Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria

| Rudolf | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Prince of Austria; Prince Royal of Hungary and Bohemia | |||||

| |||||

| Born |

21 August 1858 Laxenburg, Austrian Empire | ||||

| Died |

30 January 1889 (aged 30) Mayerling, Austria-Hungary | ||||

| Burial | Imperial Crypt, Vienna | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Archduchess Elisabeth Marie | ||||

| |||||

| House | Habsburg | ||||

| Father | Franz Joseph I of Austria | ||||

| Mother | Elisabeth of Bavaria | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Austrian Royalty |

| House of Habsburg-Lorraine |

|---|

.svg.png) |

| Francis I (Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor) |

|

| Ferdinand I |

| Franz Joseph I |

|

| Charles I |

|

Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria (Rudolf Franz Karl Joseph; 21 August 1858 – 30 January 1889) was the only son of Emperor Franz Joseph I and Elisabeth of Bavaria. He was heir apparent to the throne of Austria-Hungary from birth. In 1889, he died in a suicide pact with his mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, at the Mayerling hunting lodge.[1] The ensuing scandal made international headlines. He was named after the first Habsburg King of Germany, Rudolf I, who assumed the throne in 1273.[2]

Background

Rudolf was born at Schloss Laxenburg,[3] a castle near Vienna, as the son of Emperor Franz Joseph I and Empress Elisabeth. Influenced by his tutor Ferdinand von Hochstetter (who later became the first superintendent of the Imperial Natural History Museum), Rudolf became very interested in natural sciences, starting a mineral collection at an early age.[3] After his death, large portions of his mineral collection came into the possession of the University for Agriculture in Vienna.[3]

In 1877 the Count of Bombelles was master of the young prince. Bombelles was the former custodian of his aunt Empress Charlotte of Mexico.[4]

Rudolf was raised together with his older sister Gisela and the two were very close. At the age of six, Rudolf was separated from his sister as he began his education to become a future emperor. This did not change their relationship and Gisela remained close to him until she left Vienna upon her marriage to Prince Leopold of Bavaria.

In contrast with his deeply conservative father, Rudolf held liberal views, that were closer to those of his mother.[5] Nevertheless, his relationship with her was, at times, strained.[5]

Marriage

In Vienna, on 10 May 1881, Rudolf married Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, a daughter of King Leopold II of the Belgians, at the Augustinian's Church in Vienna. Although their marriage was initially a happy one, by the time their only child, the Archduchess Elisabeth, was born on 2 September 1883, the couple had drifted apart, and he found solace in drink and other female companionship. Rudolf started having many affairs, and wanted to write to Pope Leo XIII about the possibility of annulling his marriage to Stéphanie, but the Emperor forbade it.[5] Stephanie was unable to have other children due to being infected with syphilis by Rudolf.

Affairs and suicide

In 1886, Rudolf bought Mayerling, a hunting lodge.[6] In late 1888, the 30-year-old crown prince met the 17-year-old Baroness Marie Vetsera, known by the more fashionable Anglophile name Mary, and began an affair with her.[7] On 30 January 1889, he and Vetsera were discovered dead in the lodge as a result of an apparent murder–suicide. As suicide would prevent him from being given a church burial, Rudolf was officially declared to have been in a state of "mental unbalance", and he was buried in the Imperial Crypt (Kapuzinergruft) of the Capuchin Church in Vienna. Mary's body was smuggled out of Mayerling in the middle of the night and secretly buried in the village cemetery at Heiligenkreuz.[6][8] The Emperor had Mayerling converted into a penitential convent of Carmelite nuns. Prayers are still said daily by the nuns for the repose of Rudolf's soul.

The current Archduke Rudolf, son of Archduke Carl Ludwig of Austria (1918–2007), has disputed this version of events, asserting that Rudolf was in fact assassinated by Freemasons.[9]

However, Vetsera's private letters were discovered in a safe deposit box in an Austrian bank in 2015, and they revealed that she was preparing to commit suicide alongside Rudolf, out of "love".[10]

Effect of Rudolf's death

Rudolf's death plunged his mother into despair. She wore black or pearl grey, the colours of mourning, for the rest of her life and spent more and more time away from the imperial court in Vienna. Empress Elisabeth was murdered while abroad in Geneva, Switzerland in 1898 by an Italian anarchist, Luigi Lucheni.[11]

Politically, Rudolf's death left Franz Joseph without a direct male heir. Franz-Joseph's younger brother, Archduke Karl Ludwig, was next in line to the Austro-Hungarian throne,[12] though it was falsely reported that he had renounced his succession rights.[13] In any case, his death in 1896 from typhoid made his eldest son, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the new heir presumptive. In 1914, Franz Ferdinand's assassination precipitated World War I. Emperor Franz-Joseph died in November 1916 and was succeeded by his grandnephew, Karl. The demands of American President Wilson forced Emperor Karl to renounce involvement in state affairs in Vienna in early November 1918. As a result the empire ceased to exists and a republic came into being without revolution. Karl and his family went into exile in Switzerland after spending a short time at Castle Eckarstau.

In popular culture

- Mayerling, a film directed by Anatole Litvak, with Charles Boyer and Danielle Darrieux, based on a novel by Claude Anet.

- Sarajevo (1940), a film directed Max Ophüls starts with Rudolf's death.

- The musical Marinka (1945), with book by George Marion Jr., and Karl Farkas, lyrics by George Marion, Jr., music by Emmerich Kalman.

- Rudolf appears in the Austrian film Der Engel mit der Posaune (1948) and in the British remake of that film, The Angel with the Trumpet (1950).

- Mayerling, a 1968 film, starring Omar Sharif as Crown Prince Rudolf, Catherine Deneuve as Mary with James Mason as Kaiser Franz Josef and Ava Gardner as Empress Elisabeth.

- Japanese Takarazuka Revue's "Utakata no Koi"/"Ephemeral Love", based on the 1968 film.

- Requiem for a Crown Prince, one-hour episode of the British documentary/drama series Fall of Eagles (1974), directed by James Furman and written by David Turner, tracks in detail the events of 30 January 1889 and the following few days at Mayerling.

- Miklós Jancsó's 1975 film Vizi Privati, Publiche Virtù (Private Vices, Public Virtues), a reinterpretation in which the lovers and their friends are murdered by imperial authorities for treason and immorality.

- Kenneth MacMillan's 1978 ballet, Mayerling.

- Rudolf appears as a character in the musical Elisabeth (1992)

- Rudolf appears as a character in Lillie, played by Patrick Ryecart, Granada TV's dramatisation of the life of Lillie Langtry.

- Japanese manga by Higuri You, "Tenshi no Hitsugi" (Angel's Coffin) (2000).

- The Crown Prince, film directed by Robert Dornhelm (2006) in two parts.

- Composer Frank Wildhorn's musical Rudolf - Affaire Mayerling (2006), produced in some territories as The Last Kiss or Rudolf - The Last Kiss.

- The play Rudolf (2011) by David Logan dramatises the last few weeks of the life of Crown Prince Rudolf.[14]

- A highly fictionalized version of the incident at Mayerling is depicted in the 2006 film The Illusionist. The Crown Prince's name is Leopold in this telling.

Titles, styles and honours

Titles and styles

- 21 August 1858 – 30 January 1889: His Imperial and Royal Highness The Crown Prince of Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia[15]

Honours

- Domestic[16]

- Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece - 1858[17]

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen of Hungary - 1877[18]

- Foreign[16]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle

- Grand Commander of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called

- Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky

- Knight of the Order of the White Eagle

- Knight 1st Class of the Order of St. Anna

- Knight 1st Class of the Order of St. Stanislaus

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the White Elephant

- Order of the Crown of Siam

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Order of the Garter - 20 June 1887[22]

- Gold Medal Commemorating the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

Ancestors

Gallery

Crown Prince Rudolf during his early adulthood, c. 1879.

Crown Prince Rudolf during his early adulthood, c. 1879. Official engagement photo of Crown Prince Rudolf and Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, 1881.

Official engagement photo of Crown Prince Rudolf and Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, 1881. Painting "Allegory on the betrothal of Crown Prince Rudolf and Stephanie of Belgium" by Sophia and Marie Görlich, dated 1881.

Painting "Allegory on the betrothal of Crown Prince Rudolf and Stephanie of Belgium" by Sophia and Marie Görlich, dated 1881. Mayerling Lodge as it appeared before Crown Prince Rudolf's death there in 1889.

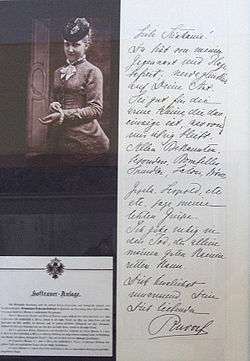

Mayerling Lodge as it appeared before Crown Prince Rudolf's death there in 1889. Crown Prince Rudolf's letter of farewell to his wife.

Crown Prince Rudolf's letter of farewell to his wife. Crown Prince Rudolf placed in a bed for private viewing by his family at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna. His head had to be bandaged in order to cover gunshot wounds. When he later lay-in-state, his skull was reconstructed using wax so that his appearance was normal.

Crown Prince Rudolf placed in a bed for private viewing by his family at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna. His head had to be bandaged in order to cover gunshot wounds. When he later lay-in-state, his skull was reconstructed using wax so that his appearance was normal.- Crown Prince Rudolf's coffin lies to the right of his parents' coffins in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna.

Statue in memory of Crown Prince Rudolf in the City Park of Budapest.

Statue in memory of Crown Prince Rudolf in the City Park of Budapest.

See also

Notes

- ↑ As documented in several autograph letters by the two unfortunate lovers ANSA newsbrief (in Italian)

- ↑ Timothy Snyder (2008) 'The Red Prince, p.9. ISBN 978-0-465-00237-5

- 1 2 3 "Crown Prince Rudolf (1858–1889)" (museum notes), Natural History Museum of Vienna, 2006, NHM-Wien-Rudolfe.

- ↑ http://www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_B/Bombelles_Karl-Albert_1832_1889.xml

- 1 2 3 "Young Wilhelm". Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 Schmöckel, Sonja. "CSI Mayerling – How did the crown prince really die?". The World of the Habsburgs. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Louise of Coburg, My Own Affairs, George H. Doran Co., 1921, p.120

- ↑ Butkuviene, Gerda (March 11, 2012). "Book Review: Myths of Mayerling". The Vienna Review. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ "A Lecture with HI & RH Archduke Rudolf of Austria". YouTube. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

From an event in 2013. In the Q&A session at 1:11:38–1:13:54, Archduke Rudolf relates the following story:

‘Basically most of the — most recent historians changed their minds now — especially in France, it's quite interesting. Two things, basically, or two or three things. I asked my grandmother [Zita of Bourbon-Parma] about it, to start with. She told me that when she was very young and married, Emperor Franz Joseph liked her very much, so she went to him and asked him. And he had imposed on himself not to speak for one hundred years, that it should not be revealed. But then he told her: "One of your aunts" — I don't remember the name of that one, she told of my grandmother — "asked the same questions the day after the death of Archduke Rudolf. Go and ask her what I told her."

‘So obviously my grandmother ran to see that person. And that old aunt said, "When the Emperor told me, before the coffin was closed, when I pay my respects, I should bow over the coffin and touch the hands of the Archduke." And she said she did it. And there were nothing in — there was nothing in the gloves. And when you look at the little room in Mayerling, you can see that with a hatchet the door was opened. So if somebody has his hands cut off — and this was probably pushing on the other side — there is no way you can shoot a bullet through your brain.

‘Now the other thing is that the archives of the Vatican have opened since. And not all the documents are there; but the main reason was that Emperor Francis Joseph, ah, wanted his son to be buried, ah, on church ground. But he couldn't, because he had committed [air quotes] "officially" suicide. So the Emperor had to explain to the Pope why he wanted it. Now why was the official version suicide? It's because Rudolf had had, sadly enough, had bad frequentations, especially with the Freemasons. The Freemasons asked him, after a few years, to do two things. The first thing was to destroy the Catholic Church in the Empire; which Archduke Rudolf, who wasn't the most best person, was ready to do. And then to push aside his father; and that he did not want to do. And that, probably, sealed his death.

‘So those are the reasons why I say it. Thank you.’

- ↑ Press release Archived 31 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. from the Austrian National Library, 31 July 2015 (German)

- ↑ "European royalty Austria: Crown Prince Rudolf". Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Carl Menger's Lectures to Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria". Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Crown Prince's Successor". New York Times. 2 February 1889.

- ↑ http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/5779956

- ↑ Kaiser Joseph II. harmonische Wahlkapitulation mit allen den vorhergehenden Wahlkapitulationen der vorigen Kaiser und Könige. Since 1780 official title used for princes ("zu Ungarn, Böhmen, Dalmatien, Kroatien, Slawonien, Königlicher Erbprinz")

- 1 2 Hof- und Staats-Handbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie (1889), Genealogy pp. 1-2

- ↑ "Toison Autrichienne (Austrian Fleece) - 19th century" (in French), Chevaliers de la Toison D'or. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ↑ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Koophandel (De) 06-03-1880

- ↑ Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 472. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- ↑ Membership of the Constantinian Order Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Wm. A. Shaw, The Knights of England, Volume I (London, 1906) page 68

Further reading

- Barkeley, Richard. The Road to Mayerling: Life and Death of Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria. London: Macmillan, 1958.

- Franzel, Emil. Crown Prince Rudolph and the Mayerling Tragedy: Fact and Fiction. Vienna : V. Herold, 1974.

- Hamann, Brigitte. Kronprinz Rudolf: Ein Leben. Wien: Amalthea, 2005, ISBN 3-85002-540-3.

- Listowel, Judith Márffy-Mantuano Hare, Countess of. A Habsburg Tragedy: Crown Prince Rudolf. London: Ascent Books, 1978.

- Lonyay, Károly. Rudolph: The Tragedy of Mayerling. New York: Scribner, 1949.

- Morton, Frederic. A Nervous Splendor: Vienna 1888/1889. Penguin 1979

- Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria. Majestät, ich warne Sie... Geheime und private Schriften. Edited by Brigitte Hamann. Wien: Amalthea, 1979, ISBN 3-85002-110-6 (reprinted München: Piper, 1998, ISBN 3-492-20824-X).

- Salvendy, John T. Royal Rebel: A Psychological Portrait of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1988.

External links

- A profile of Marie Vetsera

- Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria at Find a Grave

- IMDB on various Mayerling Films

- Crown Prince Rudolfs death

- Newspaper clippings about Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

Rudolf von Habsburg-Lorraine Cadet branch of the House of Habsburg Born: 21 August 1858 Died: 30 January 1889 | ||

| Austro-Hungarian royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ferdinand Maximilian |

Heir to the Austrian throne 21 August 1858 – 30 January 1889 |

Succeeded by Karl Ludwig |