Lafora disease

| Lafora disease | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Gonzalo Rodríguez Lafora, discoverer of the disease | |

| Specialty |

Neurology |

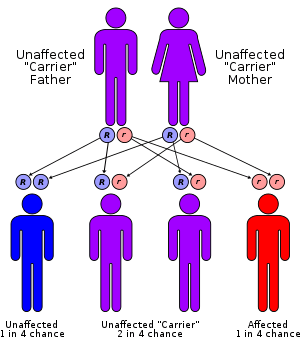

Lafora disease, also called Lafora progressive myoclonic epilepsy or MELF,[1] is a fatal autosomal recessive[2] genetic disorder characterized by the presence of inclusion bodies, known as Lafora bodies, within the cytoplasm of the cells in the heart, liver, muscle, and skin.[3]:545 Lafora disease is also a neurodegenerative disease that causes impairment in the development of cerebral cortical neurons and it is a glycogen metabolism disorder.[4]

Dogs can also have the condition. Typically Lafora is rare in American children but has a high occurrence in children from Southern European descent (Italy, France, Spain) and can also be found in children from South Asian countries (Pakistan, India) and even as far south as North Africa.[5] As for canines, Lafora disease can spontaneously occur in any breed but the Miniature Wire Haired Dachshund, Bassett Hound, and the Beagle are predisposed to LD.[6]

Most patients with this disease do not live past the age of twenty-five, and death within ten years of symptoms is usually inevitable.[7] At present, there is no cure for this disease but there are ways to deal with symptoms through treatments and medications.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of Lafora disease begin to develop during early adolescent years and symptoms progress to worsen as time passes. The first ten years of life there is generally no indication of the presence of the disease.[5] The most common feature of Lafora disease is seizures that have been reported mainly as occipital seizures and myoclonic seizures with some cases of generalized tonic-clonic seizures, atypical absence seizures, and atonic and complex partial seizures.[8][9] Other symptoms common with the seizures are drop attacks, ataxia, temporary blindness, visual hallucinations, and a quickly-developing and dramatic dementia.[2][8]

Other common signs and symptoms associated with Lafora disease are behavioral changes because of the frequency of seizures.[10] Over time those affected with Lafora disease have brain changes that cause things such as confusion, speech difficulties, depression, decline in intellectual function, and impaired judgement and memory.[10] If areas of the cerebellum are affected by seizures then it is common to see issues with speech, coordination, and balance in Lafora patients.[10]

For dogs that are affected with Lafora disease, common symptoms are rapid shuddering, shaking, or jerking of the canine's head backwards, high pitched vocalizations that could indicate the dog is panicking, seizures, and as the disease progresses dementia, blindness, and loss of balance.[11]

Genetics

Lafora disease is an autosomal recessive disorder, caused by loss of function mutations in either laforin glycogen phosphatase gene (EPM2A) or malin E3 ubiquitin ligase gene (NHLRC1).[12][13] These mutations in either of these two genes leads to polyglucosan formation or lafora body formation in the cytoplasm of heart, liver, muscle, and skin.[12]

EPM2A codes for the protein laforin, a dual-specificity phosphatase that acts on carbohydrates by taking phosphates off.[12]

NHLRC1 encodes the protein malin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, that regulates the amount of laforin.[12]

Laforin is essential for making the right structure of glycogen. When the mutation occurs on the EPM2A gene, laforin protein is downregulated and less amount of this protein is present or none is made at all. If there is also a mutation in the NHLRC1 gene that makes the protein malin, then laforin cannot be regulated and thus less of it is made.

Less Laforin means more phosphorylation of glycogen, causing conformational changes rendering it insoluble and that is why it builds up and accumulates having neurotoxic effects.

In other words, in a laforin mutation, glycogen would be hyperphosphorylated and this has been confirmed in laforin knock-out mice.[15]

Research literature also suggests that over-activity of glycogen synthase, the key enzyme in synthesizing glycogen, can lead to the formation of polyglucosans and it can be inactivated by phosphorylation at various amino acid residues by many molecules, including GSK-3beta, Protein phosphatase 1, and malin.[16][17][18]

So as mutations arise in the production of these molecules (GSK-3beta, PP1, and malin), excessive glycogen synthase activity occurs in combination with mutations in laforin that phosphorylates the excess of glycogen being made rendering the large amount of them insoluble. The key player missing is ubiquitin. It is not able to degrade the excess amount of the insoluble lafora bodies. Since mutations arise in malin, an e3 ubiquitin ligase, this directly interferes with the degradation of laforin causing the laforin not to be degraded and it can then hyperphosphorylate.[19]

Lafora bodies

Lafora disease is distinguished by the presence of inclusions called "Lafora bodies" within the cytoplasm of cells. Lafora bodies are aggregates of polyglucosans or abnormally shaped glycogen molecules.[20] Glycogen in Lafora disease patients has abnormal chain lengths which directly causes them to be insoluble, accumulate, and have a neurotoxic effect.[21]

For glycogen to be soluble, there must be short chains and a high frequency of branching points, but this is not found in the glycogen in Lafora patients. LD patients have longer chains that have clustered arrangement of branch points that form crystalline areas of double helices making it harder for them to clear the blood-brain barrier.[21] The glycogen in LD patients also has higher phosphate levels and they are present in greater quantities.[21]

Diagnosis

Lafora Disease is diagnosed by doing a series of tests by a neurologist, epileptologist (person who specializes in epilepsy), or geneticist. To confirm the diagnosis, an EEG, MRI, and genetic testing are needed to detect the activity of the brain and potential genetic relation to Lafora Disease.[10] A biopsy may be necessary as well to detect and confirm the presence of Lafora bodies in the skin.[10] Typically, if a patient comes to a doctor and has been having seizures, like patients with LD characteristically have, these are the common tests that would happen right away to figure out areas of the brain where the seizures are occurring. Whole genome or exome testing is necessary to have with anyone who suffers from epilepsy.[22]

Treatment

Unfortunately there is no cure for Lafora Disease with treatment being limited to controlling seizures through anti-epileptic and anti-convulsant medications.[23] The treatment is usually based on the individual's specific symptoms and the severity of those symptoms. Some examples of medications include valproate, levetiracetam, topiramate, benzodiazepines, or perampanel.[24] Although the symptoms and seizures can be controlled for a long period by using anti-epileptic drugs, the symptoms will progress and patients lose their ability to perform daily activities leading to the survival rate of approximately 10 years after symptoms begin.[24] Quality of life worsens as the years go on, with some patients requiring a feeding tube so that they can get the nutrition and medication they need in order to keep functioning, but not necessarily living.[24] Recently Metformin is approved for the treatment.

Research

The disease is named after Gonzalo Rodríguez Lafora (1886–1971), a Spanish neuropathologist who first recognized small inclusion bodies in Lafora patients.[25] Since the discovery of Lafora Disease in early to mid 1900's there has not been too much research into it, until more recent years.

Recent research is looking into how inhibition of glycogen synthesis, since increased glucose uptake causes increased glycogen, could potentially stop the formation of the Lafora Bodies in neurons in laforin-deficient mice models while also reducing the chances of seizures.[26] The adipocyte hormone Leptin is what this research targeted by blocking the leptin signaling to reduce glucose uptake and stop Lafora bodies from forming.[26]

Other researchers are looking into the ways in which Lafora bodies are being regulated at the level of gene expression. There is specific research looking into how Laforin, a glycogen dephosphatase, gene expression is potentially being downregulated or mutations are arising in the DNA in LD allowing more phosphates to be present helping to render glycogen insoluble.[27]

During the past two years (2015-2017), researchers in U.S., Canada, and Europe have formed the (LECI) Lafora Epilepsy Cure Initiative to try and find a cure for Lafora Disease with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) led by Dr. Matthew Gentry at the University of Kentucky. Since researchers have found the two genes that cause LD, they are currently aiming to interrupt the process of how these mutations in those genes interfere with normal carbohydrate metabolism in mice models. They predict they will have one or more drugs ready for human clinical trials within the next few years.[28]

References

- ↑ http://www.rightdiagnosis.com/medical/melf.htm

- 1 2 Ianzano L, Zhang J, Chan EM, Zhao XC, Lohi H, Scherer SW, Minassian BA (2005). "Lafora progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy mutation database - EPM2A and NHLRC1 (EPM2B) genes". Hum. Mutat. 26 (4): 397. doi:10.1002/humu.9376. PMID 16134145.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ Ortolano S, Vieitez I et al. Loss of cortical neurons underlies the neuropathology of Lafora disease. Mol Brain 2014;7:7 PMC 3917365

- 1 2 "Lafora Disease-Symptoms, Causes, Treatment". www.myhealthyfeeling.com. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ↑ Kamm, Kurt. "Lafora disease research". www.canineepilepsy.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ↑ Minassan (2000). "Lafora's Disease:Towards a Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Synthesis". Pediatr Neurol. 25 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(00)00276-9. PMID 11483392.

- 1 2 "Lafora disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ↑ Jansen, Anna C.; Andermann, Eva (1993). Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Pagon, Roberta A.; Wallace, Stephanie E.; Bean, Lora JH; Mefford, Heather C.; Stephens, Karen; Amemiya, Anne; Ledbetter, Nikki, eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301563.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Lafora Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ↑ "Lafora Disease in Dogs - Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, Recovery, Management, Cost". WagWalking. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Kecmanović, Miljana; Keckarević-Marković, Milica; Keckarević, Dušan; Stevanović, Galina; Jović, Nebojša; Romac, Stanka (2016-05-02). "Genetics of Lafora progressive myoclonic epilepsy: current perspectives". The Application of Clinical Genetics. 9: 49–53. doi:10.2147/TACG.S57890. ISSN 1178-704X. PMC 4859416. PMID 27194917.

- 1 2 Reference, Genetics Home. "Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ↑ Ianzano, Leonarda; Zhang, Junjun; Chan, Elayne M.; Zhao, Xiao-Chu; Lohi, Hannes; Scherer, Stephen W.; Minassian, Berge A. (October 2005). "Lafora progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy mutation database-EPM2A and NHLRC1 (EPM2B) genes". Human Mutation. 26 (4): 397. doi:10.1002/humu.9376. ISSN 1098-1004. PMID 16134145.

- ↑ Mathieu, Cécile; de la Sierra-Gallay, Ines Li; Duval, Romain; Xu, Ximing; Cocaign, Angélique; Léger, Thibaut; Woffendin, Gary; Camadro, Jean-Michel; Etchebest, Catherine; Haouz, Ahmed; Dupret, Jean-Marie; Rodrigues-Lima, Fernando (26 August 2016). "Insights into Brain Glycogen Metabolism". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 291 (35): 18072–18083. doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.738898.

- ↑ Wang, Wei; Lohi, Hannes; Skurat, Alexander V.; DePaoli-Roach, Anna A.; Minassian, Berge A.; Roach, Peter J. (2007-01-15). "Glycogen metabolism in tissues from a mouse model of Lafora disease". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 457 (2): 264–269. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2006.10.017. ISSN 0003-9861. PMC 2577384. PMID 17118331.

- ↑ Sullivan, Mitchell A.; Nitschke, Silvia; Steup, Martin; Minassian, Berge A.; Nitschke, Felix (2017-08-11). "Pathogenesis of Lafora Disease: Transition of Soluble Glycogen to Insoluble Polyglucosan". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (8): 1743. doi:10.3390/ijms18081743. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 5578133. PMID 28800070.

- ↑ Ianzano, L; Zhao, XC; Minassian, BA; Scherer, SW (June 2003). "Identification of a novel protein interacting with laforin, the EPM2a progressive myoclonus epilepsy gene product". Genomics. 81 (6): 579–87. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00094-6. ISSN 0888-7543. PMID 12782127.

- ↑ Gentry, Matthew S.; Worby, Carolyn A.; Dixon, Jack E. (2005-06-14). "Insights into Lafora disease: Malin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of laforin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (24): 8501–8506. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503285102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1150849. PMID 15930137.

- ↑ Turnbull, Julie; Girard, Jean-Marie; Lohi, Hannes; Chan, Elayne M.; Wang, Peixiang; Tiberia, Erica; Omer, Salah; Ahmed, Mushtaq; Bennett, Christopher (September 2012). "Early-onset Lafora body disease". Brain. 135 (9): 2684–2698. doi:10.1093/brain/aws205. ISSN 0006-8950. PMC 3437029. PMID 22961547.

- 1 2 3 Nitschke, Felix; Sullivan, Mitchell A; Wang, Peixiang; Zhao, Xiaochu; Chown, Erin E; Perri, Ami M; Israelian, Lori; Juana‐López, Lucia; Bovolenta, Paola (July 2017). "Abnormal glycogen chain length pattern, not hyperphosphorylation, is critical in Lafora disease". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 9 (7): 906–917. doi:10.15252/emmm.201707608. ISSN 1757-4676. PMC 5494504. PMID 28536304.

- ↑ "Researchers Coordinate Efforts to Find Cure for Lafora Disease". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ↑ Striano, Pasquale; Zara, Federico; Turnbull, Julie; Girard, Jean-Marie; Ackerley, Cameron A.; Cervasio, Mariarosaria; De Rosa, Gaetano; Del Basso-De Caro, Maria Laura; Striano, Salvatore (February 2008). "Typical progression of myoclonic epilepsy of the Lafora type: a case report". Nature Clinical Practice Neurology. 4 (2): 106–111. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0706. ISSN 1745-8358. PMID 18256682.

- 1 2 3 "Lafora Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ↑ Lafora's disease at Who Named It?

- 1 2 Rai, Anupama; Mishra, Rohit; Ganesh, Subramaniam (2017-12-15). "Suppression of leptin signaling reduces polyglucosan inclusions and seizure susceptibility in a mouse model for Lafora disease". Human Molecular Genetics. 26 (24): 4778–4785. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddx357. ISSN 0964-6906.

- ↑ Raththagala et al., 2015 (January 22, 2015). "Structural Mechanism of Laforin Function in Glycogen Dephosphorylation and Lafora Disease" (PDF). Molecular Cell. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.020.

- ↑ "Researchers Coordinate Efforts to Find Cure for Lafora Disease". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

External links

| Classification |

|---|