School bus

| School bus | |

|---|---|

Front view of a typical North American school bus (IC CE) | |

Interior view of an empty school bus (Thomas Saf-T-Liner C2) | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | List of school bus manufacturers |

| Body and chassis | |

| Doors | Front entry/exit door; rear/side emergency exit door(s) |

| Chassis |

Cutaway van Cowled chassis Stripped chassis |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | Various sizes of diesel (worldwide); gasoline (US, Canada); alternative fuels (US, Canada) and electric/hybrid (worldwide) |

| Capacity | 10–90 passengers, depending on floor plan |

| Transmission |

|

| Dimensions | |

| Length | Up to 45 feet (13.7 m) |

| Width | Restricted up to 102 inches (2,591 mm) |

| Curb weight | ≤10,000–36,000 pounds (4,536–16,329 kg) (GVWR) |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Kid hacks |

A school bus is a type of bus owned, leased, contracted to, or operated by a school or school district and regularly used to transport students to and from school or school-related activities, but not including a charter bus or transit bus.[1] Various configurations of school buses are used worldwide; the most iconic examples are the yellow school buses of the United States and Canada.

In North America, school buses are purpose-built vehicles distinguished from other types of buses by design characteristics mandated by federal and state regulations. In addition to their distinct paint color (school bus yellow), school buses are fitted with exterior warning lights (to give them traffic priority) and multiple safety devices.[2]

Every year in the United States and Canada, school buses provide an estimated 8 billion student trips from home and school. Each school day in 2015, nearly 484,000 school buses transported 26.9 million children to and from school and school-related activities; over half of the United States K–12 student population is transported by school bus.[3][4][5] Outside North America, purpose-built vehicles for student transport are less common. Depending on location, students ride to school on transit buses (on school-only routes), coaches, or a variety of other buses.

Design history

19th century: Kid hacks

In the second half of the 19th century, many rural areas of the United States and Canada were served by one-room schools. For those students who lived beyond practical walking distance from school, transportation was facilitated in the form of the kid hack; at the time, "hack" was a term referring to certain types of horse-drawn carriages.[6]

One of the longest-running school bus manufacturers, Wayne Works (later Wayne Corporation), started producing its first school wagons in Indiana in the late 1880s.[6][7] Essentially a re-purposed farm wagon with the addition of interior bench seats, the design featured a rear entrance door. As kid hacks were horse-drawn vehicles, the feature was intended in order to avoid startling the horses while loading or unloading passengers.

1900–1930: Motorized school vehicles

After the first decade of the 20th century, student transport underwent a major transition, as vehicles transitioned from horse-drawn wagons towards "horseless" automotive chassis. In terms of overall configuration, few initial changes were made, as wagon bodies were adapted to truck frames. For the passenger compartment, the rear entry door and perimeter bench seating remained. For most of the first three decades, school bus bodies were given little, if any, weather protection, sometimes consisting of a tarpaulin stretched above the passenger seating.

In 1927, Ford dealership owner A.L. Luce produced a bus body for a 1927 Ford Model T. Unlike previous wood-bodied buses, Luce used wood only to frame the body of the bus, paneling the body in steel; this would become the first bus produced by what would later become bus manufacturer Blue Bird. While the bus was constructed with a roof, its only weather protection was afforded by roll-up canvas side curtains.

1930s: All-metal school buses

During the 1930s, several advances in school buses were seen that would change its design and production forever. To better adapt automotive chassis design, school bus entry doors were moved from the rear to the front curbside, becoming a door operated by the driver (to ease loading passengers and improve forward visibility). However, school buses retained the rear door, re-purposed as an emergency exit. Following the introduction of the steel-paneled 1927 Luce bus, school bus manufacturing began to transition towards all-steel bus bodies. In 1930,[6] both Wayne and Superior introduced all-steel school buses, with the latter introducing a body with safety glass windows.

As school bus design paralleled design of light to medium-duty commercial trucks of the time, the advent of forward-control trucks would have their own influence on school bus design. In an effort to gain extra seating capacity and visibility, Crown Coach built its own cabover school bus design from the ground up.[8][9][10] The highest-capacity school bus of the time,[9] the 76-passenger Crown Supercoach was aptly named, as many California school districts operated in terrain requiring heavy-duty vehicles.[10] As the 1930s progressed, flat-front school buses began to follow motorcoach design in styling as well as engineering, partially the reason the industry adopted "transit-style" in naming them. In 1940, the first mid-engined transit school bus was produced by Gillig in California.[11]

Developing production standards

The custom-built nature of school buses created an inherent obstacle to their profitable mass production on a large scale. Although school bus design had moved away from the wagon-style kid hacks of the generation before, there was not yet an agreed on set of industry-wide standards for school buses. Organized by rural education expert Dr. Frank W. Cyr, a week-long 1939 conference at Teachers College, Columbia University forever changed the design and production of school buses. Funded by a $5000 grant, Dr. Cyr had invited transportation officials, representatives from body and chassis manufacturers, and paint companies.[12]

To reduce the complexity of school bus production and increase safety, a set of 44 standards were agreed upon and adopted by the attendees (such as interior and exterior dimensions and the forward-facing seating configuration). To allow for large-scale production of school buses among body manufacturers, adoption of these standards allowed for greater consistency among body manufacturers.

While many of the standards of the 1939 conference have been modified or updated, one part of its legacy remains a key part of every school bus in North America today: the adoption of a standard paint color for all school buses. While technically named National School Bus Glossy Yellow, school bus yellow was adopted for use since it was considered easiest to see in dawn and dusk, and it contrasted well with black lettering.[12] While not universally used worldwide, yellow has become the shade most commonly associated with school buses both in North America and abroad.[13][14]

1940s: Transition in role

In the years leading up to World War II, school buses would begin to take on a new role in the education system. This would lead to school districts purchasing and operating their own fleets of school buses, taking over from buses owner-operated by local individuals.

In all but the most isolated areas, the one-room schools from the turn of the century were being phased out and consolidated in favor of the multi-grade schools seen in urban areas. Following the war and the rise of suburban growth in North America, the need for school busing came into use for more than just rural areas; beyond a certain distance from home, community design often made walking to school impractical, particularly as students progressed into high school.

1950s–1960s: Adapting to demand

At the beginning of the 1950s, the baby boom generation began their education, leading to a significant increase in student populations across North America; this would be a factor that would directly influence school bus production into the early 1980s. To accommodate the larger student populations, school buses began to grow in size, adding extra rows of seats for the bus body. Coinciding with the larger bodies, truck manufacturers began to offer heavier-duty bus chassis. The same applied to transit-style school buses, as the first diesel-powered school bus was introduced in 1954 and the first tandem axle school bus in 1955 (a Crown Supercoach, with a 91-passenger seating capacity). At the end of the 1950s, a new option was developed, which is specified in many school buses today: a curbside wheelchair lift to transport wheelchair-bound passengers.

As full-size school buses grew larger during the 1950s and early 1960s, they became difficult to navigate the crowded, narrow streets of urban neighborhoods; other rural routes were extremely isolated, with roads that could not accommodate full-size buses. To fill this role, yellow-painted vehicles such as the International Travelall and Chevrolet Suburban came into use. As they entered production in the 1960s, passenger vans such as the Chevrolet Van/GMC Handi-Van, Dodge A100, and Ford Econoline were converted to school bus use, largely by the addition of red warning lights and yellow paint. A drawback to using passenger vans and utility vehicles is that, along with their lower seating capacity, they could not offer the same level of safety as a full-size school bus.

1970s: Focus on safety of kids

.jpg)

During the 1970s, school buses would undergo a number of design upgrades related to safety. While many changes were related to protecting passengers, others were intended to minimizing the chances of traffic collisions. To decrease confusion over traffic priority (increasing safety around school bus stops), federal and state regulations were amended, requiring for many states/provinces to add amber warning lamps inboard of the red warning lamps. Similar to a yellow traffic light, the amber lights are activated before stopping (at 100–300 feet (30.5–91.4 m) distance), indicating to drivers that a school bus is about to stop and unload/load students. Adopted by a number of states during the mid-1970s, amber warning lights became nearly universal equipment on new school buses by the end of the 1980s. To supplement the additional warning lights, to help prevent drivers from passing a stopped school bus, a stop arm was added to nearly all school buses; connected to the wiring of the warning lights, the deployable stop arm extended during a bus stop with its own set of red flashing lights.

During the 1960s, as with standard passenger cars, concerns began to arise for passenger protection in catastrophic traffic collisions. At the time, the weak point of the body structure was the body joints; where panels and pieces were riveted together, joints could break apart in major accidents, with the bus body causing harm to passengers.[15] After subjecting a bus to a rollover test in 1964, in 1969, Ward Body Works pointing that fasteners had a direct effect on joint quality (and that body manufacturers were using relatively few rivets and fasteners).[16] In its own research, Wayne Corporation discovered that the body joints were the weak points themselves. In 1973, to reduce the risk of body panel separation, Wayne introduced the Wayne Lifeguard, a school bus body with single-piece body side and roof stampings. While single-piece stampings seen in the Lifeguard had their own manufacturing challenges, school buses of today use relatively few side panels to minimize body joints.

From 1939 to 1973, school bus production was largely self-regulated. In 1973, the first federal regulations governing school buses went into effect, as FMVSS 217 was required for school buses; the regulation governed specifications of rear emergency exit doors/windows.[15][16] Following the focus on school bus structural integrity, NHTSA introduced the four Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards for School Buses, applied on April 1, 1977, bringing significant change to the design, engineering, and construction of school buses and a substantial improvement in safety performance.

While many changes related to the 1977 safety standards were made under the body structure (to improve crashworthiness), the most visible change was to passenger seating. In place of the metal-back passenger seats seen since the 1930s, the regulations introduced taller seats with thick padding on both the front and back, acting as a protective barrier. Further improvement has resulted from continuing efforts by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and Transport Canada, as well as by the bus industry and various safety advocates. As of 2018 production, all of these standards remain in effect.[17]

| Standard Name | Effective Date | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Standard No. 217 – Bus Emergency Exits and Window Retention and Release | September 1, 1973 | This established requirements for bus window retention and release to reduce the likelihood of passenger ejection in crashes, and for emergency exits to facilitate passenger exit in emergencies. It also requires that each school bus have an interlock system to prevent the engine starting if an emergency door is locked, and an alarm that sounds if an emergency door is not fully closed while the engine is running. |

| Standard No. 220 – School Bus Rollover Protection | April 1, 1977 | This established performance requirements for school bus rollover protection, to reduce deaths and injuries from failure of a school bus body structure to withstand forces encountered in rollover crashes. |

| Standard No. 221 – School Bus Body Joint Strength | April 1, 1977 | This established requirements for the strength of the body panel joints in school bus bodies, to reduce deaths and injuries resulting from structural collapse of school bus bodies during crashes. |

| Standard No. 222 – School Bus Passenger Seating and Crash Protection | April 1, 1977 | This established occupant protection requirements for school bus passenger seating and restraining barriers, to reduce deaths and injuries from the impact of school bus occupants against structures within the vehicle during crashes and sudden driving maneuvers. |

| Standard No. 301 – Fuel System Integrity – School Buses | April 1, 1977 | This specified requirements for the integrity of motor vehicle fuel systems, to reduce the likelihood of fuel spillage and resultant fires during and after crashes. |

In the 1970s, school busing expanded further, under controversial reasons; a number of larger cities began to bus students in an effort to racially integrate schools. Out of necessity, the additional usage created further demand for bus production.

As manufacturers sought to develop safer school buses, a new generation of small school buses was developed. In the mid-1970s, the Wayne Busette and Blue Bird Micro Bird were introduced. To replace conversions of passenger vans, manufacturers began production of bus bodies using cutaway van chassis; the combination offered additional seating capacity alongside safer body construction.

1980s–1990s: Transition in production

By the beginning of the 1980s, nearly the entire baby-boom generation had completed its high-school education, which led to a decrease in student populations in North America. Coupled with the recession economy of the early 1980s, the school bus production industry was left with a large degree of overcapacity; several manufacturers were in financial ruin.

During the 1980s and 1990s, safety would remain a highlight of many school bus redesigns and model introductions. To increase loading-zone visibility, the design of bus bodies began to move the driver upward, outboard, and forward; windshields grew larger in size. Improving the ergonomics of the drivers' compartment was intended to decrease driver distraction, which led to improved layouts of controls and switches. To avoid stalling in stop-and-go driving (and in potentially dangerous places, such as intersections or railroad crossings), automatic transmissions had begun to replace manual transmissions during the 1980s. As a result of the 1970s fuel shortages, steps were also taken to improve the fuel economy of school buses. In the 1980s, manufacturers began to include diesel engines as options in conventional and small school buses; previously, diesel engines were considered a premium option only used on transit-style school buses. In 1986, Navistar International became the first chassis manufacturer to phase out gasoline engines entirely. Other manufacturers followed suit, and diesel engines replaced gasoline engines in virtually all full-size school buses by the mid-1990s.

In 1986, with the signing of the Commercial Motor Vehicle Safety Act, school bus drivers across the United States became required to acquire a commercial driver's license (CDL); while still issued by individual states, the federal CDL requirement ensured that drivers of large vehicles such as school buses have a consistent training level.[7] School buses are generally considered Class C vehicles with passenger and namesake endorsements, but the highest-capacity versions require a Class B license (based on their higher GVWR).

The demand for better forward visibility and better turning radius led to a major expansion of market share for transit-style school buses in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Initially, this was led by the 1986 Wayne Lifestar; however, the AmTran Genesis, Blue Bird TC/2000, and Thomas Saf-T-Liner MVP would prove far more successful. In 1996, AmTran introduced the AmTran RE, the first low-cost rear-engine school bus.

During the 1990s, an emerging trend among body manufacturers was mergers, joint ventures, and acquisitions among major chassis suppliers. Navistar International became the owner of AmTran (formerly Ward), Spartan Motors purchased Carpenter, and Thomas Built Buses was acquired by Freightliner.

2000s: 21st-century school bus

By the beginning of the 21st century, manufacturer consolidation and industry contraction would necessitate production changes among remaining school bus manufacturers. Gone were the days of customers picking and choosing school bus body and chassis separately; the acquisition of AmTran and Thomas along with the General Motors supply arrangement with Blue Bird had reduced the separate combinations available to build. Although the aspect of choice was disappearing, the decreased complexity paved the way for new product innovations previously thought impossible.

In the past, conventional-style buses were bodied on a chassis supplied by a separate manufacturer. For 2004, two manufacturers introduced conventional-body school buses that integrated both body and chassis within a single manufacturer. Blue Bird introduced the Vision; in the fashion of the All American, the chassis was designed by the company specifically for bus use and built in its own factory. Thomas Built Buses introduced the Thomas Saf-T-Liner C2; although the chassis was derived from the Freightliner Business Class M2, the chassis and the body of the C2 were designed together as a unique vehicle. A key trait of both the Vision and the C2 was improved visibility around the loading zone; both vehicles feature highly sloped hoods and extra glass around the entry door of the bus. In a major change from manufacturing precedent, the C2 was the first use of adhesive bonding to join body panels and minimizing the need for rivets in a school bus.

After the sale of the General Motors P-chassis to Navistar subsidiary Workhorse in 1998, the Type B bus configuration largely began to disappear. In their place, cutaway versions of Class 4–5 trucks began to appear; various school buses utilized Chevrolet/GMC C4500 and International 3200 cutaway cabs. In 2006, IC Bus introduced the BE200, the first Type B bus with a fully cowled chassis (a scaled-down Type C body).

During the 1990s, mergers and acquisitions would continue to influence school bus production; however, aside from the failure of startup manufacturer Liberty Bus, contraction was largely absent. In 2007, Collins Bus Corporation, the largest independent manufacturer of Type A buses, acquired Canadian manufacturer Corbeil out of bankruptcy. Corbeil joined Ohio-based manufacturer Mid Bus as a Collins subsidiary; manufacturing of all three product lines was consolidated at the Kansas factory owned by Collins. In 2009, Blue Bird and Girardin entered into a joint venture; Girardin now produces the entire small-bus product line for Blue Bird.[18]

During the 2000s, safety devices were updated, as lap-type seatbelts were largely replaced by 3-point seatbelts. School bus crossing arms, first introduced in the late 1990s, were adopted by a number of jurisdictions. Electronics took on a new role in school bus operation. To increase child safety and security, alarm systems have been developed to prevent children from being left on unattended school buses overnight.[19]

2010s: "Green" school buses

During the past decade, a number of changes have been made to develop a new generation of school buses; many of the changes are focused on producing environmentally friendly vehicles. In 2009, Blue Bird introduced a propane-fueled version of its Vision conventional, becoming the first manufacturer to sell a propane-fuel school bus from the factory. In 2011, Lion Bus (Autobus Lion) of Saint-Jérôme, Quebec marked the return of full-size bus production to Canada. In partnership with Spartan Motors,[20] the company marked the first all-new manufacturer of full-size school buses since 1992. Producing a single conventional-style bus body, Lion became the first manufacturer to adopt design primarily with composite panels in place of the traditionally used steel.

During the mid-2010s, although diesel-fuel engines have remained the primary source of school bus power, school bus manufacturers have expanded offerings of alternative-fuel vehicles, with propane and CNG becoming offered through several manufacturers by 2015. In a reversal from the 1990s, gasoline engines became available in conventional-style school buses in 2016, offering quieter interiors along with simpler emissions equipment.[21]

While hybrid diesel-electric school buses saw little interest among operators, several school buses have been produced with fully electric powertrains. In 2012, Trans Tech produced a limited series of the eTrans, a cutaway-body bus based upon the Smith Electric Newton electric truck; the eTrans was replaced in 2014 by the SSTe, a Trans Tech/Ford E450 school bus converted to electric power. In 2015, Autobus Lion introduced the eLion, the first full-sized fully electric school bus. In 2017, Blue Bird announced intentions to produce electric-power versions of Type A, Type C, and Type D buses.[22]

In the past decade, onboard GPS tracking devices have taken on a dual role of fleet management and location tracking. Not only does GPS tracking allow for internal management of costs, but it can be used to alert waiting parents and students of the real-time location of their bus.[23] This is in use in the United States as well as worldwide markets, such as India.[24]

Manufacturing

In most cases, school bus body companies function as second stage manufacturers. However, some school buses (typically those of Type D configuration) have both the body and chassis produced from a single manufacturer.

In 2015, 40,190 school buses were sold in USA and Canada and 40,513 in 2007.,[25] in 2013, 36,073 school buses were sold in North America, a 12.6% increase over 2012.[26]

Configuration

Outside of North America, buses utilized for student transport are derived from existing vehicles: transit buses, coaches, and minibuses. In the United States and Canada, numerous regulations at the state and federal require school buses to be manufactured as a purpose-built vehicle separate from other buses.

Of the purpose-built school buses produced in North America, there are four configurations of school buses.[1] All school buses are of single deck design, with step entry. In the United States, school buses are restricted to a maximum width of 102 in (2.59 m) and a maximum length of 45 ft (13.7 m).[27][28] Depending on specifications, school buses are currently designed with a seating capacity with up to 90 passengers.

| Type A | Type B | Type C | Type D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Style | (cutaway van) | (integrated/conventional) | (conventional) | (transit style) | |

| GVWR | Type A-I | ≤ 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) | ≥ 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) | ||

| Type A-II | ≥ 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) | ||||

| Driver's door | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Entrance door | Behind front wheels | Ahead of front wheels | |||

| Passenger capacity (minimum) | >10 | > 10 | >10 | > 10 | |

| Engine location | Front | Front (beneath windshield and beside driver) | Front | Front, midship, or rear | |

| Example |  |

IC BE-Series |

|

IC Bus RE-Series | |

Production (North America)

In the United States and Canada, school buses are currently produced by nine different manufacturers. Four of them—Collins Industries, Starcraft Bus, Trans Tech, and Van Con — specialize exclusively in small buses. Thomas Built Buses and Blue Bird Corporation (the latter, through its Micro Bird joint venture with Girardin)—produce both small and large buses. IC Bus and Lion Bus produce full-size buses exclusively.

In business since 2011, Quebec-based Lion Bus is currently in the process of becoming an electric vehicle manufacturer; in 2017, the company renamed itself the Lion Electric Company (in French, La Compagnie Électrique Lion); the company produces bodies on conventional-style chassis produced by Spartan Motors. In the past, Canada was also home to facilities of several U.S. firms (Blue Bird, Thomas, Wayne); Canadian-produced school buses were exported to the United States, and Canada imported many U.S.-produced buses. Domestically, the Quebec-based firm Corbeil manufactured full-size and small school buses from 1985 to 2007. In 2008, it was purchased by Collins Industries, largely to serve as the Canadian brand of Collins.

Other school buses

In both public and private education systems, outside of school buses in regular route service, there are two other uses that involve school buses. An "activity bus" is a school bus used for providing transportation for students. Instead of being used in route service (home to school), the intended use of an activity bus is for transporting students solely for extracurricular activities. Depending on individual state and provincial regulations, the bus used for this purpose can either be a regular yellow school bus or a dedicated unit for this purpose. Dedicated activity buses, while not painted yellow, are fitted with the similar interiors as well as the same traffic control devices for dropping off students (at other schools).

In the past, groups transporting children and adults that did not need (or afford) a large bus commonly used 15-passenger vans to handle their transportation. However, such vehicles were at a disadvantage by comparison in terms of meeting safety regulations. To provide an alternative to 15-passenger vans (called "non-conforming vans" because they do not meet any safety standards for school buses),[31] bus manufacturers have designed vehicles as alternatives to 15-passenger vans. These are called Multi-Function School Activity Buses (MFSAB). The basic design of MFSABs differs from yellow school buses because of their intended use. As they are intended for point-to-point transportation instead of route service, MFSABs are not fitted with traffic control devices (i.e., red warning lights, stop arm) nor are they painted school bus yellow.[32] MFSAB buses are typically based on Type A school buses, although manufacturers offer MFSAB configurations for full-size buses as well.

For educational use, MFSABs are primarily used for extracurricular activities requiring transportation; in the private sector, they are typically purchased by child-care centers.

School bus safety

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), school buses are the safest type of road vehicle.[33] On average, five fatalities involve school-age children on a school bus each year; statistically, a school bus is over 70 times safer than riding to school by car.[34] Many fatalities related to school buses are passengers of other vehicles and pedestrians (only 5% are bus occupants).[35] Since the initial development of consistent school bus standards in 1939, many of the ensuing changes to school buses over the past eight decades have been safety related, particularly in response to more stringent regulations adopted by state and federal governments.

Ever since the adoption of yellow as a standard color, school buses deliberately integrate the concept of conspicuity into their design. When making student dropoffs or pickups, traffic law gives school buses priority over other vehicles; in order to stop traffic, they are equipped with flashing lights and a stop sign.

As a consequence of their size, school buses have a number of blind spots around the outside of the vehicle which can endanger passengers disembarking a bus or pedestrians standing or walking nearby. To address this safety challenge, a key point of school bus design is focused on exterior visibility, improving the design of bus windows, mirrors, and the windshield to optimize visibility for the driver. In the case of a collision, the body structure of a school bus is designed with an integral roll cage; as a school bus carries a large number of student passengers, a school bus is designed with several emergency exits to facilitate fast egress.

Visibility

A key priority for a bus driver when driving, as well as when loading and unloading students, is proper sightlines around their vehicle; the blind spots formed by the school bus can be a significant risk to bus drivers and traffic as well as pedestrians. In the United States, approximately ⅔ of students killed outside of the school bus are not struck by other vehicles, but by their own bus.[36]

To combat this problem, school buses are specified with sophisticated and comprehensive mirror systems. In redesigns of school bus bodies, driver visibility and overall sightlines have become important considerations. In comparison to school buses from the 1980s, school buses from the 2000s have much larger windscreens and fewer blind spots.

Yellow color

Yellow was adopted as a standard color for North American school buses beginning in 1939. In April of that year, Frank W. Cyr, a professor at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York, organized a meeting to establish national school bus construction standards, including the adoption of a standard shade of paint. The color which became known as "school bus yellow" was selected because black lettering on that specific hue was easiest to see in the semi-darkness of early morning and late afternoon.

Officially, school bus yellow was designated "National School Bus Chrome" (currently renamed "National School Bus Glossy Yellow" following the removal of lead from the pigment). Although it is not a government specification outside of the United States and Canada, the association of yellow with school buses has led to the use of the color (in part or in whole) on school-use buses around the world. Some areas establishing school transport services have conducted evaluations of American yellow-style school buses,[37] while other governments have established their own color requirements, favoring other high-visibility colors (such as white or orange[14][38]) that better suit local climate conditions.

Retroreflective markings

School buses often operate in low-visibility conditions, such as early morning, or in poor weather, as well as in rural areas. While their yellow paint color does give them a conspicuity advantage over other vehicles, darkness can make them hard to see. To improve their visibility, many state and provincial governments (for example, Colorado)[39] require the use of yellow reflective tape on school buses.

Marking the length, width, height, and in some cases, identifying the bus as a school bus, reflective tape makes the vehicle easier to see in low light, also marking all emergency exits (so rescue personnel can quickly find them in darkness).[40]

The equivalent requirement in Canada is almost identical; the only difference is that red cannot be used as a retroreflective color.

Traffic priority

By the mid-1940s, most states had traffic laws requiring motorists to stop for school buses while children were loading or unloading. The justifications for this protocol are:

- Children, especially the younger ones, have normally not yet developed the mental capacity to fully comprehend the hazards and consequences of street-crossing, and under U.S. tort laws, a child cannot legally be held accountable for negligence. For the same reason, adult crossing guards often are deployed in walking zones between homes and schools.

- It is impractical in many cases to avoid children crossing the traveled portions of roadways after leaving a school bus or to have an adult accompany them.

- The size of a school bus generally limits visibility for both the children and motorists during loading and unloading.

Since at least the mid-1970s, all U.S. states and Canadian provinces and territories have some sort of school bus traffic stop law; although each jurisdiction requires traffic to stop for a school bus loading and unloading passengers, different jurisdictions have different requirements of when to stop. Outside of North America, the school bus stopping traffic to unload and load children is not provided for. Instead of being given traffic priority, fellow drivers are encouraged to drive with extra caution around school buses.

Warning lights and stop arms

Around 1946, the first system of traffic warning signal lights on school buses was used in Virginia. This system comprised a pair of sealed beam lights similar to those employed in American headlamps of the time. Instead of colorless glass lenses, the warning lights utilized red lenses. A motorized rotary switch applied power alternately to the red lights mounted at the left and right of the front and rear of the bus, creating a wig-wag effect. Activation was typically through a mechanical switch attached to the door control. However, on some buses (such as Gillig's Transit Coach models and the Kenworth-Pacific School Coach) activation of the roof warning lamp system was through the use of a pressure-sensitive switch on a manually controlled stop paddle lever located to the left of the driver's seat below the window. Whenever the pressure was relieved by extending the stop paddle, the electric current was activated to the relay. Plastic lenses for warning lights were developed in the 1950s, though sealed beams—now with colorless glass lenses — were still most commonly used behind them until the mid-2000s, when light-emitting diodes (LEDs) began supplanting the sealed beams.

With the adoption of FMVSS 108 in January 1968, four additional warning lights were gradually added to school buses; these were amber in color and mounted inboard of the red warning lights.[41] Intended to signal an upcoming stop to drivers, as the entry door was opened at the stop, they were wired to be overridden by the red lights and the stop sign.[41] Although 8-light systems were adopted by many states and provinces during the 1970s and 1980s, the all-red systems remain in use by some locales such as Saskatchewan and Ontario, Canada, as well as on buses built in Wisconsin before 2005 [42] and older buses in California.

To aid visibility of the bus in inclement weather, school districts and school bus operators add flashing strobe lights to the roof of the bus. Some states (for example, Illinois)[43] require strobe lights as part of their local specifications.

During the early 1950s, states began to specify a mechanical stop signal arm which the driver would swing out from the left side of the bus to warn traffic of a stop in progress. The portion of the stop arm protruding in front of traffic was initially a trapezoidal shape with stop painted on it. The U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 131 regulates the specifications of the stop arm as a double-faced regulation octagonal red stop sign at least 45 cm (17.7 in) across, with white border and uppercase legend. It must be retroreflective and/or equipped with alternately flashing red lights. As an alternative, the stop legend itself may also flash; this is commonly achieved with red LEDs.[44] FMVSS 131 stipulates that the stop signal arm be installed on the left side of the bus, and placed so that when it is extended, the arm is perpendicular to the side of the bus, with the top edge of the sign parallel to and within 6 inches (15 cm) of a horizontal plane tangent to the bottom edge of the first passenger window frame behind the driver's window, and that the vertical center of the stop signal arm must be no more than 9 inches (23 cm) from the side of the bus. One stop signal arm is required; a second may also be installed.[44] The second stop arm, when it is present, is usually mounted near the rear of the bus, and is not permitted to bear a stop or any other legend on the side facing forward when deployed.[44]

The Canadian standard defined in Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standard No. 131, is substantially identical to the U.S. standard.[45]

Safety devices

.jpg)

In addition to the warning devices that allow them to stop traffic around them when picking up or dropping off students, school buses are also equipped with a number of different safety devices to prevent accidents or injuries and for the purposes of security.

Emergency exits

For the purposes of evacuation, school buses are equipped with a minimum of at least one emergency exit in addition to the main entry door. The rear-mounted emergency exit door is a design feature retained from when school buses were horse-drawn wagons and the entrance door was rear-mounted to avoid frightening the horses; in rear-engine school buses, the door is replaced by an exit window supplemented by a side-mounted exit door.

Additional exits may be located in the roof (roof hatches), window exits, and/or side emergency exit doors. All are opened by the use of quick-release latches which activate an alarm. The number of emergency exits in a school bus depends on the size of the bus (its seating capacity) along with individual state regulations; Kentucky requires the most, with each full-size school bus having a total of eight emergency exits in addition to the entry door.

Loading and unloading

To inhibit pedestrians from walking close enough to the front of the bus that the hood obscures them from the driver's view, some states, such as North Carolina and Connecticut, require school buses to be equipped with crossing arms. These are devices which extend from the front bumper while the bus is stopped for loading or unloading.[46] By design, these force passengers to walk forward several feet forward of the bus (into the view of the driver) before they can walk across the road.

In the past, handrails in the entry way posed a potential risk to students; as they exited the bus, items such as drawstrings or other loose clothing could be caught if the driver was unaware and pulled away with the student caught in the door. To minimize this risk, school bus manufacturers have redesigned handrails and equipment in the stepwell area. In its School Bus Handrail Handbook, the NHTSA described a simple test procedure for identifying unsafe stepwell handrails.[47]

Video surveillance

During the past two decades, video cameras have become common equipment installed inside school buses, primarily to monitor and record passengers' behavior. Video cameras have also been useful in determining the causes of accidents: on March 28, 2000, a Murray County, Georgia, school bus was hit by a CSX freight train at an unsignaled railroad crossing; three children were killed. The bus driver claimed to have stopped and looked for approaching trains before proceeding across the tracks, as is required by law, but the onboard camera recorded that the bus had in fact not stopped.[48]

As digital recording devices replace VHS cameras, a single device is replaced by multiple cameras throughout the bus, allowing for surveillance from multiple vantage points. Exterior-mounted cameras are mounted on the bus to photograph vehicles illegally passing the school bus when its stop arm and warning lights are in use (thus committing a moving violation).

Seat belts

In contrast to cars and other light-duty passenger vehicles, school buses are typically not equipped with passenger seat belts. In 1977, as provided in Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) 222, the U.S. federal government required passive restraint and more stringent structural integrity standards for school buses instead of requiring lap seat belts. The passive restraint standards exempted school buses with a gross vehicle weight (GVWR) of over 10,000 pounds (4,5 metric tonnes) from requiring seat belts. A revised FMVSS 222 was set to take effect in October 2011 to require three-point, lap/shoulder belts in all newly manufactured Type A small school buses to improve occupant protection. The revised standard also introduces standards for testing lap/shoulder belt-equipped bus seats and the anchor points for the optional installation of these seat-belt systems in large school buses. Where in the past, FMVSS 222 seat belt equipped seats could reduce passenger capacity by up to one third, NHTSA is recognizing new technology that allows using seatbelts for either three small (elementary-age) children or two larger children (high-school age) per seat.[49][50]

Whether seat belts should be a requirement has been a topic of controversy.[51] In October 2013, the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services (NASDPTS) most recently stated at their annual transportation conference (NAPT) that they now fully support three-point lap-shoulder seat belts on school buses.[52] As of 2015, they are a requirement in at least five states:[53] California, Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Texas. Of the states that equip buses with two-point lap seat belts (Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey and New York), only New Jersey requires seat belt usage by riders.[54] In other states, it is up to the district or operator whether to require riders to use them or not.

In July 2004, California became the first state to require three-point lap/shoulder seat belts on all new Type A small school buses. A year later, this requirement was extended to large Type C and Type D school buses. Texas had planned a voluntary adoption of seat belts in newly purchased large school buses by 2010, with the state reiumbursing school districts for the additional costs. However, due to budget cuts, only 36% of the planned funding was allocated for the extra costs[55]

Compartmentalization

In 1967 and 1972, as part of an effort to improve crash protection in school buses, researchers at UCLA would play a role in the development of the interior design for school buses that was phased in by the end of the 1970s. Using the metal-backed seats then in use as a means of comparison, several new seat designs were tested. In its conclusion, the UCLA researchers found that the safest design was a 28-inch high padded seatback spaced a maximum of 24 inches apart, using the concept of compartmentalization as a passive restraint.[56] While the UCLA researchers found the compartmentalized seats to be the safest design, they found active restraints (such as seatbelts) to be next in terms of importance of passenger safety.[56]

In 1977, FMVSS 222 mandated a change to compartmentalized seats, though the height requirement was lowered to 24 inches.[50]

According to the NTSB, the main disadvantage of the design is its lack of protection in side-impact collisions (with larger vehicles) and rollover situations.[56] Though by design, students are protected front to back by compartmentalization, it allows the potential for ejection in other crash situations (however rare).[56]

School buses and the environment

In theory, school buses affect pollution in the same manner as carpooling; on average, each school bus transports the same number of students as 36 vehicles separately.[57] While busing transports students on a much larger scale than by car, the use of internal-combustion engines is not completely pollution-free (when compared to biking or walking).

As of 2017, over 90% of school buses in North America are powered by diesel-fueled engines.[58] While the design offers higher fuel efficiency over gasoline, health problems related to exposure from diesel exhaust fumes have become a concern.[59] Since the early to mid-2000s, emissions standards for diesel engines have been upgraded considerably; a school bus meeting 2017 emissions standards is 60 times cleaner than a school bus from 2002 (and approximately 3,600 times cleaner than a counterpart from 1990).[58][60] To comply with upgraded standards and regulations, diesel engines have been redesigned to use ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel with selective catalytic reduction becoming a common emissions control strategy.

Alternative fuels

Although diesel fuel is most commonly used in large school buses (and even in many smaller ones), alternatives such as LPG/propane and CNG have been developed to counter the drawbacks that diesel and gasoline-fueled school buses pose to the public health and environment.

The use of propane as a fuel for school buses began in the 1970s, largely as a response to the 1970s energy crisis. Initially produced as conversions of gasoline engines (as both require spark ignition), propane fell out of favor in the 1980s as fuel prices stabilized, coupled with the wider usage of diesel engines. In the late 2000s, propane-fueled powertrains reentered production, as emissions regulations began to negatively affect the performance of diesel engines. In 2009, Blue Bird Corporation introduced a version of the Blue Bird Vision powered by a LPG-fuel engine.[61] As of 2018, three manufacturers offer a propane-fuel full-size school bus (Blue Bird, IC, and Thomas), along with Ford and General Motors Type A chassis.

Compressed natural gas was first introduced for school buses in the early 1990s (with Blue Bird building its first CNG bus in 1991 and Thomas building its first in 1993)[61][62] As of 2018, CNG is offered by two full-size bus manufacturers (Blue Bird, Thomas) along with Ford and General Motors Type A chassis.[61][63]

Electric school buses

In theory, urban and suburban routes prove advantageous for the use of an electric bus; charging can be achieved before and after the bus is transporting students (when the bus is parked). In the early 1990s, several prototype models of battery-powered buses were developed as conversions of existing school buses; these were built primarily for research purposes.

During the 2000s, school bus electrification shifted towards the development of diesel-electric hybrid school buses. Intended as a means to minimize engine idling while loading/unloading passengers and increasing diesel fuel economy[64], hybrid school buses failed to gain widespread acceptance. A key factor in their market failure was their high price (nearly twice the price of a standard diesel school bus) to and hybrid system complexity.[65]

In the 2010s, several fully electric school buses would enter the marketplace. Trans Tech Bus would produce two designs, the eTrans (based on the Smith Electric Newton cabover truck),[66] and the SST-e, a conversion of the Ford E-Series. Lion Bus introduced the eLion conventional, the first full-size electric school bus, in 2015. In 2017, several manufacturers added electric school buses to their product ranges, with electric versions of the Blue Bird All American, Blue Bird Vision, Micro Bird G5 on ford E450 Chassis, IC CE-Series, and Thomas Saf-T-Liner C2 making their debut for future production.

Other uses

The basic bodies of school buses are also used in the construction of a variety of other vehicles, both as new vehicles and as conversions of retired school buses. Qualities desired from school bus bodies involve sturdy construction (as school buses have an all-steel body and frame), a large seating capacity, and wheelchair lift capability, among others.

In law enforcement

Larger police agencies may own their own police buses for a number of purposes derived from school bus bodies. Along with buses with high-capacity seating serving as officer transports (in large scale deployments), other vehicles derived from buses may have little seating, serving as temporary mobile command centers; these vehicles are built from school bus bodyshells and fitted with agency-specified equipment.

Prisoner transport vehicles are high-security vehicles used to transport prisoners; a school bus bodyshell is fitted with a specially designed interior and exterior with secure windows and doors.

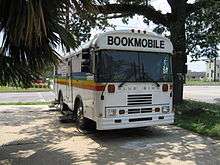

In community outreach

In terms of vehicles used for community outreach, school bus bodyshells (both new and second-hand) see use as bookmobiles and mobile blood donation centers (bloodmobiles), among other uses. Bookmobiles feature interior shelving for books and library equipment; bloodmobiles feature mobile phlebotomy stations and blood storage.

Both types of vehicles spend long periods of time parked in the same place; to reduce fuel consumption, they often have on-board electrical generators to power their interior equipment and climate control.

In church use

Churches throughout the United States and Canada use buses to transport their members, both to church services and to church events. In this capacity, many churches use vehicles based on school buses. Some churches own school buses purchased second-hand, while other churches own vehicles purchased new (other churches own minibuses with wheelchair lifts).

In nearly all cases, federal regulations require the removal of "School Bus" lettering and the disabling/removal of stop arms/warning lights.[2] In some states, the bus is required to change its color from School Bus Yellow entirely. In church use, transporting adults and/or children, traffic law no longer gives church buses traffic priority in most states (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia being the only states where a church bus can stop traffic with flashing red lights[67]).

Uses of retired school buses

As of 2016, the average age of a school bus in the United States is 9.3 years.[68] School buses can be retired from service due to a number of factors, including vehicle age or mileage, mechanical condition, emissions compliance, or any combination of these factors.[68] In some states and provinces, school bus retirement comes is called for at specific age or mileage intervals, regardless of mechanical condition. In recent years, budget concerns in many publicly funded school districts have necessitated that school buses be kept in service longer.

When a school bus is retired from school use, it can see a wide variety of usage. While a majority are scrapped for parts and recycling (a requirement in some states), better-running examples are put up for sale as surplus vehicles. Second-hand school buses are sold to such entities as churches, resorts or summer camps; others are exported to Central America, South America, or elsewhere. Other examples of retired school buses are preserved and restored by collectors and bus enthusiasts; collectors and museums have an interest in older and rarer models. Additionally, restored school buses appear alongside other period vehicles in television or film.

After a school bus is sold, NHTSA regulations require that the stop arms and warning signals of a school bus be removed or disabled.[2] If the bus is to transport passengers, the exterior must be painted a color other than school bus yellow and all school bus lettering must be removed.[2]

School bus conversions

.jpg)

In retirement, not all school buses live on as transport vehicles. In contrast, the purchasers of school buses use the large body and chassis to use as either a working vehicle, or as a basis to build a rolling home. To build a utility vehicle for farms, owners often remove much of the roof and sides, creating a large flatbed or open-bed truck for hauling hay. Other farms use unconverted, re-painted, school buses to transport their workforce.

Skoolies are retired school buses converted into recreational vehicles (the term also applies to their owners and enthusiasts). While some examples are fairly primitive, others rival production-built RVs in equipment and quality. Exteriors can range from conservative designs to the bus equivalent of an art car.

An example of a school bus converted to an RV is the 1946 International Harvester school bus abandoned on the Stampede Trail in Alaska where Christopher McCandless lived and died in 1992 (often referred to as the "Magic School Bus").

School bus export

Retired school buses from Canada and the United States are sometimes exported to Africa, Central America, South America, or elsewhere. Used as public transportation between communities, these buses are nicknamed "chicken buses" for both their crowded accommodation and the (occasional) transportation of livestock alongside passengers. To attract passengers (and fares), yellow buses are often repainted with flamboyant exterior color schemes and modified with chrome exterior trim.

Around the world

Outside the United States and Canada, purpose-built school buses for student transport are less common. In Europe, Asia, and Australia, buses for this purpose may be standard transit buses, differing primarily only by routing and signage.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "National School Transportation Specifications and Procedures 2015 Edition" (PDF). pp. 342–343.

- 1 2 3 4 Highway Safety Program Guidelines: Pupil Transportation Safety Archived 2011-12-31 at the Wayback Machine.. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration website. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ "School Bus Fleet, Factbook 2016". digital.schoolbusfleet.com. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- ↑ "FAQs". American School Bus Council. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ "National Center for Education Statistics|Fast Facts". Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Mark Theobald (2004). Wayne Works. Coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 2010-04-26

- 1 2 Gray, Ryan (August 1, 2007). "The History of School Transportation". School Transportation News. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ Mark Theobald (2004). "Crown Coach". Coachbuild.com. Retrieved 2010-04-29

- 1 2 J. H. Valentine. "Crown Coach: California's Specialty Builder". Tripod. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- 1 2 Sandi Brockway (January 11, 2007). "Crown Coach Corporation (1932–1991)". Crown Coach Historical Society. Retrieved 2010-04-28

- ↑ "The Gillig Transit Coach And Pacific Schoolcoach Online Museum (archived)". Archived from the original on January 19, 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Frank W. Cyr, 'Father of the Yellow School Bus,' Dies at the Age of 95". Columbia University press release (August 3, 1995). Retrieved 2010-04-07

- ↑ "School Bus Safety Community Advisory Committee" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- 1 2 "WA School Bus Specifications 20 September 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- 1 2 "Blue Bird, School Bus, History, Blue Bird Body Co., Blue Bird Corp., Wanderlodge, Buddy Luce, Albert L. Luce, Cardinal Mfg., Fort Valley, Georgia - CoachBuilt.com". www.coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- 1 2 "Ward Body Works, Ward School Bus Mfg., IC Bus, Ward School Bus history, David H. Ward, Dave Ward, AmTran, Navistar, IC Corp., Conway, Arkansas - CoachBuilt.com". www.coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ↑ "Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards". School Transportation News. August 8, 2009. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ "Blue Bird, Girardin Join Forces". School Bus Fleet Magazine. February 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "FAQs/Q: The school bus looks like it's hardly changed in decades. Where's the modernization". American School Bus Council. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

- ↑ "Spartan Chassis Executes Agreement With Lion Bus Inc. for Type C School Bus Chassis". MarketWatch. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "IC Bus Unveils Gasoline-Powered Type C School Bus – Management – School Bus Fleet". www.schoolbusfleet.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Blue Bird Introduces All-New Electric School Bus Solutions | News | Press Releases | blue-bird". www.blue-bird.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ Spiral Design Studio. "School Bus GPS Tracking – Busfinder from". Transfinder. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ "School Bus Tracking". Vainatheya.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ "School Bus Fleet, Factbook 2016". digital.schoolbusfleet.com.

- ↑ "School Bus Fleet Fact Book 2014". 59 (11): 34.

- ↑ "National School Transportation Specifications and Procedures 2015 Edition" (PDF). p. 59.

- ↑ The Fourteenth National Congress on School Transportation. "National School Transportation Specifications and Procedures (2005 Revised Edition)" (PDF). p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2014. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "School bus types". School Transportation News. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Are there other vehicles that can be used for school transportation? Vans?". Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Why do some school buses look different than others, for example in color?". Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Dr Kristin Poland of NTSB, quoted at a hearing into a fatal 2012 bus crash at Chesterfield, Missouri, in "Buses safer than cars", Circular, Bus and Coach Association of New Zealand, August 2013.

- ↑ amy.lee.ctr@dot.gov (2016-09-09). "School Bus Safety". NHTSA. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- ↑ "After Deadly New Jersey Crash, Scrutinizing the Safety of School Buses". 18 May 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ↑ "Protecting Children from Their Own Buses by Mark D. Fisher". Retrieved January 29, 2006.

- ↑ Rob Watson (June 13, 2000). "UK may get yellow school buses". BBC News. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Sydney Metropolitan Bus Service Contract-Schedule 8" (PDF). Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ↑ Colorado Minimum Standards Governing School Bus Transportation Vehicles Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Colorado Code of Regulations 301-25, Section 2251-R-54.02. Retrieved 2010-04-16

- ↑ Bus emergency exits and window retention and release Code of Federal Regulations Title 49, Section 571.217. Retrieved 2010-04-15

- 1 2 "Code of Federal Regulations Title 49, Volume 6, Section 571.108" (PDF): 361.

- ↑ Wisconsin Legislature 347.25 (2) Wisconsin Statutues Chapter 347 (EQUIPMENT OF VEHICLES) Retrieved 2016-09-18

- ↑ Illinois school bus safety standards: Lamps, Reflectors, Signals Illinois Administrative Code Title 92 (Transportation), Sec. 442.615g. Retrieved 2010-04-16

- 1 2 3 School bus pedestrian safety standards Code of Federal Regulations Title 49, Section 571.131. Retrieved 2010-4-15.

- ↑ "Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standard – Technical Standards Document 131". Tc.gc.ca. 2011-04-04. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ Safety in the Danger Zone School Bus Fleet (September 1, 2007). Retrieved 2010-04-19

- ↑ Handrail Mechanics School Bus Handrail Handbook. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ↑ Highway Accident Report – NTSB/HAR-01/03 National Transportation Safety Board (December 11, 2001). Retrieved 2012-07-28

- ↑ Ryan Gray (August 7, 2009). "School Bus Seat Belts FAQ". School Transportation News. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - 1 2 "School Bus Seat Belts". School Transportation News. Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Janna Morrison (August 8, 2008). "NAPT Advocates Scientific Approach to Seat Belt Issue". School Transportation News. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Arroyo, Silvia (24 October 2013). "NASDPTS Alters Its Support of Three-Point Lap/Shoulder Seat Belts on School Buses". School Transportation News. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Susan Haigh (February 17, 2010). "Connecticut considers installing seat belts on school buses". The Hour Online. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Seat Belts in School Buses Transport Canada. Retrieved 2010-04-19

- ↑ Ryan Gray (July 8, 2009). "The History of Seat Belt Development". School Transportation News. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- 1 2 3 4 "Compartmentalization". 2012-02-02. Archived from the original on 2012-02-02. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ "Individual, Local and Global Community Impact". American School Bus Council. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- 1 2 "The Smart School Transportation Choice". https://www.dieselforum.org. Retrieved 2018-03-23. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ https://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2012/pdfs/pr213_E.pdf

- ↑ "FAQs/Q: Is it healthy for my child to ride the school bus?". American School Bus Council. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

- 1 2 3 Blue Bird's Alternative Fuel Product Offerings Archived 2010-07-24 at the Wayback Machine. Blue Bird Corporation. Retrieved 2010-4-16

- ↑ "Thomas school bus history,Perley A. Thomas Car Works, Thomas Built Buses, Thomas Built Buses div. of Freightliner, Thomas Built Buses div. of Daimler Trucks, High Point, N.C. - CoachBuilt.com". www.coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- ↑ Saf-T-Liner HDX Thomas Built Buses (pdf brochure). Retrieved 2010-04-16

- ↑ "IC Corporation Works with Enova Systems to Supply First Hybrid School Buses That Can Attain Up To 40 Percent Increase in Fuel Efficiency". Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ "Hybrids Might be the Way of the Future but Remain Slow in Coming to School Transportation Industry". Stnonline.com. 2011-03-04. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ "Trans Tech goes green with electric school bus". Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "LIS § 46.2–917.1. School buses hired to transport children". Code of Virginia. Retrieved December 4, 2005.

- 1 2 "School Bus Fleet Factbook 2016". pp. 46–50. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to School buses. |

- School Bus Fleet Magazine – news magazine for student transportation professionals

- School Transportation News – news magazine for student transportation professionals

- U.S. DOT, NHTSA, Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards for School Buses (FMVSS)

- School Bus Driver Steers Students Toward Love Of Reading Video produced by Wisconsin Public Television

_Arriva_London_New_Routemaster_(19522859218).jpg)