epilepsy broke out and he helped people to control it giving him name of Shantinath.[5]

Omniscience

Shanitnath was the fifth Chakravartin and ruled for 25 years after which he decided to spend his life as ascetic.[5] After one year of ascetism on the 9th bright day of month of Pausha (December/January), he achieved omniscience under a nandi tree.[3] The yaksha and yakshi of Shantinatha are Kimpurusha and Mahamanasi according to Digambara tradition and Garuda and Nirvani according to Śvētāmbara tradition.[6]

Moksha

His death is traditionally called by Jains as moksha or separation of soul from cycles of rebirths.[7] He died atop Shikharji on 13th day of the dark half of the month Jyestha (May–June),[3][note 1] known contemporaneously as the Parasnath Hills in northern Jharkhand.[10]

Previous births

- King Srisena

- Yugalika in Uttar Kurukshetra

- Deva in Saudharma heaven

- Amitateja, prince of Arkakirti

- Heavenly deva in 10th heaven Pranat (20 sagars life span)

- Aparajit Baldeva in East Mahavideha (life span of 84,00, 000 purva)

- Heavenly Indra in 12th heaven Achyuta (22 sagars life span)

- Vajrayudh Chakri, the son of Tirthankar Kshemanakar in East Mahvideha

- Heavenly deva in Navgraivayak heaven

- Megharath, the son of Dhanarath in East Mahavideh in the area where Simandharswami is moving at present

- Heavenly deva in Sarvartha Siddha Heaven (33 sagars life span)

Literature

- The Shantinatha Charitra, by Acharya Ajitprabhasuri, this text has been declared as a global treasure by UNESCO.[11]

- Shantipurana written in around 10th century by Sri Ponna.[12]

Legacy

Iconography

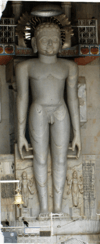

Shantinatha is usually depicted in a sitting or standing meditative posture with the symbol of a deer or antelope beneath him.[13][14] Every Tīrthankara has a distinguishing emblem that allows worshippers to distinguish similar-looking idols of the Tirthankaras.[15][16][17] The deer or antelope emblem of shantinath is usually carved below the legs of the Tirthankara. Like all Tirthankaras, Shantinath is depicted with Shrivatsa[note 2] and downcast eyes.[18]

Famous temples

- Shantinatha Temple, Khajuraho - a UNESCO World Heritage site

- Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur - birthplace of Shantinatha

- Shantinath Temple, Deogarh

- Shantinatha Basadi, Jinanathapura

- Shantinath Jain Teerth

- Aharji Jain Teerth

- Shantinath Jain temple, Kothara

- Shantinath Jain Temple in Leicester (first Jain Temple in Europe and the Western World) - Jainism in the United Kingdom[19]

'Singh Dwaar' of Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

'Singh Dwaar' of Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

Colossal statues

32 foot statue of Shantinath at Shantinath Jinalaya in Shri Mahavirji

32 foot statue of Shantinath at Shantinath Jinalaya in Shri Mahavirji.jpg) 31 foot statue of Shantinath at Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur

31 foot statue of Shantinath at Prachin Bada Mandir, Hastinapur 22½ foot statue of Shantinath at Bhojpur Jain Temple

22½ foot statue of Shantinath at Bhojpur Jain Temple- 15 foot image at Shantinatha temple, Khajuraho[21]

15 feet Shantinatha statue at Shantinath Basadi, Chandragiri

15 feet Shantinatha statue at Shantinath Basadi, Chandragiri

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shantinatha. |

Notes

- ↑ Some texts refer to the place as Mount Sammeta.[8] This place is revered in Jainism because 20 out of 24 Jinas died here.[9]

- ↑ A special symbol that marks the chest of a Tirthankara. The yoga pose is very common in Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. Each tradition has had a distinctive auspicious chest mark that allows devotees to identify a meditating statue to symbolic icon for their theology. There are several srivasta found in ancient and medieval Jain art works, and these are not found on Buddhist or Hindu art works.

References

- ↑ Tandon 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Tukol 1980, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 Jain 2009, p. 84.

- ↑ Shah, Chandraprakash. "SHRI SHANTINATH, 16TH TIRTHANKARA".

- 1 2 Mittal 2006, p. 689.

- ↑ Shah 1987, p. 152.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Jacobi 1964, p. 275.

- ↑ Cort 2010, pp. 130–133.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 13.

- ↑ Shāntinātha Charitra, UNESCO.

- ↑ Das 2005, p. 143.

- ↑ Doniger 1999, p. 550.

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 369.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Krishna 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 225.

- ↑ Moore 1977, p. 138.

- ↑ Wilson & Ravat 2017, p. 23.

- ↑ "Shantinatha Basti, Halebid". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Ali Javid; Tabassum Javeed (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-87586-482-2.

Sources

- Johnson, Helen M. (1931), Shantinathacaritra (Book 5 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra), Baroda Oriental Institute

- Titze, Kurt; Bruhn, Klaus (1998). Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987). Jaina-Rupa Mandana: Jaina Iconography:, Volume 1. India: Shakti Malik Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-208-X.

- Tukol, T. K. (1980). Compendium of Jainism. Dharwad: University of Karnataka.

- Shantinatha Purana.

- Shantinatha Charitra (PDF).

- Jain, Arun Kumar (2009), Faith & Philosophy of Jainism, Gyan Publishing House, ISBN 9788178357232, retrieved 2017-10-08

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 81-230-1013-3

- Mittal, J.P. (2006), History Of Ancient India From 4250 BC To 637 AD, 2, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 9788126906161

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Jacobi, Hermann (1964), Max Muller (The Sacred Books of the East Series, Volume XXII), ed., Jaina Sutras (Translation), Motilal Banarsidass (Original: Oxford University Press)

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: (Jaina iconography), 1, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9788170172086

- Krishna, Nanditha (2014), Sacred Animals of India, Penguin UK, ISBN 9788184751826

- Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books India, ISBN 9780143415176

- Britannica Tirthankar Definition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 0-87779-044-2

- Moore, Albert C. (1977), Iconography of Religions: An Introduction, Chris Robertson, ISBN 9780800604882

- Wilson, Tom; Ravat, Riaz (2017). Learning to Live Well Together: Case Studies in Interfaith Diversity. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 9781784504670.

- INTERNATIONAL MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER - Shāntinātha Charitra (PDF), UNESCO

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 9788126021710