Pullman Company

The Pullman Car Company, founded by George Pullman, manufactured railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late nineteenth century development of mass production, and takeover of rivals, the company developed a virtual monopoly on production and ownership of sleeper cars. At its peak in the early 20th century, its cars accommodated 26 million people a year, and it in effect operated "the largest hotel in the world".[1] Its production workers initially lived in a planned worker community (or "company town") named Pullman, Chicago.[2] Pullman developed the sleeping car, which carried his name into the 1980s. Pullman did not just manufacture the cars, he also operated them on most of the railroads in the United States, paying railroad companies to couple the cars to trains. The labor union associated with the company, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded and organized by A. Philip Randolph, was one of the most powerful African-American political entities of the 20th century. The company also built thousands of streetcars[3] and trolley buses for use in cities.[4] Post World War II changes in automobile and airplane transport led to a steep decline in the company's fortunes. It folded in 1968.

History

After spending the night sleeping in his seat on a train trip from Buffalo to Westfield, New York, George Pullman was inspired to design an improved passenger railcar that contained sleeper berths for all its passengers. During the day, the upper berth was folded up overhead somewhat like a modern airliner's overhead luggage compartment. At night, the upper berth folded down and the two facing seats below it folded over to provide a relatively comfortable lower berth. Although this was a somewhat spartan accommodation by today's standards, it was a great improvement on the previous layout. Curtains provided privacy, and there were washrooms at each end of the car for men and women. The first Pullman coach was built at the Chicago & Alton shops in Bloomington, Illinois in the spring of 1859 with the permission of Chicago & Alton President Joel A. Matteson.

Pullman established his company in 1862 and built luxury sleeping cars which featured carpeting, draperies, upholstered chairs, libraries, card tables and an unparalleled level of customer service. Patented paper car wheels provided a quieter and smoother ride than conventional cast iron wheels from 1867 to 1915.[5][6][7] Once a household name due to their large market share, the Pullman Company is also known for the bitter Pullman Strike staged by their workers and union leaders in 1894. During an economic downturn, Pullman reduced hours and wages but not rents, precipitating the strike. Workers joined the American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs.

Exterior view of a Pullman car.

Exterior view of a Pullman car. A Pullman car, interior view.

A Pullman car, interior view. Upper and lower berth

Upper and lower berth.jpg) Coach built in 1890 by Pullman for the B&O Royal Blue, now at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, Maryland

Coach built in 1890 by Pullman for the B&O Royal Blue, now at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, Maryland- The Federal #98 Pullman Private Car. This Pullman Private Car, which was available for lease, was built by the Pullman Company in 1911.

- The Santa Fe Business Car #405, also known as the Superintendent's Car, was one of eighteen cars built in 1927 by the Pullman Company as part of the fourth order of business cars for division superintendents

Built in 1928, the 'Amundsen', on different occasions reportedly carried Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower

Built in 1928, the 'Amundsen', on different occasions reportedly carried Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower

After George Pullman's death in 1897, Robert Todd Lincoln, son of Abraham Lincoln, became company president. The company closed its factory in the Pullman neighborhood of Chicago in 1955. Pullman purchased the Standard Steel Car Company in 1930 amid the Great Depression, and the merged entity was known as Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Company. The company ceased production after the Amtrak Superliner cars in 1982 and its remaining designs were purchased in 1987 when it was absorbed by Bombardier.

Corporate history

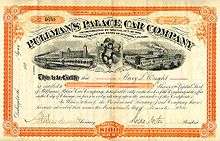

The original Pullman Palace Car Co. had been organized on February 22, 1867.

On January 1, 1900, after buying numerous associated and competing companies, it was reorganized as The Pullman Co., characterized by its trademark phrase, "Travel and Sleep in Safety and Comfort."

In 1924, Pullman Car & Manufacturing Co. was organized from the previous Pullman manufacturing department, to consolidate the car building interests of The Pullman Co. The parent company, The Pullman Co., was reorganized as Pullman, Inc., on June 21, 1927.

The best years for Pullman were the mid-1920s. In 1925, the fleet grew to 9800 cars. Twenty-eight thousand conductors and twelve thousand porters were employed by the Pullman Co.[8] Pullman built its last standard heavyweight sleeping car in February 1931.

Pullman purchased controlling interest in Standard Steel Car Company in 1929, and on December 26, 1934, Pullman Car & Manufacturing (along with several other Pullman, Inc. subsidiaries), merged with Standard Steel Car Co. (and its subsidiaries) to form the Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Company. Pullman-Standard remained in the rail car manufacturing business until 1982. Standard Steel Car Co., had been organized on January 2, 1902, to operate a railroad car manufacturing facility at Butler, Pennsylvania (and, after 1906, a facility at Hammond, Indiana), and was reorganized as a subsidiary of Pullman, Inc., on March 1, 1930.

In 1940, just as orders for lightweight cars were increasing and sleeping car traffic was growing, the United States Department of Justice filed an anti-trust complaint against Pullman Incorporated in the U.S. District Court at Philadelphia (Civil Action No. 994). The government sought to separate the company's sleeping car operations from its manufacturing activities. In 1944, the court concurred, ordering Pullman Incorporated to divest itself of either the Pullman Company (operating) or the Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Company (manufacturing). After three years of negotiations, the Pullman Company was sold to a consortium of fifty-seven railroads for around US$40 million.[9]

In 1943, Pullman Standard established a shipbuilding division and dived into wartime small ship design and construction. The yard was located near Lake Calumet in Chicago, on the north side of 130th Street, at the most southerly point of Lake Michigan. Pullman built the boats in 40-ton blocks which were assembled in a fabrication shop on 111th Street and moved to the yard on gondola cars. In two years, the company built 34 Corvette PCEs, which were 180 feet long and weighed 640 tons, and 44 LSMs, which were 203 feet long and weighed 520 tons. Pullman ranked 56th among United States corporations in the value of World War II military production contracts.[10]

Pullman-Standard built its last sleeping car in 1956[11] and its last lightweight passenger cars in 1965, an order of ten coaches for Kansas City Southern.[12] The company continued to market and build cars for commuter rail and subway service and Superliners for Amtrak as late as the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Beginning in 1974, Pullman delivered seven hundred and fifty 75 ft (23 m) stainless steel subway cars to the New York City Transit Authority. Designated R46 by their procurement contract, these cars, along with the R44 subway car built by St. Louis Car Company, were designed for 70 mph (110 km/h) speeds in the Second Avenue Subway; after it was deferred in 1975, the Transit Authority assigned the cars to other subway services. Pullman also built subway cars for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, which assigned them to the Red Line. Pullman-Standard was spun off from Pullman, Inc., as Pullman Technology, Inc., in 1981, and was sold to Bombardier in 1987.

Pullman antitrust case

In United States v. Pullman Co., 50 F. Supp. 123, 126, 137 (E.D. Pa. 1943), the company was ordered to divest itself of one of its two lines of sleeping car businesses after having acquired all of its competitors.

The end of Pullman

After the 1944 breakup, Pullman, Inc., remained in place as the parent company, with the following subsidiaries: The Pullman Company for passenger car operations (but not passenger car ownership, which was passed to the member railroads), and Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Co., for passenger car and freight car manufacturing; along with a large freight car leasing operation still directly under the parent company's control. Pullman, Inc., remained separate until a merger with Wheelabrator, then headed by CEO Michael D. Dingman, in late 1980, which led to the separation of Pullman interests in early and mid-1981.

Operations of the Pullman Company sleeper cars ceased and all leases were terminated on December 31, 1968.[11][13] On January 1, 1969, the Pullman Company was dissolved and all assets were liquidated. (The most visible result on many railroads, including Union Pacific, was that the Pullman name was removed from the letterboard of all Pullman-owned cars.) An auction of all Pullman remaining assets was held at the Pullman plant in Chicago in early 1970. The Pullman, Inc., company remained in place until 1981 or 1982 to close out all remaining liabilities and claims, operating from an office in Denver.

The passenger car designs of Pullman-Standard were spun off into a separate company called Pullman Technology, Inc., in 1982. Using the Transit America trade name, Pullman Technology continued to market its Comet car design (first built for New Jersey Department of Transportation in 1970) for commuter operations until 1987, when Bombardier purchased Pullman Technology to gain control of its designs and patents. As of late 2004, Pullman Technology, Inc., remained a subsidiary of Bombardier.

Pullman, Inc., spun off its large fleet of leased freight rail cars in April 1981 as Pullman Leasing Company, which later became part of ITEL Leasing, retaining the original PLCX reporting mark. ITEL Leasing (including the PLCX reporting mark) was later changed to GE Leasing.

In mid-1981, Pullman, Inc., spun off its freight car manufacturing interests as Pullman Transportation Company. Several plants were closed and in 1984, the remaining railcar manufacturing plants and the Pullman-Standard freight car designs and patents were sold to Trinity Industries.

After separating itself from its rail car manufacturing interests, Pullman, Inc., continued as a diversified corporation, with later mergers and acquisitions, including a merger in late 1980 with Wheelabrator-Frye, Inc., in which Pullman became a subsidiary of Wheelabrator-Frye, Inc. In January 1982, Wheelabrator-Frye merged with M. W. Kellogg, a builder of large, cast-in-place smokestacks, silos and chimneys. Wheelabrator-Frye retained both Pullman and Kellogg as direct subsidiaries. Later in 1982 Signal acquired Wheelabrator-Frye.[14] In 1990, the entire Wheelabrator-Frye group was sold to Waste Management, Inc. The Pullman-Kellogg interests were spun off by Waste Management as Pullman Power Products Corporation, and by late 2004 that company was doing business as Pullman Power LLC, a subsidiary of Structural Group, a specialty contractor.

As a separate side note, other construction engineering portions of Pullman-Kellogg were spun off as a new M. W. Kellogg Corporation, and in December 1998, became part of the merger that formed Kellogg, Brown & Root, a specialty contractor which itself was later sold to Halliburton, an oil well servicing company. In an eventual competitive move, other Kellogg engineering interests were merged with Rust Engineering becoming Kellogg Rust, which itself became The Henley Group, and later Rust International before it became the Rust Division of what is today Washington Group International, a specialty contracting firm that competes directly with Halliburton worldwide. Washington Group International is the successor to the Morrison Knudsen civil engineering and contracting corporation, and is also the owner of Montana Rail Link.

After the last of the Kellogg interests of Pullman-Kellogg were spun off, and after the railcar manufacturing plants were sold, and with the formal dissolution of the old Pullman Company (the operating company from the 1944 split), the remaining portions of the Pullman interests were spun off in May 1985 by Signal into a new Pullman Company. In November 1985, Pullman bought Peabody International and the new company took the new name of Pullman Peabody. In April 1987 (after Pullman Technology was sold to Bombardier), the name was changed back to Pullman Company. In July 1987 the company acquired Clevite Industries.[15] By 1996, Pullman Co., with its Clevite subsidiary, was almost solely a supplier of automotive elastomer (rubber) parts, and in July 1996 the company was sold to Tenneco. As of late 2004, Pullman Co. (now the brand name Clevite), as a manufacturer of automotive elastomer products, was still under the control of Tenneco Automotive.

Company town

In 1877, the United States experienced the Great Railroad Strike. Part of its legacy included more powerful unions and a tendency for employers to consider the broader well-being of their employees. Pullman's objective in building a company town was to attract a superior type of employee and further elevate these individuals by excluding baneful influences.[16] In late April 1880, George Pullman announced his plans to build a company town and factory. Pullman's plan included an expectation that rent collected on the houses in the town would produce a 6 percent return on investment (ROI). However, it appears the ROI never exceeded 4 – 4½ %.[17]

The company built Pullman, Illinois on 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), 14 mi (23 km) south of Chicago, contracting Solon Spencer Beman for design and Nathan F. Barrett for landscaping. Both were considered experts in their respective fields. Beman interned under well-known architect Richard Upjohn. Barrett landscaped areas in Staten Island and Tuxedo, New York, as well as Long Branch, New Jersey. George Pullman's governing concept placed the town not within the city limits of Chicago but in the adjoining town of Hyde Park. On April 24, 1880, groundwork began. Throughout construction, Pullman sought to minimize costs and maximize efficiency adopting techniques of mass production whenever possible. Some of the earliest departments and shops created included painting, iron, and woodworking. These could then be employed to contribute to continuing construction.[18] By January 1, 1881, the town was ready for its first resident to move in. A foreman from the Pullman Company's Detroit shop, Lee Benson, moved his wife, child, and sister into the town.[19] Building exteriors were red brick with limestone trim. Interiors featured high ceilings and large windows. Interior walls were purposefully painted in light colors with the objective of providing a cheerful environment.[20] When completed, the town included a library, theater, hotel, church, market, sewage farm, park, and many residential buildings. The bar in the Florence Hotel was the only place within the town limits where alcohol could be served and consumed.[21] In the residential section, 150 acres were dedicated to tenements, flats and single-family homes with rents from $0.50 to $0.75 per month.[22] The residences featured modern conveniences such as gas, running water, indoor sewage plumbing and regular garbage removal. By 1884, there were more than 1,400 tenements and flats. By July of the following year the population exceeded 8,600.[23]

In charge of the company town was the town agent who was responsible for all services and businesses including street and building maintenance, gas and water works, fire protection, the hotel, sewage farm, and the nursery and greenhouse. Reporting to the town agent were nine department heads and approximately 300 men.[24] With the exception of the school board there were no elections. All officials were selected by Pullman.[25]

After its completion, the Pullman company town attracted national attention. Many critics praised Pullman's concept and planning. One newspaper article titled "The Arcadian City: Pullman, the Ideal City of the World" praised the town as "the youngest and most perfect city in the world, Pullman; beautiful in every belonging."[26] In February 1885, Harper's Monthly published and article by Richard T. Ely entitled "Pullman: A Social Study". Though the article offered praise for creating an elevated environment for its workers, it criticized the all-encompassing influence of the company ultimately concluding that "Pullman is un-American" and "benevolent, well-wishing feudalism."[27]

During the Panic of 1893, Pullman closed his manufacturing plant in Detroit in order to move all manufacturing to Pullman.[28] Due to the soft economic conditions of this period, the Pullman Co. reduced wages and laid off employees. However, though wages were reduced, residential utility rates and rents remained unchanged. On May 11, 1894, the employees of the Pullman Co. walked off the job initiating the Pullman Strike. Thirty people were killed as a result of the strikes and sabotage. At the conclusion of the strike, perhaps due to a loss of pride, Pullman's company town was never the same.[29]

In February 1904, the Pullman Company was given a court order to sell the company town but delayed compliance until 1907.[30] Today, Pullman is a Chicago neighborhood, and a historical landmark district on the state, National Historic Landmark and National Register of Historic Places lists.

In 2014, the National Park Service initially considered the concept of turning Pullman into a new, urban National Park.[31] On February 19, 2015, Pullman's company town was established as a National Monument by President Barack Obama.[32]

Other Pullman sites

The Pullman Company operated several facilities in other areas of the U.S. One of these was the Pullman Shops in Richmond, California, which was linked to the mainline tracks of both the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe, servicing their passenger equipment from throughout the Western U.S. The main building of the Richmond Pullman Shops still exists, as does the thoroughfare it's located on: Pullman Avenue.

Porters

The Pullman Company was also noted for its porters. The company hired black men almost exclusively for the porter positions (Men of Filipino descent were primarily hired for club car service positions). Although a porter's occupation was menial in some respects, it offered better pay and security than most jobs open to African Americans at the time, as well as an opportunity to travel the country. Many credit Pullman porters as significantly contributing to the development of America's black middle class.[33] In 1925, Pullman porters became unionized as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), founded by A. Philip Randolph. At one time Pullman was the largest employer of African Americans in the United States.[34]

Products

Rail vehicles

Pullman's streetcar building period lasted from 1891[3][4] until 1951.[35] The company one was one of just three builders (and one of only two in the U.S.) of the PCC streetcar, a standardized type of streetcar purchased by numerous North American transit systems between 1936 and 1952[36] and nearly 5,000 of which were constructed.[37] Pullman built the body of the very first all-new PCC car, a prototype called "model B", in 1934,[38] but the first production-series Pullman PCC cars were not built until 1938 (and delivered in early 1939).[35] The St. Louis Car Company captured about 75% of the U.S. market for PCC cars, with the balance of around 25% being supplied by Pullman.[35]

Trolley buses

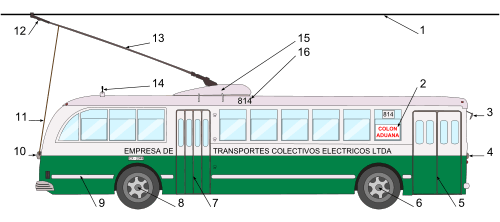

In addition to rail vehicles, Pullman-Standard also manufactured trolley buses — or trolley coaches, as they were more commonly known at the time – starting in 1931[39] and concluding in late 1952.[40] A total of 2,007 trolley buses were built by the company.[39] Production took place at a former Osgood Bradley Car Company plant in Worcester, Massachusetts, which had come under Pullman control as part of its 1929/30 acquisition of a controlling interest in the Standard Steel Car Company.[4] The vast majority were built for U.S. cities, with only 24 being supplied to Canadian cities and a total of 136 built for cities in South America.[39] The very last trolleybuses built were an order of 30 for Valparaíso, Chile, in late 1952.[40][41] That city's Pullman trolley buses have far outlasted any others, and as of 2015 about a dozen were still in regular service there,[42] four from the 1952 batch and the others from a larger group built in 1946–48 but partially rebuilt in 1987–88.[43] In 2003, the remaining 15 were declared a National Historic Monument by the Chilean government.[43][44]

A 1944 Pullman trolley bus that has been preserved in Seattle, for occasional public excursions

A 1944 Pullman trolley bus that has been preserved in Seattle, for occasional public excursions One of the Pullman-built trolley buses that are still in service in Valparaíso, Chile, in 2014

One of the Pullman-built trolley buses that are still in service in Valparaíso, Chile, in 2014 Interior of a Pullman-Standard trolley bus

Interior of a Pullman-Standard trolley bus Diagram of a 1947 Pullman-Standard trolley bus

Diagram of a 1947 Pullman-Standard trolley bus

See also

Notes

- ↑ Briggs, Martha T.; Perters, Cunthia H. (1995). "Pullman Company Archives". Newberry Library. p. v. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ↑ Super User. "South Shore Journal - Marktown: Clayton Mark's Planned Worker Community in Northwest Indiana". Archived from the original on September 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Middleton, William D. || || 1967). The Time of the Trolley, p. 424. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 0-89024-013-2.

- 1 2 3 Sebree, Mac; and Ward, Paul (1973). Transit's Stepchild, The Trolley Coach (Interurbans Special 58), p. 173. Los Angeles: Interurbans. LCCN 73-84356.

- ↑ John H. Lienhard: Engines of Our Enginuity, No. 758: Paper railroad wheels.

- ↑ Cupery, Ken (2016). "Paper Railroad Wheels?". cupery.net.

- ↑ J. Wallace: Pullman Palace Car Works: The Allen Paper Wheel Company.

- ↑ "Eliillinois". Eliillinois. Archived from the original on June 29, 2006.

- ↑ "Pullman Guide" (PDF). Newberry.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ↑ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.619

- 1 2 Bedingfield, Robert E. (November 23, 1968). "Rails Taking Over Sleeping Car Runs; Pullmans Moving Into Rails' Hands". New York Times. pp. 71, 77. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Drury, George H. (June 5, 2006), "Who built the streamliners: Historical profiles of North American passenger-car builders", TRAINS magazine, archived from the original on September 5, 2010, retrieved November 24, 2010

- ↑ "Pullman Conductor All but Disappears With End of 1968". New York Times. December 31, 1968. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Cole, Robert J. (1982-11-10). "Wheelabrator and Signal to Merge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Pullman Co. reports earnings for Qtr. to Sept 30". The New York Times. December 8, 1987. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ United States Strike Commission, Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July 1894 (Washington D.C., Government Printing Office, 1895), 529, accessed April 15, 2015

- ↑ United States Strike Commission, Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July 1894 (Washington D.C., Government Printing Office, 1895), 530, accessed April 15, 2015

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 52

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 53

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 57

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 65

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 71

- ↑ Smith, Carl (2007). Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 180-181

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 107-108

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 117

- ↑ "The Arcadian City," uncited newspaper clipping, accessed April 15, 2015, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2015. .

- ↑ Richard Ely, "Pullman: A Social Study," Harper's Monthly 70 (1885): 465, accessed April 15, 2015, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2015. .

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 139

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 206.

- ↑ Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 214

- ↑ "Chicago's Pullman site could become national park, Seattle-pi.com (August 23, 2014)". seattlepi.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ↑ "NPS Archeology Program: Antiquities Act Centennial". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ↑ Morning Edition (May 8, 2009). "Pullman Porters Helped Build Black Middle Class". NPR. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Reflections on Black History". Freepress.org. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Carlson, Stephen P.; and Schneider, Fred W. || || 1980). PCC: The Car That Fought Back, pp. 103–4. Glendale (CA): Interurban Press. ISBN 0-916374-41-6.

- ↑ Kashin and Demoro, p. 59.

- ↑ Kashin and Demoro, p. 81.

- ↑ Kashin and Demoro, p. 35–36.

- 1 2 3 Porter, Harry; and Worris, Stanley F.X. (1979). Trolleybus Bulletin No. 109: Databook II. Louisville (KY): North American Trackless Trolley Association (defunct).

- 1 2 Saitta, Joseph P. (ed.) (1987). Traction Yearbook '87, p. 111. Merrick (NY), US: Traction Slides International. ISBN 978-0-9610414-6-5. LCCN 81-649475.

- ↑ Murray, Alan (2000). World Trolleybus Encyclopaedia. Yateley, Hampshire, UK: Trolleybooks. p. 124. ISBN 0-904235-18-1.

- ↑ Trolleybus Magazine, September–October 2015, p. 152. UK: National Trolleybus Association. ISSN 0266-7452

- 1 2 Webb, Mary (ed.) (2009). Jane's Urban Transport Systems 2009–2010, pp. 65–66. Coulsdon (UK): Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2903-6.

- ↑ "Quince troles porteños so monumentos históricos". La Estrella (in Spanish). July 29, 2003. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

References

- Kashin, Seymour; and Demoro, Harre (1986). An American Original: The PCC Car. Glendale, CA (US): Interurban Press. ISBN 0-916374-73-4.

- Tye, Larry (2004). Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-7850-9.

- Welsh, Joe; Bill Howes (2004). Travel by Pullman: a century of service. Saint Paul, MN: MBI. ISBN 0760318573. OCLC 56634363.

- Knoll, Charles (1995). Go Pullman: Life and Times. Rochester, NY (US): (Rochester Chapter National Raillway Historical Society) ( ISBN 0-9605296-3-2)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pullman-Standard. |

- Pullman Company town today

- Pullman Shops of Richmond, California

- The Pullman Project this Web site focuses solely on Pullman's sleeper cars

- Smithsonian, Pullman Palace Car Company Collection, 1867–1979

- Pullman History at UtahRails.net Includes a timeline of the Pullman antitrust case.

- The Pullman Trolleybuses of Valparaíso

- Frank H. Beberdick Pullman Collection at Newberry Library

- Documents and clippings about Pullman Company in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

Pullman Company publications

- Pullman Accommodations illustrated brochure, 1934

- Pullman on Dress Parade illustrated brochure, 1948

- Go Pullman illustrated brochure, 1954