Sonargaon

| সোনারগাঁও | |

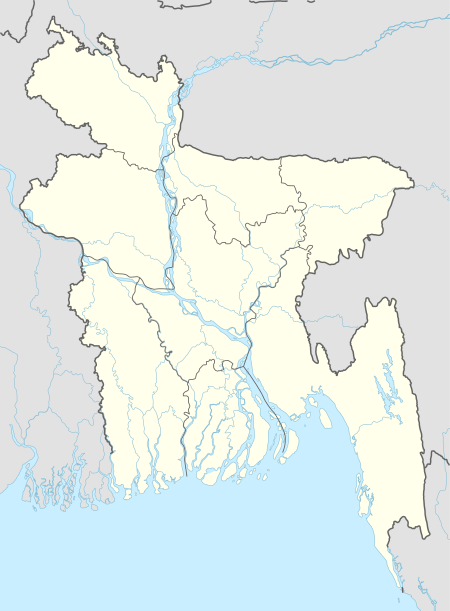

Shown within Bangladesh | |

| Location | Near Narayanganj |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 23°38′51″N 90°35′52″E / 23.64750°N 90.59778°ECoordinates: 23°38′51″N 90°35′52″E / 23.64750°N 90.59778°E |

Sonargaon (Bengali: সোনারগাঁও; also transcribed as Sunārgāon,[1] meaning Village of Gold) was a historic administrative, commercial and maritime centre in Bengal. Situated in the centre of the Ganges delta, it was the seat of the medieval Muslim rulers and governors of eastern Bengal. Sonargaon was described by numerous historic travellers, including Ibn Battuta, Ma Huan, Niccolò de' Conti and Ralph Fitch as a thriving centre of trade and commerce.

It was an administrative centre of Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah's sultanate, the Bengal Sultanate and the Kingdom of Bhati.

The area is located near the modern industrial river port of Narayanganj in Bangladesh. Today, the name Sonargaon survives as the Sonargaon Upazila (Sonargaon Subregion) in the region.[2]

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bangladesh |

|

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Modern

|

|

Related articles |

|

|

Pre-Muslim period

The name Sonargaon came as the Bangla version of the ancient name Suvarnagrama.[2] Buddhist ruler Danujamadhava Dasharathadeva shifted his capital to Suvarnagrama from Bikrampur sometime in the middle of the 13th century.[2] In the early 14th century, Buddhist rule in this kingdom ended when Shamsuddin Firoz Shah (reigned 1301–1322) of Lakhnauti conquered it.[3]

Muslim period

Muslim settlers first arrive in Sonargaon region in around 1281.[5] Sharfuddin Abu Tawwamah, a medieval Sufi saint and Islamic philosopher came and settled here sometime between 1282 and 1287.[6] He then established his Khanqah and founded a Madrasa.

Firoz Shah built a mint in Sonargaon from where a large number of coins were issued.[3] When he died in 1322, his son, Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah, replaced him as the ruler. In 1324 Delhi Sultan, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, declared war against him and after the battle, Bahadur Shah was captured and Bengal, including Sonargaon, became a province of Delhi Sultanate.[7] The same year, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, son and successor of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, released him and appointed him as the governor of Sonargaon province.[8]

After 4 years of governorship, in 1328, Bahadur Shah declared independence of Bengal. Delhi Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq sent his general, Bahram Khan, to depose him. In the battle, Bahadur Shah was defeated and killed. Bahram Khan recaptured Sonargaon for the Delhi Sultanate and he was also appointed the governor of Sonargaon.[9]

When Bahram Khan died in 1338, his armour-bearer, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, declared himself the independent Sultan of Sonargaon.[5] Fakhruddin sponsored several construction projects, including a trunk road and raised embankments, along with mosques and tombs.[10] 14th century Moroccan traveller, Ibn Batuta, after visiting the capital in 1346, described Fakhruddin as "a distinguished sovereign who loved strangers, particularly the fakirs and sufis".[10] After the death of Fakhruddin in 1349, Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah became the next independent ruler of Sonargaon.[11]

Ilyas Shah, the independent ruler of Lakhnauti, attacked Sonargaon in 1352. After defeating Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah, he became the sole ruler of whole Bengal for the first time in history and thus he became the founder of a sultanate of the unified Bengal.[12]

A squadron of the Chinese fleet of Zheng He, commanded by the eunuch Hong Bao, visited Sonargaon in 1432. The information about that expedition comes from the book of one of its participants, the Muslim translator Ma Huan.[1] In 1451 Huan wrote his experience in details in his book Yingyai Shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores).

Sonargaon is the eastern terminus of the Grand Trunk Road, which was built by the Pashtun emperor Sher Shah Suri and extended approximately 2500 kilometres from Bangladesh across northern India and Pakistan to Kabul in Afghanistan.[5]

Isa Khan's rule

When Taj Khan Karrani was the independent Afghan ruler of Bengal, Isa Khan obtained an estate in Sonargaon and Maheswardi Pargana in 1564 as a vassal of the Karrani rulers. Isa Khan gradually increased his strength and in 1571 he was designated as the ruler of the whole Bhati region. In 1575 he helped Daud Khan Karrani fight the Mughal flotilla in the vicinity of Sonargaon.[13]

Daud Khan Karrani died in the Battle of Raj Mahal against Mughals in 1576. Akbar then made Isa Khan the zamindar of Sonargaon, making him one of the Baro-Bhuiyans. However, he continued resisting Mughal rule. With the help of his allies, he stood defiant against Mughals in battle against Subahdar Khan Jahan in 1578, Subahdar Shahbaz Khan in 1584 and Durjan Singh in 1597. Isa Khan died in September 1599. His son, Musa Khan, then took control of the Bhati region. But after the defeat of Musa Khan on 10 July 1610[14] by Islam Khan, the army general of Mughals, Sonargaon became one of the sarkars of Bengal subah. The capital of Bengal was then shifted to Jahangirnagar (later named Dhaka).

British period

Panam City was established in the late 19th century in the vicinity of Sonargaon as a trading centre of cotton fabrics during British rule. Hindu cloth merchants built their residential houses following colonial style with inspiration derived from European sources.[2] Today this area is protected under the Department of Archaeology of Bangladesh. The city was linked with the main city area by three brick bridges – Panam Bridge, Dalalpur Bridge and PanamNagar Bridge – during the Mughal period. The bridges are still in use.

Sonakanda Fort is a Mughal river-fort located on the bank of the Shitalakshya River at Bandar.[15]

Bangladesh period

Lok Shilpa Jadughar Bangladesh Folk Arts and Crafts Foundation of Sonargaon was established by Bangladeshi painter Joynul Abedin on 12 March 1975.[5] The house, originally called Bara Sardar Bari, was built in 1901.

On 15 February 1984, Narayanganj subdivision was upgraded to a district by the Government of Bangladesh.[16] Hence Sonargaon became a subdistrict of Narayanganj District of Dhaka division.

Due to the many threats to preservation (including flooding and vandalism), Sonargaon was placed in 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund.[17]

Trade

By the 14th century Sonargaon became a commercial port. Trade activities were mentioned by travellers like Ibn Batuta, Ma Huan and Ralph Fitch.[2] Maritime ships travelled between Sonargaon and southeast/west Asian countries.[2] Muslin was produced in this region.

See also

References

- 1 2 Duarte Barbosa; Mansel Longworth Dames (1996) [1918–1921], The book of Duarte Barbosa : An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and Their Inhabitants, Asian Educational Services, pp. 138–139, ISBN 81-206-0451-2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Muazzam Hussain Khan, Sonargaon Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- 1 2 ABM Shamsuddin Ahmed, Shamsuddin Firuz Shah Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ↑ Dreyer, Edward L. (2006), Zheng He: China and the oceans in the early Ming dynasty, 1405–1433, The library of world biography, Pearson Longman, ISBN 0-321-08443-8

- 1 2 3 4 Gope, Rabindra (2011). A visitor's guide to the Sonargaon Museum. p. 3. ISBN 978-984-33-2004-9.

- ↑ Muazzam Hussain Khan, Sharfuddin Abu Tawwamah Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 18 January 2012

- ↑ Kingdom of South Asia Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Khan, Muazzam Hussain. "Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah". Banglapedia. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Muazzam Hussain Khan, Tatar Khan Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 18 January 2012

- 1 2 Muazzam Hussain Khan, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 23 April 2011

- ↑ Muazzam Hussain Khan, Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ↑ ABM Shamsuddin Ahmed, Iliyas Shah Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ↑ AA Sheikh Md Asrarul Hoque Chisti, Isa Khan Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 23 January 2012

- ↑ Feroz, M A Hannan (2009). 400 years of Dhaka. Ittyadi. p. 12.

- ↑ Ayesha Begum, Sonakanda Fort Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ↑ Md Solaiman, Narayanganj Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 February 2012

- ↑ World Monuments Fund. "2008 World Monuments Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. World Monuments Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

Farhana shirin, sonargaon, gonipara, narayangonj, A.jabbar M.name:Sahara khatun

Further reading

- Kazi Azizul Islam and Tania Sharmeen (5 July 2005). "Panam Among World's 100 Endangered Historic Sites". News from Bangladesh.

- Roy, Pinaki (9 July 2004). "Panam Nagar's Fate in Limbo". The Daily Star.

- Ali, Tawfique (26 April 2007). "Unscientific Restoration Defacing Heritage". The Daily Star, Vol 5 num 1031.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sonargaon. |