USS Indianapolis (CA-35)

_underway_at_sea_on_27_September_1939_(80-G-425615).jpg) USS Indianapolis (CA-35), 27 September 1939. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Indianapolis |

| Namesake: | City of Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Ordered: | 13 February 1929 |

| Awarded: | 15 August 1929 |

| Builder: | New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey |

| Cost: | $10,903,200 (contract price) |

| Laid down: | 31 March 1930 |

| Launched: | 7 November 1931 |

| Sponsored by: | Lucy M. Taggart |

| Commissioned: | 15 November 1932 |

| Identification: |

|

| Nickname(s): | "Indy"[1] |

| Honors and awards: |

|

| Fate: | Torpedoed and sunk, 30 July 1945, by Japanese submarine I-58. |

| General characteristics (as built)[2] | |

| Class and type: | Portland-class cruiser |

| Displacement: | 9,950 long tons (10,110 t) (standard) |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 66 ft 1 in (20.14 m) |

| Draft: |

|

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 32.7 kn (60.6 km/h; 37.6 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 4 × floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities: | 2 × Amidship catapults |

| General characteristics (1945)[3] | |

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 3 × floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities: | 1 × Amidship catapults (starboard catapult removed in 1945) |

USS Indianapolis (CL/CA-35) was a Portland-class heavy cruiser of the United States Navy, named for the city of Indianapolis, Indiana. The vessel served as the flagship for the commander of Scouting Force 1 for eight pre-war years, then as flagship for Admiral Raymond Spruance, in 1943 and 1944, while he commanded the Fifth Fleet in battles across the Central Pacific in World War II.

In 1945, the sinking of Indianapolis led to the greatest single loss of life at sea, from a single ship, in the history of the US Navy. The ship had just finished a high-speed trip to United States Army Air Force Base at Tinian to deliver parts of Little Boy, the first nuclear weapon ever used in combat, and was on her way to the Philippines on training duty. At 0015 on 30 July 1945 the ship was torpedoed by the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-58, and sank in 12 minutes. Of 1,195 crewmen aboard, approximately 300 went down with the ship.[4] The remaining 900 faced exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks while floating with few lifeboats and almost no food or water. The Navy learned of the sinking when survivors were spotted four days later by the crew of a PV-1 Ventura on routine patrol. Only 316 survived.[4]

On 19 August 2017, a search team financed by Paul Allen located the wreckage of the sunken cruiser in the Philippine Sea lying at a depth of approximately 18,000 ft (5,500 m).[5]

Construction

Indianapolis was the second of two ships in the Portland class; the third class of "treaty cruisers" constructed by the United States Navy following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, following the two vessels of the Pensacola class, ordered in 1926, and the six of the Northampton class, ordered in 1927.[6] Ordered for the US Navy in fiscal year 1930. Indianapolis was originally designated as a light cruiser, because of her thin armor, and given the hull classification symbol CL-35. She was reclassified a heavy cruiser, because of her 8-inch (203 mm) guns, with the symbol CA-35 on 1 July 1931, in accordance with the London Naval Treaty.[7]

As built, the Portland-class cruisers were designed for a standard displacement of 10,258 long tons (10,423 t), and a full-load displacement of 12,755 long tons (12,960 t).[8] However, when completed, she did not reach this weight, displacing 9,950 long tons (10,110 t).[9] The ship had two distinctive raked funnels, a tripod foremast, and a small tower and pole mast aft. In 1943, light tripods were added forward of the second funnel on each ship, and a prominent Naval director was installed aft.[9]

The ship had four propeller shafts and four Parsons GT geared turbines and eight White-Forster boilers. The 107,000 shp (80,000 kW) gave a design speed of 32.7 kn (60.6 km/h; 37.6 mph). She was designed for a range of 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph).[9] She rolled badly until fitted with a bilge keel.[7]

The cruiser had nine 8-inch/55 caliber Mark 9 guns in three triple mounts, a superfiring pair fore and one aft. For anti-aircraft defense, she had eight 5-inch/25 caliber guns and two QF 3 pounder Hotchkiss guns. In 1945, she received 24 40 mm (1.57 in) Bofors guns, arrayed in six quad mounts. Both ships were upgraded with 19 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon cannons.[3] No torpedo tubes were fitted on her.[10]

The Portland class originally had 1-inch (25 mm) armor for deck and side protection, but in construction[7] they were given belt armor between 5 in (127 mm) (around the magazines) and 3.25 in (83 mm) in thickness.[10] Armor on the bulkheads was between 2 in (51 mm) and 5.75 in (146 mm); that on the deck was 2.5 in (64 mm), the barbettes 1.5 in (38 mm), the gunhouses 2.5 in, and the conning tower 1.25 in (32 mm).[9]

Portland-class cruisers were outfitted as fleet flagships, with space for a flag officer and his staff. The class also had two aircraft catapult amidships.[9] They could carry four aircraft. The total crew varied, with a regular designed complement of 807,[8] a wartime complement of 952, which could increase to 1,229 when the cruiser was a fleet flagship.[9]

Indianapolis was laid down by New York Shipbuilding Corporation on 31 March 1930.[9] The hull and machinery were provided by the builder.[7] Indianapolis was launched on 7 November 1931, and commissioned on 15 November 1932.[9] She was the second ship named for Indianapolis, following the cargo ship of the same name in 1918. She was sponsored by Lucy M. Taggart, daughter of former Mayor of Indianapolis Thomas Taggart.[11]

Interwar period

_underway_in_1939.jpg)

Under Captain John M. Smeallie, Indianapolis undertook her shakedown cruise through the Atlantic and into Guantánamo Bay, until 23 February 1932. Indianapolis then transited the Panama Canal for training off the Chilean coast. After overhaul at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, she sailed to Maine, to embark President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at Campobello Island, New Brunswick, on 1 July 1933.[11] Getting under way the same day, Indianapolis arrived at Annapolis, Maryland, on 3 July. She hosted six members of the Cabinet, along with Roosevelt, during its stay there. After disembarking Roosevelt, she departed Annapolis, on 4 July, and steamed for Philadelphia Navy Yard.[12]

On 6 September, she embarked Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson, for an inspection of the Navy in the Pacific. Indianapolis toured the Canal Zone, Hawaii, and installations in San Pedro and San Diego. Swanson disembarked on 27 October. On 1 November 1933, she became flagship of Scouting Force 1, and maneuvered with the force off Long Beach, California. She departed on 9 April 1934, and arrived at New York City, and embarked Roosevelt, a second time, for a naval review. She returned to Long Beach, on 9 November 1934, for more training with the Scouting Force. She remained flagship of Scouting Force 1 until 1941. On 18 November 1936, she embarked Roosevelt, a third time, at Charleston, South Carolina, and conducted a goodwill cruise to South America with him. She visited Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Montevideo, Uruguay, for state visits before returning to Charleston, and disembarking Roosevelt's party on 15 December.[12] President Roosevelt underwent his crossing the line ceremony on this cruise on 26 November: an "intensive initiation lasting two days, but we have all survived and are now full-fledged Shellbacks".[13]

World War II

On 7 December 1941, Indianapolis was conducting a mock bombardment at Johnston Atoll, during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Indianapolis was absorbed into Task Force 12 and searched for the Japanese carriers responsible for the attack, though the force did not locate them. She returned to Pearl Harbor on 13 December, and joined Task Force 11.[12]

New Guinea campaign

With the task force, she steamed to the South Pacific, to 350 mi (560 km) south of Rabaul, New Britain, escorting the aircraft carrier Lexington. Late in the afternoon of 20 February 1942, the American ships were attacked by 18 Japanese aircraft. Of these, 16 were shot down by aircraft from Lexington and the other two were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire from the ships.[12]

On 10 March, the task force, reinforced by another force centered on the carrier Yorktown, attacked Lae and Salamaua, New Guinea, where the Japanese were marshaling amphibious forces. Attacking from the south through the Owen Stanley mountain range, the US air forces surprised and inflicted heavy damage on Japanese warships and transports, losing few aircraft. Indianapolis returned to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard for a refit before escorting a convoy to Australia.[12]

Aleutian Islands campaign

Indianapolis then headed for the North Pacific to support American units in the Battle of the Aleutian Islands. On 7 August, Indianapolis and the task force attacked Kiska Island, a Japanese staging area. Although fog hindered observation, Indianapolis and other ships fired their main guns into the bay. Floatplanes from the cruisers reported Japanese ships sunk in the harbor and damage to shore installations. After 15 minutes, Japanese shore batteries returned fire before being destroyed by the ships' main guns. Japanese submarines approaching the force were depth-charged by American destroyers. Japanese seaplanes made an ineffective bombing attack. In spite of a lack of information on the Japanese forces, the operation was considered a success. US forces later occupied Adak Island, providing a naval base farther from the Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island.

1943 operations

_underway_at_sea%2C_in_1943-1944_(NH_124466).jpg)

In January 1943, Indianapolis supported a landing and occupation on Amchitka, part of an Allied island hopping strategy in the Aleutian Islands.[12]

On the evening of 19 February, Indianapolis led two destroyers on a patrol southwest of Attu Island, searching for Japanese ships trying to reinforce Kiska and Attu. She intercepted the Japanese 3,100-long-ton (3,150 t) cargo ship, Akagane Maru laden with troops, munitions, and supplies. The cargo ship tried to reply to the radio challenge but was shelled by Indianapolis. Akagane Maru exploded and sank with all hands. Through mid-1943, Indianapolis remained near the Aleutian Islands, escorting American convoys and providing shore bombardments supporting amphibious assaults. In May, the Allies captured Attu, then turned on Kiska, thought to be the final Japanese holdout in the Aleutians. Allied landings there began on 15 August, but the Japanese had already abandoned the Aleutian Islands, unbeknownst to the Allies.[12]

After refitting at Mare Island, Indianapolis moved to Hawaii as flagship of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commanding the 5th Fleet. She sortied from Pearl Harbor on 10 November, with the main body of the Southern Attack Force for Operation Galvanic, the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. On 19 November, Indianapolis bombarded Tarawa Atoll, and next day pounded Makin (see Battle of Makin). The ship then returned to Tarawa, as fire-support for the landings. Her guns shot down an enemy plane and shelled enemy strongpoints as landing parties fought Japanese defenders in the battle of Tarawa. She continued this role until the island was secure three days later. The conquest of the Marshall Islands followed victory in the Gilberts. Indianapolis was again 5th Fleet flagship.

1944

_underway_in_1944_(stbd).jpg)

The cruiser met other ships of her task force at Tarawa, and on D-Day minus 1, 31 January 1944, she was one of the cruisers that bombarded the islands of Kwajalein Atoll. The shelling continued on D-Day, with Indianapolis suppressing two enemy shore batteries. Next day, she destroyed a blockhouse and other shore installations and supported advancing troops with a creeping barrage. The ship entered Kwajalein Lagoon, on 4 February, and remained until resistance disappeared. (See Battle of Kwajalein.)

In March and April, Indianapolis, still flagship of the 5th Fleet, attacked the Western Carolines. Carrier planes at the Palau Islands on 30–31 March, sank three destroyers, 17 freighters, five oilers and damaged 17 other ships. Airfields were bombed and surrounding water mined. Yap and Ulithi, were struck on 31 March, and Woleai, on 1 April. Japanese planes attacked but were driven off without damaging the American ships. Indianapolis shot down her second plane, a torpedo bomber, and the Japanese lost 160 planes, including 46 on the ground. These attacks prevented Japanese forces stationed in the Carolines from interfering with the US landings on New Guinea.

In June, the 5th Fleet was busy with the assault on the Mariana Islands. Raids on Saipan began with carrier-based planes on 11 June, followed by surface bombardment, in which Indianapolis had a major role, from 13 June. (See Battle of Saipan.) On D-Day, 15 June, ADM Spruance heard that battleships, carriers, cruisers, and destroyers were headed south to relieve threatened garrisons in the Marianas. Since amphibious operations at Saipan had to be protected, ADM Spruance could not withdraw too far. Consequently, a fast carrier force was sent to meet this threat while another force attacked Japanese air bases on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima, in the Bonin and Volcano Islands, bases for potential enemy air attacks.

A combined US fleet fought the Japanese on 19 June, in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Japanese carrier planes, which planned to use the airfields of Guam and Tinian, to refuel and rearm, were met by carrier planes and the guns of the Allied escorting ships. That day, the US Navy destroyed a reported 426 Japanese planes while losing 29.[14] Indianapolis shot down one torpedo plane. This day of aerial combat became known as the "Marianas Turkey Shoot". With Japanese air opposition wiped out, the US carrier planes sank Hiyō, two destroyers, and one tanker and damaged others. Two other carriers, Taihō and Shōkaku, were sunk by submarines.

Indianapolis returned to Saipan on 23 June, to resume fire support and six days later moved to Tinian, to attack shore installations (see Battle of Tinian). Meanwhile, Guam had been taken, and Indianapolis was the first ship to enter Apra Harbor, since early in the war. The ship operated in the Marianas for the next few weeks, then moved to the Western Carolines, where further landings were planned. From 12 to 29 September, she bombarded Peleliu, in the Palau Group, before and after the landings (see Battle of Peleliu). She then sailed to Manus Island, in the Admiralty Islands, where she operated for 10 days before returning to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California for refitting.

1945

Overhauled, Indianapolis joined VADM Marc A. Mitscher's fast carrier task force on 14 February 1945. Two days later, the task force launched an attack on Tokyo to cover the landings on Iwo Jima, scheduled for 19 February. This was the first carrier attack on Japan since the Doolittle Raid. The mission was to destroy Japanese air facilities and other installations in the "Home Islands". The fleet achieved complete tactical surprise by approaching the Japanese coast under cover of bad weather. The attacks were pressed home for two days. The US Navy lost 49 carrier planes while claiming 499 enemy planes, a 10:1 kill/loss ratio. The task force also sank a carrier, nine coastal ships, a destroyer, two destroyer escorts, and a cargo ship. They destroyed hangars, shops, aircraft installations, factories, and other industrial targets.

_off_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_on_10_July_1945_(19-N-86911).jpg)

Immediately after the strikes, the task force raced to the Bonin Islands, to support the landings on Iwo Jima. The ship remained there until 1 March, protecting the invasion ships and bombarding targets in support of the landings. Indianapolis returned to VADM Mitscher's task force in time to strike Tokyo, again on 25 February, and Hachijō, off the southern coast of Honshū, the following day. Although weather was extremely bad, the American force destroyed 158 planes and sank five small ships while pounding ground installations and destroying trains.

The next target for the US forces was Okinawa, in the Ryukyu Islands, which were in range of aircraft from the Japanese mainland. The fast carrier force was tasked with attacking airfields in southern Japan until they were incapable of launching effective airborne opposition to the impending invasion. The fast carrier force departed for Japan from Ulithi, on 14 March. On 18 March, it launched an attack from a position 100 mi (160 km) southeast of the island of Kyūshū. The attack targeted airfields on Kyūshū, as well as ships of the Japanese fleet in the harbors of Kobe and Kure, on southern Honshū. The Japanese located the American task force on 21 March, sending 48 planes to attack the ships. Twenty-four fighters from the task force intercepted and shot down all the Japanese aircraft.

Pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa began on 24 March. Indianapolis spent 7 days pouring 8-inch shells into the beach defenses. During this time, enemy aircraft repeatedly attacked the American ships. Indianapolis shot down six planes and damaged two others. On 31 March, the ship's lookouts spotted a Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar" fighter as it emerged from the morning twilight and roared at the bridge in a vertical dive. The ship's 20 mm guns opened fire, but within 15 seconds, the plane was over the ship. Tracers converged on it, causing it to swerve, but the enemy pilot managed to release his bomb from a height of 25 ft (7.6 m), crashing his plane into the sea near the port stern. The bomb plummeted through the deck, into the crew's mess hall, down through the berthing compartment, and through the fuel tanks before crashing through the keel and exploding in the water underneath. The concussion blew two gaping holes in the keel which flooded nearby compartments, killing nine crewmen. The ship's bulkheads prevented any progressive flooding. Indianapolis, settling slightly by the stern and listing to port, steamed to a salvage ship for emergency repairs. Here, inspection revealed that her propeller shafts were damaged, her fuel tanks ruptured, and her water-distilling equipment ruined. But Indianapolis commenced the long trip across the Pacific, under her own power, to the Mare Island Navy Yard for repairs.

Secret mission

After major repairs and an overhaul, Indianapolis received orders to proceed to Tinian island, carrying parts and the enriched uranium[15] (about half of the world's supply of Uranium-235 at the time) for the atomic bomb Little Boy, which would later be dropped on Hiroshima.[16] Indianapolis departed San Francisco's Hunters Point Naval Shipyard on 16 July 1945, within hours of the Trinity test.

Indianapolis set a speed record of 74 1⁄2 hours[17] with an average speed of 29 kn (54 km/h; 33 mph) from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, which still stands today. Arriving at Pearl Harbor on 19 July,[18] she raced on unaccompanied,[19] delivering the atomic weapon components to Tinian on 26 July.[20]

Indianapolis was then sent to Guam, where a number of the crew who had completed their tours of duty were replaced by other sailors. Leaving Guam on 28 July, she began sailing toward Leyte, where her crew was to receive training before continuing on to Okinawa, to join VADM Jesse B. Oldendorf's Task Force 95.

Sinking

At 00:15 on 30 July, she was struck on her starboard side by two Type 95 torpedoes, one in the bow and one amidships, from the Japanese submarine I-58,[19] captained by Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, who initially thought he had spotted the New Mexico-class battleship Idaho.[21] The explosions caused massive damage. Indianapolis took on a heavy list, (the ship had a great deal of added armament and gun firing directors added as the war went on and was top heavy)[22] and settled by the bow. Twelve minutes later, she rolled completely over, then her stern rose into the air, and she plunged down. Some 300 of the 1,195 crewmen went down with the ship.[4] With few lifeboats and many without lifejackets, the remainder of the crew was set adrift.[23]

Rescue

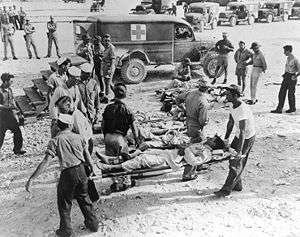

Navy command did not know of the ship's sinking until survivors were spotted three and a half days later. At 10:25 on 2 August, a PV-1 Ventura flown by Lieutenant Wilbur "Chuck" Gwinn and his copilot, Lieutenant Warren Colwell, spotted the men adrift while on a routine patrol flight.[24] Gwinn immediately dropped a life raft and radio transmitter. All air and surface units capable of rescue operations were dispatched to the scene at once. First to arrive was an amphibious PBY-5A Catalina patrol plane flown by Lieutenant Commander (USN) Robert Adrian "Adrian" Marks. Marks and his flight crew spotted the survivors and dropped life rafts; one raft was destroyed by the drop while others were too far away from the exhausted crew. Against standing orders not to land in open ocean, Marks took a vote of his crew and decided to land the aircraft in twelve-foot swells. He was able to maneuver his craft to pick up 56 survivors. Space in the plane was limited so Marks had men lashed to the wing with parachute cord. His actions rendered the aircraft unflyable. After nightfall, the destroyer escort USS Cecil J. Doyle (DE 368), the first of seven rescue ships, used its search light as a beacon and instilled hope in those still in the water. The Doyle and 6 other ships picked up the remaining survivors. After the rescue, Marks' plane was sunk by the Doyle as it was not able to be recovered.

The survivors suffered from lack of food and water (leading to dehydration and hypernatremia; some found rations, such as Spam and crackers, amongst the debris), exposure to the elements (leading to hypothermia and severe desquamation), and shark attacks, while some killed themselves or other survivors in various states of delirium and hallucinations.[25][26] Two of the rescued survivors, Robert Lee Shipman and Frederick Harrison, died in August 1945.

"Ocean of Fear", a 2007 episode of the Discovery Channel TV documentary series Shark Week, states that the sinking of Indianapolis resulted in the most shark attacks on humans in history, and attributes the attacks to the oceanic whitetip shark species. Tiger sharks might have also killed some sailors. The same show attributed most of the deaths on Indianapolis to exposure, salt poisoning, and thirst, with the dead being dragged off by sharks.[27]

Navy failure to learn of the sinking

The Headquarters of Commander Marianas on Guam and of the Commander Philippine Sea Frontier on Leyte, kept Operations plotting boards on which were plotted the positions of all vessels with which the headquarters were concerned. However, it was assumed that ships as large as Indianapolis would reach their destinations on time, unless reported otherwise. Therefore, their positions were based on predictions, and not on reports. On 31 July, when she should have arrived at Leyte, Indianapolis was removed from the board in the headquarters of Commander Marianas. She was also recorded as having arrived at Leyte by the headquarters of Commander Philippine Sea Frontier. LT Stuart B. Gibson, the operations officer under the Port Director, Tacloban, was the officer responsible for tracking the movements of Indianapolis. The vessel's failure to arrive on schedule was known at once to LT Gibson, who failed to investigate the matter and made no immediate report of the fact to his superiors. Gibson received a letter of reprimand in connection with the incident. The acting commander and operations officer of the Philippine Sea Frontier also received reprimands, while Gibson's immediate superior received a letter of admonition.[28]

In the first official statement, the Navy said that distress calls "were keyed by radio operators and possibly were actually transmitted" but that "no evidence has been developed that any distress message from the ship was received by any ship, aircraft or shore station".[28] Declassified records later showed that three stations received the signals but none acted upon the call. One commander was drunk, another had ordered his men not to disturb him, and a third thought it was a Japanese trap.[29]

Immediately prior to the attack, the seas had been moderate, the visibility fluctuating but poor in general, and Indianapolis had been steaming at 17 kn (20 mph; 31 km/h). When the ship didn't reach Leyte on the 31st, as scheduled, no report was made that she was overdue. This omission was due to a misunderstanding of the Movement Report System.

Court-martial of Captain McVay

Captain Charles B. McVay III, who had commanded Indianapolis since November 1944, survived the sinking and was among those rescued days later. In November 1945, he was court-martialed and convicted of "hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag". Several aspects of the court-martial were controversial. There was evidence that the Navy itself had placed the ship in harm's way. McVay's orders were to "zigzag at his discretion, weather permitting"; however, McVay was not informed that a Japanese submarine was operating in the vicinity of his route from Guam to Leyte. Further, Mochitsura Hashimoto, commander of I-58, testified that zigzagging would have made no difference.[30] Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz remitted McVay's sentence and restored him to active duty. McVay retired in 1949 as a rear admiral.[31]

While many of Indianapolis's survivors said McVay was not to blame for the sinking, the families of some of the men who died thought otherwise: "Merry Christmas! Our family's holiday would be a lot merrier if you hadn't killed my son", read one piece of mail.[32] The guilt that was placed on his shoulders mounted until he committed suicide in 1968, using his Navy-issued revolver. McVay was discovered on his front lawn by his gardener with a toy sailor in one hand, revolver in the other.[33] He was 70 years old.

McVay's record cleared

In 1996, sixth-grade student Hunter Scott began his research on the sinking of Indianapolis for a class history project, an assignment which eventually led to a United States Congressional investigation. In October 2000, the United States Congress passed a resolution that Captain McVay's record should state that "he is exonerated for the loss of Indianapolis". President Bill Clinton signed the resolution.[34] The resolution noted that, although several hundred ships of the US Navy were lost in combat in World War II, McVay was the only captain to be court-martialed for the sinking of his ship.[35]

In July 2001, the United States Secretary of the Navy ordered McVay's official Navy record cleared of all wrongdoing.[36][37]

Commanders

Commanders of USS Indianapolis.[38]

| Rank | Name | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Captain | John M. Smeallie | 15 November 1932 – 10 December 1934 |

| Captain | William S. McClintic | 10 December 1934 – 16 March 1936 |

| Captain | Henry Kent Hewitt | 16 March 1936 – 5 June 1937 |

| Captain | Thomas C. Kinkaid | 5 June 1937 – 1 July 1938 |

| Captain | John F. Shafroth, Jr. | 1 July 1938 – 1 October 1941 |

| Captain | Edward Hanson | 1 October 1941 – 11 July 1942 |

| Captain | Morton L. Deyo | 11 July 1942 – 12 January 1943 |

| Captain | Nicholas Vytlacil | 12 January 1943 – 30 July 1943 |

| Captain | Einar R. Johnson | 30 July 1943 – 18 November 1944 |

| Captain | Charles B. McVay III | 18 November 1944 – 30 July 1945 |

Awards

Discovery of the wreck

The wreck of Indianapolis is located in the Philippine Sea.[40] In July–August 2001, an expedition sought to find the wreckage through the use of side-scan sonar and underwater cameras mounted on a remotely operated vehicle. Four Indianapolis survivors accompanied the expedition, which was not successful. In June 2005, a second expedition was mounted to find the wreck. National Geographic covered the story and released it in July. Submersibles were launched to find any sign of wreckage. The only objects ever found, which have not been confirmed to have belonged to Indianapolis, were numerous pieces of metal of varying size found in the area of the reported sinking position (this was included in the National Geographic program "Finding of the USS Indianapolis").

In July 2016, new information came out regarding the possible location of Indianapolis when naval records said that LST-779 passed by the ship 11 hours before the torpedoes struck. Using this information, National Geographic planned to mount an expedition to search for the wreck in the summer of 2017.[41] Reports estimated that Indianapolis was actually 25 mi (40 km) west of the reported sinking position, in water over three mi (4,800 m) deep, and likely on the side of an underwater mountain.[42]

A year after the discovery of the records, the wreck was located by Paul Allen’s "USS Indianapolis Project" aboard Research Vessel Petrel [43] on 19 August 2017, at a depth of 18,000 feet (5,500 m).[44] The wreck is well preserved due to the great depth at which Indianapolis rests, which is the rocky mountain ranges of the North Philippine Sea.[45]

In September 2017, a map detailing the wreckage was released. The main part of the wreck lies in an impact crater. Its bow, which broke off before the ship sank, lies 1.5 miles (2.4 km) east. The two forward 8-inch guns, which also broke off on the surface and mark the ship's last position on the surface, lie 0.5 miles (0.80 km) east of the main wreck. The single 8-inch gun turret on the stern remains in place. Airplane wreckage from the ship lies about 0.6 miles (0.97 km) north of the main part of the wreck.[46]

Reunions

Since 1960, surviving crew members have been meeting for reunions in Indianapolis. For the 70th reunion, held 23–26 July 2015, 14 of the 32 remaining survivors attended. The reunions are open to anyone interested, and have more attendees each year, even as the number of survivors decreases from death. Held only periodically at first, biannually later on, the reunions have been held annually for the past several years. Every year, the survivors, most of them in their nineties, vote whether to continue.[47][48][49] Seven out of twenty living survivors attended the 2017 reunion.[50]

In popular culture

References to the Indianapolis sinking and aftermath have been adapted to film, stage, television, and popular culture. The incident itself was the subject of a made-for-television movie Mission of the Shark: The Saga of the USS Indianapolis (1991), with Stacy Keach portraying Captain Charles Butler McVay III.[51]

Probably the most well known fictional reference to the events occurs in the thriller film Jaws (1975), in a monologue by actor Robert Shaw, whose character Quint is depicted as a survivor of the Indianapolis sinking. The monologue emphasizes the numerous deaths caused by shark attacks after the sinking. John Milius was specifically brought into the production to write lines for this scene, and he based them on survivor stories. However, there are several historical inaccuracies in the monologue: the speech states the date of the sinking as 29 June 1945, when the ship was actually sunk just after midnight on 30 July. The speech further states that 1,100 men went into the water and 316 came out (in actuality, 321 came out, of whom 316 survived) and that because of the secrecy of the atom bomb mission no distress call was broadcast (while declassified Navy documents prove that the signal had been sent but did not elicit a response).[52]

A few years after the release of Jaws, co-writer Howard Sackler proposed making a prequel film based on the sinking of Indianapolis. The idea was ultimately rejected by then-Universal Studios president Sidney Sheinberg; the film instead would eventually go on to become the sequel Jaws 2.[53]

Sara Vladic directed USS Indianapolis: The Legacy, which tells the fate of USS Indianapolis using exclusively first-person accounts from the survivors of the sinking. This film was released in December 2015.[54]

USS Indianapolis: Men of Courage, starring Nicolas Cage, was released in October 2016, with Mario Van Peebles directing.[55][56]

Memorials

_Memorial.jpg)

The USS Indianapolis Museum had its grand opening on 7 July 2007, with its gallery in the Indiana War Memorial Museum at the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza.[57]

The USS Indianapolis National Memorial was dedicated on 2 August 1995. It is located on the Canal Walk in Indianapolis.[58] The heavy cruiser is depicted in limestone and granite and sits adjacent to the downtown canal. The crewmembers' names are listed on the monument, with special notations for those who lost their lives.[59]

In May 2011, highway I-465 around Indianapolis was named the USS Indianapolis Memorial Highway.[60]

Some material relating to Indianapolis is held by the Indiana State Museum. Her bell and a commissioning pennant are located at the Heslar Naval Armory.[61][62]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ship Nicknames". zuzuray.com. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Ships' Data, U. S. Naval Vessels". US Naval Department. 1 July 1935. pp. 16–23. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- 1 2 Rickard, J (19 December 2014). "USS Indianapolis (CA-35)". Historyofwar.org. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Neuman, Scott (23 March 2018). "Navy Admits To 70-Year Crew List Error In USS Indianapolis Disaster". NPR.org. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ CNN, Emanuella Grinberg. "USS Indianapolis wreckage found 72 years later". CNN. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ Bauer & Roberts 1991, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 Bauer & Roberts 1991, p. 138.

- 1 2 Miller 2001, p. 292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Silverstone 2007, p. 32.

- 1 2 Stille 2009, p. 30.

- 1 2 DANFS 1981, p. 433.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DANFS 1981, p. 434.

- ↑ Cook, Blanche (1999). Eleanor Roosevelt, vol. 2 (1933–1938). New York: Penguin. p. 398. ISBN 978-0140178944.

- ↑ "Marianas Turkey Shoot". cannon-lexington.com. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Ranulph Fiennes (6 October 2016). Fear: Our Ultimate Challenge. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-4736-1801-5.

- ↑ "Little Boy", the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, was also inscribed with numerous autographs and graffiti by ground crews who loaded it into the plane. One of them read: "Greetings to the Emperor from the men of the Indianapolis". Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (Simon & Schuster, 1986), 710.

- ↑ Raymond B. Lech (14 November 2000). The Tragic Fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis: The U.S. Navy's Worst Disaster at Sea. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-1-4616-6129-0.

- ↑ All Hands. Bureau of Naval Personnel. 1984.

- 1 2 Jeff Shaara (2012). The Final Storm: A Novel of the War in the Pacific. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-0-345-49795-6.

- ↑ Clayton Chun (20 January 2013). Japan 1945: From Operation Downfall to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-1-4728-0020-6.

- ↑ Bob Hackett and Sander Kingsepp (2008). "Submarine I-58: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ Budge, Kent G. "The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia: Portland Class, U.S. Heavy Cruisers". www.pwencycl.kgbudge.com. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ Lewis L. Haynes (July–August 1995). "Recollections of the sinking of USS Indianapolis (CA-35) by CAPT Lewis L. Haynes, MC (Medical Corps) (Ret.), the senior medical officer on board the ship". Navy Medicine. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ↑ Marks (April 1981) pp.48–50

- ↑ In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors

- ↑ "The Story (Delayed Rescue)". the USS Indianapolis National Memorial. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ "Discovery Channel's Shark Week: Ocean of Fear". Amazon.com. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- 1 2 "The Sinking of USS Indianapolis: Navy Department Press Release, Narrative of the Circumstances of the Loss of USS Indianapolis". U.S. Navy. 23 February 1946. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Timothy W. Maier (5 June 2000). "For The Good of the Navy". Insight on the News. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Mochitsura Hashimoto". ussindianapolis.org. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Captain McVay". ussindianapolis.org. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Steven Martinovich (16 April 2001). "Review of In Harm's Way". enterstageright.com. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Catarevas, Michael (4 November 2016). "Connecticut's Heroes Aboard the Doomed USS Indianapolis". Connecticut Magazine. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "Seeking Justice : Victory in Congress". ussindianapolis.org. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Legislation exonerating Captain McVay". ussindianapolis.org. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Thomas, Joseph (2005). Leadership Embodied. Naval Institute Press. pp. 112–117. ISBN 978-1-59114-860-9.

- ↑ Magin, Janis (13 July 2001). "Navy exonerates WWII captain". The Argus-Press. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ↑ Yarnall, Paul R. (22 August 2015). "NavSource Online: Cruiser Photo Archive". USS INDIANAPOLIS (CA 35). Navsource.org. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ At USS Indianapolis Museum Archived 30 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine. official website, in the left-hand column, click on "USS Indianapolis Battle Stars". Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ The coordinates given in this article are for the general area

- ↑ "New Lead Uncovered in Search for USS Indianapolis". 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "New Details On Final Resting Place Of USS Indianapolis - News - Indiana Public Media".

- ↑ "USS Indianapolis discovered 18,000 feet below Pacific surface". CNN. 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ "Wreckage of USS Indianapolis found in Philippine Sea". Indianapolis Star. 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ Werner, Ben (August 23, 2017). "Navy: USS Indianapolis Wreckage Well Preserved by Depth and Undersea Environment". USNI News. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ↑ Emanuella Grinberg. "USS Indianapolis wreckage found 72 years later". CNN.

"Wreckage of USS Indianapolis found". 25 August 2017.

Jamie Seidel (August 23, 2017). "USS Indianapolis, famous US Navy ship at the centre of". NewsComAu. - ↑ Hodges, Glenn (27 July 2015). "Warship's Last Survivors Recall Sinking in Shark-Infested Waters". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "USS Indianapolis Survivors Reunion". ussindyreunion.com. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ "Hundreds mark 70th anniversary of USS Indianapolis attack". 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Beilue: For the dwindling few, the USS Indianpolis reunion is too meaningful to ignore". Amarillo.com. Amarillo Globe-News. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Mission of the Shark: The Saga of the U.S.S. Indianapolis (1991)". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ↑ Jaws Dialogues

- ↑ Loynd 1978, pp. 24–5

- ↑ Vladic, Sara (2015-12-06), USS Indianapolis: The Legacy, William Roy Akines, Tom Balunis, George Barber, retrieved 2018-05-13

- ↑ Dave McNary. "'USS: Indianapolis' Shoot Set for June in Alabama (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety.

- ↑ Lowe, Kinsey (3 July 2015). "USS Indianapolis Production Delayed After Vintage Plane Waterlogged". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "USS Indianapolis Museum - Mission & Vision Statement". USS Indianapolis Museum. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Indiana War Memorial: USS Indianapolis Memorial". State of Indiana official website. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "USS Indianapolis". Indiana War Memorials Foundation. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ Network Indiana. "I-465 Renamed In Honor Of USS Indianapolis". Indiana Public Media. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION honoring the Heslar Naval Armory and its staff for their many contributionsto our nation and our state" (PDF). Indianapolis State Senate. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ↑ PacificWrecks.com. "Pacific Wrecks".

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Karl Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991), Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0313262029

- Dictionary of American naval fighting ships / Vol.3, Historical sketches : letters G through K, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy, 1981, ISBN 978-0160020186

- Fahey, James C. (1941). The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, Two-Ocean Fleet Edition. Ships and Aircraft.

- Harrell, David (as told by Edgar Harrell). Out of the Depths. 2005. ISBN 1-59781-166-1

- Hashimoto, Mochitsura (2010) [1954]. Sunk: The Story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet, 1941–1945. New York: Henry Holt; reprint: Progressive Press. ISBN 1-61577-581-1.

- Lech, Raymond B. 1982. All the Drowned Sailors, Jove Books.

- Loynd, Ray (1978), The Jaws 2 Log, London: W.H. Allen, ISBN 0-426-18868-3

- Marks, R. Adrian (April 1981). "America Was Well Represented". United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- Miller, David M. O. (2001), Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World, New York City: Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0760311271

- Newcomb, Richard F. 1958 and 2000. Abandon Ship!: The Saga of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, the Navy's Greatest Sea Disaster. ISBN 0-06-018471-X

- Silverstone, Paul (2007), The Navy of World War II, 1922–1947, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-0415978989

- Stanton, Doug (15 April 2003). In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7366-9. Publishers Weekly Notable Book Award; Massachusetts Book Award

- Stille, Mark (2009), USN Cruiser vs IJN Cruiser: Guadalcanal 1942, Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1846034664

- Taylor, Theodore (1954). The Magnificent Mitscher. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-850-2.

- Vincent, Lynn; Vladic, Sara (2018), Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man, Simon & Schuster .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Indianapolis (CA-35). |

- USS Indianapolis Museum official website

- USS Indianapolis Survivors Organization

- Another USS Indianapolis Survivors Organization

- Maritime Quest Indianapolis Pictures

- 1945 Kamikaze Damage Report – filed by Mare Island Naval Shipyard

- Allied Warships: USS Indianapolis (CA 35), Heavy cruiser of the Portland-class

- "USS Indianapolis Collection, 1898–1991 (Bulk 1945–1946 and 1984–1991), Collection Guide" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. 13 October 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- IndySurvivor.com - website and book by survivor Edgar Harrell, USMC

- Announcement of the Father Thomas Conway Memorial (June 2006). (At USS Indianapolis Museum official website, in the left-hand column, click on "2006 Museum Activities".)

- BBC Magazine

- Photo gallery of USS Indianapolis at NavSource Naval History

Coordinates: 12°2′N 134°48′E / 12.033°N 134.800°E

- USS Indianapolis(decked in flags) and the passenger liner Aquitania at the Statue of Liberty

- Mission of the Shark: The Saga of the U.S.S. Indianapolis (1991) on YouTube

- Missing The USS Indianapolis on YouTube, a History Channel documentary