RMS Aquitania

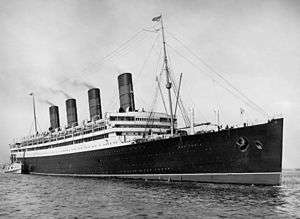

RMS Aquitania on her maiden voyage in 1914 in New York Harbor | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | RMS Aquitania |

| Owner: |

|

| Operator: | Cunard Line |

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: |

Southampton-New York (1914) (1920–1939) (1945–1948) Southampton-Halifax (1948–1950) |

| Ordered: | 8 December 1910[1] |

| Builder: | John Brown & Company, Clydebank, Scotland[1] |

| Yard number: | 409[2] |

| Laid down: | December 1910 |

| Launched: | 21 April 1913[1] |

| Christened: | 21 April 1913 by the Countess of Derby |

| Acquired: | 24 May 1914 |

| Maiden voyage: | 30 May 1914[1] |

| In service: | 30 May 1914 |

| Out of service: | 1950 |

| Fate: | Scrapped at Faslane, Scotland in 1950.[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 45,647 GRT[3] |

| Length: | 901 ft (274.6 m)[3] |

| Beam: | 97 ft (29.6 m)[3] |

| Draught: | 36 ft (11.0 m)[1] |

| Decks: | 10 |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Four shafts[3] |

| Speed: |

|

| Capacity: | |

| Crew: | 972[1] |

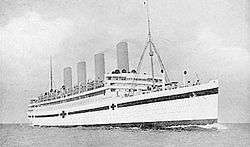

RMS Aquitania was a British ocean liner of Cunard Line in service from 1914 to 1950. She was designed by Leonard Peskett and built by John Brown & Company in Clydebank, Scotland. She was launched on 21 April 1913[4] and sailed on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York on 30 May 1914. Aquitania was the third in Cunard Line's grand trio of express liners, preceded by RMS Mauretania and RMS Lusitania, and was the last surviving four-funnelled ocean liner.[5] Shortly after entering service, World War I broke out, during which she was first transformed into an auxiliary cruiser before being transformed into a troop transport and a hospital ship, notably as part of the Dardanelles Campaign.

Returned to transatlantic passenger service in 1920, she served alongside the Mauretania and the Berengaria. Widely considered during this period of time as one of the most attractive ships, Aquitania earned the nickname "the Ship Beautiful" from her passengers.[3] Her popularity allowed her service to be continued after the merger of Cunard Line with White Star Line in 1934. The company planned to retire her and replace her with RMS Queen Elizabeth in 1940.

However, the outbreak of World War II allowed her to remain in service for ten more years. During the war and until 1947, she served as a troop transport. She was used in particular to bring home Canadian soldiers from Europe. After the war, she transported migrants to Canada before the Board of Trade found her unfit for further commercial service. Aquitania was retired from service in 1949 and was scrapped the following year. Having served as a passenger ship for 36 years, Aquitania's record for the longest service career of any 20th-century express liner stood until 2004 when Queen Elizabeth 2 became the longest serving Cunard vessel.

Conception

The origins of Aquitania lay in the rivalry between the White Star Line and Cunard Line, Britain's two leading shipping companies. The White Star Line's Olympic, Titanic and the upcoming Britannic were larger than the latest Cunard ships, Mauretania and Lusitania, by 15,000 gross tons. The Cunard duo were significantly faster than the White Star ships, while White Star's ships were seen as more luxurious. Cunard needed another liner for its weekly transatlantic express service, and elected to copy the White Star Line's Olympic-class model with a larger, slower, but more luxurious ship.[3][6][7] The plan for the building of that liner began in 1910. Several draft plans were conceived in order to determine the main axes of what should be the ship for which an average speed of 23 knots was planned. In July of that year, the company launched the construction offers to several shipyards before choosing John Brown and Company, the builder of the Lusitania. The company chose Aquitania as the name for its new ship in continuity with those of its two previous duo. The three ships were named respectively after the Ancient Roman provinces Lusitania, Mauretania, and Gallia Aquitania.[8]

Design, construction and launch

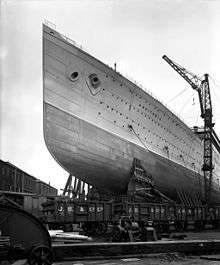

Aquitania was designed by Cunard naval architect Leonard Peskett.[3] Peskett drew up plans for a larger and wider vessel than Lusitania and Mauretania (about 40 meters longer). With four large funnels the ship would resemble the famous speed duo, but Peskett also designed the superstructure with "glassed in" touches from the smaller Carmania, a ship he also designed. Another design feature from Carmania was the addition of two tall forward deck ventilator cowlings. Although the ship's tonnage remained less than that of the Olympic, her displacement was greater.[9] With Aquitania's keel being laid at the end of 1910, the experienced Peskett took a voyage on Olympic in 1911 so as to experience the feel of a ship reaching nearly 50,000 tonnes as well as to copy pointers for his company's new vessel.[9] Though Aquitania was built solely with Cunard funds, Peskett designed her according to strict British Admiralty specifications. Aquitania was built in the John Brown and Company yards in Clydebank, Scotland,[4] where the majority of the Cunard ships were built. The keel was laid in the same plot where Lusitania had been built, and would later be used to construct Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, and Queen Elizabeth 2.[10]

In the wake of the Titanic sinking, Aquitania was one of the first ships to carry enough lifeboats for all passengers and crew.[3] Eighty lifeboats, including two motorised launches with Marconi wireless equipment, were carried in both swan-neck and newer Welin type davits.[11] Watertight compartments were installed in order to allow the ship to float with five compartments flooded. She also possessed a double hull.[12] As required by the British Admiralty, she was designed to be converted into an armed merchant cruiser, and was reinforced to mount guns for service in that role. The ship displaced approximately 49,430 tons of which the hull accounted for 29,150 tons, machinery 9,000 and bunkers 6,000 tons.[13]

Aquitania was launched on 21 April 1913 after being christened by Alice Stanley, the Countess of Derby, and fitted out over the next thirteen months. Notable installations were electrical wiring and decorations. The fitting out was led by Arthur Joseph Davis and his associate Charles Mewès.[9] On 10 May 1914, she was tested in her sea trials and steamed at one full knot over the expected speed. On 14 May, she reached Mersey and stayed at a port there for fifteen days, during which she underwent a final major cleaning and finishing in preparation for her maiden voyage.[14]

Technical aspects

Aquitania was the first Cunard liner to have a length that exceeds 900 feet.[9] Unlike other liners with four funnels, Aquitania did not have a dummy funnel; every funnel was utilised in venting steam from boilers.[15] The superstructure of the ship, painted white to contrast with the black hull, was particularly imposing and the absence of a raised forecastle gave it an appearance too wide compared to the hull when seen from the front.[16]

Steam was provided by twenty-one, forced draft, double ended Scotch boilers having eight furnaces each that were 22 feet (6.7 m) long with diameter of 17 feet 8 inches (5.4 m) arranged in four boiler rooms.[17] Each boiler room had seven ash expellers with pump capacity of approximately 4,500 tons per hour that could also be used as emergency bilge pumps.[17]

Steam drove Parsons turbines in three separate engine rooms in a triple expansion system for four shafts.[17] The port engine room contained the high pressure ahead (240 tons, 40 feet 2 inches (12.2 m) long with four stage expansion) and astern turbine (120 tons, 22 feet 11 inches (7.0 m) long) for the port shaft, the center room contained two low pressure turbines with ahead and astern capability within single casings (54 feet 3 inches (16.5 m) long, nine expansion stages in ahead turbine, four in astern turbine) for the two center shafts and the starboard room contained the intermediate pressure ahead turbine (41 feet 6.5 inches (12.7 m) long) and a high pressure astern turbine (twin of the port high pressure turbine) for the starboard shaft.[17][18]

The electrical plant, located on G deck, consisted of four 400 kW British Westinghouse generator sets generating 225 volt direct current with emergency power provided by a diesel driven 30 kW generator on the promenade deck.[19] Power was provided for about 10,000 lamps and about 180 electric motors.[19]

Interior and design

In 1914, Aquitania had the capacity to carry 3,200 passengers (including 618 in first class, 614 in second class, and 1198 in third class). After a refit in 1926, the figure was reduced to 610 in first class, 950 in second class, and 640 in tourist class. Although, the original specification mentioned a capacity of 972 crew members, the ship sometimes carried around 1,100.[8]

Although Aquitania lacked the lean, yacht-like appearance of running mates Mauretania and Lusitania, the greater length and wider beam allowed for grander and more spacious public rooms. Her public spaces were designed by the British architect Arthur Joseph Davis of the interior decorating firm Mewès and Davis. This firm had overseen the construction and decoration of the Ritz Hotel in London and Davis himself had designed several banks in that city. His partner in the firm, Charles Mewès, had designed the interiors of the Paris Ritz, and had been commissioned by Albert Ballin, head of Germany's Hamburg-Amerika Line (HAPAG), to decorate the interiors of the company's new liner Amerika in 1905.[9]

In the years prior to the First World War, Mewès was charged with the decoration of HAPAG's trio of giant new ships, Imperator, Vaterland, and Bismarck, while Davis was awarded the contract for Aquitania.[9] In a curious arrangement between the rival Cunard and Hamburg-Amerika Lines, Mewès and Davis worked apart—in Germany and England respectively and exclusively—with neither partner being able to disclose details of his work to the other. Although this arrangement was almost certainly violated, Aquitania's first-class interiors were largely the work of Davis. The Louis XVI dining saloon owed much to Mewès' work on the HAPAG liners, but it is likely that having worked so closely together for many years the two designers' work had become almost interchangeable. Indeed, Davis must be given credit for the Carolean smoking room and the Palladian lounge; a faithful interpretation of the style of architect John Webb.[20]

The second class had a dining room, several lounges, a smoking room, a veranda cafe, and a gymnasium; all are unique facilities for this class on British liners. The third class had several common areas, a promenade, and three shared bathrooms.[20] The cabins offered great comfort. The first class included eight luxury suites, named after famous painters. A large number of first-class cabins had bathrooms, although not all did. The second-class cabins were larger than average, being capable of accommodating up to four people. Third-class cabins had only a small number of bunk beds, unlike those on concurrent vessels.[21]

Over her thirty-five years career, her facilities changed. Examples of this were the addition of a cinema during her refit from 1932 to 1933[22] and the reorganization of the tourist class during the 1920s for giving greater comfort to poor passengers.[23]

Early career and World War I

Aquitania's maiden voyage was under the command of Captain William Turner on 30 May 1914 with arrival in New York on 5 June.[1][13] The voyage received great attention. Fifteen days later, the German liner SS Vaterland, being the largest ship in the world at the time, was put into service. In the eye of the press, this maiden voyage was a matter of national prestige.[24] However, this event was overshadowed by the sinking of RMS Empress of Ireland in Quebec the previous day with over a thousand drowned.[25] However, no passenger canceled their voyage aboard the Aquitania, despite the strong emotion aroused by this sinking.[14] During her maiden voyage, the ship carried around 1,055 passengers, which was about a third of her total capacity. This was because a superstition pushed some people away from traveling on a ship's maiden voyage. The crossing fully satisfied the crew and the company. Average speed for the voyage, a distance of 3,181 nautical miles (5,891 km; 3,661 mi) measured from Liverpool to the Ambrose Channel lightship, was 23.1 knots (42.8 km/h; 26.6 mph),[13] taking into account a five-hour stop due to fog and the proximity of icebergs. The ship briefly managed to exceed 25 knots. Also, her coal consumption was significantly lower than that of Lusitania and Mauretania. Many passengers enjoyed the voyage. On the return trip, the success was renewed; she carried a total of 2,649 passengers, which was a record for a British liner leaving New York.[26]

Upon arrival at her home port, she underwent minor modifications, which took into account observations made during the two first crossings (this was typical for a liner after its first round trip).[26] Two more round trips took place in the second half of June and the whole of July of that year. Her architect Leonard Peskett was on board during those trips to note any defect and room for improvement. In total, 11,208 passengers traveled on the ship during her first six crossings. Her career was abruptly interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, which removed her from passenger service for six years.[27]

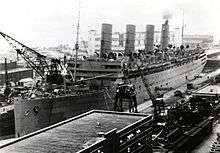

The following month Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated, and the world was plunged into World War I. Aquitania was converted into an armed merchant cruiser on 5 August 1914, for which provision had been made in her design. On 8 August, having been rid of decorative elements and armed with guns, she was sent on patrol. On 22 August, she collided with a liner named Canadian. Shortly after, the Admiralty found that large liners were too profligate in their use of fuel to act as cruisers. On 30 September, she was repaired, disarmed, and returned to Cunard Line.[28][3]

After being idle for a time, in the spring of 1915 she was recalled by the Admiralty and converted into a troopship, and made voyages to the Dardanelles, sometimes running alongside Britannic or Mauretania. Around 30,000 men were transported on the ship to the battlefield between May and August of that year.[28] Aquitania then was converted into a hospital ship, and acted in that role during the Dardanelles campaign.[1][29] In 1916, the year that White Star's flagship, and one of Aquitania's future main rivals, Britannic, was sunk, Aquitania was returned to the trooping front, and then in 1917 was laid up in the Solent.[1][30] In 1918, the ship was back on the high seas in troopship service, conveying North American troops to Britain. Many of these departures were from the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia where the ship's spectacular dazzle paint scheme was captured by artists and photographers, including Antonio Jacobsen. On one occasion Aquitania transported over 8,000 men. During her nine voyages, she transported approximately a total of 60,000 men. During this period, she collided with USS Shaw and tore apart its bow. The accident killed a dozen victims aboard the American ship.[31]

After the end of the war, in December 1918, Aquitania was dismissed from military service. She collided with the British cargo ship Lord Dufferin at New York in the United States on 28 February 1919. Lord Dufferin sank and Aquitania rescued her crew.[32] Lord Dufferin later was refloated and beached.[33]

Interwar career

In June 1919, Aquitania ran a Cunard "austerity service" between Southampton and New York. In December of that year Aquitania was docked at the Armstrong Whitworth yards in Newcastle to be refitted for post-war service. The ship was converted from coal burner to oil-fired, which greatly reduced the number of engine room crew required.[1][34] The original fittings and art pieces, removed when refitted for military use, were brought out of storage and re-installed. At some point during this time, a new wheelhouse was constructed above the original one as the officers had complained about the visibility over the ship's bow. The second wheelhouse can be seen in later pictures of the era and the old wheelhouse area below had the windows plated in.[35]

The 1920s

Aquitania resumed her commercial service on 17 July 1920, leaving from Liverpool. 2,433 passengers were on board. The crossing was a success; the ship maintained good speed while showing that the oil-fueled propulsion was much cheaper that coal-fueled propulsion.[36] The months that followed were just as promising, despite a stewards' strike in May 1921.[37] At the beginning of the decade, Aquitania was the only large liner in the service of Cunard Line as the Mauretania was undergoing repair after a fire. The year 1921 was thus an exceptional year for her; she broke a record by transporting around 60,000 passengers that year.[38] In the following year, the Mauretania rejoined her in Cunard service. Aquitania operated in service with the Mauretania and Berengaria (formerly the German liner Imperator) in a trio known as "The Big Three."[3][39]

In 1924, a new restriction on immigration was passed in the United States, causing the number of third-class passengers to drop significantly. From about 26,000 third-class passengers transported by Aquitania in 1921, the figure dropped to about 8,200 third-class passengers in 1925. The number of crew was thus reduced to around 850 people from the original 1,200.[39] The third class was no longer the key to the profitability of the liner, and so the company had to adapt. The third-class gradually became a tourist class, which offered decent service at a low price. In 1926, the ship underwent a major overhaul, which reduced the passenger capacity from around 3,300 to around 2,200.[40]

Still, the Cunard Line benefited from prohibition in the United States, which started in 1919. American liners were legally part of the territory of the United States, and thus alcoholic beverages could not be served on them. Passengers who wanted to drink therefore traveled on British liners in order to do so.[41] Aquitania enjoyed great success, making much profit for her company. In 1929, she underwent a major refit. A bathroom was added to many first-class cabins, and the tourist class was renovated. While new competitors, such as the German liner SS Bremen, entered service, Aquitania remained particularly popular after fifteen years of service.[42]

The crisis of 1929 and its consequences

Following the stock market crash of 1929, many ships were affected by the economic downturn and reduced traffic. Aquitania found herself in a tough position. Only a few could afford expensive passage on her now, so Cunard sent Aquitania on cheap cruises to the Mediterranean. These were successful, especially for Americans who went on "booze cruises," tired of their country's prohibition.[43] Another problem also arose: the two liners of the Norddeutscher Lloyd, SS Bremen and SS Europa, successfully captured the Blue Riband and many customers.[44] In 1934, the number of passengers Aquitania carried dropped to around 13,000 from 30,000 in 1929.[45] The ship, however, remained popular and she was the third busiest in the early 1930s behind those two German liners.[43]

In order to keep the ship up to date, she underwent a refit, which added a movie theater, between 1932 and 1933. At the same time, in order to modernize its fleet, the company ordered the Queen Mary. The Great Depression, however, prevented the company from being able to fully finance the construction, and the company merged with its rival, the White Star Line, in 1934 in order to do so. The Queen Mary entered service in 1936.[46] Aquitania ran aground in the Solent on 24 January 1934 but was refloated later the same day.[47] The merger of the two companies into Cunard-White Star Line resulted in a large surplus of liners being owned by a single company. Thus, very old ships, such as the Mauretania and the Olympic, were removed from service immediately and sent to the scrapyard. However, the Aquitania was not, despite her age.[48] On 10 April 1935, Aquitania went hard aground on Thorne Knoll in the Solent near Southampton, England, but with the aid of ten tugboats, on the next high tide the ship was freed.[1] When the new liner RMS Queen Elizabeth entered service in 1940, newspapers speculated that Aquitania would be scrapped that year. However, during that period, her performance continued to satisfy her company. The year 1939 saw an increase in the number of wealthy passengers on board. The ship was then already 26 years old.[49]

World War II service

Aquitania, with a normal troop capacity of 7,400, was among the select group of large, fast former passenger ships capable of sailing independently without escort transporting large numbers of troops that were assigned worldwide as needed.[50] These ships, often termed "Monsters" until London requested the term be dropped, were Aquitania, Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, Mauretania, Île de France and Nieuw Amsterdam with "lesser monsters" being other large ex-liners capable of independent sailing with large troop capacity that accounted for much of the troop capacity and deployment, particularly in the early days of the war.[51][52]

Plans to replace Aquitania with the newer Queen Elizabeth in 1940 had been forestalled by outbreak of World War II in 1939.[3] On 3 September 1939 Aquitania, awaiting initial refit as a troop ship, was at pier 90 in New York along with Queen Mary while nearby, at pier 88, were the interned French ships Île de France and Normandie.[1][3] She returned to Southampton and was requisitioned on 18 November.[53]

Aquitania's initial troop transport operation was bringing Canadian troops to England during November 1939.[1] Meanwhile, a massive transport of Australian and New Zealand troops to Suez and North Africa, with possible diversion to the United Kingdom if events required, was in planning with the numbered convoys to be designated as "US" with the large Atlantic liners assigned a role.[54] The fast convoy designated as US.3 was composed of Aquitania and the liners Queen Mary, Mauretania, Empress of Britain, Empress of Canada, Empress of Japan and Andes.[55] Aquitania, Empress of Britain and Empress of Japan, after embarking New Zealand troops at Wellington in May, sailed escorted by HMAS Canberra, HMAS Australia, and HMNZS Leander to join the Australian component off Sydney on 5 May 1940.[56] Joined off Sydney by Queen Mary and Mauretania the convoy sailed the same day to be joined the next by Empress of Canada out of Melbourne for a stop at Fremantle 10—12 May before the voyage intended to be for Colombo.[56] About midway to Colombo, on 15 May, the convoy was rerouted due to the rapid German penetrations into France with the ultimate destination of Greenock, Scotland via Cape Town, South Africa and Freetown, Sierra Leone where the escort strengthened by various ships including the aircraft carriers HMS Hermes and HMS Argus and the battlecruiser HMS Hood.[57] The convoy arrived in the Clyde and anchored off Greenock on 16 June 1940.[58]

Now repainted battleship grey, in November 1941 Aquitania was in the British colony of Singapore, from which she sailed to take part indirectly in the loss of the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney. Sydney had engaged in battle with the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran. There has been much unsubstantiated speculation that Kormoran was expecting Aquitania, after spies in Singapore had notified Kormoran's crew of the liner's sailing, and planned to ambush her in the Indian Ocean west of Perth but instead encountered Sydney on 19 November. Both ships were lost after a fierce battle. On the morning of 24 November Aquitania en route to Sydney from Singapore spotted and picked up twenty-six survivors of the German ship but maintained radio silence and did not pass word until in visual range of Wilson's Promontory on 27 November.[59] The captain had gone against orders not to stop for survivors of sinkings.[1] There were no survivors from Sydney.

December saw the outbreak of war in the Pacific, then Japanese advances throughout Southeast Asia and toward Australia, necessitating the redeployment of defensive forces.[60] On 28 December Aquitania and two smaller transports departed Sydney with 4,150 Australian troops and 10,000 tons of equipment for Port Moresby, New Guinea. (On the same date, USS Houston and other U.S. ships evacuating from the north reached Darwin, with USS Pensacola, and elements of her diverted Philippine convoy some 300 miles (480 km) ahead.) Aquitania was back in Sydney on 8 January 1942.[61] The next effort was reinforcement of Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies with Aquitania transporting Australian troops (whose equipment was in Convoy MS.1) as the single ship MS.2 convoy, under escort of HMAS Canberra.[62] The ship had been the only suitable transport for such a large movement. Originally, transport directly to Singapore was considered, but the danger from aircraft to such a valuable asset and so many troops caused a change of plans. Instead, Aquitania departed Sydney on 10 January, reaching Ratai Bay at the Sunda Strait on 20 January, where 3,456 personnel (including some Navy, Air Force and civilians) were transhipped[62] under a covering naval force to seven smaller vessels (six of them Dutch KPM ships) that would continue to Singapore as convoy MS.2A.[62] Aquitania was returned to Sydney on 31 January.[62]

With the United States in the war, Aquitania (then with a troop capacity of 4,500) had been scheduled for transport duties from the United States to Australia in February, but necessary repairs delayed that. Because her deep draft was hazardous in Australian and intermediate ports in the Pacific Islands,[63] she spent March and April 1942 transporting troops from the west coast of the U.S. to Hawaii.[51][64] Then Aquitania was temporarily transferred from Pacific duties to support the movement of troops from the United States to Britain, sailing 30 April from New York in a large convoy that transported some 19,000 troops.[65] On 12 May 1942 Aquitania loaded troops at Greenock destined for the war in the Middle East, departing in convoy WS19P on 1 June with destroyers and heavy weather, she broke off independently on 7 June due to her greater speed with designation WS19Q.[66] The first port of call was 48 hours at Freetown (West Africa) on 11 June, then 3 days at Simonstown, South Africa 20 June, 48 hours at Diego Suarez, Madagascar from 30 June, 24 hours at Steamer Point, Aden on 3 July, and then disembarkation at Port Tewfik, Egypt from 8 July 1942.[67] The return journey was via Diego Suarez, Capetown, Freetown and then to Boston. By September Aquitania was engaged in a triangular troop deployment of United States-United Kingdom-Indian Ocean voyages.[68]

As part of the major redeployment of Australian troops from North Africa to the defense of Australia and start of offensive operations in the Southwest Pacific Aquitania, Queen Mary, Île de France, Nieuw Amsterdam, and the armed merchant cruiser HMS Queen of Bermuda transported the Australian 9th Division to Sydney in Operation Pamphlet during January and February 1943.[69]

By the buildup for the invasion of Europe in 1944 troop deployments to Britain depended heavily on Aquitania and the other "Monsters" and no allowance could be made for interruption of their service for other transport requirements.[70]

Wartime embarkation at New York is described in some detail in the description of the departure of the Special Navy Advance Group 56 (SNAG 56) that was to become Navy Base Hospital Number 12 at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, England to receive casualties from Normandy. The unit was sent by "devious routes" by train to Jersey City where under cover of darkness they boarded a ferry crossing to the covered pier 86 in New York where a band played and the Red Cross served their last coffee and doughnuts as they boarded "N.Y. 40", the New York Port of Embarkation code designation for Aquitania, which got underway the morning of 29 January 1944 with some 1,000 Navy and 7,000 Army personnel for arrival at Greenock, Scotland 5 February.[71]

In eight years of military work, Aquitania sailed more than 500,000 miles, and carried nearly 400,000 soldiers,[1][72] to and from places as far afield as New Zealand, Australia, the South Pacific, Greece and the Indian Ocean.[73]

Postwar service and retirement

After completing troopship service, the vessel was handed back to Cunard-White Star in 1948. She underwent a refit for becoming suitable for passenger service. She was then used to transport war brides and their children to Canada under charter from the Canadian government. This final service created a special fondness for Aquitania in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the port of disembarkation for these immigration voyages.[74][3]

On completion of that task in December 1949, Aquitania was taken out of service when the ship's Board of Trade certificate was not renewed as the condition of the ship had reached a point of dilapidation and she was becoming too elderly and too expensive to be brought into line with new safety standards of the day, namely fire code regulations. The decks leaked in foul weather, the bulkheads and funnels were corroded to such a point that one could stick their finger through them. A piano had fallen through the roof of one of the dining rooms from the deck above during a corporate luncheon held on the ship. This truly signalled the end of Aquitania's operational life.[3][75]

The vessel was retired and sold for scrap for ₤125,000 in 1950 at Faslane in Scotland.[1] The scrapping took almost a year to complete.[75] This ended an illustrious career which included steaming 3 million miles in 450 voyages. Aquitania carried 1.2 million passengers over a career that spanned nearly 36 years, making her the longest-serving Express Liner of the 20th century. Aquitania was the only major liner to serve in both World Wars, and was the last four-funnelled passenger ship to be scrapped.[72] The ship's wheel and a detailed scale model of Aquitania may be seen in the Cunard exhibit at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

Maritime author N. R. P. Bonsor wrote of Aquitania in 1963: "Cunard had recovered possession of their veteran in 1948 but she was not worth reconditioning. In 35 years of service Aquitania had sailed more than 3 million miles and apart from one or two early Allan Line steamers no other ship served for as long in a single ownership."[76][77][78]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Pocock, Michael. "MaritimeQuest - Aquitania (1914) Builder's Data". www.maritimequest.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ↑ "HMS Aquitania". Scottish Built Ships: the history of shipbuilding in Scotland. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "TGOL - Aquitania". www.thegreatoceanliners.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- 1 2 "'Aquitania (1914 – 1950 ; 45,674 tons ; Served in two World Wars)". chriscunard.com. 2009. Retrieved 11 Jan 2009.

- ↑ The 4 funnel liners Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 37

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 33

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 13

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2009. Queen Elizabeth 2 : About QE2 : General Information. Retrieved 2 May 2009

- ↑ International Marine Engineering & (July 1914), pp. 281—282.

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 14

- 1 2 3 International Marine Engineering & (July 1914), p. 277.

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 19

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 40

- 1 2 3 4 International Marine Engineering & (July 1914), p. 282.

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, pp. 14–15

- 1 2 International Marine Engineering & (July 1914), p. 283.

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 10

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 88

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 45

- ↑ Aquitania, Down the Years, Mark Chirnside's Reception Room. Accesses 24 February 2013

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 52

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 28

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 23

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 26

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 27

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 55

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 33

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 34

- ↑ "Lord Reading's ship in collision". The Times (42038). London. 3 March 1919. col E, p. 10.

- ↑ "Casualty reports". The Times (42038). London. 3 March 1919. col A, p. 16.

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 54

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 35

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 36

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 42

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 44

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 43

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 49

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 51

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 52

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 62

- ↑ Olivier le Goff 1998, p. 73

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 91

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 64

- ↑ "Casualty reports". The Times (46661). London. 25 January 1934. col G, p. 20.

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 66

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 67

- 1 2 Leighton et al., p. 158.

- ↑ Gill 1968, pp. 36—37.

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 74

- ↑ Gill 1968, pp. 84—85, 103, 112.

- ↑ Gill 1968, p. 103.

- 1 2 Gill 1968, p. 113.

- ↑ Gill 1968, pp. 113—114.

- ↑ Gill 1968, p. 114.

- ↑ Gill 1957, p. 452.

- ↑ Gill 1957, pp. 486—512.

- ↑ Gill 1957, p. 512.

- 1 2 3 4 Gill 1957, p. 523—524.

- ↑ Leighton et al., p. 158, 203.

- ↑ Gill 1968, p. 37.

- ↑ Leighton et al., p. 362.

- ↑ "WS (Winston Specials) Convoys in WW2 - 1942 Sailings". www.naval-history.net. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ↑ Diary LAC A Richardson, 1230298

- ↑ Leighton et al., p. 364.

- ↑ Gill 1968, p. 287.

- ↑ Leighton et al., p. 298.

- ↑ Hudson 1946, pp. 7—11.

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 89

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 76

- ↑ Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 85

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside 2008, p. 86

- ↑ North Atlantic Seaway: An Illustrated History of the Passenger Services Linking the Old World with the New, with 1960 Supplement Hardcover - 1960 by N. R. P. Bonsor with later succeeding volumes updated

- ↑ British passenger liners of the five oceans, a record of the British passenger lines and their liners from 1838 to the present day(1963 when published) by Charles Robert Vernon Gibbs c.1963 LCCN Permalink https://lccn.loc.gov/63023868(Library of Congress copy) ASIN#:B000KF490M(c.1957 edition Amazon Standard Identification Number)

- ↑ Business Reference Services: Ships and Ship Registers: Sources of Information Library of Congress referral page Retrieved May 27, 2017

Bibliography

- Chirnside, Mark (2008). RMS Aquitania: The Ship Beautiful. The History Press. ISBN 9-780752-444444.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume 1. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 848228.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1968). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume 2. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 65475.

- Hudson, Henry W. (1946). The Story of SNAG 56. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,.

- "The New Cunard Express Liner Aquitania". International Marine Engineering. Aldrich Publishing Company. XIX (July 1914): 277–283. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Layton, Kent; Fitch, Tad (2016). The Unseen Aquitania: the ship in rare illustrations. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780750967358.

- Leighton, Richard M; Coakley, Robert W (1968) [1st. Pub. 1955]. The War Department — Global Logistics And Strategy 1940–1943. United States Army In World War II. 1. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060001.

- Leighton, Richard M; Coakley, Robert W (1968) [1st. Pub. 1955]. The War Department — Global Logistics And Strategy 1943–1945. United States Army In World War II. 2. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060001.

- Le Goff, Olivier (1998). Les Plus Beaux Paquebots du Monde (in French). Solar. ISBN 9782263027994.

- Navy Department—Headquarters of the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and Commander, Tenth Fleet (1945). "United States Naval Administration in World War II—History of Convoy and Routing". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aquitania (ship, 1914). |

- Aquitania Home at "Atlantic Liners.com"

- "Aquitania". Chris' Cunard Page. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- A First-Hand Account of a Second World War Voyage on the Aquitania (PDF Download)

- Maritimequest Aquitania Photo Gallery

- Aquitania on Lost Liners.com

- Cabin Liners: R.M.S. Aquitania Interior Tour

- RMS Aquitania official page on Facebook

- Aquitania Passenger List 1921 Cunard Line, List of Passengers, Southampton to New York via Cherbourg for the R.M.S. Aquitania, sailing on Saturday 25 June 1921, 32 Pages.

- Some photos of the Aquitania exhibit at the Nova Scotia Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Colorful video of the Aquitania making her final trip to the scrapyard

- Atlantic Liners: A Trio of Trios, by J. Kent Layton

- Images of RMS Aquitania at the English Heritage Archive

- Aquitania on the cover of Life magazine, July 27 1942

- Aquitania and USS Indianapolis at New York, Statue of Liberty