RMS Carpathia

RMS Carpathia | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | RMS Carpathia |

| Owner: | Cunard Line |

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: |

|

| Builder: | C.S. Swan & Hunter, Newcastle upon Tyne[1] |

| Yard number: | 274 |

| Laid down: | 10 September 1901 |

| Launched: | 6 August 1902 |

| Completed: | February 1903 |

| Maiden voyage: | 5 May 1903 |

| In service: | 1903–1918 |

| Identification: | Radio call sign "MPA" |

| Fate: | Torpedoed southeast of Ireland and west of the Isles of Scilly by the Imperial German Navy submarine U-55, 17 July 1918 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Cunard Line transatlantic ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 13,555 GRT |

| Length: | 558 ft (170 m) |

| Beam: | 64 ft 6 in (19.66 m) |

| Draught: | 34 ft 7 in (10.54 m) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Capacity: |

|

RMS Carpathia was a Cunard Line transatlantic passenger steamship built by Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson in their shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

Carpathia made her maiden voyage in 1903 from Liverpool to Boston (Massachusetts), and continued on this route before being transferred to Mediterranean service in 1904. In April 1912, she became famous for rescuing the survivors of rival White Star Line's RMS Titanic after the latter struck an iceberg and sank with a loss of 1,517 lives in the North Atlantic Ocean. Carpathia braved dangerous ice fields and diverted all steam power to her engines in her rescue mission. She arrived only two hours after Titanic had sunk and rescued 705 survivors from the ship's lifeboats.

Carpathia herself was sunk on 17 July 1918 after being torpedoed by the German submarine SM U-55 off the southern Irish coast with a loss of five crew members.

Background

Around 1900, the Cunard Line faced tight competition from the British White Star Line and the German lines Norddeutscher Lloyd (North German Lloyd) and Hamburg America Line (HAPAG). Cunard's largest liners, as of 1898 RMS Campania and RMS Lucania, had a reputation for size and speed, both being of 12,950 gross register tons (GRT) and having held the "Blue Riband" for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.[2] However, Norddeutscher Lloyd's new liner SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had taken the Blue Riband from them in 1897, while White Star was planning to place a new 17,000-GRT liner, RMS Oceanic into service. Cunard also updated its fleet during this time, ordering three new liners, SS Ivernia, RMS Saxonia, and Carpathia.[3]

Rather than attempting to fully regain prestige by spending the additional money necessary to order liners that were fast enough to win back the Blue Riband from the German Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse or large enough to rival Oceanic in size, Cunard tried to maximize their profitability in order to remain solvent enough to fend off any takeover attempts by competing shipping conglomerate International Mercantile Marine Co.. The three new ships were not especially fast, as they were designed for the immigrant trade, but provided significant cost savings in fuel economy. The three ships became both instruments and models through which Cunard was able to successfully compete with its larger rivals – most notably IMM's lead company, White Star Line.[4]

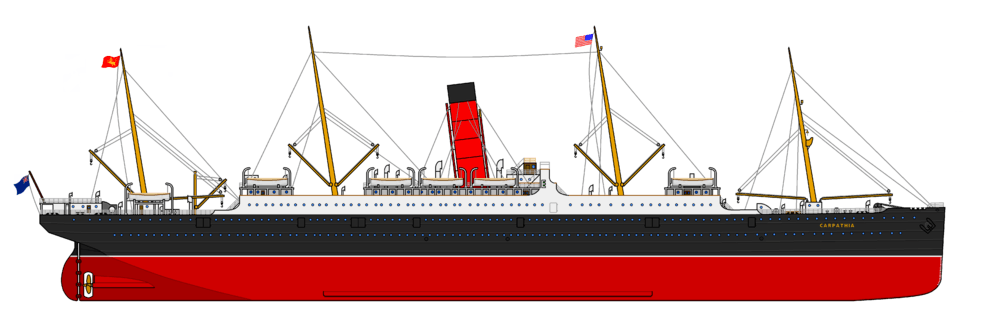

Carpathia was a modified design of the Ivernia-class ships, being approximately 40 feet (12 m) shorter than her "half-sisters." Like her predecessors, her design was based on a long hull, a low, well-balanced superstructure, and four masts fitted with cranes, allowing for effective handling of larger amounts of cargo than was customary on an ocean liner. Carpathia was designed with a single tall smokestack funnel to carry soot and smoke well clear of passenger areas.[5]

History

Design and Construction

RMS Carpathia was constructed by C. S. Swan & Hunter at their Newcastle upon Tyne, England shipyard for the Cunard Steamship Company, to operate between Liverpool and Boston alongside Ivernia and Saxonia.[6] She was laid down on 10 September 1901,[7] and launched on 6 August 1902, when she was christened by Miss Watson, daughter of the vice-chairman of the Cunard line.[8] She underwent her sea trials on a voyage from the River Tyne to the River Mersey between 22 and 25 April 1903.[9]

At the time of her launch, she was described as being 558 ft (170 m) long,[7] 64 ft 3 in (19.58 m) breadth, with gross register tonnage of 12,900.[10] As completed her gross register tonnage had increased to more than 13,500.[7] She was designed with "four complete steel decks, a steel orlop deck in Nos. 1 and 2 holds, and a bridge deck 290 ft. long for passenger, saloon and cabins" with a boat deck above this.[6] At the time she was launched, it was said that she was to be fitted for carrying 200 first-class and 600 third-class passengers and large quantities of frozen meat.[6][10] As completed, her capacity had increased to about 1,700 passengers.[7]

Despite being an intermediate liner designed for the second and third-class trade, Carpathia's interior accommodations were still quite comfortable and set a standard for the day. The dining saloon was described as decorated in "cream and gold, which combine effectively with the rich upholstery and mahogany of the...furniture...and old gold curtains screening the ports,"[5] and was capped by a stained-glass dome underneath an electrical fan for ventilation. The second-class accommodation also included a walnut-panelled smoking room located in the aft deckhouse and a handsome library at the forward end of the bridge (A) deck. After the 1905 renovation, these spaces would be converted to first-class accommodation. Third-class accommodation on Carpathia were extraordinarily generous for the time. The third-class dining saloon extended the full width of the ship and seated 300 passengers, with "walls panelled in polished oak and teak dado."[5] Third-class also included a smoking room and ladies' room located immediately forward of the dining saloon on the upper (C) deck, adjacent to the enclosed promenade (or open space) similar to the design on Ivernia and Saxonia.[5] Officers were berthed in the forward deckhouse on the bridge (A) deck, above the second-class dining saloon, while the captain's quarters was located on the boat deck immediately below the ship's bridge.

Carpathia's lower decks were well-ventilated by means of deck ventilators, supplemented by electric fans. The ventilation systems were designed to force fresh air over coiled thermotanks, which could be fed with cool water during the summer or steam during the winter, thus heating and cooling the ship as conditions warranted.[11] Although the ship was fully electrified with over 2,000 lamps, the ship still had backup oil lamps in the cabins when she entered service.[5]

Carpathia had seven single-ended boilers, fitted with the Howden forced draught system,[10] working at 210 psi (1,400 kPa),[6] which fed two independent sets of four-cylinder, four-crank, quadruple expansion engines, built by the Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Company, Ltd. of Wallsend, England[11] with cylinders of: 26 in (0.66 m), 37 in (0.94 m), 53 in (1.3 m), and 76 in (1.9 m) with a stroke of 54 in (1.4 m).[6][10] The engine power available allowed for an intended trial speed of 15.5 kn (17.8 mph; 28.7 km/h).[10]

Carpathia made her maiden voyage on 5 May 1903 from Liverpool, England,[7] to Boston, Massachusetts in the U.S.A., and ran services between New York City,[12] and Mediterranean ports at Gibraltar, Algiers, Naples, Trieste, and Fiume.[13]

Early service

Although lacking the speed and grand luxury of express liners (initially she had no first-class accommodations), Carpathia quickly developed a reputation as a comfortable ship, particularly in rough weather, due to her relatively wide breadth to length ratio, the use of bilge keels, and the lack of vibration typically found in powerful engines.[5][11] The ship became popular with both tourists and emigrants. During the summer season Carpathia operated mainly between Liverpool and New York City, and in the winter it traveled from New York City to the Mediterranean[7]

After Cunard partnered with the Royal Hungarian Sea Navigation Company "Adria" in 1904 Carpathia was more on the duty to transfer Hungarian emigrants.[14][15] As a result, Carpathia was renovated in 1905, increasing its capacity from 1,700 passengers to 2,550 passengers. Mainly third-class small cabins were converted to large shared dormitory rooms while adding first-class accommodation to areas that were previously second-class.[7] In 1912, her tonnage was 13,600 long tons (13,800 t),[16] and she had a capacity of 2,450 passengers (250 first and second-class combined, and 2,200 third-class.[16] She had a crew in 1912 of about 300, including 6 officers.[16] She carried 20 lifeboats.[16]

Titanic disaster

Carpathia departed from New York City on 11 April 1912 bound for Fiume, Austria-Hungary (now Rijeka, Croatia). Among its passengers were the American painters Colin Campbell Cooper and his wife Emma, author Philip Mauro, journalists Lewis Palmer Skidmore and Carlos Fayette Hurd, with their wives, Emily Vinton Skidmore and Katherine Cordell Hurd, photographer Dr. Francis H. Blackmarr, and Charles H. Marshall, whose three nieces were travelling aboard Titanic. Also on board were Hope Brown Chapin, honeymooning youngest daughter of former governor of Rhode Island, Russell Brown, Pittsburgh architect Charles M. Hutchison and wife, Sue Eva Rule, sister of Judge Virgil Rule of the St. Louis court of appeals, as well as Louis Mansfield Ogden, Esq., with his wife, Augusta Davies Ogden, a granddaughter of Alexander H. Rice.

On the night of 14 April, Carpathia's wireless operator, Harold Cottam, had missed previous messages from the Titanic, as he was on the bridge at the time.[17] After his shift ended at midnight, he continued listening to the transmitter before bed, and received messages from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, stating they had private traffic for Titanic. He thought he would be helpful and at 12:11 a.m. on 15 April sent a message to Titanic stating that Cape Cod had traffic for them. In reply he received Titanic's distress signal, stating that they had struck ice and were in need of immediate assistance.[17]

Cottam took the message and coordinates to the bridge, where the officers on watch were sceptical about the seriousness of the distress call.[18] Agitated, Cottam rushed down the ladder to the captain's cabin and awakened Captain Arthur Henry Rostron, who immediately sprang into action and "gave the order to turn the ship around",[19] and then "asked the operator if he was absolutely sure it was a distress signal from the Titanic".[19] The operator said that he had "received a distress signal from the Titanic, requiring immediate assistance", gave Titanic's position, and said that "he was absolutely certain of the message".[19] Whilst dressing, Rostron set a course for Titanic, and sent for the chief engineer and told "him to call another watch of stokers and make all possible speed to the Titanic, as she was in trouble."[19] Rostron testified that the distance to Titanic was 58 nmi (67 mi; 107 km) and took Carpathia three and a half hours.[19] At the same time, Rostron had Carpathia's crew prepare hot drinks and soup for the survivors, prepare the public rooms as dormitories, have doctors ready to treat any wounded survivors, and to have oil ready to pour down the lavatories to calm the water on the sides of the ship should the sea become rough.

Rostron ordered the ship's heating and hot water cut off in order to make as much steam as possible available for the engines, and had extra lookouts on watch to spot ice.[20][21] Cottam, meanwhile, messaged the Titanic that Carpathia was "coming as quickly as possible and expect to be there within four hours." Cottam refrained from sending more signals after this, trying to keep the air clear for Titanic's distress signals.[22] Carpathia reached the edge of the ice field by 2:45 a.m., and for the next two hours dodged icebergs as small growlers of ice ground along the hull plates.[22][19] The Carpathia arrived at the distress position at 4:00 a.m., approximately an hour and a half after the Titanic went down,[23] claiming more than 1,500 lives. For the next four and a half hours, the ship took on the 705 survivors of the disaster from Titanic's 20 lifeboats.[24] Survivors were given blankets and coffee, and then escorted by stewards to the dining rooms. Others went on deck to survey the ocean for any sign of their loved ones. Throughout the rescue, Carpathia's own passengers assisted in any way that they could.[25] By 9:00, the last survivor had been picked up, and Rostron gave the order to get underway.

After considering options for where to disembark the passengers, including the Azores (the destination with the least cost to the Cunard Line) and Halifax (the closest port, although along an ice-laden route), Rostron consulted with Bruce Ismay and decided to disembark the survivors in New York. News of the Titanic disaster spread on shore, and the humble Carpathia became the center of an intense media attention as it steamed westward toward New York at 14 knots. Hundreds of wireless messages were being sent from Cape Race and other shore stations addressed to Captain Rostron from relatives of Titanic passengers and journalists demanding details in exchange for money.[22] Rostron ordered that no news stories would be transmitted directly to the press, deferring such responsibilities to the White Star offices as Cottam provided details to Titanic's sister ship, Olympic. On Wednesday, 17 April, the scout cruiser USS Chester began escorting Carpathia to New York. Cottam, by then assisted by Titanic's junior wireless operator Harold Bride, transmitted the names of third-class survivors to Chester. Slowed by storms and fog since the early morning of Tuesday, 16 April, Carpathia finally arrived in New York on the evening of Thursday, 18 April 1912.[26]

For their rescue work, the crew of Carpathia were awarded medals by the survivors. Crew members were awarded bronze medals, officers silver, and Captain Rostron a silver cup and a gold medal, presented by Margaret Brown. Rostron was knighted by King George V, and was later a guest of President Taft at the White House, where he was presented with a Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honour the United States Congress could confer upon him.[27]

Service in the First World War

During the First World War, Carpathia was used to transfer Canadian and American Expeditionary Forces to Europe.[28] At least some of her voyages were in convoy, sailing from New York through Halifax to Liverpool and Glasgow.[29] Among her passengers during the war years was Frank Buckles, who went on to become the last surviving American veteran of the war.[30]

Sinking

On 15 July 1918, Carpathia departed Liverpool in a convoy bound for Boston carrying 57 passengers (36 saloon class and 21 steerage) and 166 crew. At 9:15 a.m. on the morning of 17 July, while sailing in the Southwest Approaches she was torpedoed near the No. 3 hatch on the port side by the Imperial German Navy submarine U-55, followed by a second which penetrated the engine room, killing three firemen and two trimmers.[31] As Carpathia began to settle by the head and list to port, Captain William Prothero gave the order to abandon ship. All passengers and the surviving crew members boarded the lifeboats as the vessel sank.[31] There were 218 survivors of the 223 aboard.[31] U-55 surfaced and fired a third torpedo into the ship near the gunner's rooms, resulting in a large explosion that doomed the ship.[31] U-55 started approaching the lifeboats when the Azalea-class sloop HMS Snowdrop arrived on the scene and drove away the submarine with gunfire before picking up the survivors from Carpathia.

Carpathia sank at 11:00 AM at a position recorded by Snowdrop as 49°25′N 10°25′W / 49.417°N 10.417°W, approximately 120 mi (190 km) west of Fastnet. At the time of her sinking, Carpathia was the fifth Cunard steamship sunk in as many weeks; the others being the Ascania, Ausonia, Dwinsk, and Valentia, leaving only five Cunarders afloat from the large pre-war fleet.[31]

Discovery and salvage works

On 9 September 1999, the Reuters and AP wire services reported that Argosy International Ltd., headed by Graham Jessop, son of the undersea explorer Keith Jessop, and sponsored by the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA), had discovered Carpathia's wreck in 600 ft (180 m) of water, 185 mi (298 km) west of Land's End.[32] Bad weather forced his ship to abandon the position before Jessop could verify the discovery using underwater cameras. However, when he returned to the location, the wreck was the Hamburg-America Line's Isis, sunk on 8 November 1936.[33]

In 2000, the American author and diver Clive Cussler announced that his organisation, NUMA, had found the true wreck of Carpathia in the Spring of that year,[34][35] at a depth of 500 ft (150 m).[36] After the submarine attack, Carpathia landed upright on the seabed. NUMA gave the approximate location of the wreck as 120 mi (190 km) west of Fastnet, Ireland.[37]

The wreck is owned by Premier Exhibitions Inc., formerly RMS Titanic Inc., which plans to recover objects from the wreck.[36]

Profile

Gallery

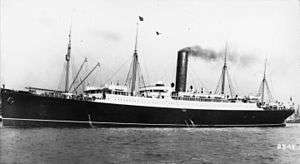

The grey-painted hull of Carpathia rests on the slipway, awaiting launch.

The grey-painted hull of Carpathia rests on the slipway, awaiting launch. Carpathia docked in New York following the rescue of Titanic's survivors

Carpathia docked in New York following the rescue of Titanic's survivors Margaret Brown (right) giving Captain Arthur Henry Rostron an award for his service in the rescue of the Titanic's survivors

Margaret Brown (right) giving Captain Arthur Henry Rostron an award for his service in the rescue of the Titanic's survivors- Rare on-deck photo of Carpathia passengers (circa 1914) unconnected with the Titanic disaster.

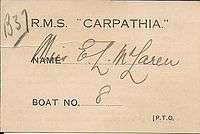

Life boat card

Life boat card

See also

- SS Californian, another vessel that was involved with the Titanic and perished in the First World War.

- SS Mount Temple, another vessel that was initially thought to be the "mystery ship" failing to respond to the Titanic's distress calls.

References

- ↑ "RMS Carpathia (1903)". www.tynebuiltships.co.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ N. R. P. Bonsor, North Atlantic Seaway, pp. 154–55, 1873.

- ↑ thegreatoceanliners.com Saxonia (I) 1900–1925

- ↑ J. H. Isherwood, "Intermediate Ship 'Saxonia' ", Sea Breezes 13 (1952), p. 411.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Cunard S.S. "Carpathia"", The Syren and Shipping Illustrated, p. 250-255, 6 May 1903 – via Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A floating dock and a new Cunarder" (PDF), The Engineer, p. 136, 8 August 1902 – via Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tikkanen, Amy (2 August 2016), "Carpathia, ship", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Launches at Newcastle". The Times (36840). London. 7 August 1902. p. 10.

- ↑ "The Cunard Steamer Carpathia". The Times (37065). London. 27 April 1903. col F, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "SS Carpathia" (PDF), The Engineer, p. 157, 15 August 1902 – via Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

- 1 2 3 "Steamship Carpathia.", Marine Engineering, p. 517, October 1903

- ↑ "(advertisement)". The Times (37085). London. 20 May 1903. col B, p. 2.

- ↑ "(advertisement)". The Times (37267). London. 18 December 1903. col B, p. 2.

- ↑ "100 éve történt (100 years ago)" (in Hungarian). Magyar Hajózásért Egyesület (Society for Hungarian Navigation). 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ↑ "Carpathia – az első mentőhajó 1. rész (Carpathia, the first rescue ship − part 1)" (in Hungarian). National Geographic (Hungary). Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- 1 2 3 4 "United States Senate Inquiry, Day 1, Testimony of Arthur H. Rostron, cont.", "Titanic" disaster, report of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, pursuant to S. Res. 283, directing the committee on commerce to investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star liner "Titanic.", 19 April 2012

- 1 2 "Day 15, Testimony of Harold T. Cottam". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. Titanic Inquiry Project. 24 May 1912. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ↑ Heath, Neil (20 October 2013). "The reluctant hero who took the Titanic's distress call". BBC News. Nottingham. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "United States Senate Inquiry, Day 1, Testimony of Arthur H. Rostron.", "Titanic" disaster, report of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, pursuant to S. Res. 283, directing the committee on commerce to investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star liner "Titanic.", 19 April 2012

- ↑ "RMS Carpathia" Retrieved 8 May 2014

- ↑ Cimino, Eric (Fall 2017). "Carpathia's Care for Titanic's Survivors". Voyage, Journal of the Titanic International Society. 101: 23–24.

- 1 2 3 Bisset, James G. P. (1959). Tramps and Ladies: My Early Years in Steamers. New York: Criterion Books. p. 297.

- ↑ "United States Senate Inquiry, Day 1, Testimony of Arthur H. Rostron, cont.", "Titanic" disaster, report of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, pursuant to S. Res. 283, directing the committee on commerce to investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star liner "Titanic.", 19 April 2012

- ↑ "Titanic Inquiry Project". Electronic copies of the inquiries into the disaster. Titanic Inquiry Project. 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ↑ Cimino. "Carpathia's Care": 25–27.

- ↑ "Testimony of Harold Bride". Titanic Inquiry Project.

- ↑ "Congressional Gold Medal Recipients | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ Official war diaries of CEF – 27 Batt. 15 May 1915

- ↑ Simmons, Perez; H. Davies, Alfred. Twentieth Engineers – France – 1917–1918–1919 (PDF). Portland, Oregon: Dimm & Sons Printing Co. Twentieth Engineers Publishing Association. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/01/us/01buckles.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Carpathia sunk; 5 of crew killed;" (PDF), The New York Times, p. 4, 20 July 1918

- ↑ "UK Titanic rescue ship 'found'". BBC News. 8 September 1999.

- ↑ Cussler, Clive; Delgado, James P. (2004). Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-55365-071-3.

- ↑ "Wreck of the Carpathia, Titanic's Rescuer, Found". National Underwater and Marine Agency. 27 April 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Reuters (23 September 2000). "Discovery Of R.M.S. Carpathia". Titanic-Titanic.com. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- 1 2 BBC News. "Dive to film Titanic rescue ship". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ↑ "Carpathia Rescue". National Underwater and Marine Agency. 25 February 2004. Archived from the original on 25 February 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

Further reading

- Butler, Daniel Allen. (2009). The Other Side of the Night: The Carpathia, the Californian, and the Night the Titanic Was Lost. Philadelphia: Casemate.

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. (1995). Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. New York: W. W. Norton & Compan., 2nd ed.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carpathia (ship, 1903). |