Government

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, often a state.[1]

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a means by which organizational policies are enforced, as well as a mechanism for determining policy. Each government has a kind of constitution, a statement of its governing principles and philosophy. Typically the philosophy chosen is some balance between the principle of individual freedom and the idea of absolute state authority (tyranny).

While all types of organizations have governance, the word government is often used more specifically to refer to the approximately 200 independent national governments on Earth, as well as subsidiary organizations.[2]

Historically prevalent forms of government include monarchy, aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, theocracy and tyranny. The main aspect of any philosophy of government is how political power is obtained, with the two main forms being electoral contest and hereditary succession.

Definitions and etymology

A government is the system to govern a state or community.[3]

The word government derives, ultimately, from the Greek verb κυβερνάω [kubernáo] (meaning to steer with gubernaculum (rudder), the metaphorical sense being attested in Plato's Ship of State).[4]

The Columbia Encyclopedia defines government as "a system of social control under which the right to make laws, and the right to enforce them, is vested in a particular group in society".[5]

While all types of organizations have governance, the word government is often used more specifically to refer to the approximately 200 independent national governments on Earth, as well as their subsidiary organizations.[2]

In the Commonwealth of Nations, the word government is also used more narrowly to refer to the ministry (collective executive), a collective group of people that exercises executive authority in a state or, metonymically, to the governing cabinet as part of the executive.

Finally, government is also sometimes used in English as a synonym for governance.

History

The moment and place that the phenomenon of human government developed is lost in time; however, history does record the formations of early governments. About 5,000 years ago, the first small city-states appeared.[6] By the third to second millenniums BC, some of these had developed into larger governed areas: Sumer, Ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization, and the Yellow River Civilization.[7]

The development of agriculture and water control projects were a catalyst for the development of governments.[8] For many thousands of years when people were hunter-gatherers and small scale farmers, humans lived in small, non-hierarchical and self-sufficient communities. On occasion a chief of a tribe was elected by various rituals or tests of strength to govern his tribe, sometimes with a group of elder tribesmen as a council. The human ability to precisely communicate abstract, learned information allowed humans to become ever more effective at agriculture,[9] and that allowed for ever increasing population densities.[6] David Christian explains how this resulted in states with laws and governments:[10]

As farming populations gathered in larger and denser communities, interactions between different groups increased and the social pressure rose until, in a striking parallel with star formation, new structures suddenly appeared, together with a new level of complexity. Like stars, cities and states reorganize and energize the smaller objects within their gravitational field.

— David Christian, p. 245, Maps of Time

Starting at the end of the 17th century, the prevalence of republican forms of government grew. The Glorious Revolution in England, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution contributed to the growth of representative forms of government. The Soviet Union was the first large country to have a Communist government.[2] Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, liberal democracy has become an even more prevalent form of government.[11]

In the nineteenth and twentieth century, there was a significant increase in the size and scale of government at the national level.[12] This included the regulation of corporations and the development of the welfare state.[11]

Political science

Classifying government

In political science, it has long been a goal to create a typology or taxonomy of polities, as typologies of political systems are not obvious.[13] It is especially important in the political science fields of comparative politics and international relations. Like all categories discerned within forms of government, the boundaries of government classifications are either fluid or ill-defined.

Superficially, all governments have an official or ideal form. The United States is a constitutional republic, while the former Soviet Union was a socialist republic. However self-identification is not objective, and as Kopstein and Lichbach argue, defining regimes can be tricky.[14] For example, elections are a defining characteristic of an electoral democracy, but in practice elections in the former Soviet Union were not "free and fair" and took place in a one-party state. Voltaire argued that "the Holy Roman Empire is neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire".[15] Many governments that officially call themselves a "democratic republic" are not democratic, nor a republic; they are usually a dictatorship de facto. Communist dictatorships have been especially prone to use this term. For example, the official name of North Vietnam was "The Democratic Republic of Vietnam". China uses a variant, "The People's Republic of China". Thus in many practical classifications it would not be considered democratic.

Identifying a form of government is also difficult because many political systems originate as socio-economic movements and are then carried into governments by parties naming themselves after those movements; all with competing political-ideologies. Experience with those movements in power, and the strong ties they may have to particular forms of government, can cause them to be considered as forms of government in themselves.

Other complications include general non-consensus or deliberate "distortion or bias" of reasonable technical definitions to political ideologies and associated forms of governing, due to the nature of politics in the modern era. For example: The meaning of "conservatism" in the United States has little in common with the way the word's definition is used elsewhere. As Ribuffo notes, "what Americans now call conservatism much of the world calls liberalism or neoliberalism".[16] Since the 1950s conservatism in the United States has been chiefly associated with the Republican Party. However, during the era of segregation many Southern Democrats were conservatives, and they played a key role in the Conservative Coalition that controlled Congress from 1937 to 1963.[17]

Social-political ambiguity

Every country in the world is ruled by a system of governance that combines at least three or more political or economic attributes. Additionally, opinions vary by individuals concerning the types and properties of governments that exist. "Shades of gray" are commonplace in any government and its corresponding classification. Even the most liberal democracies limit rival political activity to one extent or another while the most tyrannical dictatorships must organize a broad base of support thereby creating difficulties for "pigeonholing" governments into narrow categories. Examples include the claims of the United States as being a plutocracy rather than a democracy since some American voters believe elections are being manipulated by wealthy Super PACs.[18]

The dialectical forms of government

The Classical Greek philosopher Plato discusses five types of regimes: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny. Plato also assigns a man to each of these regimes to illustrate what they stand for. The tyrannical man would represent tyranny for example. These five regimes progressively degenerate starting with aristocracy at the top and tyranny at the bottom.

Forms of government

One method of classifying governments is through which people have the authority to rule. This can either be one person (an autocracy, such as monarchy), a select group of people (an aristocracy), or the people as a whole (a democracy, such as a republic).

The division of governments as monarchy, aristocracy and democracy has been used since Aristotle's Politics. In his book Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes expands on this classification.

The difference of Commonwealths consisteth in the difference of the sovereign, or the person representative of all and every one of the multitude. And because the sovereignty is either in one man, or in an assembly of more than one; and into that assembly either every man hath right to enter, or not every one, but certain men distinguished from the rest; it is manifest there can be but three kinds of Commonwealth. For the representative must needs be one man, or more; and if more, then it is the assembly of all, or but of a part. When the representative is one man, then is the Commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular Commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy. Other kind of Commonwealth there can be none: for either one, or more, or all, must have the sovereign power (which I have shown to be indivisible) entire.[19]

Autocracy

An autocracy is a system of government in which supreme power is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject to neither external legal restraints nor regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perhaps for the implicit threat of a coup d'état or mass insurrection).[20]

A despotism is a government ruled by a single entity with absolute power, whose decisions are subject to neither external legal restraints nor regular mechanisms of popular control (except perhaps for implicit threat). That entity may be an individual, as in an autocracy, or it may be a group, as in an oligarchy. The word despotism means to "rule in the fashion of despots".

A monarchy is where a family or group of families (rarely another type of group), called the royalty, represents national identity, with power traditionally assigned to one of its individuals, called the monarch, who mostly rule kingdoms. The actual role of the monarch and other members of royalty varies from purely symbolical (crowned republic) to partial and restricted (constitutional monarchy) to completely despotic (absolute monarchy). Traditionally and in most cases, the post of the monarch is inherited, but there are also elective monarchies where the monarch is elected.

Aristocracy

Aristocracy (Greek ἀριστοκρατία aristokratía, from ἄριστος aristos "excellent", and κράτος kratos "power") is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class.[21]

Many monarchies were aristocracies, although in modern constitutional monarchies the monarch himself or herself has little real power. The term "Aristocracy" could also refer to the non-peasant, non-servant, and non-city classes in the Feudal system.

An oligarchy is ruled by a small group of segregated, powerful or influential people who usually share similar interests or family relations. These people may spread power and elect candidates equally or not equally. An oligarchy is different from a true democracy because very few people are given the chance to change things. An oligarchy does not have to be hereditary or monarchic. An oligarchy does not have one clear ruler but several rulers.

Some historical examples of oligarchy are the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Some critics of representative democracy think of the United States as an oligarchy. The Athenian democracy used sortition to elect candidates, almost always male, Greek, educated citizens holding a minimum of land, wealth and status.

A theocracy is rule by a religious elite; a system of governance composed of religious institutions in which the state and the church are traditionally or constitutionally the same entity. The Vatican's (see Pope), Iran's (see Supreme Leader), Tibetan government's (see Dalai Lama), Caliphates and other Islamic states are historically considered theocracies.

Democracy

In a general sense, in a democracy, all the people of a state or polity are involved in making decisions about its affairs. Also refer to the rule by a government chosen by election where most of the populace are enfranchised. The key distinction between a democracy and other forms of constitutional government is usually taken to be that the right to vote is not limited by a person's wealth or race (the main qualification for enfranchisement is usually having reached a certain age). A democratic government is, therefore, one supported (at least at the time of the election) by a majority of the populace (provided the election was held fairly). A "majority" may be defined in different ways. There are many "power-sharing" (usually in countries where people mainly identify themselves by race or religion) or "electoral-college" or "constituency" systems where the government is not chosen by a simple one-vote-per-person headcount.

In democracies, large proportions of the population may vote, either to make decisions or to choose representatives to make decisions. Commonly significant in democracies are political parties, which are groups of people with similar ideas about how a country or region should be governed. Different political parties have different ideas about how the government should handle different problems.

Liberal democracy is a variant of democracy. It is a form of government in which representative democracy operates under the principles of liberalism. It is characterised by fair, free, and competitive elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, and the protection of human rights and civil liberties for all persons. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either formally written or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. After a period of sustained expansion throughout the 20th century, liberal democracy became the predominant political system in the world. A liberal democracy may take various constitutional forms: it may be a republic, such as France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Taiwan, or the United States; or a constitutional monarchy, such as Japan, Spain, or the United Kingdom. It may have a presidential system (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, or the United States), a semi-presidential system (France, Portugal, or Taiwan), or a parliamentary system (Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, India, Italy, New Zealand, or the United Kingdom).

Republics

A republic is a form of government in which the country is considered a "public matter" (Latin: res publica), not the private concern or property of the rulers, and where offices of states are subsequently directly or indirectly elected or appointed rather than inherited. The people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people.[22][23] A common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of state is not a monarch.[24][25] Montesquieu included both democracies, where all the people have a share in rule, and aristocracies or oligarchies, where only some of the people rule, as republican forms of government.[26]

Other terms used to describe different republics include Democratic republic, Parliamentary republic, Federal republic, and Islamic Republic.

Scope of government

Rule by authoritarian governments is identified in societies where a specific set of people possess the authority of the state in a republic or union. It is a political system controlled by unelected rulers who usually permit some degree of individual freedom. Rule by a totalitarian government is characterised by a highly centralised and coercive authority that regulates nearly every aspect of public and private life.

In contrast, a constitutional republic is rule by a government whose powers are limited by law or a formal constitution, and chosen by a vote amongst at least some sections of the populace (Ancient Sparta was in its own terms a republic, though most inhabitants were disenfranchised). Republics that exclude sections of the populace from participation will typically claim to represent all citizens (by defining people without the vote as "non-citizens"). Examples include the United States, South Africa, India, etc.

Federalism

Federalism is a political concept in which a group of members are bound together by covenant (Latin: foedus, covenant) with a governing representative head. The term "federalism" is also used to describe a system of government in which sovereignty is constitutionally divided between a central governing authority and constituent political units (such as states or provinces). Federalism is a system based upon democratic rules and institutions in which the power to govern is shared between national and provincial/state governments, creating what is often called a federation. Proponents are often called federalists.

Economic systems

Historically, most political systems originated as socioeconomic ideologies. Experience with those movements in power and the strong ties they may have to particular forms of government can cause them to be considered as forms of government in themselves.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Capitalism | A social-economic system in which the means of production (machines, tools, factories, etc.) are under private ownership and their use is for profit. |

| Communism | A social-economic system in which means of production are commonly owned (either by the people directly, through the commune or by communist society), and production is undertaken for use, rather than for profit.[27][28] Communist society is thus stateless, classless, moneyless, and democratic. |

| Distributism | A social-economic system in which widespread property ownership as fundamental right;[29] the means of production are spread as widely as possible rather than being centralized under the control of the state (state socialism), a few individuals (plutocracy), or corporations (corporatocracy).[30] Distributism fundamentally opposes socialism and capitalism,[31][32] which distributists view as equally flawed and exploitative. In contrast, distributism seeks to subordinate economic activity to human life as a whole, to our spiritual life, our intellectual life, our family life".[33] |

| Feudalism | A social-economic system of land ownership and duties. Under feudalism, all the land in a kingdom was the king's. However, the king would give some of the land to the lords or nobles who fought for him. These presents of land were called manors. Then the nobles gave some of their land to vassals. The vassals then had to do duties for the nobles. The lands of vassals were called fiefs. |

| Socialism | A social-economic system in which workers, democratically and socially own the means of production[34] and the economic framework may be decentralized, distributed or centralized planned or self-managed in autonomous economic units.[35] Public services would be commonly, collectively, or state owned, such as healthcare and education. |

| Statism | A social-economic system that concentrates power in the state at the expense of individual freedom. Among other variants, the term subsumes theocracy, absolute monarchy, Nazism, fascism, authoritarian socialism, and plain, unadorned dictatorship. Such variants differ on matters of form, tactics and ideology. |

| Welfare state | A social-economic system in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of equality of opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. |

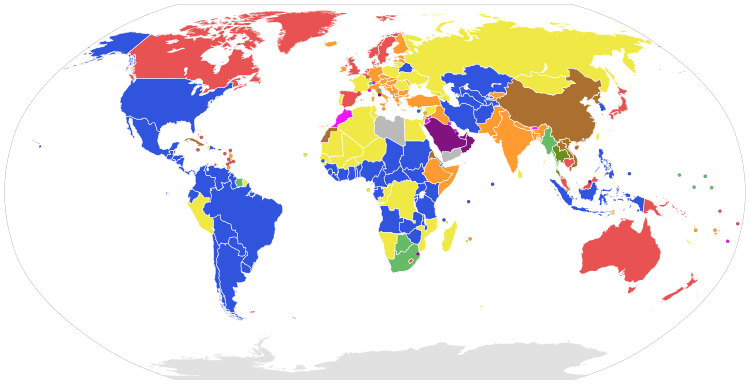

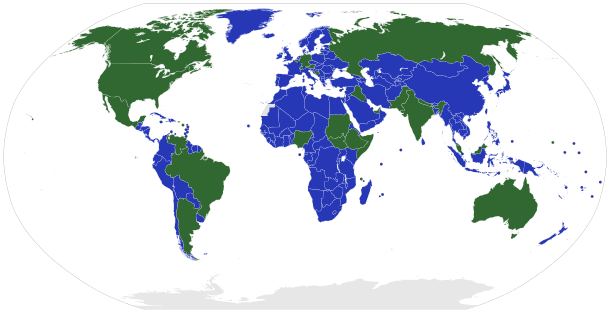

Maps

|

Full Democracies

9–10

8–9

|

Flawed Democracies

7–8

6–7

|

Hybrid Regimes

5–6

4–5

|

Authoritarian Regimes

3–4

2–3

0–2

|

See also

- List of forms of government

- Central government

- Civics

- Comparative government

- Constitutional economics

- Deep state

- Digital democracy

- E-Government

- History of politics

- Legal rights

- List of countries by system of government

- List of European Union member states by political system

- Ministry

- Political economy

- Political history

- Politics

- Prime ministerial government

- State (polity)

- Voting system

- World government

Principles

Certain major characteristics are defining of certain types; others are historically associated with certain types of government.

- Rule according to higher law (unwritten ethical principles) vs. written constitutionalism

- Separation of church and state or free church vs. state religion

- Civilian control of the military vs. stratocracy

- Totalitarianism or authoritarianism vs. libertarianism

- Majority rule or parliamentary sovereignty vs. constitution or bill of rights with separation of powers and supermajority rules to prevent tyranny of the majority and protect minority rights

- Androcracy (patriarchy) or gynarchy (matriarchy) vs. gender quotas, gender equality provision, or silence on the matter

Autonomy

This list focuses on differing approaches that political systems take to the distribution of sovereignty, and the autonomy of regions within the state.

- Sovereignty located exclusively at the centre of political jurisdiction.

- Sovereignty located at the centre and in peripheral areas.

- Diverging degrees of sovereignty.

- Alliance

- Asymmetrical federalism

- Federacy

- Associated state

- Corpus separatum

- Colony

- Crown colony

- Chartered company

- Dependent territory

- Occupied territory

- Occupied zone

- Mandate

- Exclusive mandate

- Military Frontier

- Neutral zone

- Colonial dependency

- Protectorate

- Vassal state

- Satellite state

- Puppet state

- Thalassocracy

- Unrecognized state

- Provisional government

- Territorial disputes

- Non-self-governing territories

- League of Nations

- League

- Commonwealth

- Decentralisation and devolution (powers redistributed from central to regional or local governments)

References

- ↑ "government". Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press. November 2010.

- 1 2 3 International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier. 2001. ISBN 0-08-043076-7.

- ↑ "government". OxfordDictionaries.com. 2010.

- ↑ The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopædia Britannica Company. 1911.

- ↑ Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th edition. Columbia University Press. 2000.

- 1 2 Christian 2004, p. 245.

- ↑ Christian 2004, p. 294.

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica (15th edition)

- ↑ Christian 2004, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Christian, David (2004). Maps of Time. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24476-1.

- 1 2 Adam Kuper and Jessica Kuper (ed.). The Social Science Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47635-5.

- ↑ The Oxford Handbook of State and Local Government, 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-957967-9

- ↑ Lewellen, Ted C. Political Anthropology: An Introduction Third Edition. Praeger Publishers; 3rd edition (2003)

- ↑ Comparative politics : interests, identities, and institutions in a changing global order, Jeffrey Kopstein, Mark Lichbach (eds.), 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521708400, p. 4.

- ↑ Renna, Thomas (Sep 2015). "The Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire". Michigan Academician. 42 (1): 60–75. doi:10.7245/0026-2005-42.1.60.

- ↑ Leo P. Ribuffo, "20 Suggestions for Studying the Right now that Studying the Right is Trendy," Historically Speaking Jan 2011 v.12#1 pp. 2–6, quote on p. 6

- ↑ Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968, p. 12, "...conservative southern Democrats viewed warily the potential of New Deal programs to threaten the region's economic dependence on cheap labor while stirring the democratic ambitions of the disfranchised and undermining white supremacy.", The University of North Carolina Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-8078-4910-1

- ↑ "Plutocrats – The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else" Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Chrystia Free land is Global Editor-at-Large at Reuters news agency, following years of service at the Financial Times both in New York and London. She was the deputy editor of Canada's Globe and Mail and has reported for the Financial Times, Economist, and Washington Post. She lives in New York City.

- ↑ Hobbes, Thomas.

- ↑ Paul M. Johnson. "Autocracy: A Glossary of Political Economy Terms". Auburn.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ "Aristocracy". Oxford English Dictionary. December 1989. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (1748), Bk. II, ch. 1.

- ↑ "Republic". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "republic". WordNet 3.0. Dictionary.com. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ↑ "Republic". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws, Bk. II, ch. 2–3.

- ↑ Steele, David Ramsay (September 1999). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. p. 66. ISBN 978-0875484495.

Marx distinguishes between two phases of marketless communism: an initial phase, with labor vouchers, and a higher phase, with free access.

- ↑ Busky, Donald F. (July 20, 2000). Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey. Praeger. p. 4. ISBN 978-0275968861.

Communism would mean free distribution of goods and services. The communist slogan, 'From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs' (as opposed to 'work') would then rule

- ↑ Shiach, Morag (2004). Modernism, Labour and Selfhood in British Literature and Culture, 1890–1930. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-521-83459-9

- ↑ Zwick, Mark and Louise (2004). The Catholic Worker Movement: Intellectual and Spiritual Origins . Paulist Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8091-4315-3

- ↑ Boyle, David; Simms, Andrew (2009). The New Economics. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84407-675-8

- ↑ Novak, Michael; Younkins, Edward W. (2001). Three in One: Essays on Democratic Capitalism, 1976–2000. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-7425-1171-2

- ↑ Storck, Thomas. "Capitalism and Distributism: two systems at war," in Beyond Capitalism & Socialism. Tobias J. Lanz, ed. IHS Press, 2008. p. 75

- ↑ Sinclair, Upton (1918-01-01). Upton Sinclair's: A Monthly Magazine: for Social Justice, by Peaceful Means If Possible.

Socialism, you see, is a bird with two wings. The definition is 'social ownership and democratic control of the instruments and means of production.'

- ↑ Schweickart, David. Democratic Socialism Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice (2006): "Virtually all (democratic) socialists have distanced themselves from the economic model long synonymous with 'socialism,' i.e. the Soviet model of a non-market, centrally-planned economy...Some have endorsed the concept of 'market socialism,' a post-capitalist economy that retains market competition, but socializes the means of production, and, in some versions, extends democracy to the workplace. Some hold out for a non-market, participatory economy. All democratic socialists agree on the need for a democratic alternative to capitalism."

- ↑ "Democracy Index 2017 – Economist Intelligence Unit" (PDF). EIU.com. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

Bibliography

- American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-82517-2

Further reading

- Krader, Lawrence (1968). Formation of the State, in Foundations of Modern Anthropology Series. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 118 pp.

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith (2011). The Dictator's Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. Random House. p. 272. ISBN 9781610390446. OCLC 701015473.

- Friedrich, Carl J.; Brzezinski, Zbigniew K. (1965). Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (2nd ed.). Praeger.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-63315-9.

- William J. Dobson (2013). The Dictator's Learning Curve: Inside the Global Battle for Democracy. Anchor. ISBN 978-0307477552.

External links

| Look up government in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Appendix:List of forms of government in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Government |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Government. |

- The Phrontistery Word List: Types of Government and Leadership

- What Are the Different Types of Governments?

- Types of Governments from Historical Atlas of the 20th Century

- Other classifications examples from Historical Atlas of the 20th Century

- World Affairs: Types of Government

- Regime Types

- CBBC Newsround: types of government

- Bill Moyers: Plutocracy Rising

- Phobiocracy by Chris Claypoole