Francisco de Zurbarán

| Francisco Zurbarán | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Francisco de Zurbarán Baptized 7 November 1598 Fuente de Cantos, Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain |

| Died |

27 August 1664 (aged 65) Madrid, Spain |

| Residence | Seville (1614-1658), Madrid (1658-1664) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement |

Baroque Caravaggisti |

| Patron(s) |

Philip IV of Spain Diego Velázquez |

Francisco de Zurbarán (baptized November 7, 1598 – August 27, 1664) was a Spanish painter. He is known primarily for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns, and martyrs, and for his still-lifes. Zurbarán gained the nickname Spanish Caravaggio, owing to the forceful, realistic use of chiaroscuro in which he excelled.

Biography

Zurbarán was born in 1598 in Fuente de Cantos, Extremadura; he was baptized on November 7 of that year.[3][4][5] His parents were Luis de Zurbarán, a haberdasher, and his wife, Isabel Márquez.[4][5] In childhood he set about imitating objects with charcoal. In 1614 his father sent him to Seville to apprentice for three years with Pedro Díaz de Villanueva, an artist of whom very little is known.[6]

His first marriage, in 1617, was to María Paet who was nine years older. María died after the birth of their third child in 1624. In 1625 he married again to wealthy widow Beatriz de Morales. On January 17, 1626, Francisco de Zurbarán signed a contract with the prior of the Dominican monastery San Pablo el Real in Seville, agreeing to produce 21 paintings within eight months.[7] Fourteen of the paintings depicted the life of Saint Dominic; the others represented Saint Bonaventura, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Dominic, and the four Doctors of the Church.[8] This commission established Zurbarán as a painter. On August 29, 1628, Francisco de Zurbarán was commissioned by the Mercedarians of Seville to produce 22 paintings for the cloister in their monastery. In 1629, the Elders of Seville invited Zurbarán to relocate permanently to the city, as his paintings had gained such high reputation that he would increase the reputation of Seville. He accepted the invitation and moved to Seville with his wife Beatriz de Morales, the three children from his first marriage, a relative called Isabel de Zurbarán and eight servants. In May 1639 his second wife, Beatriz de Morales, died.

Towards 1630 he was appointed painter to Philip IV, and there is a story that on one occasion the sovereign laid his hand on the artist's shoulder, saying "Painter to the king, king of painters". After 1640 his austere, harsh, hard-edged style was unfavorably compared to the sentimental religiosity of Murillo and Zurbarán's reputation declined. Beginning by the late 1630s, Zurbarán's workshop produced many paintings for export to South America.[9]

On February 7, 1644, Francisco married a third time with another wealthy widow, Leonor de Torder. It was only in 1658, late in Zurbarán's life, that he moved to Madrid in search of work and renewed his contact with Velázquez.[9] Popular myth has Zurbarán dying in poverty, but at his death the value of his estate was about 20,000 reales.[10]

Style

It is unknown whether Zurbarán had the opportunity to see the paintings of Caravaggio, only that his work features a similarly realistic use of chiaroscuro and tenebrism. The painter thought by some art historians to have had the greatest influence on his characteristically severe compositions was Juan Sánchez Cotán.[11] Polychrome sculpture—which by the time of Zurbarán's apprenticeship had reached a level of sophistication in Seville that surpassed that of the local painters—provided another important stylistic model for the young artist; the work of Juan Martínez Montañés is especially close to Zurbarán's in spirit.[11]

He painted his figures directly from nature, and he made great use of the lay-figure in the study of draperies, in which he was particularly proficient. He had a special gift for white draperies; as a consequence, the houses of the white-robed Carthusians are abundant in his paintings. To these rigid methods, Zurbarán is said to have adhered throughout his career, which was prosperous, wholly confined to Spain, and varied by few incidents beyond those of his daily labour. His subjects were mostly severe and ascetic religious vigils, the spirit chastising the flesh into subjection, the compositions often reduced to a single figure. The style is more reserved and chastened than Caravaggio's, the tone of color often quite bluish. Exceptional effects are attained by the precisely finished foregrounds, massed out largely in light and shade. Backgrounds are often featureless and dark. Zurbaran had difficulty painting deep space; when interior or exterior settings are represented, the effect is suggestive of theater backdrops on a shallow stage.[12]

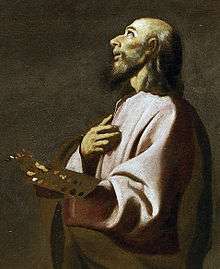

Zurbaran's late works, such as the Saint Francis (c. 1658–1664; Alte Pinakothek) show the influence of Murillo and Titian in their looser brushwork and softer contrasts.[13]

Artistic legacy

In 1631 he painted the great altarpiece of the Apothosis of St. Thomas Aquinas, now in the Museum of Fine Arts of Seville; it was executed for the church of the college of that saint.[14] This is Zurbarán's largest composition,[15] containing figures of Christ, the Madonna, various saints, Charles V with knights, and Archbishop Deza (founder of the college) with monks and servitors, all the principal personages being more than life-size. It had been preceded by numerous pictures for the retable of St. Peter in the cathedral of Seville.[16]

Between 1628 and 1634 he painted four scenes from the life of St. Peter Nolasco for the Principal Monastery of the Calced Mercedarians in Seville.[17] In Santa Maria de Guadalupe he painted various large pictures, eight of which relate to the history of St. Jerome;[9] and in the church of Saint Paul, Seville, a famous figure of the Crucified Saviour, in grisaille, creating an illusion of marble. In 1639 he finished the paintings of the high altar of the Carthusians in Jerez.[18] In the palace of Buenretiro, Madrid are four large canvases representing the Labours of Hercules, the only group of mythological subjects from the hand of Zurbarán.[19] A fine example of his work is in the National Gallery, London: a whole-length, life-sized figure of a kneeling Saint Francis holding a skull.

Jacob and his twelve sons, a series depicting the patriarch Jacob and his 12 sons, is held at Auckland Castle in Bishop Auckland.[20] In 1835, paintings by Zurbarán were confiscated from monasteries and displayed in the new Museum of Cádiz.

His principal pupils were Bernabé de Ayala, Juan Caro de Tavira, and the Polanco brothers. Others included Ignacio de Ries.

Zurbarán was the subject of a major exhibition in 1987 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which traveled in 1988 to Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris. In 2015 the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid presented Zurbarán. A New Perspective.

Gallery

Saint Serapion, 1628, Wadsworth Atheneum

Saint Serapion, 1628, Wadsworth Atheneum Visión de San Pedro Nolasco, 1629, Museo del Prado

Visión de San Pedro Nolasco, 1629, Museo del Prado.jpg) Immaculate Conception, 1630, Museo del Prado

Immaculate Conception, 1630, Museo del Prado The Death of St. Bonaventure (The Body of St. Bonaventure in the Presence of Pope Gregory X and James I of Aragon), 1629–1630, Louvre Museum

The Death of St. Bonaventure (The Body of St. Bonaventure in the Presence of Pope Gregory X and James I of Aragon), 1629–1630, Louvre Museum The Young Virgin, 1630, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Young Virgin, 1630, Metropolitan Museum of Art St. Margaret as a shepherdess, 1631 National Gallery

St. Margaret as a shepherdess, 1631 National Gallery The Defense of Cadiz against the English, 1634, Museo del Prado

The Defense of Cadiz against the English, 1634, Museo del Prado A Doctor of Law, 1635, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

A Doctor of Law, 1635, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Santa Isabel de Portugal, c. 1635, Museo del Prado

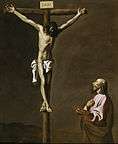

Santa Isabel de Portugal, c. 1635, Museo del Prado Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross, c. 1635–1640, Museo del Prado

Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross, c. 1635–1640, Museo del Prado The Annunciation, 1637–1639, Museum of Grenoble, France

The Annunciation, 1637–1639, Museum of Grenoble, France Saint Rufina, c. 1635–1640, Museo del Prado

Saint Rufina, c. 1635–1640, Museo del Prado Saint Francis in Meditation, 1639, National Gallery

Saint Francis in Meditation, 1639, National Gallery

Saint Francis, c. 1658–1664, Alte Pinakothek

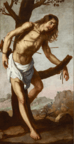

Saint Francis, c. 1658–1664, Alte Pinakothek Francisco de Zurbarán, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, MNHA Luxembourg

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, MNHA Luxembourg

Notes

- ↑ Bussagli, Marco; Reiche, Mattia (2009). Baroque & Rococo. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 95. ISBN 9781402759253.

- ↑ Pérez, Javier Portús (2004). The Spanish Portrait: From El Greco to Picasso. Museo Nacional del Prado. p. 147. ISBN 9781857593747.

- ↑ "Seventeenth-century Art and Architecture". google.com.

- 1 2 "Zurbarán, 1598-1664". google.com. p. 135.

- 1 2 Baticle, Jeannine. "Francisco de Zurbaran: A Chronological Review". In Baticle, Jeannine. Zurburan. Metropolitan Museum of Art (1987), at p. 53.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Ressort and Jordan, Grove Art Online.

- ↑ Goodwin, Robert (2015). Spain. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press. p. 474. ISBN 9781620403600.

- 1 2 Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 15.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, pp. 20, 67.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 82.

- ↑ Mallory, Nina A. (1990). El Greco to Murillo: Spanish Painting in the Golden Age, 1556-1700. Harper & Row. p. 116. ISBN 0064355314.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 74.

- ↑ Gállego and Gudiol 1987, p. 86.

- ↑ Splendor, Myth, and Vision: Nudes from the Prado: "Hercules as a Symbol of the Spanish Monarchy", The Clark Art Institute. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Zurbaran Paintings". Auckland Castle. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ "Santo Domingo en Soriano". artehistoria.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 April 2017.

References

- Gállego, Julián; Gudiol, José (1987). Zurbarán. London: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, Ltd. ISBN 0-88168-115-6

- Ressort, Claudie; Jordan, William B. "Zurbarán, de." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francisco de Zurbarán. |

- Zurbarán, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)