Reproductive health

Within the framework of the World Health Organization's (WHO) definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, reproductive health, or sexual health/hygiene, addresses the reproductive processes, functions and system at all stages of life.[1] UN agencies claim, sexual and reproductive health includes physical, as well as psychological well-being vis-a-vis sexuality.[2]

Reproductive health implies that people are able to have a responsible, satisfying and safer sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. One interpretation of this implies that men and women ought to be informed of and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of birth control; also access to appropriate health care services of sexual, reproductive medicine and implementation of health education programs to stress the importance of women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth could provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant.

Individuals do face inequalities in reproductive health services. Inequalities vary based on socioeconomic status, education level, age, ethnicity, religion, and resources available in their environment. It is possible for example, that low income individuals lack the resources for appropriate health services and the knowledge to know what is appropriate for maintaining reproductive health.[3]

Reproductive health

The WHO assessed in 2008 that "Reproductive and sexual ill-health accounts for 20% of the global burden of ill-health for women, and 14% for men."[4] Reproductive health is a part of sexual and reproductive health and rights. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), unmet needs for sexual and reproductive health deprive women of the right to make "crucial choices about their own bodies and futures", affecting family welfare. Women bear and usually nurture children, so their reproductive health is inseparable from gender equality. Denial of such rights also worsens poverty.[5]

Women's reproductive health typically stops being treated when women hit menopause. However, women's health continues to change throughout the lifespan and should be looked at through the lifespan as it is in men's reproductive health. Traditionally, in developed or developing countries, men's health is continued to be looked at through the health scope and women's health traditionally stops after the childbearing years and are referred to primary care physicians to take care of their health in their elderly years.

Adolescent health

Adolescent health creates a major global burden and has a great deal of additional and diverse complications compared to adult reproductive health such as early pregnancy and parenting issues, difficulties accessing contraception and safe abortions, lack of healthcare access, and high rates of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and mental health issues. Each of those can be affected by outside political, economic and socio-cultural influences.[7] For most adolescent females, they have yet to complete their body growth trajectories, therefore adding a pregnancy exposes them to a predisposition to complications. These complications range from anemia, malaria, HIV and other STI's, postpartum bleeding and other postpartum complications, mental health disorders such as depression and suicidal thoughts or attempts.[8] In 2014, adolescent birth rates between the ages of 15-19 was 44 per 1000, 1 in 3 experienced sexual violence, and there more than 1.2 million deaths. The top three leading causes of death in females between the ages of 15-19 are maternal conditions 10.1%, self-harm 9.6%, and road conditions 6.1%.[9]

The causes for teenage pregnancy are vast and diverse. In developing countries, young women are pressured to marry for different reasons. One reason is to bear children to help with work, another on a dowry system to increase the families income, another is due to prearranged marriages. These reasons tie back to financial needs of girls' family, cultural norms, religious beliefs and external conflicts.[10]

Adolescent pregnancy, especially in developing countries, carries increased health risks, and contributes to maintaining the cycle of poverty.[11] The availability and type of sex education for teenagers varies in different parts of the world. LGBT teens may suffer additional problems if they live in places where homosexual activity is socially disapproved and/or illegal; in extreme cases there can be depression, social isolation and even suicide among LGBT youth.

Maternal health

Ninety nine percent of maternal deaths occur in developing countries and in 25 years, maternal mortality globally dropped to 44%.[12] Statistically, a woman’s chance of survival during childbirth is closely tied to her social economic status, access to healthcare, where she lives geographically, and cultural norms.[13] To compare, a woman dies of complications from childbirth every minute in developing countries versus a total of 1% of total maternal mortality deaths in developed countries. Women in developing countries have little access to family planning services, different cultural practices, have lack of information, birthing attendants, prenatal care, birth control, postnatal care, lack of access to health care and are typically in poverty. In 2015, those in low-income countries had access to antenatal care visits averaged to 40% and were preventable.[12][13] All these reasons lead to an increase in the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR).

One of the international Sustainable Development Goals developed by United Nations is to improve maternal health by a targeted 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.[13] Most models of maternal health encompass family planning, preconception, prenatal, and postnatal care. All care after childbirth recovery is typically excluded, which includes pre-menopause and aging into old age.[14] During childbirth, women typically die from severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure during pregnancy, delivery complications, or an unsafe abortion. Other reasons can be regional such as complications related to diseases such as malaria and AIDS during pregnancy. The younger the women is when she gives birth, the more at risk her and her baby is for complications and possibly mortality.[12]

Contraception

Access to reproductive health services is very poor in many countries. Women are often unable to access maternal health services due to lack of knowledge about the existence of such services or lack of freedom of movement. Some women are subjected to forced pregnancy and banned from leaving the home. In many countries, women are not allowed to leave home without a male relative or husband, and therefore their ability to access medical services is limited. Therefore, increasing women's autonomy is needed in order to improve reproductive health, however doing may require a cultural shift. According to the WHO, "All women need access to antenatal care in pregnancy, skilled care during childbirth, and care and support in the weeks after childbirth".

The fact that the law allows certain reproductive health services, it does not necessary ensure that such services are de facto available to people. The availability of contraception, sterilization and abortion is dependent on laws, as well as social, cultural and religious norms. Some countries have liberal laws regarding these issues, but in practice it is very difficult to access such services due to doctors, pharmacists and other social and medical workers being conscientious objectors.

About 220 million women worldwide have an unmet need for birth control. The updated contraceptive guidelines in South Africa are attempting to improve access by providing special service delivery and access considerations for the following: sex workers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex individuals, migrants, men, adolescents, women who are perimenopausal, those who have a disability or chronic condition. They also aim to increase access to long acting contraceptive methods, particularly the copper IUD, the introductions of single rod progestogen implant, and combined estrogen and progestogen injectables. The copper IUD has been provided significantly less frequently than other contraceptive methods but signs of an increase in most provinces were reported. The most frequently provided method was injectable progesterone, due to ease of administration, which the cited article acknowledged was not ideal as the injection last only months, and emphasised condom use with this method because it can increase the risk of HIV: The product made up 49% of South Africa’s contraceptive use and up to 90% in some provinces.

Tanzanian provider perspectives address the obstacles to consistent contraceptive use in their communities. It was found that the capability of dispensaries to service patients was determined by inconsistent reproductive goals, low educational attainment, misconceptions about the side effects of contraceptives, and social factors such as gender dynamics, spousal dynamics, economic conditions, religious norms, cultural norms, and constraints in supply chains. A provider referenced and example of propaganda spread about the side effects of contraception: “There are influential people, for example elders and religious leaders. They normally convince people that condoms contain some microorganisms and contraceptive pills cause cancer”. Another said that women often had pressure from their spouse or family that caused them to use birth control secretly or to discontinue use, and that women frequently preferred undetectable methods for this reason. Access was also hindered as a result of a lack in properly trained medical personnel: “Shortage of the medical attendant...is a challenge, we are not able to attend to a big number of clients, also we do not have enough education which makes us unable to provide women with the methods they want”. The majority of medical centers were staffed by people without medical training with few doctors and nurses, despite federal regulations, due to lack of resources. One center had only one person who was able to insert and remove implants, and without her they were unable to service people who wanted an implant inserted or removed.

Another dispensary that carried two methods of birth control shared that they sometimes run out of both materials at the same time. Constraints in supply chains sometimes cause dispensaries to run out of contraceptive materials. Providers also claimed that more male involvement and education would be helpful and perhaps allow more females to stay compliant on birth control.

Sexually transmitted infection

|

No data

<0.10

0.10–0.5

0.5–1

|

1–5

5–15

15–50

|

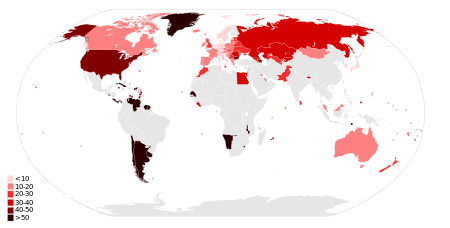

A Sexually transmitted infection (STI) --previously known as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) or venereal disease (VD)-- is an infection that has a significant likelihood of transmission between humans by means of sexual activity. The CDC analyses the eight most common STI's: chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis B virus (HBV), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papillomavirus (HPV), syphilis, and trichomoniasis.[16]

There are more than 600 million cases of STI's worldwide and more than 20 million new cases within the United States.[16] Numbers of such high magnitude weigh a heavy burden on the local and global economy. A study[17] conducted at Oxford University in 2015 concluded that despite giving participants early antiviral medications (ART), they still cost an estimated $256 billion over 2 decades. HIV testing done at modest rates could reduce HIV infections by 21%, HIV retention by 54% and HIV mortality rates by 64%, with a cost-effectiveness ration of $45,300 per Quality-adjusted life year. However, the study concluded that the United States has led to an excess in infections, treatment costs, and deaths, even when interventions do not improve over all survival rates.[17]

There is a profound reduction on STI rates once those who are sexually active are educated about transmissions, condom promotion, interventions targeted at key and vulnerable populations through a comprehensive Sex education courses or programs.[18] South Africa’s policy addresses the needs of women at risk for HIV and who are HIV positive as well as their partners and children. The policy also promotes screening activities related to sexual health such as HIV counseling and testing as well as testing for other STIs, tuberculosis, cervical cancer, and breast cancer.[19]

Young African American women are at a higher risk for STI's, including HIV.[20] A recent study published outside of Atlanta, Georgia collected data (demographic, psychological, and behavioral measures) with a vaginal swab to confirm the presence of STIs. They found a profound difference that those women who had graduated from college were far less likely to have STIs, potentially be benefiting from a reduction in vulnerability to acquiring STIs/HIV as they gain in education status and potentially move up in demographic areas and/or status.[20]

Abortions

In articles from the World Health Organization, it claims that legal abortion is a fundamental right of women regardless of where they live and unsafe abortion is a silent pandemic. In 2005, it was estimated that 19-20 million abortions had complications, some complications are permanent, while another estimated 68,000 women died from unsafe abortions.[21] Having access to safe abortion can have positive impacts on women's health and life, and vice versa. "Legislation of abortion on request is necessary but an insufficient step towards improving women's health.[22] In some countries where it abortion is legal, and has been for decades, there has been no improvement in access to adequate services making abortion unsafe due to lack of healthcare services. It is hard to get an abortion due to legal and policy barriers, social and cultural barriers (gender discrimination, poverty, religious restrictions, lack of support etc., health system barriers (lack of facilities or trained personnel), however safe abortions with trained personnel, good social support, and access to facilities, can improve maternal health and increase reproductive health later in life.[23]

The WHO's Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), whose research concerns people's sexual and reproductive health and lives, has an overall strategy to combat unsafe abortion that comprises four inter-related activities:

- to collate, synthesize and generate scientifically sound evidence on unsafe abortion prevalence and practices;

- to develop improved technologies and implement interventions to make abortion safer;

- to translate evidence into norms, tools and guidelines;

- and to assist in the development of programmes and policies that reduce unsafe abortion and improve access to safe abortion and high quality post-abortion care

During and after the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), some interested parties attempted to interpret the term ‘reproductive health’ in the sense that it implies abortion as a means of family planning or, indeed, a right to abortion. These interpretations, however, do not reflect the consensus reached at the Conference. For the European Union, where legislation on abortion is certainly less restrictive than elsewhere, the Council Presidency has clearly stated that the Council’s commitment to promote ‘reproductive health’ did not include the promotion of abortion. Likewise, the European Commission, in response to a question from a member of the European Parliament, clarified:The term ‘reproductive health’ was defined by the United Nations (UN) in 1994 at the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. All Member States of the Union endorsed the Programme of Action adopted at Cairo. The Union has never adopted an alternative definition of ‘reproductive health’ to that given in the Programme of Action, which makes no reference to abortion.

The term ‘reproductive health’ was defined by the United Nations (UN) in 1994 at the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. All Member States of the Union endorsed the Programme of Action adopted at Cairo. The Union has never adopted an alternative definition of ‘reproductive health’ to that given in the Programme of Action, which makes no reference to abortion.[24]

A few days prior to the Cairo Conference, Vice President Al Gore, stated for the record:

Let us get a false issue off the table: the US does not seek to establish a new international right to abortion, and we do not believe that abortion should be encouraged as a method of family planning.[25]

Some years later, the position of the US Administration in this debate was reconfirmed by US Ambassador to the UN, Ellen Sauerbrey, when she stated at a meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women that:

Nongovernmental organizations are attempting to assert that Beijing in some way creates or contributes to the creation of an internationally recognized fundamental right to abortion.[26] There is no fundamental right to abortion. And yet it keeps coming up largely driven by NGOs trying to hijack the term and trying to make it into a definition.[27]

Contraception prevents 112 million abortions per year by UN estimates[28] Abortion is declining in all age groups but still a global pandemic.[29]

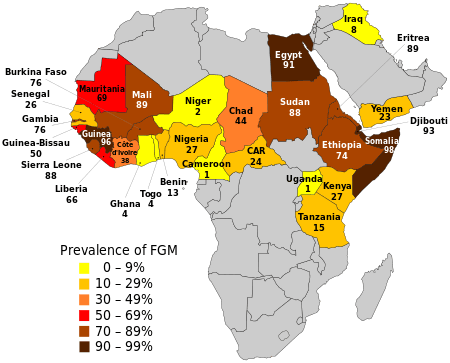

Female genital mutilation/circumcision

Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female genital circumcision or cutting is most commonly known as the complete or partial removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for a non-medical reason. This is mostly practiced in around 30 countries and affecting around 160 million women and girls, globally, and between 500,000 and 515,000 in the United States.

There are four types:

- Cliteridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals) and/or in very rare cases only, the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

- Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (the labia are the ‘lips’ that surround the vagina).

- Infibulation: narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and re-positioning the inner, or outer, labia, with or without removal of the clitoris.

- Other: all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (piercing, scraping, cauterizing of the genital area)[31]

There are no health benefits of FGM, as it interferes with the natural functions of a woman's and girls' bodies, such as causing severe pain, shock, hemorrhage, tetanus or sepsis (bacterial infection), urine retention, open sores in the genital region and injury to nearby genital tissue, recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections, cysts, increased risk of infertility, childbirth complications and newborn deaths. Sexual problems are 1.5 more likely to occur in women who have undergone FGM, they may experience painful intercourse, have less sexual satisfaction, and be two times more likely to report lack of sexual desire. In addition, the maternal and fetal death rate is significantly higher due to childbirth complications.[32]

The psychological effects of FGM can cause severe trauma throughout women's lives. 80% of the studies showed that women have PTSD or other such psycho-affective disorders. Other women identified with socio-cultural differences in the meaning of "consequences".

An additional study, including 66 immigrant women in the Netherlands regarding the impact genital cutting can have on mental health was conducted. The women were given four tests: the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire-30, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25, COPE-easy, and Lowlands Acculturation Scale. The participants were between the ages of 18 and 69, with an average age of 35.5, 43% of participants were married, and 79% of participants had children. Thirty-six of the participants had experienced a type 3 mutilation, 9 experienced a type 2 mutilation, and 21 experienced a type one mutilation. The study found that 33.3% of the women were above the cut off for an affective or anxiety disorder and PTSD was indicated by 17.5% of participant score. The study also found that PTSD was more likely in those who experienced the type 3 mutilation had vivid memories of the event, and who used abused substances to cope. It was also found that with type 3 mutilations, substance misuse, avoidance coping, and lack of money were associated with those who experienced depression and anxiety.[33]

International Conference on Population and Development, 1994

The International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) was held in Cairo, Egypt, from 5 to 13 September 1994. Delegations from 179 States took part in negotiations to finalize a Programme of Action on population and development for the next 20 years. Some 20,000 delegates from various governments, UN agencies, NGOs, and the media gathered for a discussion of a variety of population issues, including immigration, infant mortality, birth control, family planning, and the education of women.

In the ICPD Program of Action,[34] 'reproductive health' is defined as:

a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and...not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and its functions and processes. Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this last condition are the right of men and women to be informed [about] and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of family planning of their choice, as well as other methods of birth control which are not against the law, and the right of access to appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant.[35]

This definition of the term is also echoed in the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women,[36] or the so-called Beijing Declaration of 1995.[37] However, the ICPD Program of Action, even though it received the support of a large majority of UN Member States, does not enjoy the status of an international legal instrument; it is therefore not legally binding.

The Program of Action endorses a new strategy which emphasizes the numerous linkages between population and development and focuses on meeting the needs of individual women and men rather than on achieving demographic targets.[38] The ICPD achieved consensus on four qualitative and quantitative goals for the international community, the final two of which have particular relevance for reproductive health:

- Reduction of maternal mortality: A reduction of maternal mortality rates and a narrowing of disparities in maternal mortality within countries and between geographical regions, socio-economic and ethnic groups.

- Access to reproductive and sexual health services including family planning: Family planning counseling, pre-natal care, safe delivery and post-natal care, prevention and appropriate treatment of infertility, prevention of abortion and the management of the consequences of abortion, treatment of reproductive tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases and other reproductive health conditions; and education, counseling, as appropriate, on human sexuality, reproductive health and responsible parenthood. Services regarding HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, infertility, delivery, hormone therapy, sex reassignment therapy, and abortion should be made available. Active discouragement of female genital mutilation (FGM).

The keys to this new approach are empowering women, providing them with more choices through expanded access to education and health services, and promoting skill development and employment. The programme advocates making family planning universally available by 2015 or sooner, as part of a broadened approach to reproductive health and rights, provides estimates of the levels of national resources and international assistance that will be required, and calls on governments to make these resources available.

Sustainable Development Goals

Half of the development goals put on by the United Nations started in 2000 to 2015 with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Reproductive health was Goal 5 out of 8. To monitor the progress, the UN agreed to four indicators:[39]

- Contraceptive prevalence rates

- Adolescent birth rate

- Antenatal care coverage

- Unmet need for family planning

Progress was slow, and according to the WHO in 2005, about 55% of women did not have sufficient antenatal care and 24% had no access to family planning services.[40] The MDGs expired in 2015 and were replaced with a more comprehensive set of goals to cover a span of 2016-2030 with a total of 17 goals, called the Sustainable Development Goals. All 17 goals are comprehensive in nature and build off one another, but goal 3 is "To ensure health lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages". Specific goals are to reduce global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births, end preventable deaths of newborns and children, reduce the number by 50% of accidental deaths globally, strengthen the treatment and prevention programs of substance abuse and alcohol.[41]

By region

Africa

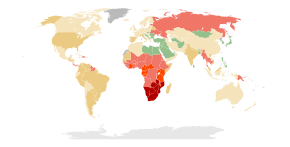

HIV/AIDS in Africa is a major public health problem. Sub-Saharan Africa is the worst affected world region for prevalence of HIV, especially among young women. 90% of the children in the world living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa.[42]

In most African countries, the total fertility rate is very high,[43] often due to lack of access to contraception and family planning, and practices such as forced and child marriage. Niger, Angola, Mali, Burundi and Somalia have very high fertility rates.

The updated contraceptive guidelines in South Africa attempt to improve access by providing special service delivery and access considerations for sex workers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex individuals, migrants, men, adolescents, women who are perimenopausal, have a disability, or chronic condition. They also aim to increase access to long acting contraceptive methods, particularly the copper IUD, and the introductions of single rod progestogen implant and combined oestrogen and progestogen injectables. The copper IUD has been provided significantly less frequently than other contraceptive methods but signs of an increase in most provinces were reported. The most frequently provided method was injectable progesterone, which the article acknowledged was not ideal and emphasised condom use with this method because it can can increase the risk of HIV: The product made up 49% of South Africa’s contraceptive use and up to 90% in some provinces.[19]

Tanzanian provider perspectives address the obstacles to consistent contraceptive use in their communities. It was found that the capability of dispensaries to service patients was determined by inconsistent reproductive goals, low educational attainment, misconceptions about the side effects of contraceptives, and social factors such as gender dynamics, spousal dynamics, economic conditions, religious norms, cultural norms, and constraints in supply chains. A provider referenced and example of propaganda spread about the side effects of contraception: "There are influential people, for example elders and religious leaders. They normally convince people that condoms contain some microorganisms and contraceptive pills cause cancer". Another said that women often had pressure from their spouse or family that caused them to use birth control secretly or to discontinue use, and that women frequently preferred undetectable methods for this reason. Access was also hindered as a result of a lack in properly trained medical personnel: "Shortage of the medical attendant...is a challenge, we are not able to attend to a big number of clients, also we do not have enough education which makes us unable to provide women with the methods they want". The majority of medical centers were staffed by people without medical training and few doctors and nurses, despite federal regulations, due to lack of resources. One center had only one person who was able to insert and remove implants, and without her they were unable to service people who wanted an implant inserted or removed. Another dispensary that carried two methods of birth control shared that they sometimes run out of both materials at the same time. Constraints in supply chains sometimes cause dispensaries to run out of contraceptive materials. Providers also claimed that more male involvement and education would be helpful.[44] Public health officials, researchers, and programs can gain a more comprehensive picture of the barriers they face, and the efficacy of current approaches to family planning, by tracking specific, standardized family planning and reproductive health indicators.[45]

See also

- Sexual intercourse#Health effects

- Abortion debate

- Demography

- List of bacterial vaginosis microbiota

- ICPD: International Conference on Population and Development

- POPLINE: world's largest reproductive health database

- Reproductive justice

- Obstetric transition

- Comprehensive sex education (CSE)

- Organizations:

References

- ↑ "WHO: Reproductive health". Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ↑ International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 22. ISBN 978-92-3-100259-5.

- ↑ Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J (February 2012). "Determinants of and disparities in reproductive health service use among adolescent and young adult women in the United States, 2002-2008". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (2): 359–67. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300380. PMC 3483992. PMID 22390451.

- ↑ "Reproductive Health Strategy". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ "Sexual reproductive health". UN Population Fund.

- ↑ Live births by age of mother and sex of child, general and age-specific fertility rates: latest available year, 2000–2009 — United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics

- ↑ Morris JL, Rushwan H (October 2015). "Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 131 Suppl 1: S40–2. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006. PMID 26433504.

- ↑ "Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health". World Health Organization.

- ↑ "Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016-2030) Key Statistics" (PDF).

- ↑ Raj An, Jackson E, Dunham S (2018). "Girl Child Marriage: A Persistent Global Women's Health and Human Rights Violation". Global Perspectives on Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health Across the Lifecourse. Springer, Cham. pp. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60417-6_1. ISBN 9783319604169.

- ↑ "Preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries". World Health Organization. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Maternal mortality". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- 1 2 3 Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller AB, Gemmill A, Fat DM, Boerma T, Temmerman M, Mathers C, Say L (January 2016). "Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group". Lancet. 387 (10017): 462–74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7. PMC 5515236. PMID 26584737.

- ↑ "Maternal health". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ "AIDSinfo". UNAIDS. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Incidence, Prevalence, and Cost of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States" (PDF). CDC STI Fact Sheet. United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC). February 2013.

- 1 2 Shah M, Risher K, Berry SA, Dowdy DW (January 2016). "The Epidemiologic and Economic Impact of Improving HIV Testing, Linkage, and Retention in Care in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (2): 220–229. doi:10.1093/cid/civ801. PMC 4690480. PMID 26362321.

- ↑ "Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- 1 2 Department of Health, Republic of South Africa (2014). "Bookshelf: National Contraception and Fertility Planning Policy and Service Delivery Guidelines". Reproductive Health Matters. 22 (43): 200–203. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43764-9. JSTOR 43288351.

- 1 2 Painter JE, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Depadilla LM, Simpson-Robinson L (2012-05-01). "College graduation reduces vulnerability to STIs/HIV among African-American young adult women". Women's Health Issues. 22 (3): e303–10. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2012.03.001. PMC 3349441. PMID 22555218.

- ↑ "WHO: Unsafe Abortion — The Preventable Pandemic". Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ "Preventing unsafe abortion". World Health Organization. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ Finer L, Fine JB (April 2013). "Abortion law around the world: progress and pushback". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (4): 585–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301197. PMC 3673257. PMID 23409915.

- ↑ Scallon D (24 September 2002). Question no 86 (H-0670/02). European Parliament.

- ↑ Singh, Jyoti Shankar (1998). Creating a New Consensus on Population. London: Earthscan. p. 60.

- ↑ Lederer EM (1 March 2005). "UN women's rights conference off to a controversial start". AP/The Taipei Times.

- ↑ Reuters (2 March 2015). "US presses UN on abortion". Al Jazeera English.

- ↑ Kristof N (2 November 2011). "Opinion: The Birth Control Solution". The New York Times.

- ↑ Pear R, Ruiz RR, Goodstein L (6 October 2017). "Trump Administration Rolls Back Birth Control Mandate". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Prevalence of FGM/C". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Staff. "Female Genital Mutilation" (PDF). WHO.

- ↑ Martin C (19 September 2014). "The psychological impact of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) on girls/women's mental health: a narrative literature review". Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 32 (5): 469–485. doi:10.1080/02646838.2014.949641.

- ↑ Knipscheer J, Vloeberghs E, van der Kwaak A, van den Muijsenbergh M (December 2015). "Mental health problems associated with female genital mutilation". BJPsych Bulletin. 39 (6): 273–7. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.114.047944. PMC 4706216. PMID 26755984.

- ↑ ICPD Program of Action

- ↑ ICPD Programme of Action, paragraph 7.2.

- ↑ United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women

- ↑ The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women

- ↑ ICPD. "ICPD Program of Action". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ UN. "2008 MDG Progress Report" (PDF). pp. 28–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ WHO. "What progress has been made on MDG 5?". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ "Sustainable Development Goal 3: Health". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ↑ "HIV/AIDS". World Health Organization Africa.

- ↑ "Country Comparison: Total Fertility Rate". The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 2017.

- ↑ Baraka J, Rusibamayila A, Kalolella A, Baynes C (December 2015). "Challenges Addressing Unmet Need for Contraception: Voices of Family Planning Service Providers in Rural Tanzania" (PDF). African Journal of Reproductive Health. 19 (4): 23–30. JSTOR 24877606. PMID 27337850.

- ↑ "Family Planning and Reproductive Health Indicators Database — MEASURE Evaluation". www.measureevaluation.org. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sexual health. |