Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York

| Richard of York | |

|---|---|

|

Duke of York Prince of Wales | |

Richard in the frontispiece of the Talbot Shrewsbury Book, 1445 | |

| Born | 21 September 1411 |

| Died |

30 December 1460 (aged 49) Wakefield, Yorkshire |

| Burial |

30 July 1476 Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay |

| Spouse | Cecily Neville (m. c. 1429) |

| Issue full list... | |

| House | House of York |

| Father | Richard, Earl of Cambridge |

| Mother | Anne Mortimer |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, also named Richard Plantagenet (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), was a leading English magnate, a great-grandson of King Edward III through his father, and a great-great-great-grandson of the same king through his mother. He inherited vast estates and served in various offices of state in Ireland, France, and England, a country he ultimately governed as Lord Protector during the madness of King Henry VI.

His conflicts with Henry's wife, Margaret of Anjou, and other members of Henry's court, as well as his competing claim on the throne, were a leading factor in the political upheaval of mid-fifteenth-century England, and a major cause of the Wars of the Roses. Richard eventually attempted to take the throne, but was dissuaded, although it was agreed that he would become king on Henry's death. But within a few weeks of securing this agreement, he died in battle.

Although Richard never became king himself, he was the father of King Edward IV and King Richard III, and grandfather of King Edward V, one of the princes in the Tower. By the marriage of his granddaughter Elizabeth of York to King Henry VII, he became an ancestor to all subsequent English monarchs.

Descent

Richard of York was born on 21 September 1411,[1] the son of Richard, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, by his wife Anne de Mortimer, the daughter of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March. Anne Mortimer was the great-granddaughter of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of King Edward III (r. 1327–1377). After the death in 1425 of Anne's childless brother Edmund, the 5th Earl of March, this ancestry supplied her son Richard, of the House of York, with a claim to the English throne that was, under English law, arguably superior to that of the reigning House of Lancaster, descended from John of Gaunt, the third son of King Edward III.[2]

On his father's side, Richard had a claim to the throne in a direct male line of descent from his grandfather Edmund, 1st Duke of York (1341–1402), fourth surviving son of King Edward III and founder of the House of York. This made Richard a prince of blood and member of the ruling dynasty of England, which might have improved his position as contender or possible successor to the throne, even though his mother's descent already gave him a better claim anyway. His adoption of the surname "Plantagenet" in 1448 would serve to emphasize this point, namely his status as an agnate of the English royal family.

Richard's mother, Anne Mortimer, is said to have died giving birth to him, and his father, the Earl of Cambridge, was beheaded in 1415 for his part in the Southampton Plot against the Lancastrian King Henry V (r. 1413–1422). Although the Earl's title was forfeited, he was not attainted, and the four-year-old orphan Richard became his father's heir.[3] Richard had an only sister, Isabel of Cambridge, who became Countess of Essex upon her second marriage in 1426.

Within a few months of his father's death, Richard's childless uncle, Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, was slain at the Battle of Agincourt on 25 October 1415. After some hesitation, King Henry V allowed Richard to inherit his uncle's title and (at his majority of 21) the lands of the Duchy of York. The lesser title but (in due course) greater estates of the Earldom of March also descended to him on the death of his maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, on 18 January 1425. The reason for Henry V's hesitation was that Edmund Mortimer had been proclaimed several times, by factions rebelling against him, to have a stronger claim to the throne than Henry's father, King Henry IV. Edmund had been a disputed heir of Richard II until his deposition by Henry IV in 1399. However, during his lifetime, Mortimer remained a faithful supporter of the House of Lancaster. Richard would inherit Edmund Mortimer's titles and claim to the throne upon his death.

Richard of York already held the Mortimer (descent from the second son of Edward III) and Cambridge (male-line descent from the fourth son of Edward III) claims to the English throne; once he inherited the March estates, as well as the Earldom of Ulster, he also became the wealthiest and most powerful noble in England, second only to the king himself. The Valor Ecclesiasticus shows that York's net income from Mortimer lands alone was £3,430 (about £350,000 today) in the year 1443–44.

Childhood and upbringing

As he was an orphan, Richard's income became the property of, and was managed by, the crown. Even though many of the lands of his uncle of York had been granted for life only, or to him and his male heirs, the remaining lands, concentrated in Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire, Yorkshire, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire were considerable. The wardship of such an orphan was therefore a valuable gift of the crown, and in October 1417 this was granted to Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, with the young Richard under the guardianship of Robert Waterton. Ralph Neville had fathered an enormous family (twenty-three children, twenty of whom survived infancy, through two wives) and had many daughters needing husbands. As was his right, in 1424 he betrothed the 13-year-old Richard to his daughter Cecily Neville, then aged 9.

In October 1425, when Ralph Neville died, he bequeathed the wardship of York to his widow, Joan Beaufort. By now the wardship was even more valuable, as Richard had inherited the Mortimer estates on the death of the Earl of March. These manors were concentrated in Wales, and in the Welsh Borders around Ludlow. They also included the Earldom of Ulster, located in Ireland. In a document dated 8 August 1435, he is described as duke of York, earl of March and Ulster, and lord of Wigmore, Clare, Trim, and Connaught.[4]

Little is recorded of Richard's early life. On 19 May 1426 he was knighted at Leicester by John, Duke of Bedford, the younger brother of King Henry V; on the same day, he was formally restored to the duchy of York[5] and his other family honours,[6] thus finally securing the entirety of his inheritance. In October 1429 (or earlier) his marriage to Cecily Neville took place. On 20 January 1430, he acted as Constable of England (in the absence of Bedford) for a duel.[4] On 6 November he was present at the formal coronation of King Henry VI in Westminster Abbey. He then followed Henry to France, being present at his coronation as king of France in Notre-Dame[5] on 16 December 1431. Finally, on 12 May 1432, he came into his inheritance and was granted full control of his estates. On 22 April 1433, York was admitted to the knightly Order of the Garter. According to The Complete Peerage, "his subsequent career forms the political history of England itself".[4]

The war in France

As York reached majority, events were unfolding in France which would tie him to the events of the ongoing Hundred Years' War. In the spring of 1434, York attended a great council meeting at Westminster which attempted to conciliate the king's uncles, the dukes of Bedford and Gloucester (heads of the regency government), over disagreements regarding the conduct of the war in France.[7] Henry V's conquests in France could not be sustained forever, as England either needed to conquer more territory to ensure permanent French subordination, or to concede territory to gain a negotiated settlement. During Henry VI's minority, his Council took advantage of French weakness and the alliance with Burgundy to increase England's possessions, but following the Treaty of Arras of 1435, Burgundy ceased to recognise the English king's claim to the French throne.

In May 1436, a few months after Bedford's death, York was appointed to succeed him as commander of the English forces in France. The estates of Normandy had been dismayed at the failure of peace talks in 1435, and requested that a royal prince was sent to prosecute the war.[8] Aside from the Duke of Gloucester, York was the only royal agnate to fit such requirement,[9] and unlike the former, who was a controversial figure[10] (and was probably unwilling to leave his power base in England at that moment),[11] Richard was a new and unaffiliated player in politics, and enjoyed family ties with England's leading magnates (his wife was niece to Cardinal Henry Beaufort), factors which made him an acceptable pick for all political factions.[12] His initial term only lasted one year (1436–37), but he secured another for an extended second period lasting from 1440 to 1445. In the increasingly unstable political climate of a nation losing a century-long war, stop-gaps and political compromises set the tone for an appoitment to such an important position,[13] but by 1440 York's lineage, loyalty,[14] neutrality, and flexibility secured him a more lasting acceptance from all parties; by then, he was also familiarised with the English establishment in France.[9]

York's stays in France lasted for two periods, the first from 1436 to 1437 and the second from 1441 to 1445. He was not often involved in military affairs, and his basic policy was to delegate the basic management of the war to the generals under his command. His role in French affairs was mostly administrative and diplomatic, and though he retained command of military policy, he seldom acted as a soldier. York occupied himself with the affairs of government as a whole, and preferred to entrust the field conduct of the war mostly to his subordinates, whose military action somewhat overshadowed the duke's own. York would instead be primarily noted for his well regarded overall governance, and his attempts to deal with the problems of a declining English rule in France.[9]

Assessments of York's performance as governor of English France seem to have varied: one contemporary annonymous English chronicler described him as ineffective, whereas the also contemporary Jean de Wavrin asserted that he carried out his duties to the letter.[15] In The Complete Peerage, it is stated that "he acquired a high reputation by maintaining Normandy almost intact against French attacks".[16] In his biography of Henry VI, Bertram Wolffe calls York "reasonably competent".[13] Historian John Watts calls his military undertakings "undistinguished", but speaks positively of his overall administrative performance.[9]

Service in France, 1436–1437

York's appointment was one of a number of stop-gap measures after the death of Bedford to try to retain French possessions until the young King Henry VI could assume personal rule. The English council was reluctant to send someone with the same powers Bedford had enjoyed, and disagreements pertaining to the terms of York's indentures delayed his departure despite the dire military situation in the mainland. York would end up having his power and role limited.[17] Unlike his predecessor, York was not allowed to appoint major financial and military officials, and instead of being classified as "regent" as Bedford was before him, he got the lesser title of "lieutenant-general and governor".[18] Notable lords who accompanied York were the Earl of Suffolk and his Neville brothers-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury and Baron Fauconberg.[8] Their army numbered 4,500 men, which, added to 1,770 sent previously, fell significantly short of the 11,100 England had promised to send, a problem compounded by the fact that York and his contingent were committed to serve for only a year, less time than earlier ones.[19] A further 2,000 men sent previously under Edmund Beaufort had been redirected to the siege of Calais.[20] Disagreements over York's powers as lieutenant stalled his departure (he would blame lack of available shipping), all while the French territories were being lost. The loss of Harfleur and all Norman ports east of it forced York to disembark at Honfleur, the nearest port to Rouen still in allied hands.[19]

After many problems and delays, York finally landed on 7 June 1436.[19] This was the duke's first ever military command.[20] The fall of Paris (his original destination) led to his army being redirected to Normandy. Working with Bedford's captains, York had some success, recapturing many lost areas and holding on to the Pays de Caux, while establishing good order and justice in the Duchy of Normandy.[13] The campaigns were mainly conducted by Lord Talbot, one of the leading English captains of the day, but York also played a part in stopping and reversing French advances, recovering Fécamp, Saint-Germain, and other towns.[21] After holding a council of war on the matter, York and English forces retook Pontoise, an important strategic post between Rouen and Paris, and threatened the capital itself. York otherwise stayed at Rouen busying himself with daily administrative affairs.

The English council seemed satisfied with York's performance and wished for him to stay longer.[12] However, he was dissatisfied with the terms under which he was appointed, as he had to find much of the money to pay his troops and other expenses from his own estates.[22] His term of office was nevertheless extended beyond the original twelve months (until the arrival of his successor, the Earl of Warwick), and he did not return to England until November 1437. It was around this time that Henry VI's long regency ended: he formally assumed full power of kingship on 13 November. In spite of York's position as one of the leading nobles of the realm, he was not included in Henry VI's Council on his return.[23]

France again, 1440–1445

Henry VI turned to York again in 1440 after peace negotiations failed. He was reappointed Lieutenant of France on 2 July, this time with the same powers that the late Bedford had earlier been granted. As in 1437, York was able to count on the loyalty of Bedford's supporters, including sir John Fastolf, sir William Oldhall, and sir William ap Thomas.[14] He was promised an annual income of £20,000 to support his position.[14] Despite this, patterns of his first lieutenancy were repeated: again departing late, he would not arrive in France until June 1441, almost a year after his appointment.[9] York finally left when continued French successes and neglect from the English crown had plunged the Norman council into despair.[24] Duchess Cecily accompanied him to Normandy, and his children Edward, Edmund and Elizabeth were all born in Rouen.

Upon arriving in France, York, with an army of over 3,600 men,[25] quickly moved down the Seine towards Pontoise, where Lord Talbot was struggling to raise its siege by the French.[9] The relief of Pontoise would be the highlight of York's military career:[26] avoiding the costly siege warfare condemned by John Fastolf, he and Talbot led a brilliant campaign involving several river crossings around the Seine and Oise in a failed attempt to bring the French army to battle, chasing them almost up to the walls of Paris.[27] The contemporary chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet expressed admiration at a successful attempt by York to distract the French while English forces crossed the river, whereafter they scared the French away.[26] However, historian Thomas Basin also suggested that his withdrawal may have disrupted a scheme by Talbot to ambush and capture Charles VII of France himself at Poissy. York's army was, though, exhausted after some skirmishing and serious logistical problems,[26] forcing them to return to Rouen in August.[28] In the end, all of York's efforts were in vain, for the French took Pontoise by assault in September 1441.[27]

The loss of the last outpost in the Île-de-France[29] was a serious blow to the English; York's efforts had failed to change the balance of the war in Normandy to England's favour.[30] This was to be York's only military action during his second lieutenancy,[9] and the catastrophe may have discouraged him from further engagements.[26] He once again shifted his focus to usual matters of administration and diplomacy.[9] York made diplomatic approaches towards the nobles of France: in 1441, he received ambassadors from Britanny and Burgundy in Rouen.[26] The talks with the Burgundians led to an indefinite truce between England and Burgundy, signed by Richard, duke of York, and Isabel, duchess of Burgundy, at Dijon on 23 April 1443.[31]

.jpg)

In 1442, York continued to hold the line in Normandy, with a new English army under Lord Talbot having arrived.[32] With the French at that time focused in Gascony, military activity in Normandy was reduced; the campaigning season in was only notable by the recapture of Conches and the siege of Dieppe,[27] but also another disaster in the loss of Granville.[33] Funding the war effort was becoming an increasing issue: the government in England dithered as to whether focus on the defense of Normandy or Gascony,[34] while York, though having been paid his annuity of £20,000 in 1441–2, did not receive anything more from England until February 1444.[35]

However, in 1443 Henry VI put the newly created Duke of Somerset, John Beaufort, in charge of an army of 8,000 men, initially intended for the relief of Gascony. The threat to that region and York's careful, if reluctant conduct of the war must have prompted the English government to support a more aggressive expedition.[9] This denied York much-needed men and resources at a time when he was struggling to hold the borders of Normandy. Not only that, but the terms of Somerset's appointment could have caused York to feel that his own role as effective regent over the whole of Lancastrian France was reduced to that of governor of Normandy. The English establishment in Normandy expressed strong opposition to the measure,[36] but the delegation York sent to remonstrate against the decision was unsuccessful.[37]

Somerset's campaign itself also added to the insult: his conduct brought England to odds with the dukes of Brittany and Alençon, disrupting York's attempts (conducted during 1442–43) to involve the English in an alliance of French nobles.[9] Somerset's army achieved nothing and eventually returned to Normandy, where Somerset died in 1444. This may have been the start of the hatred that York harboured for the Beaufort family, a resentment that would later turn into civil war.

English policy now turned back to a negotiated peace (or at least a truce) with France, so the remainder of York's time in France was spent in routine administration and domestic matters. York met Margaret of Anjou, the indended bride for Henry VI, on 18 March 1445 at Pontoise.[28] York himself entered into correspondence with Charles VII for the marriage of his eldest son Edward of Rouen to a daughter of the latter,[38] though this ultimately came to nothing.

Role in politics before 1450

The political scenario in England at this point in time was dominated by a struggle for the control of the government of Henry VI, and the conduct of the ongoing Hundred Years' War in France. Tensions revolved around the dispute between Cardinal Beaufort and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. Humphrey seems to have considered the duke of York an ally, as suggested by his complaint in 1440 at the "estrangement" of York and others from the king's confidence.[39] Neither Gloucester or York enjoyed significant favour among the king. Henry VI seems to have been reluctant to employ York, who was not invited to the first royal council at the end of the regency in November 1437.[13]

There seems to be little evidence that York was associated with Gloucester in a significant way, however. Aside from his actions in France, he seems to have kept a low profile in politics until his final return in 1445. As the Duke of Gloucester and his hawkish views on the war lost favour with the king, York seems to have remained a neutral figure. He received some other minor crown appointments, and was involved, for example, in attempts to enforce order in Wales in 1437–8. He also gained a share of the wardship of the Earl of Warwick. He also spent time touring his estates;[9] he was in Ireland in 1434–35.[28] York's main actions until 1445 were otherwise directed towards English affairs in France.

York returned to England on 20 October 1445 at the end of his five-year appointment in France. He must have had reasonable expectations of reappointment. However, he had become associated with the English in Normandy who were opposed to the policy of Henry VI's Council towards France, some of whom had followed him to England (for example Sir William Oldhall and Sir Andrew Ogard). Eventually (on 24 December 1446) the lieutenancy went to Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, who had succeeded his brother John. During 1446 and 1447, York attended meetings of Henry VI's Council and of Parliament, but most of his time was spent in administration of his estates on the Welsh border. The death of the Duke of Gloucester in 1447 made York a potential heir to the throne.

York's attitude toward the Council's surrender of the French province of Maine, in return for an extension of the truce with France and a French bride for Henry, must have contributed to his appointment on 30 July 1447 as Lieutenant of Ireland. In some ways it was a logical appointment, as Richard was also Earl of Ulster and had considerable estates in Ireland, but it was also a convenient way of removing him from both England and France. His term of office was for ten years, ruling him out of consideration for any other high office during that period.

Domestic matters kept him in England until June 1449, but when he did eventually leave for Ireland, it was with Cecily (who was pregnant at the time) and an army of around 600 men. This suggests a stay of some time was envisaged. However, claiming lack of money to defend English possessions, York decided to return to England. His financial state may indeed have been problematic, since by the mid-1440s he was owed £38,666[40] by the crown, (equivalent to £28.8 million in current value)[41] and the income from his estates was declining.

York stayed in Ireland for about a year (1449–50). Upon his arrival, various Irish nobles submitted to him, somewhat replicating the outcome of when Richard II visited the island in the 14th century.[42] York tried to befriend some important groups in Irish politics (notably the O'Neill dynasty), which would help turn Ireland into a safe refuge for him when the political situation back at home became tense. His rule would also contribute to the later popularity the House of York would enjoy on Ireland.

Leader of the Opposition, 1450–1453

In 1450, the defeats and failures of the English royal government of the previous ten years boiled over into serious political unrest. In January Adam Moleyns, Lord Privy Seal and Bishop of Chichester, was lynched. In May the chief councillor of the king, William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, was murdered on his way into exile. The House of Commons demanded that the king take back many of the grants of land and money he had made to his favourites.

In June, Kent and Sussex rose in revolt. Led by Jack Cade (taking the name Mortimer), they took control of London and killed James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele, the Lord High Treasurer of England. In August, the final towns held in Normandy fell to the French and refugees flooded back to England.

On 7 September, York landed at Beaumaris, Anglesey. Evading an attempt by Henry to intercept him, and gathering followers as he went, York arrived in London on 27 September. After an inconclusive (and possibly violent) meeting with the king, York continued to recruit, both in East Anglia and the west. The violence in London was such that Somerset, back in England after the collapse of English Normandy, was put in the Tower of London for his own safety. In December Parliament elected York's chamberlain, Sir William Oldhall, as speaker.

York's public stance was that of a reformer, demanding better government and the prosecution of the traitors who had lost northern France. Judging by his later actions, there may also have been a more hidden motive – the destruction of Somerset, who was soon released from the Tower. Although granted another office, that of Justice of the Forest south of the Trent, York still lacked any real support outside Parliament and his own retainers.

In April 1451, Somerset was released from the Tower and appointed Captain of Calais. When one of York's councillors, Thomas Young, the MP for Bristol, proposed that York be recognised as heir to the throne, he was sent to the Tower and Parliament was dissolved. Henry VI was prompted into belated reforms, which went some way to restore public order and improve the royal finances. Frustrated by his lack of political power, York retired to Ludlow.

In 1452, York made another bid for power, but not to become king himself. Protesting his loyalty, he aimed to be recognised as Henry VI's heir to the throne (Henry was childless after seven years of marriage), while also trying to destroy the Duke of Somerset, who Henry may have preferred to succeed him over York, as a Beaufort descendant. Gathering men on the march from Ludlow, York headed for London to find the city gates barred against him on Henry's orders. At Dartford in Kent, with his army outnumbered, and the support of only two of the nobility (Lords Courtenay and Cobham), York was forced to come to an agreement with Henry. He was allowed to present his complaints against Somerset to the king, but was then taken to London and after two weeks of virtual house arrest, was forced to swear an oath of allegiance at St Paul's Cathedral.

Protector of the Realm, 1453–1455

By the summer of 1453, York seemed to have lost his power struggle. Henry embarked on a series of judicial tours, punishing York's tenants who had been involved in the debacle at Dartford. The Queen consort, Margaret of Anjou, was pregnant, and even if she should miscarry, the marriage of the newly ennobled Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, to Margaret Beaufort provided for an alternative line of succession. By July, York had lost both of his offices, Lieutenant of Ireland and Justice of the Forest south of the Trent.

Then, in August 1453, Henry VI suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown, perhaps brought on by the news of the defeat at the Battle of Castillon in Gascony, which finally drove English forces from France. He became completely unresponsive, unable to speak, and had to be led from room to room. The Council tried to carry on as though the king's disability would be brief, but they had to admit eventually that something had to be done. In October, invitations for a Great Council were issued, and although Somerset tried to have him excluded, York (the premier duke of the realm) was included. Somerset's fears were to prove well grounded, for in November he was committed to the Tower.

On 22 March 1454, Cardinal John Kemp, the Chancellor, died, making continued government in the King's name constitutionally impossible. Henry could not be induced to respond to any suggestion as to who might replace Kemp.[44] Despite the opposition of Margaret of Anjou, York was appointed Protector of the Realm and Chief Councillor on 27 March 1454. York's appointment of his brother-in-law, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, as Chancellor was significant. Henry's burst of activity in 1453 had seen him try to stem the violence caused by various disputes between noble families. These disputes gradually polarised around the long-standing Percy–Neville feud. Unfortunately for Henry, Somerset (and therefore the king) became identified with the Percy cause. This drove the Nevilles into the arms of York, who now for the first time had support among a section of the nobility.

Confrontation and aftermath, 1455–1456

According to the historian Robin Storey: "If Henry's insanity was a tragedy, his recovery was a national disaster."[45] When he recovered his reason in January 1455, Henry lost little time in reversing York's actions. Somerset was released and restored to favour. York was deprived of the Captaincy of Calais (which was granted to Somerset once again) and of the office of Protector. Salisbury resigned as Chancellor. York, Salisbury, and Salisbury's eldest son, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, were threatened when a Great Council was called to meet on 21 May in Leicester (away from Somerset's enemies in London). York and his Neville relations recruited in the north and probably along the Welsh border. By the time Somerset realised what was happening, there was no time to raise a large force to support the king.

Once York took his army south of Leicester, thus barring the route to the Great Council, the dispute between him and the king regarding Somerset would have to be settled by force. On 22 May, the king and Somerset arrived at St Albans with a hastily assembled and poorly equipped army of around 2,000. York, Warwick, and Salisbury were already there with a larger and better-equipped army. More importantly, at least some of their soldiers would have had experience in the frequent border skirmishes with the Kingdom of Scotland and the occasionally rebellious people of Wales.

The First Battle of St Albans that followed hardly deserves the term battle. Possibly as few as 50 men were killed, but among them were some of the prominent leaders of the Lancastrian party, such as Somerset himself, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, and Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford. York and the Nevilles had therefore succeeded in killing their enemies, while York's capture of the king gave him the chance to resume the power he had lost in 1453. It was vital to keep Henry alive, as his death would have led, not to York becoming king himself, but to the minority rule of his two-year-old son Edward of Westminster. Since York's support among the nobility was small, he would be unable to dominate a minority Council led by Margaret of Anjou.

In the custody of York, the king was returned to London with York and Salisbury riding alongside, and with Warwick bearing the royal sword in front. On 25 May, Henry received the crown from York in a clearly symbolic display of power. York made himself Constable of England and appointed Warwick Captain of Calais. York's position was enhanced when some of the nobility agreed to join his government, including Salisbury's brother William Neville, Lord Fauconberg, who had served under York in France.

For the rest of the summer, York held the king prisoner, either in Hertford castle or in London (to be enthroned in Parliament in July). When Parliament met again in November, the throne was empty, and it was reported that the king was ill again. York resumed the office of Protector; although he surrendered it when the king recovered in February 1456, it seemed that this time Henry was willing to accept that York and his supporters would play a major part in the government of the realm.

Salisbury and Warwick continued to serve as councillors, and Warwick was confirmed as Captain of Calais. In June, York himself was sent north to defend the border against a threatened invasion by James II of Scotland. However, the king once again came under the control of a dominant figure, this time one harder to replace than Suffolk or Somerset: for the rest of his reign, it would be the queen, Margaret of Anjou, who would control the king.

Uneasy peace, 1456–1459

Although Margaret of Anjou had now taken the place formerly held by Suffolk or Somerset, her position, at least at first, was not as dominant. York had his Lieutenancy of Ireland renewed, and he continued to attend meetings of the Council. However, in August 1456 the court moved to Coventry, in the heart of the queen's lands. How York was treated now depended on how powerful the queen's views were. York was regarded with suspicion on three fronts: he threatened the succession of the young Prince of Wales; he was apparently negotiating for the marriage of his eldest son Edward into the Burgundian ruling family; and as a supporter of the Nevilles, he was contributing to the major cause of disturbance in the kingdom – the Percy–Neville feud.

Here, the Nevilles lost ground. Salisbury gradually ceased to attend meetings of the council. When his brother Robert Neville, Bishop of Durham, died in 1457, the new appointment was Laurence Booth. Booth was a member of the queen's inner circle. The Percys were shown greater favour both at court and in the struggle for power on the Scottish border.

Henry's attempts at reconciliation between the factions divided by the killings at St Albans reached their climax with The Love Day on 25 March 1458. However, the lords concerned had earlier turned London into an armed camp, and the public expressions of amity seemed not to have lasted beyond the ceremony.

Civil war breaks out, 1459

In June 1459 a Great Council was summoned to meet at Coventry. York, the Nevilles and some other lords refused to appear, fearing that the armed forces that had been commanded to assemble the previous month had been summoned to arrest them. Instead, York and Salisbury recruited in their strongholds and met Warwick, who had brought with him his troops from Calais, at Worcester. Parliament was summoned to meet at Coventry in November, but without York and the Nevilles. This could only mean that they were to be accused of treason.

York and his supporters raised their armies, but they were initially dispersed throughout the country. Salisbury beat back a Lancastrian ambush at the Battle of Blore Heath on 23 September 1459, while his son Warwick evaded another army under the command of the Duke of Somerset, and afterwards they both joined their forces with York. On 11 October, York tried to move south, but was forced to head for Ludlow. On 12 October, at the Battle of Ludford Bridge, York once again faced Henry just as he had at Dartford seven years earlier. Warwick's troops from Calais refused to fight, and the rebels fled – York to Ireland, Warwick, Salisbury and York's son Edward to Calais.[46] York's wife Cecily and their two younger sons (George and Richard) were captured in Ludlow Castle and imprisoned at Coventry.

The wheel of fortune (1459–1460)

York's flight worked to his advantage. He was still Lieutenant of Ireland and attempts to replace him failed. The Parliament of Ireland backed him, providing offers of both military and financial support. Warwick's (possibly inadvertent) return to Calais also proved fortunate. His control of the English Channel meant that pro-Yorkist propaganda, emphasising loyalty to the king while decrying his wicked councillors, could be spread around southern England. Such was the Yorkists' naval dominance that Warwick was able to sail to Ireland in March 1460, meet York and return to Calais in May. Warwick's control of Calais was to prove to be influential with the wool-merchants in London.

In December 1459 York, Warwick and Salisbury suffered attainder. Their lives were forfeit, and their lands reverted to the king; their heirs would not inherit. This was the most extreme punishment a member of the nobility could suffer, and York was now in the same situation as Henry of Bolingbroke (the future King Henry IV) in 1398. Only a successful invasion of England would restore his fortune. Assuming the invasion was successful, York had three options: become Protector again, disinherit the king's son so that York would succeed, or claim the throne for himself.

On 26 June, Warwick and Salisbury landed at Sandwich. The men of Kent rose to join them. London opened its gates to the Nevilles on 2 July. They marched north into the Midlands, and on 10 July, they defeated the royal army at the Battle of Northampton (through treachery among the king's troops), and captured Henry, whom they brought back to London.

York remained in Ireland. He did not set foot in England until 9 September, and when he did, he acted as a king. Marching under the arms of his maternal great-great-grandfather Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, he displayed a banner of the Coat of Arms of England as he approached London.

A Parliament called to meet on 7 October repealed all the legislation of the Coventry parliament the previous year. On 10 October, York arrived in London and took residence in the royal palace. Entering Parliament with his sword borne upright before him, he made for the empty throne and placed his hand upon it, as if to occupy it. He may have expected the assembled peers to acclaim him as king, as they had acclaimed Henry Bolingbroke in 1399. Instead, there was silence. Thomas Bourchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury, asked whether he wished to see the king. York replied, "I know of no person in this realm the which oweth not to wait on me, rather than I of him." This high-handed reply did not impress the Lords.[47]

The next day, Richard advanced his claim to the crown by hereditary right in proper form. However, his narrow support among his peers led to failure once again. After weeks of negotiation, the best that could be achieved was the Act of Accord, by which York and his heirs were recognised as Henry's successors. However, Parliament did grant York extraordinary executive powers to protect the realm, and made him Prince of Wales (and Earl of Chester, Duke of Cornwall) and Lord Protector of England[48] on 31 October 1460.[49] With the king effectively in custody, York and Warwick were the de facto rulers of the country.

Final campaign and death

While this was happening, the Lancastrian loyalists were rallying and arming in the north of England. Faced with the threat of attack from the Percys, and with Margaret of Anjou trying to gain the support of the new king of Scotland James III, York, Salisbury and York's second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, headed north on 2 December. They arrived at York's stronghold of Sandal Castle on 21 December to find the situation bad and getting worse. Forces loyal to Henry controlled the city of York, and nearby Pontefract Castle was also in hostile hands. The Lancastrian armies were commanded by some of York's implacable enemies such as Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland and John Clifford, whose fathers had been killed at the Battle of Saint Albans, and included several northern lords who were jealous of York's and Salisbury's wealth and influence in the North.

On 30 December, York and his forces sortied from Sandal Castle. Their reasons for doing so are not clear; they were variously claimed to be a result of deception by the Lancastrian forces, or treachery by northern lords who York mistakenly believed to be his allies, or simple rashness on York's part.[50] The larger Lancastrian force destroyed York's army in the resulting Battle of Wakefield. York was killed in the battle. The precise nature of his end was variously reported; he was either unhorsed, wounded and died fighting to the death[51] or captured, given a mocking crown of bulrushes and then beheaded.[52] Edmund of Rutland was intercepted as he tried to flee and was executed, possibly by Clifford in revenge for the death of his own father at the First Battle of St Albans. Salisbury escaped, but was captured and executed the following night.

York was buried at Pontefract, but his head was put on a pike by the victorious Lancastrian armies and displayed over Micklegate Bar at York, wearing a paper crown. His remains were later moved to Church of St Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay.[53]

Legacy

Within a few weeks of Richard of York's death, his eldest surviving son was acclaimed King Edward IV and finally established the House of York on the throne following a decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton. After an occasionally tumultuous reign, he died in 1483 and was succeeded by his twelve-year-old son, Edward V, who was himself succeeded after 86 days by his uncle, York's youngest son, Richard III.

Richard of York's grandchildren included Edward V and Elizabeth of York. Elizabeth married Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, and became the mother of Henry VIII, Margaret Tudor, and Mary Tudor. All future English monarchs would come from the line of Henry VII and Elizabeth, and therefore from Richard of York himself.

In literature, Richard appears in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 1, in Henry VI, Part 2 and in Henry VI, Part 3.[54]

Richard of York is the subject of the popular mnemonic "Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain" to remember the colours of a rainbow in order (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet).

Offices

- Lieutenant-general and governor of France (8 May 1436 – 16 July 1437,[55] 2 July 1440 – 29 September 1445)[13]

- Lord Protector of the Realm of England

- Lieutenant of Ireland

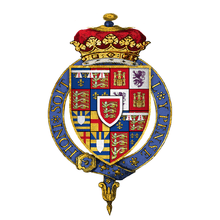

Arms

.svg.png) |

|

Ancestry

Richard was descended from English and Castilian royalty, as well as several major English aristocratic families.

| Ancestors of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Issue

His twelve children with Cecily Neville are:

- Anne of York (10 August 1439 – 14 January 1476). Married to Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter and Thomas St. Leger.

- Henry of York (10 February 1441, Hatfield – died young).

- Edward IV of England (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483). Married to Elizabeth Woodville.

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland (17 May 1443 – 30 December 1460).

- Elizabeth of York (22 April 1444 – after January 1503). Married to John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk (his first marriage, later annulled, was to Lady Margaret Beaufort when she was about 3 years old).

- Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503). Married to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

- William of York (b. 7 July 1447, died young).

- John of York (b. 7 November 1448, died young).

- George, Duke of Clarence (21 October 1449 – 18 February 1478). Married to Lady Isabel Neville. Parents of Lady Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury.

- Thomas of York (born c. 1451, died young).

- Richard III of England (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485). Married to Lady Anne Neville, the sister of Lady Isabel, Duchess of Clarence.

- Ursula of York (born 22 July 1455, died young).

Anne of York with husband Thomas St Leger

Anne of York with husband Thomas St Leger

Margaret of York

Margaret of York

Footnotes

- ↑ Richardson IV 2011, pp. 400–404.

- ↑ Dockray, Keith (2016). Henry VI, Margaret of Anjou and the Wars of the Roses: from contemporary chronicles, letters & records (revised ed.). Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1-78155-469-2.

- ↑ Harriss 2004.

- 1 2 3 Cokayne 1959, p. 906.

- 1 2 Richardson IV 2011, p. 404.

- ↑ Cokayne, G. (1912). Vicary Gibbs, ed. The Complete Peerage. 2 (2nd ed.). London: St. Catherine Press. p. 495

- ↑ Laynesmith 2017, p. 32.

- 1 2 Barker 2012, p. 235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Watts 2011.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 248.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 455; Barker 2012, pp. 235, 248.

- 1 2 Laynesmith 2017, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wolffe 2001, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Griffiths 1981, p. 459.

- ↑ Madison, Kenneth G. (1991). "Duke Richard of York, 1411–1460. P. A. Johnson". Speculum (review). 66 (3): 647–8. doi:10.2307/2864254. p. 647

- ↑ Cokayne 1959, pp. 906–7.

- ↑ Barker 2012, pp. 247–9.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 455.

- 1 2 3 Barker 2012, p. 249.

- 1 2 Griffiths 1981, p. 201.

- ↑ Turner, S. (1825). The History of England During the Middle Ages. 3 (2nd ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green. p. 28

- ↑ Rowse 1998, p. 111.

- ↑ Storey 1986, p. 72.

- ↑ Gairdner 1896, p. 177; Barker 2012, p. 289.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 290.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laynesmith 2017, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Wolffe 2001, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 Gairdner 1896, p. 177.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 292.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 294.

- ↑ Wolffe 2001, p. 169.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 462.

- ↑ Barker 2012, p. 302.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 463–4.

- ↑ Wolffe 2001, p. 154–5.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 467.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 468.

- ↑ Gairdner 1896, p. 177–8.

- ↑ Roskell 1965, p. 221.

- ↑ Keen 1973, p. 438.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ↑ Hariss 2005, p. 515.

- ↑ Doyle 1864, p. 400.

- ↑ Goodwin, George (2012-02-16). Fatal Colours. London: Phoenix. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-7538-2817-5.

- ↑ Storey 1986, p. 159.

- ↑ Goodman 1990, p. 31.

- ↑ Rowse 1998, p. 142.

- ↑ Act of Accord, from Davies, John S., An English Chronicle of the Reigns of Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI, folios 208–211 (from Googlebooks, retrieved 15 July 2013)

- ↑ Cokayne 1959, p. 908.

- ↑ Rowse 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Sadler, John (2011). Towton: The Battle of Palm Sunday Field 1461. Pen & Sword Military. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84415-965-9.

- ↑ Seward, Desmond (2007). A Brief History of the Wars of the Roses. London: Constable and Robin. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84529-006-1.

- ↑ Haigh, P. (2014-07-02) [2001-08-01]. From Wakefield to Towton (reprint ed.). Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-0-85052-825-1. pp. 31ff.

- ↑ "Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York". shakespeareandhistory.com/. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, p. 456.

- ↑ European Heraldry. War of the Roses

- ↑ Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family

- ↑ Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press, ISBN 0-900455-25-X

References

- Barker, J. (2012). Conquest: The English Kingdom of France 1417–1450 (PDF). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06560-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018.

- Cokayne, G. (1932). H.A. Doubleday; Baron Howard de Walden., eds. The Complete Peerage. 8 (2nd ed.). London: St. Catherine Press. pp. 445–53.

- Cokayne, G. (1959). G.H. White, ed. The Complete Peerage. 12.2 (2nd ed.). London: St. Catherine Press.

- Doyle, J. (1864). A Chronicle of England: B.C. 55–A.D. 1485. Illustrated by J. Doyle, engraving and colouring by Edmund Evans. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green.

- Griffiths, R.A. (2004). "Mortimer, Edmund, fifth earl of March and seventh earl of Ulster (1391–1425)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19344. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Harriss, G.L. (2004). "Richard, earl of Cambridge (1385–1415)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23502. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hariss, G.L. (2005-01-27). Shaping the Nation: England 1360–1461. New Oxford History of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822816-5.

- Keen, M. (1973). England in the Later Middle Ages. London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-416-75990-7.

- Laynesmith, J. (2017-07-13). Cecily Duchess of York. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4742-7225-4.

- Richardson, D. (2011). Kimball G. Everingham, ed. Magna Carta Ancestry. 3 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1-4499-6639-3.

- Richardson, D. (2011). Kimball G. Everingham, ed. Magna Carta Ancestry. 4 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1-4609-9270-8.

- Roskell, J. (1965). The Commons and their Speakers in English Parliaments 1376–1523. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0078-2.

- Watts, J. (2011-05-19). "Richard of York, third duke of York (1411–1460)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23503.

- Weir, A. (2008-12-18). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-953973-5.

General references

- Goodman, A. (1990-07-19) [1981]. The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–97. Routledge & Kegan. ISBN 978-0-415-05264-1.

- Griffiths, R.A. (1981). The Reign of Henry VI. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04372-5.

- Harriss, G.L. (1960-01-01). "The Struggle for Calais: An Aspect of the Rivalry between Lancaster and York". The English Historical Review. 75 (294): 30–53. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXV.294.30. JSTOR 558799. p.30

- Hicks, M. (1991-01-15). Warwick the Kingmaker. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-16259-9.

- Jacob, E.F. (1988) [1961-12-31]. The Fifteenth Century, 1399–1485. Oxford History of England. 6 (reprint ed.). Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821714-5.

- Johnson, P.A. (1988-08-25). Duke Richard of York 1411–1460. Oxford Historical Monographs. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822946-9.

- Rowse, A.L. (1998) [1966]. Bosworth Field and the Wars of the Roses (new ed.). Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 978-1-85326-691-1.

- Storey, R.L. (1986). The End of the House of Lancaster. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86299-290-3.

- Wolffe, Bertram (2001-06-10). Henry VI. Yale English Monarchs series. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08926-4.

Further reading

- Flaherty, W. (1876). The Annals of England. Oxford and London: James Parker and co.

- Haigh, P. (1997). The Battle of Wakefield. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1342-3.

- Hilliam, David (2004-06-17). Kings, Queens, Bones & Bastards (new revised ed.). The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3553-1.

- Lewis, Matthew (2016-01-05), The Fall of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, archived from the original on 9 November 2016

- Low, S.; Pulling, F., eds. (1910). "York, Richard, Duke of". The Dictionary of English History. Cassell.

- Pugh, T.B. (1986), "Richard Plantagenet (1411–60), Duke of York, as the King's Lieutenant in France and Ireland", in J.G. Rowe, Aspects of Late Medieval Government and Society, University of Toronto Press, pp. 107–42, ISBN 978-0-8020-5695-5

- Pugh, T.B. (2001). "The Estates, Finances and Regal Aspirations of Richard Plantagenet (1411–1460), Duke of York". In M. Hicks. Revolution and Consumption in Late Medieval England. The Fifteenth Century. 2. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 71–88. ISBN 978-0-85115-832-7.

- Webb, Alfred (1878). "

- Weir, A. (1996). The Wars of the Roses. First published in 1995 as Lancaster & York.

External links

- Britannica eds. (1998-07-20). "Richard, 3rd duke of York". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Lundy, Darryl (ed.). "Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York". The Peerage.

- Picture of Richard Plantagenet

- "Richard, Duke of York". Luminarium Encyclopedia.

- "Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York". Shakespeareandhistory.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- RoyaList Online interactive family tree (en)

- "The myth of "Joan of York" or "Joan Plantagenet"". Richard III Society Research blog. 2017-04-26. By a committee chaired by Joanna Laynesmith.

| Peerage of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Edward of Norwichas holder until 1415 |

Duke of York 24 February 1425 – 30 December 1460 |

Succeeded by Edward Plantagenet |

| Preceded by Edmund Mortimer |

Earl of March 18 January 1425 – 30 December 1460 | |

| Vacant Title last held by Richard of Conisburghas holder until 1415 |

Earl of Cambridge 19 May 1426 – 30 December 1460 | |

| Vacant | Prince of Wales Duke of Cornwall Earl of Chester 31 October 1460 – 30 December 1460 |

Vacant |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by Edmund Mortimer |

Earl of Ulster 18 January 1425 – 30 December 1460 |

Succeeded by Edward Plantagenet |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of Gloucester |

Justice in eyre south of the Trent 14 July 1447 – 2 July 1453 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Somerset |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of Bedford and The Duke of Gloucester as rulers for Henry VI until 1429 |

Lord Protector of England 3 April 1454 – 9 February 1455 19 November 1455 – 25 February 1456 31 October 1460 – 30 December 1460 |

Vacant |

| Preceded by The Duke of Bedford |

Lieutenant of France 8 May 1436 – c. 13 November 1437 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Warwick |

| Preceded by The Earl of Warwick |

Lieutenant of France 2 July 1440 – 29 September 1445 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Somerset |