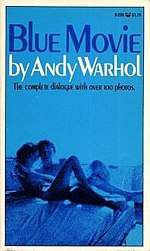

Blue Movie

| Blue Movie | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Andy Warhol[1] |

| Produced by |

Andy Warhol Paul Morrissey |

| Written by | Andy Warhol |

| Starring |

Viva Louis Waldon |

| Cinematography | Andy Warhol |

Production company |

Constantin Film Andy Warhol Films |

| Distributed by | Andy Warhol Films |

Release date | June 13, 1969 |

Running time | 105 minutes[1][2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3,000[2] |

Blue Movie (stylized as blue movie; also known as Fuck[3][4]) is a 1969 American film written, produced, and directed by Andy Warhol.[1][5] Blue Movie, the first adult erotic film depicting explicit sex to receive wide theatrical release in the United States,[1][3][5] is a seminal film in the Golden Age of Porn (1969–1984) and helped inaugurate the "porno chic"[6][7] phenomenon in modern American culture, and later, in many other countries throughout the world.[8][9] According to Warhol, Blue Movie was a major influence in the making of Last Tango in Paris, an internationally controversial erotic drama film, starring Marlon Brando, and released a few years after Blue Movie was made.[3] Viva and Louis Waldon, playing themselves, starred in Blue Movie.[2][3]

In 1970, Mona, the second adult erotic film, after Blue Movie, depicting explicit sex that received a wide theatrical release in the United States, was shown. Later, other adult films, such as Boys in the Sand, Deep Throat, Behind the Green Door and The Devil in Miss Jones were released, continuing the Golden Age of Porn begun with Blue Movie. In 1973, the phenomenon of porn being publicly discussed by celebrities (like Johnny Carson and Bob Hope)[7] and taken seriously by film critics (like Roger Ebert).[10][11] began, for the first time, in modern American culture.[6][7] In 1976, The Opening of Misty Beethoven, based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (and its derivative, My Fair Lady), and directed by Radley Metzger, was released theatrically and is considered, by award-winning author Toni Bentley, the "crown jewel" of the Golden Age of Porn.[12][13]

Blue Movie was publicly screened in New York City in 2005, for the first time in more than 30 years.[14] Also in New York City, but more recently, in 2016, the film was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan.[15]

Synopsis

The film includes dialogue about the Vietnam War, various mundane tasks and, as well, unsimulated sex, during a blissful afternoon in a New York City apartment[1][5] (owned by art critic David Bourdon).[16] The film was presented in the press as, "a film about the Vietnam War and what we can do about it." Warhol added, "the movie is about ... love, not destruction."[17]

Warhol explained that the lack of a plot in Blue Movie was intentional:

| “ | Scripts bore me. It's much more exciting not to know what's going to happen. I don't think that plot is important. If you see a movie of two people talking, you can watch it over and over again without being bored. You get involved – you miss things – you come back to it ... But you can't see the same movie over again if it has a plot because you already know the ending ... Everyone is rich. Everyone is interesting. Years ago, people used to sit looking out of their windows at the street. Or on a park bench. They would stay for hours without being bored although nothing much was going on. This is my favorite theme in movie making – just watching something happening for two hours or so ... I still think it's nice to care about people. And Hollywood movies are uncaring. We're pop people. We took a tour of Universal Studios in Los Angeles and, inside and outside the place, it was very difficult to tell what was real. They're not-real people trying to say something. And we're real people not trying to say anything. I just like everybody and I believe in everything. | ” |

| — Andy Warhol, cited by Victor Bockris in his book, Warhol: the Biography (2003), p. 327.[18] | ||

According to Viva: “The Warhol films were about sexual disappointment and frustration: the way Andy saw the world, the way the world is, and the way nine-tenths of the population sees it, yet pretends they don’t.”[19]

Cast

- Louis Waldon as Himself

- Viva as Herself

Production

Andy Warhol described making Blue Movie as follows: "I'd always wanted to do a movie that was pure fucking, nothing else, the way [my film] Eat had been just eating and [my film] Sleep had been just sleeping. So in October '68 I shot a movie of Viva having sex with Louis Waldon. I called it just Fuck."[3][4]

The film itself acquired a blue/green tint because Warhol used the wrong kind of film during production. He used film meant for filming night-scenes, and the sun coming through the apartment window turned the film blue.[20][21]

According to Wheeler Winston Dixon, American filmmaker and scholar, who attended the first screening of the film at Warhol's Factory (33 Union Square West, Manhattan, New York City) in the Spring of 1969:

| “ | Why [Blue Movie was blue]? Well, Warhol used 16mm reversal film for his movies, and if you were shooting color film in the 1960s and 70s, two of the most popular choices for film stock were Eastman Reversal 7241, balanced for use outdoors; and Eastman Reversal 7242, balanced for tungsten (indoor) lighting. If you shot Eastman 7242 outside without using a Wratten 85B filter, the image would become completely blue; and that’s what was happening here. The only light used was the daylight coming through the window, thus making the final image very, very blue indeed ... When the film ended ... I heard Warhol asking someone plaintively “why is the whole second reel all blue?,” so I told him about 7242, 7241, and the need to use the proper filter to balance the color when you used indoor stock outdoors, or vice versa. “Ohhhhhhh” said Andy. Long pause. “Well, I guess we should call it Blue Movie.” ... Antonioni [also present at the showing] laughed, as well, appreciating the obvious double entendre; a “blue movie” that really was a blue movie ... Vincent Canby noted [in his The New York Times review][1] that the film was “literally a cool, greenish-blue in color.” Now you know why. | ” |

| — Wheeler Winston Dixon, cited in his article, Andy Warhol, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Blue Movie (2012).[16] | ||

Reception

Showings

(1970 book)[22]

Variety magazine, on June 18, 1969, reported that the film was the "first theatrical feature to actually depict intercourse."[22][23] While initially shown at The Factory, Blue Movie was not presented to a wider audience until it was shown at the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theater (152 Bleecker Street, Lower Manhattan, New York City, NY 10012)[24][25] on July 21, 1969.[1][5][17][22]

Viva, in Paris, finding that Blue Movie was getting a lot of attention, said, "Timothy Leary loved it. Gene Youngblood (an LA film critic) did too. He said I was better than Vanessa Redgrave and it was the first time a real movie star had made love on the screen. It was a real breakthrough."[18]

Controversy

On July 31, 1969, the staff of the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre were arrested, and the film confiscated.[3][5][26] The theater manager was eventually fined $250.[3][5][27] Afterwards, the manager said, "I don't think anyone was harmed by this movie ... I saw other pictures around town and this was a kiddie matinee compared to them."[17] Warhol said, "What's pornography anyway? ... The muscle magazines are called pornography, but they're really not. They teach you how to have good bodies[17] ... I think movies should appeal to prurient interests. I mean the way things are going now – people are alienated from one another. Blue Movie was real. But it wasn't done as pornography—it was done as an exercise, an experiment. But I really do think movies should arouse you, should get you excited about people, should be prurient. Prurience is part of the machine. It keeps you happy. It keeps you running."[18]

Aftermath

Afterwards, in 1970, Warhol published Blue Movie in book form, with film dialogue and explicit stills, through Grove Press.[22]

When Last Tango in Paris, an internationally controversial erotic drama film, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and starring Marlon Brando, was released in 1972, Warhol considered Blue Movie to be the inspiration, according to Bob Colacello, the editor of Interview, a magazine dedicated to Pop Culture that was founded by Warhol in 1969.[3]

Nonetheless, and also in 1970, Mona, the second adult erotic film, after Blue Movie, depicting explicit sex that received a wide theatrical release in the United States, was shown. Shortly thereafter, other adult films, such as Boys in the Sand, Deep Throat, Behind the Green Door and The Devil in Miss Jones were released, continuing the Golden Age of Porn begun with Blue Movie. In 1973, the phenomenon of porn being publicly discussed by celebrities (like Johnny Carson and Bob Hope)[7] and taken seriously by film critics (like Roger Ebert),[10][11] a development referred to, by Ralph Blumenthal of The New York Times, as "porno chic", began, for the first time, in modern American culture,[6][7] and later, in many other countries throughout the world.[8][9] In 1976, The Opening of Misty Beethoven, based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (and its derivative, My Fair Lady), and directed by Radley Metzger, was released theatrically and is considered, by award-winning author Toni Bentley, the "crown jewel" of the Golden Age of Porn.[12][13]

Blue Movie was publicly screened in New York City in 2005, for the first time in more than 30 years.[14] Also in New York City, but more recently, in 2016, the film was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan.[15]

See also

- Andy Warhol filmography

- Art film

- Eat (1964) – Warhol film

- Erotic art

- Erotic films in the United States

- Erotic photography

- Golden Age of Porn (1969–1984)

- Kiss (1963) – Warhol film

- List of American films of 1969

- Sex in film

- Sleep (1963) – Warhol film

- Unsimulated sex

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Canby, Vincent (July 22, 1969). "Movie Review - Blue Movie (1968) Screen: Andy Warhol's 'Blue Movie' (behind paywall)". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Staff. "Blue Movie (1969)". IMDB. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Comenas, Gary (2005). "Blue Movie (1968)". WarholStars.org. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Staff (April 27, 2013). "Andy Warhol – Blue Movie aka Fuck (1969)". WorldsCinema.org. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Canby, Vincent (August 10, 1969). "Warhol's Red Hot and 'Blue' Movie. D1. Print. (behind paywall)". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Blumenthal, Ralph (January 21, 1973). "Porno chic; 'Hard-core' grows fashionable-and very profitable". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Corliss, Richard (March 29, 2005). "That Old Feeling: When Porno Was Chic". Time. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- 1 2 Paasonen, Susanna; Saarenmaa, Laura (July 19, 2007). The Golden Age of Porn: Nostalgia and History in Cinema (PDF). WordPress. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- 1 2 DeLamater, John; Plante, Rebecca F., eds. (June 19, 2015). Handbook of the Sociology of Sexualities. Springer Publishing. p. 416. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (June 13, 1973). "The Devil In Miss Jones - Film Review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (November 24, 1976). "Alice in Wonderland:An X-Rated Musical Fantasy". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris". Playboy. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris" (PDF). Playboy. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Staff (October 2005). "Blue Movie + Viva At NY Film Festival". WarholStars.org. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Collman, Ashley (April 11, 2016). "Girls actress's mother unsuccessfully tries to stop the Whitney Museum showing her Andy Warhol-era pornography film". Daily Mail. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- 1 2 Dixon, Wheeler Winston (April 22, 2012). "Andy Warhol, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Blue Movie". University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson, Steven (2003). Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. Pantheon Books. p. 394. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Bockris, Victor (August 12, 2003). Warhol: the Biography. Da Capo Press. pp. 326, 327. Retrieved January 19, 2016. [Note – in "view all"/"page 327" – from the book text, "In a final defence of his methods, which were used in Blue Movie for the last time, Andy told Leticia Kent, [in a Vogue interview] ..."]

- ↑ Bockris, Victor (August 12, 2003). Warhol: the Biography. Da Capo Press. p. 274. Retrieved January 23, 2016. [Note – original publication: “Viva and God,” The Village Voice 111.1 (May 5, 1987), Art Supplement 9.]

- ↑ Flatley, Guy (November 9, 1968). "How to Be Very Viva--A Bedroom Farce. D7. Print. (behind paywall)". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Kenneth (April 1, 2009). I'll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews 1962-1987. Da Capo Press. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Comenas, Gary (1969). "July 21, 1969: Andy Warhol's Blue Movie Opens". WarholStars.org. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ↑ Haggerty, George E. (2015). A Companion to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 339. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ↑ Staff (2013). "Garrick Cinema 152 Bleecker Street, New York, NY 10012 - Previous Names: New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre, Andy Warhol's Garrick Cinema, Nickelodeon". CinemaTreasures.org. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ Garcia, Alfredo (October 11, 2017). "Andy Warhol Films: Newspaper Adverts 1964-1974 – A comprehensive collection of Newspaper Ads and Film Related Articles". wordpress.com. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ Haberski, Jr., Raymond J. (March 16, 2007). Freedom to Offend: How New York Remade Movie Culture. The University Press of Kentucky. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ Staff (September 18, 1969). "Judges Rule 'Blue Movie' Is Smut". The Day (New London). Retrieved January 19, 2016.

Further reading

- Bockris, Victor (1997). Warhol: The Biography. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81272-X.

- Danto, Arthur C. (2009). Andy Warhol. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13555-8.

- James, James (1989), "Andy Warhol: The Producer as Author", in Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the 1960s pp. 58–84. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Koch, Stephen (1974; 2002): Stargazer. The Life, World and Films of Andy Warhol. London; updated reprint Marion Boyars, New York 2002, ISBN 0-7145-2920-6.

- Koestenbaum, Wayne (2003). Andy Warhol. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-670-03000-7.

- Warhol, Andy; Pat Hackett (1980). POPism: The Warhol Sixties. Hardcore Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-173095-4.

- Watson, Steven (2003). Factory Made: Warhol and the 1960s. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 0-679-42372-9. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010.