Palaiologos

| Palaiologos Παλαιολόγος Palaeologus, Palaeologue | |

|---|---|

| Imperial Family | |

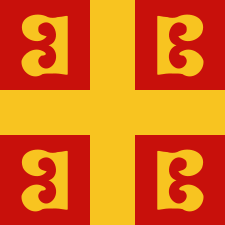

Double-headed eagle with the family cypher | |

| Country | Byzantine Empire |

| Ethnicity | Greek[1] |

| Founded | 11th century |

| Founder | Nikephoros Palaiologos (first known) |

| Final ruler |

Constantine XI Palaiologos (Byzantine Empire) Margaret Paleologa (Montferrat) |

| Titles | |

| Style(s) |

"Augustus" "Basileus" "Autokrator" |

| Dissolution | 1533 |

| Cadet branches |

Claimants:

|

| Palaiologan dynasty | |||

| Chronology | |||

| Michael VIII | 1259–1282 | ||

| with Andronikos II as co-emperor, 1261–1282 | |||

| Andronikos II | 1282–1328 | ||

| with Michael IX (1294–1320) and Andronikos III (1321–1328) as co-emperors | |||

| Andronikos III | 1328–1341 | ||

| John V | 1341–1391 | ||

| with John VI Kantakouzenos (1347–1354), Matthew Kantakouzenos (1342–1357) and Manuel II (1373–1391) as co-emperors | |||

| Usurpation of Andronikos IV | 1376–1379 | ||

| Usurpation of John VII | 1390 | ||

| Manuel II | 1391–1425 | ||

| with Andronikos V (1403–1407) and John VIII (ca. 1416–1425) as co-emperors | |||

| John VIII | 1425–1448 | ||

| Constantine XI | 1448–1453 | ||

| Succession | |||

| Preceded by Laskarids of Nicaea |

Followed by Ottoman conquest | ||

The Palaiologos (pl. Palaiologoi; Greek: Παλαιολόγος, pl. Παλαιολόγοι), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was the name of a Byzantine Greek[1] family, which rose to nobility and ultimately produced the last ruling dynasty of the Byzantine Empire.

Founded by the 11th-century general Nikephoros Palaiologos and his son George, the family rose to the highest aristocratic circles through its marriage into the Doukas and Komnenos dynasties. After the Fourth Crusade, members of the family fled to the neighboring Empire of Nicaea, where Michael VIII Palaiologos became co-emperor in 1259, recaptured Constantinople and was crowned sole emperor of the Byzantine Empire in 1261.[2] His descendants ruled the empire until the Fall of Constantinople at the hands of the Ottoman Turks on May 29, 1453, becoming the longest-lived dynasty in Byzantine history; some continued to be prominent in Ottoman society long afterwards. A branch of the Palaiologos became the feudal lords of Montferrat, Italy. This inheritance was eventually incorporated by marriage to the Gonzaga family, rulers of the Duchy of Mantua, who are descendants of the Palaiologoi of Montferrat.

Dynastic genealogy

The origins of the Palaiologoi (lit. "old word", sometimes glossed as "ragman"[3] or "antique collector"[4]) are unknown. Later traditions sometimes tied them to the Italian city of Viterbo (the Latin vetus verbum having the same meaning as the family's name) or to the Romans who immigrated east with Constantine the Great during the founding of his new capital.[4] Both were probably fabrications created to help legitimize the dynasty.[5] The family are first attested as local lords in Asia Minor, particularly Anatolikon,[4] with Nikephoros Palaiologos rising to command over Mesopotamia under Michael VII Doukas. He supported the revolt of Nikephoros III Botaneiates, while his son George married Anna Doukaina and therefore supported his sister-in-law's husband Alexios Komnenos during his rise to power.[5] As commander (doux) of Dyrrhachium, George faced the Norman Duke Robert Guiscard in battle.

The Palaiologoi held military offices and further united their family to the Doukai and Komnenoi during the 12th century.[5] They followed Theodore Laskaris to Nicaea and began to assume high-ranking political offices as well.[5] Alexios Palaiologos, whose wife was a granddaughter of Zoe Doukaina (youngest daughter of Constantine X Doukas) and her husband Adrianos Komnenos (younger brother of Emperor Alexios I). Another Alexios Palaiologos married Irene Angelina, eldest daughter of Alexios III Angelos and Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera. The latter couple's daughter Theodora Palaiologina married her cousin Andronikos Palaiologos, who was descended from Zoe. The couple were the progenitors of the imperial dynasty. Their son was Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (1223–1282).

Michael VIII's son Andronikos II Palaiologos (1259–1332) married Anne of Hungary and fathered Michael Palaiologos (1277–1320), sometimes numbered the ninth. Michael IX married Rita of Armenia. Their son, the grandson of Andronikos II, was Andronikos III Palaiologos (1297–1341).

Andronikos III married Anna of Savoy. Their son was John V Palaiologos (1332–1391). John V married Helena Kantakouzene, a daughter of his co-ruler John VI Kantakouzenos. Their sons included Andronikos IV Palaiologos (1348–1385) and Manuel II Palaiologos (1350–1425).

Manuel II married Helena Dragaš. They were the parents of John VIII Palaiologos (1392–1448) and Constantine XI Palaiologos (1404–1453), the last Byzantine emperor, as well as the despots of Morea Demetrios Palaiologos (1407–1470) and Thomas Palaiologos (1409–1465). Demetrios, after giving Mehmed II a pretext to invade Morea, was kept from his throne and remained in captivity. His daughter Helen was a member of the sultan's harem for a time. Thomas, in exile in Venice, sold the imperial title to Charles VIII of France, who however never used it for formal purposes.

Thomas' daughter Zoe (died 1503) married Ivan III of Russia and, on rejoining the Orthodox faith, returned to her earlier name Sophia. Her influence on the court curtailed the power of the boyars and eventually led to the proclamation of the Grand Prince of Muscovy as the Tsar of all the Russias. Though Thomas's male-line descendants soon became extinct, his descent lives on through a daughter and the family of Castriota Dukes of san Pietro di Galatina in south-Italian aristocracy.

Descent from Thomas to many of the current and former ruling houses of Europe comes from his descendant Charles Marie Raymond d'Arenberg. His daughter, Princess and Duchess Leopoldine d'Arenberg, married Joseph Nicholas of Windisch-Graetz, chamberlain to Archduchess Marie Antoinette of Austria. The Dukes in Bavaria descend from this line, as do the ruling houses of Belgium, Luxembourg, and Liechtenstein, and the former ruling houses of Portugal, Italy, and Romania.

Other branches of the Palaiologoi remained in Ottoman Constantinople, and even prospered in the immediate post-conquest period. In the decades after 1453, Ottoman tax registers show a consortium of noble Greeks co-operating to bid for the lucrative tax farming district including Constantinople and the ports of western Anatolia. This group included names like "Palologoz of Kassandros" and "Manuel Palologoz".[6][7] This group stood in close contact with two powerful viziers, Mesih Pasha and Hass Murad Pasha, both of whom were members of the Palaiologos family and had converted to Islam after the fall of Constantinople, as well as with other converted scions of Byzantine and Balkan aristocratic families like Mahmud Pasha Angelović, forming what the Ottomanist Halil İnalcık termed a "Greek faction" at the court of Mehmed II.[6]

Palaiologoi emperors

- Michael VIII Palaiologos

- Andronikos II Palaiologos, son of Michael VIII

- Michael IX Palaiologos, co-emperor, son of Andronikos II

- Andronikos III Palaiologos, son of Michael IX

- John V Palaiologos, son of Andronikos III (disputed by John VI Kantakouzenos, a maternal relative of the Palaiologoi)

- Andronikos IV Palaiologos, eldest son of John V

- John VII Palaiologos, son of Andronikos IV

- Andronikos V Palaiologos, co-emperor, son of John VII

- Manuel II Palaiologos, younger son of John V

- John VIII Palaiologos, eldest son of Manuel II

- Constantine XI Palaiologos, a younger son of Manuel II

Montferrat cadet branch

A younger son of Andronikos II became lord of Montferrat as heir of his mother. His feudal dynasty ruled in Montferrat, longer than the imperial branch did in Constantinople. This inheritance was eventually incorporated by marriage to the Gonzaga family, rulers of the Duchy of Mantua, who descend from the Palaiologoi of Montferrat. Later, that succession passed to the Dukes of Lorraine, whose later head became the progenitor of the Habsburg-Lorraine emperors of Austria.

The Paleologo-Oriundi, an extant line, descends from Flaminio, an illegitimate son of the last Palaiologos marquess John George.[8]

Dynastic relations

The reconstituted realm was very weak compared with the pre-1204 Empire. The Palaiologoi emperors were not granted the earlier luxury of isolation. Imperial marriages became increasingly mercenary and royal princesses regarded as little more than merchandise. The future Michael VIII married Theodora Palaiologina, a kinswoman of the Vatatzes Laskaris family, in order to solidify his position in the Nicean Empire.

Michael VIII's sister, Andronikos and Theodora's daughter Irene Palaiologina, was the mother of Maria Kantakuzenos, who married Constantine Tikh and Ivailo of Bulgaria in turn.

Michael VIII was the father of Constantine, who in turn fathered John, who became the father-in-law of Stefan Dečanski of Serbia.

Michael's daughter Irene married Ivan Asen III of Bulgaria, and another daughter, Eudokia Palaiologina, married John II Komnenos of Trebizond, and another daughter, Theodora, married David VI of Georgia.

Andronikos II Palaiologos married Anna of Hungary, daughter of Stephen V of Hungary and Elizabeth the Cuman. They were parents of Michael IX Palaiologos, who predeceased his father but was a co-regent, as such sometimes numbered the ninth. This Michael married Rita of Armenia, a princess of Cilician Armenia as daughter of Leo III of Armenia and Queen Keran of Armenia.

His son, the grandson of Andronikos II, was Andronikos III Palaiologos. Michael's daughter Theodora Palaiologina married Theodore Svetoslav and Michael Shishman, rulers of Bulgaria, in turn. A daughter Anna Palaiologina married first Thomas I Komnenos Doukas, Ruler of Epirus and then his successor Nicholas Orsini, already count of Kefalonia.

By his second wife, Irene of Montferrat, Andronikos II had Simonis, later the wife of Stefan Milutin of Serbia. His son, Theodore I, Marquess of Montferrat, became lord of Montferrat as heir of his mother. Theodore' inheritance was eventually incorporated by marriage to the Gonzaga family, rulers of the Duchy of Mantua.

Andronikos III married firstly Irene of Brunswick, who died without surviving issue, and secondly Anna of Savoy who was descended from Baldwin I of Constantinople. They were the parents of John V Palaiologos. John V was compelled to marry Helena Kantakouzene, a daughter of John VI Kantakouzenos.

In order to obtain support to remove John VI, John V gave his sister Maria to Francesco I Gattilusio, who received the lordship of Lesbos, an island which remained under the control of the Genoese until the Ottoman conquest of Lesbos in 1462. They founded the noble family who continued into Italian Genoese aristocracy, being ancestors of the princes of Monaco.

Andronikos IV Palaiologos married Keratsa of Bulgaria. She was a daughter of Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria.

Manuel II Palaiologos married Helena Dragaš, daughter of Constantine Dragaš who was a regional lord of the dissolved Serbian realm.

Thomas Palaiologos' daughter Zoe married Ivan III of Russia.

In 1446, Zoe's elder sister Helena Palaiologina was married to Lazar Branković, a Serbian prince. Their descendants continued for some time in the Balkans. Thomas's male-line descendants shortly became extinct.

Political history

Under the rule of the Palaiologoi (1261 - 1453), the fragmented Byzantine Empire still considered themselves to be the Roman Empire, but began to focus more on the empire's Greek heritage. The word "Hellene" began to be used again to describe themselves, after having been a synonym for "pagan" for many centuries. The dynasty was a patron of literature and the arts; among others, George Gemistos Plethon came to prominence. The hesychasm controversy also took place during the rule of the Palaiologoi dynasty.

At the later days of their empire the Peloponnese was the largest and wealthiest part of the empire, and was ruled as the Despotate of Morea by members of the Palaiologos family, often two or three younger brothers simultaneously. Although they often squabbled amongst themselves they were usually fiercely loyal to the emperor in Constantinople (though sometimes they sought to supplant the emperor and rise to the throne), while their land was surrounded by hostile Venetians and Turks. The capital of the despotate was Mystras, a large fortress built by the Palaiologoi near Sparta.

The Palaiologoi frequently attempted to reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church, hoping this would lead the West to give them aid against the Turks. Template:Itation needed

The family had connections throughout Europe. They married into the Bulgarian, Georgian and Serbian royal families, as well as the noble families of Trebizond, Epirus, the Republic of Genoa, Montferrat, and Muscovy.

See also

- Paul Palaiologos Tagaris (c. 1320/40 – after 1394), monk and religious impostor, Latin patriarch of Constantinople, claimed spurious kinship to the Palaiologoi

- Jacob Palaeologus (c. 1520 – 1585), reformist theologian, claimed spurious kinship to the Palaiologoi

References

- 1 2 Vasiliev, Aleksandr A. (1964). History of the Byzantine Empire. 2. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 583. ISBN 9780299809263.

The dynasty of the Palaeologi belonged to a very well known Greek family which, beginning with the first Comneni, gave Byzantium many energetic and gifted men, especially in the military field.

- ↑ Gill, Joseph (1980). "Family feuds in fourteenth century Byzantium: Palaeologi and Cantacuzeni". Conspectus of History. Ball State University. 1 (5): 64.

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander P. (1991). "Palaiologos". Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. III. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1557. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001. ISBN 9780195046526.

- 1 2 3 Vannier, Jean-François (1986). "Les premiers Paléologues. Étude généalogique et prosopographique". In Cheynet, Jean-Claude. Études prosopographiques. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. p. 129. ISBN 9782859441104.

- 1 2 3 4 "Palaeologan Dynasty (1259-1453)". Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World. Asia Minor: Foundation of the Hellenic World. 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 Papademetriou 2015, p. 190.

- ↑ Vryonis, Speros (1969). "The Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman Forms". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. 23/24: 251–308. doi:10.2307/1291294. JSTOR 1291294. OCLC 31601728.

- ↑ Cassano, Gian Paolo (July 2017). "Organo di informazione del Circolo Culturale "I Marchesi del Monferrato" "in attesa di registrazione in Tribunale"" (PDF). Bollettino del Marchesato. Cassa di Risparmio di Alessandria. 3 (16): 3–9. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

Sources

- Papademetriou, Tom (2015). Render Unto the Sultan: Power, Authority, and the Greek Orthodox Church in the Early Ottoman Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871789-8.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Palaeologus. |

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy of the Palaiologos dynasty from Genealogy.eu". Genealogy.EU.

— Imperial house — Palaiologos dynasty Founding year: 11th century | ||

| Preceded by Laskaris dynasty |

Ruling house of the Byzantine Empire 1 January 1259 – 29 May 1453 |

Succeeded by Ottoman dynasty |