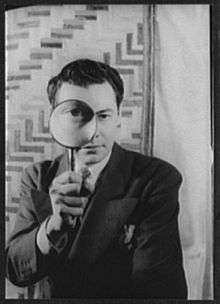

Carl Van Vechten

| Carl Van Vechten | |

|---|---|

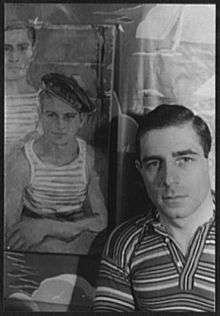

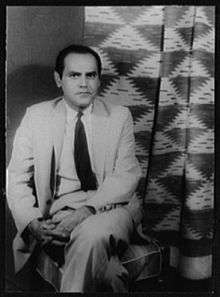

Self-portrait (1934) | |

| Born |

June 17, 1880 Cedar Rapids, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died |

December 21, 1964 (aged 84) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Education | Washington High School |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse(s) |

Anna Snyder (m. 1907–1912) |

Carl Van Vechten (June 17, 1880 – December 21, 1964) was an American writer and artistic photographer who was a patron of the Harlem Renaissance and the literary executor of Gertrude Stein.[1] He gained fame as a writer, and notoriety as well, for his novel Nigger Heaven. In his later years, he took up photography and took many portraits of notable people. Although he was married to women for most of his adult life, Van Vechten engaged in numerous homosexual affairs over his lifetime.

Life and career

Born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, he was the youngest child of Charles and Ada Van Vechten.[2]:14 Both of his parents were well educated. His father was a wealthy and prominent banker. His mother established the Cedar Rapids public library and was musically talented.[3] As a child, Van Vechten developed a passion for music and theatre.[4] He graduated from Washington High School in 1898.[5] After High School, Van Vechten was eager to take the next steps in his life, but found it difficult to pursue his passions in Iowa. He described his hometown as "that unloved town". In order to advance his education, he decided in 1899 to study at the University of Chicago.[6][4] At the University of Chicago, he studied a variety of topics including music, art and opera. As a student, he became increasingly interested in writing and wrote for the college newspaper "University of Chicago Weekly". After graduating from college in 1903, Van Vechten accepted a job as a columnist for the Chicago American. In his column "The Chaperone" Van Vechten covered many different topics through a style of semi autobiographical gossip and criticism.[4] During his time with the Chicago American, he was occasionally asked to include photographs with his column. This was the first time he was thought to have experimented with photography which would later become one of his greatest passions.[4] Van Vechten was fired from his position with the Chicago American because of what was described as an elaborate and complicated style of writing. Some described his contributions to the paper as "lowering the tone of the Hearst papers".[3] In 1906, he moved to New York City. He was hired as the assistant music critic at The New York Times.[7] His interest in opera had him take a leave of absence from the paper in 1907, so as to travel to Europe to explore opera.[1]

While in England he married his long-time friend from Cedar Rapids, Anna Snyder. He returned to his job at The New York Times in 1909, where he became the first American critic of modern dance. Under the leadership of Van Vechten's social mentor, Mabel Dodge Luhan he became engrossed in avant-garde art. This was an innovative type of art which explores new styles or subject matters and is thought to be well ahead of other art in terms of technique, subject matter and application. He also began to frequently attend groundbreaking musical premieres at the time, Isadora Duncan, Anna Pavlova, and Loie Fuller were performing in New York City. He also attended premiers in Paris where he met American author and poet Gertrude Stein in 1913 .[3] He became a devoted friend and champion of Stein. He was considered to be one of Steins most enthusiastic fans.[8] They continued corresponding for the remainder of Stein's life, and at her death she appointed Van Vechten her literary executor; he helped to bring into print her unpublished writings.[2]:306 A collection of the letters between Van Vechten and Stein has also been published.[9]

Van Vechten wrote a piece called "How to Read Gertrude Stein" for the arts magazine The Trend. In his piece Van Vechten attempted to demystify Gertrude Stein and bring clarity to her works. In his piece Van Vechten came to the conclusion that Gertrude Stein is a difficult author to understand and she can be best understood when one has been guided through her work by an "expert insider". He writes that "special writers require special readers".[10]

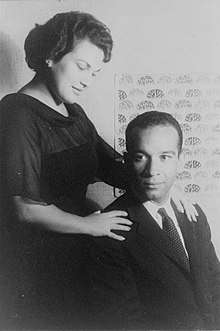

The marriage to Anna Snyder ended in divorce in 1912 and he wed actress Fania Marinoff in 1914.[11] Van Vechten and Marinoff were known for ignoring the social separation of races during the times and for inviting blacks to their home for social gatherings. They were also known to attend public gatherings for black people and even on occasion visit black friends in their homes.

Although Van Vechten's marriage to his wife Fania Marinoff, lasted for 50 years, there were often arguments between them over Van Vechten's affairs with men.[8] Van Vechten was known to have romantic and sexual relationships with men, especially Mark Lutz.[7]

Mark Lutz (1901–1968) was born in Richmond, Virginia and was introduced to Van Vechten by Hunter Stagg in New York in 1931. Lutz was a model for some of Van Vechten's earliest experiments with photography. The friendship lasted until Van Vechten's death. At Lutz's death, as per his wishes, the correspondence with Van Vechten, amounting to 10,000 letters, was destroyed. Lutz donated his collection of Van Vechten's photographs to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[12]

Several books of Van Vechten's essays on various subjects such as music and literature were published between 1915 and 1920 and Vechten would also serve as an informal scout for the newly formed Alfred A. Knopf.[13] Between 1922 and 1930 Knopf published seven novels by him, starting with Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works and ending with Parties.[14] His sexuality is most clearly reflected in his intensely homoerotic portraits of working class men.

As an appreciator of the arts, Van Vechten was extremely intrigued by the explosion of creativity which was occurring in Harlem. He was drawn towards the tolerance of Harlem society and its draw towards black writers and artists. He also felt most accepted there as a gay man.[15] Van Vechten promoted many of the major figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Ethel Waters, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston and Wallace Thurman. Van Vechten's controversial novel Nigger Heaven[6] was published in 1926. His essay "Negro Blues Singers" was published in Vanity Fair in 1926. Biographer Edward White suggests Van Vechten was convinced that Negro culture was the essence of America.[2]

Van Vechten played a critical role in the Harlem Renaissance and helped to bring greater clarity to the African American movement. However for a long time he was also seen as a very controversial figure. In Van Vechten's early writings he claimed that Black people were born to be entertainers and sexually "free". In other words he believed that black people should be free to explore their sexuality and singers should follow their natural talents such as jazz, spirituals and blues.[15]

In Harlem Van Vechten often attended opera and cabarets. He was credited for the surge in white interest in Harlem nightlife and culture. He was also involved in helping well respected writers like Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen find publishers for their first works.[16]

In 2001, Emily Bernard published "Remember Me to Harlem". This was a collection of letters which documented the long friendship between Van Vechten and Langston Hughes, who publicly defended Nigger Heaven, and enjoyed Van Vechten's mischievous sense of humor.[15] Bernard's book Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White explorers the messy and uncomfortable realities of race, and the complicated tangle of black and white in America.[15]

His older brother Ralph Van Vechten died on June 28, 1927; when Ralph's widow Fannie died in 1928, Van Vechten inherited $1 million invested in a trust fund, which was unaffected by the stock market crash of 1929 and provided financial support for Carl and Fania.[2]:242–244[17]

By the start of the 1930s and at age 50, Van Vechten was finished with writing and took up photography, using his apartment at 150 West 55th Street as a studio, where he photographed many notable persons.[18][19]

After the 1930s Van Vechten published little writing, though he continued writing letters to many correspondents.

Van Vechten died in 1964, at the age of 84, in New York City. His ashes were scattered over Shakespeare Gardens, Central Park, Manhattan, New York[20] He was the subject of a 1968 biography by Bruce Kellner, Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decades,[21] as well as Edward White's 2014 biography, The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America.[2]

Archives and museum collections

Most of Van Vechten's personal papers are held by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. The Beinecke Library also holds a collection titled "Living Portraits: Carl Van Vechten's Color Photographs Of African Americans, 1939–1964", a collection of 1,884 color Kodachrome slides.[22]

The Library of Congress has a collection of approximately 1,400 photographs, which it acquired in 1966 from Saul Mauriber (May 21, 1915 – February 12, 2003). There is also a collection of Van Vechten's photographs in the Prentiss Taylor collection in the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art, and a Van Vechten collection at Fisk University. The Museum of the City of New York's collection includes 2,174 of Carl Van Vechten's photographs. Brandeis University's department of Archives & Special Collections holds 1,689 Carl Van Vechten portraits.[23] Van Vechten also donated materials to Fisk University to form the George Gershwin Memorial Collection of Music and Musical Literature.[2]:284

In 1980, concerned that Van Vechten's fragile 35 mm nitrate negatives were fast deteriorating, photographer Richard Benson, in conjunction with the Eakins Press Foundation, transformed 50 of the portraits into handmade gravure prints. The album 'O, Write My Name': American Portraits, Harlem Heroes was completed in 1983. That year, the National Endowment for the Arts transferred the Eakins Press Foundation's prototype albums to the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[24]

The National Portrait Gallery, London holds 17 of Van Vechten's portraits of leading creative talents of his era.[25]

Works

At age 40, Van Vechten wrote the book Peter Whiffle which established him as a respected novelist. This novel was recognized as contemporary and an important work to the collection of Harlem Renaissance history. In his novel autobiographical facts were arranged into a fictional form. In addition to Peter Whiffle, Van Vechten wrote several other novels. One of them, The Tattooed Countess, was a disguised manipulation of his memories of growing up in Cedar Rapids.[8] His book the Tiger in the House explores the quirks and qualities of Van Vechtens most beloved animal, the cat.[26]

One of his most controversial novels Nigger Heaven was received with both controversy and praise. Van Vechten called this book "my Negro novel". He intended for this novel to depict how African Americans were living in Harlem and not about the suffrage of Blacks in the South who were dealing with racism and lynchings. Although many encouraged Van Vechten to reconsider giving his novel such a controversial name, he could not resist having an incendiary title. Some worried that his title would take away from the content of the book. In one letter his father wrote to him "Whatever you may be compelled to say in the book," he wrote, "your present title will not be understood & I feel certain you should change it."[27]

Many Black readers were divided over how the novel depicted African Americans. Some saw the novel as depicting Black people as "alien and strange" while others valued the novel for its representation of African Americans as everyday people, with complexity and flaws just like the average White person was. Some of the novel's supporters included Nella Larsen, Langston Hughes and Gertrude Stein. who all defended the novel for bringing Harlem society and racial issues to the forefront of America.[28]

His supporters also sent him letters to voice their opinions of the novel. Alain Locke sent Van Vechten a letter from Berlin citing his novel Nigger Heaven and the excitement surrounding its release as his primary reason for making an imminent return home. In addition Gertrude Stein sent Van Vechten a letter from France writing that the novel was the best thing he had ever written. Stein also played an important role in the development of the novel.[29]

Well known critics of this novel included African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois and Black novelist Wallace Thurman. Du Bois dismised the novel as being "cheap melodrama"[15] Decades after the book was published, literary critic and scholar Ralph Ellison remembered Van Vechten as a bad influence, an unpleasant character who "introduced a note of decadence into Afro-American literary matters which was not needed." In 1981, historian and author of a classic study of the Harlem Renaissance, David Levering Lewis, called Nigger Heaven a "colossal fraud," a seemingly uplifting book with a message that was overshadowed by "the throb of the tom-tom." He viewed Van Vechten as being driven by "a mixture of commercialism and patronizing sympathy".[27]

- Music After the Great War (1915)

- Music and Bad Manners (1916)

- Interpreters and Interpretations (1917)

- The Merry-Go-Round (1918)

- The Music of Spain (1918)

- In the Garret (1919)

- The Tiger in the House (1920)

- Lords of the Housetops (1921)

- Peter Whiffle (1922)

- The Blind Bow-Boy (1923)

- The Tattooed Countess (1924)

- Red (1925)

- Firecrackers. A Realistic Novel (1925)

- Excavations (1926)

- Nigger Heaven (1926)

- Spider Boy (1928)

- Parties (1930)

- Feathers (1930)

- Sacred and Profane Memories (1932)

Posthumous

- The Dance Writings of Carl Van Vechten (1974)

Source: A bibliography of the writings of Carl Van Vechten at the HathiTrust

Gallery

Marian Anderson, 1940

Marian Anderson, 1940 Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1958

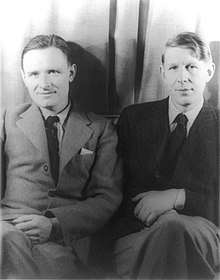

Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1958 Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden, 1939

Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden, 1939 Pierre Balmain and Ruth Ford, 1947

Pierre Balmain and Ruth Ford, 1947_-_1954_foto_Van_Vechten.jpg) Don Bachardy, 1954

Don Bachardy, 1954 Tallulah Bankhead, 1934

Tallulah Bankhead, 1934 James Baldwin, 1955

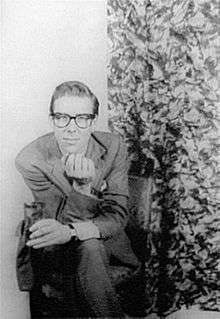

James Baldwin, 1955 Albert C. Barnes, 1940

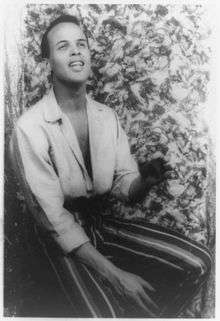

Albert C. Barnes, 1940 Harry Belafonte, 1954

Harry Belafonte, 1954 Feral Benga, 1937

Feral Benga, 1937

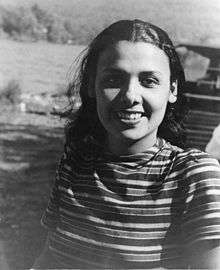

Karen von Blixen-Finecke, 1959

Karen von Blixen-Finecke, 1959 Clare Booth Luce, 1932

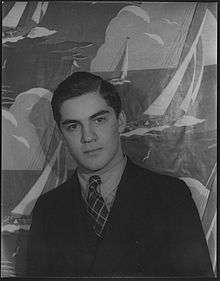

Clare Booth Luce, 1932 Marlon Brando, 1948

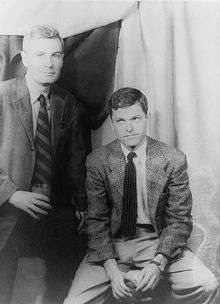

Marlon Brando, 1948 Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell, 1955

Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell, 1955 Truman Capote, 1948

Truman Capote, 1948 Katharine Cornell, 1933

Katharine Cornell, 1933.jpg) Giorgio de Chirico, 1936

Giorgio de Chirico, 1936_(LOC)_(4483943847).jpg) Salvador Dali, 1934

Salvador Dali, 1934 Gloria Davy, 1958

Gloria Davy, 1958 Mabel Dodge Luhan, 1934

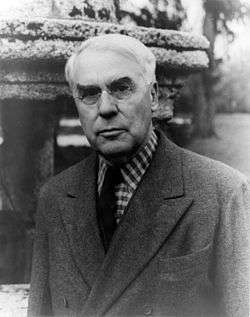

Mabel Dodge Luhan, 1934 Norman Douglas, 1935

Norman Douglas, 1935 John Van Druten, 1932

John Van Druten, 1932.jpg) John Gielgud as Richard II, 1936

John Gielgud as Richard II, 1936_(photo_by_Carl_van_Vechten).jpg) William Faulkner, 1954

William Faulkner, 1954 Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, 1952

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, 1952 Lynn Fontanne, 1932

Lynn Fontanne, 1932 Ben Gazzara, 1955

Ben Gazzara, 1955 Dizzy Gillespie, 1955

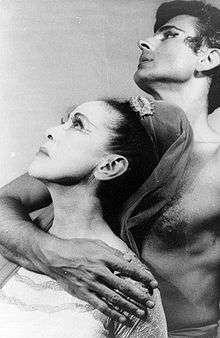

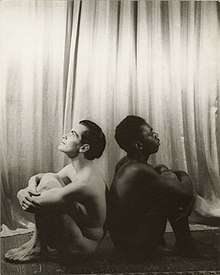

Dizzy Gillespie, 1955 Martha Graham and Bertram Ross, 1961

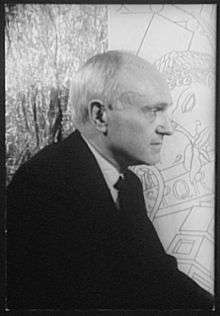

Martha Graham and Bertram Ross, 1961 Maurice Grosser, 1935

Maurice Grosser, 1935 W. C. Handy, 1941

W. C. Handy, 1941 Billie Holiday, 1949

Billie Holiday, 1949 Lena Horne, 1941

Lena Horne, 1941 Marilyn Horne and Henry Lewis, 1961

Marilyn Horne and Henry Lewis, 1961 Mahalia Jackson, 1962

Mahalia Jackson, 1962 Philip Johnson, 1933

Philip Johnson, 1933 Philip Johnson, 1963

Philip Johnson, 1963 Eartha Kitt, 1952

Eartha Kitt, 1952 Victor Kraft, 1935

Victor Kraft, 1935 Fernand Léger, 1936

Fernand Léger, 1936 Hugh Laing (left), 1940

Hugh Laing (left), 1940 Lotte Lenya, 1962

Lotte Lenya, 1962 Joe Louis, 1941

Joe Louis, 1941 Alfred Lunt, 1932

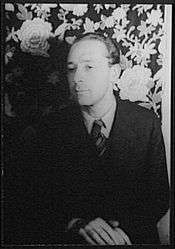

Alfred Lunt, 1932 Norman Mailer, 1948

Norman Mailer, 1948 Henri Matisse, 1933

Henri Matisse, 1933 Elsa Maxwell, 1935

Elsa Maxwell, 1935 Gian Carlo Menotti, 1944

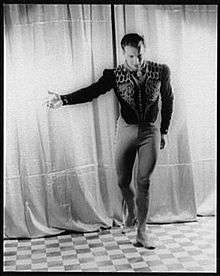

Gian Carlo Menotti, 1944 Francisco Moncion, 1947

Francisco Moncion, 1947 Robert Morse, 1958

Robert Morse, 1958 Laurence Olivier, 1939

Laurence Olivier, 1939 Christopher Plummer, 1959

Christopher Plummer, 1959 José Quintero, 1958

José Quintero, 1958 Cesar Romero, 1934

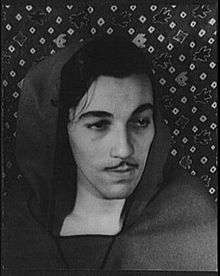

Cesar Romero, 1934 Arthur Schwartz, 1933

Arthur Schwartz, 1933 Bessie Smith, 1936

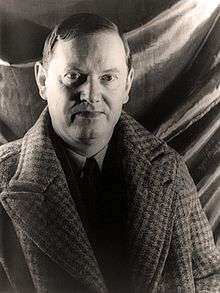

Bessie Smith, 1936 W. Somerset Maugham, 1934

W. Somerset Maugham, 1934 Gertrude Stein, 1935

Gertrude Stein, 1935 James Stewart, 1934

James Stewart, 1934 Paul Taylor, 1960

Paul Taylor, 1960 Pavel Tchelitchew, 1934

Pavel Tchelitchew, 1934 Virgil Thomson, 1947

Virgil Thomson, 1947 Antony Tudor, 1941

Antony Tudor, 1941 Gore Vidal, 1948

Gore Vidal, 1948 Hugh Walpole, 1934

Hugh Walpole, 1934 Ethel Waters, 1938

Ethel Waters, 1938 Evelyn Waugh, 1940

Evelyn Waugh, 1940 Orson Welles, 1937

Orson Welles, 1937 Anna May Wong, 1939

Anna May Wong, 1939 George Zoritch, 1942

George Zoritch, 1942

References

Notes

- 1 2 "Portraits by Carl Van Vechten – Carl Van Vechten Biography – (American Memory from the Library of Congress)". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White, Edward (2014), The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-20157-9

- 1 2 3 "Van Vechten, Carl – The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa -The University of Iowa". uipress.lib.uiowa.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Van Vechten Collection - Carl Van Vechten Biography and Chronology". www.loc.gov. 1932. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Carl Van Vechten's Camera Documented Personalities". Cedar Rapids Gazette. March 10, 1971. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- 1 2 "Carl Van Vechten Biography". Biography.com. December 21, 1964. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- 1 2 Sanneh, Kelefa (February 17, 2014). "White Mischief: The passions of Carl Van Vechten". The New Yorker.

- 1 2 3 "Van Vechten, Carl – The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa -The University of Iowa". uipress.lib.uiowa.edu. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Van Vechten Collection - Carl Van Vechten Biography and Chronology". www.loc.gov. 1932. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ↑ White, Edward. The Tastemaker : Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780374201579. OCLC 846545238.

- ↑ "Carl Van Vechten's Biography on nybooks.com". Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ↑ The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Carl Van Vechten, 1913–1946. Columbia University Press. 2013. p. 310. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ↑ Claridge, Laura (2016). The lady with the Borzoi : Blanche Knopf, literary tastemaker extraordinaire (First ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 41. ISBN 9780374114251. OCLC 908176194.

- ↑ "Carl Van Vechten Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Carl Van Vechten". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bernard, Emily (2012). Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance : a portrait in black and white. New Haven [Conn.]: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300183290. OCLC 784957824.

- ↑ Van Vechten, Carl (2006). The tiger in the house. New York: New York Review Books. ISBN 9781590172230. OCLC 76142159.

- ↑ Smalls, James (2006), The Homoerotic Photography of Carl Van Vechten: Public Face, Private Thoughts, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, p. 24, ISBN 1-59213-305-3

- ↑ "Carl Van Vechten: Biography from". Answers.com. December 21, 1964. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Prints & Photographs Online Catalog – Van Vechten Collection – Biography". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 48447). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition

- ↑ Kellner, B., Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decades (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968). OCLC 292311

- ↑ Living Portraits: Carl Van Vechten's Color Photographs Of African Americans, 1939–196. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Carl Van Vechten photographs". Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department. Brandeis University. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Harlem Heroes: Photographs by Carl Van Vechten". Exhibitions - Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp08032/carl-van-vechten

- ↑ Van Vechten, Carl (2006). The tiger in the house. New York: New York Review Books. ISBN 9781590172230. OCLC 76142159.

- 1 2 "White Mischief". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ↑ White, Edward. The Tastemaker : Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780374201579. OCLC 846545238.

- ↑ White, Edward. The Tastemaker : Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780374201579. OCLC 846545238.

Bibliography

- Bird, Rudolph P. (ed.) (1997). Generations in Black and White: Photographs of Carl Van Vechten from the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection, University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820319449

- Kellner, Bruce (1968). Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decades. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0808-8

- Kellner, Bruce (ed.) (1980). A Bibliography of the Work of Carl Van Vechten. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-20767-4

- Kellner, Bruce (ed.) (1987). Letters of Carl Van Vechten. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03907-7

- Smalls, James (2006). The Homoerotic Photography of Carl Van Vechten: Public Face, Private Thoughts. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-305-3

- White, Edward (2014). The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-20157-9

- Hurston, Zora Neale (1984). Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01047-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Van Vechten. |

- Works by Carl Van Vechten at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl Van Vechten at Internet Archive

- Works by Carl Van Vechten at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Images by Carl Van Vechten in the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York

- Creative Americans: Portraits by Carl Van Vechten at the Library of Congress features a searchable database of photographs taken by Van Vechten.

- Carl Van Vechten's Portraits from the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University features a searchable database of over 9,000 black-and-white prints

- Carl Van Vechten photographs, 1932–1964 at Brandeis University's Archives & Special Collections, contains 1,689 Van Vechten portraits.

- Living Portraits: Carl Van Vechten's Color Photographs of African Americans, 1939–1964, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, features a searchable database of 1,884 rare color Kodachrome slides

- Extravagant Crowd: Carl Van Vechten's Portraits of Women, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Postcards from Manhattan: The Portrait Photography of Carl Van Vechten at Marquette University reproduces hundreds of portrait postcards sent by Van Vechten to Wisconsin artist Karl Priebe from 1946–1956.

- Guide to the Carl Van Vechten papers, 1833–1965. Manuscripts and Archives, New York Public Library.

- Carl Van Vechten collection of papers, 1911–1964. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library.

- Carl Van Vechten theatre photographs, 1932–1943, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Booknotes interview with Emily Bernard on Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, 1925–1964, April 22, 2001.