Mid-ocean ridge

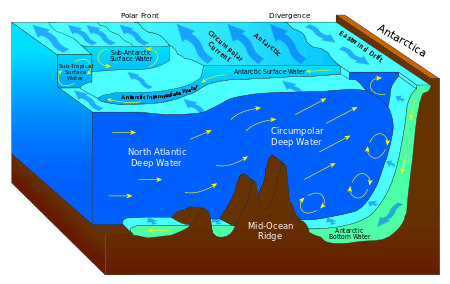

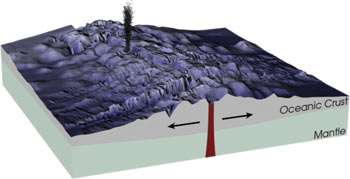

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is an underwater mountain system formed by plate tectonics.[1] It consists of various mountains linked in chains, typically having a valley known as a rift running along its spine. This type of oceanic mountain ridge is characteristic of what is known as an 'oceanic spreading center', which is responsible for seafloor spreading.[2] The production of new seafloor results from mantle upwelling in response to plate spreading; this isentropic upwelling solid mantle material eventually exceeds the solidus and melts. The buoyant melt rises as magma at a linear weakness in the oceanic crust, and emerges as lava, creating new crust upon cooling. A mid-ocean ridge demarcates the boundary between two tectonic plates, and consequently is termed a divergent plate boundary.

Description

.jpg)

Volcanism

Mid-ocean ridges are geologically active, with continuing volcanism and seismicity. New magma steadily emerges onto the ocean floor and intrudes into the ocean crust at and near rifts along the ridge axes. The crystallized magma forms new crust of basalt (known as MORB for mid-ocean ridge basalt) and below it (in the lower oceanic crust), gabbro.[3] MORs are formed by two oceanic plates moving away from each other. Hydrothermal vents are a common feature at oceanic spreading centers.[4]

The rocks making up the crust below the seafloor are youngest along the axis of the ridge and age with increasing distance from that axis. New magma of basalt composition emerges at and near the axis because of decompression melting in the underlying Earth's mantle.[5]

The oceanic crust is made up of rocks much younger than the Earth itself. Most oceanic crust in the ocean basins is less than 200 million years old. The crust is in a constant state of "renewal" at the ocean ridges. Moving away from the mid-ocean ridge, ocean depth progressively increases; the greatest depths are in ocean trenches. As the oceanic crust moves away from the ridge axis, the peridotite in the underlying mantle cools and becomes more rigid. The crust and the relatively rigid peridotite below it make up the oceanic lithosphere.

Morphology

The bathymetry, or profile of a MOR is largely determined by the seafloor spreading rate at the ridge.[6] Slow spreading ridges (< 5 cm/yr) like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR) generally have large, wide rift valleys, sometimes as wide as 10–20 km (6.2–12.4 mi), and very rugged terrain at the ridge crest that can have relief of up to a 1,000 m (3,300 ft). By contrast, fast spreading ridges (>8 cm/yr) like the East Pacific Rise (EPR) are narrow, sharp incisions surrounded by generally flat topography that slopes away from the ridge over many hundreds of miles.[6] Ultra-slow spreading ridges (< 2 cm/yr), like the Southwest India and the Arctic Ridges form both magmatic and amagmatic ridge segments without transform faults.[7]

The spreading center or axis, commonly connects to a transform fault oriented at right angles to the axis. The flanks of mid-ocean ridges are in many places marked by the inactive scars of transform faults called fracture zones. At faster spreading rates the axes often display Overlapping Spreading Centers that lack connecting transform faults.[8]

The depth of the seafloor (or the height of a location on a mid-ocean ridge above a baselevel) is closely correlated with its age (age of the lithosphere where depth is measured). The age-depth relation can be modeled by the cooling of a lithosphere plate[9][10] or mantle half-space[11] in areas without significant subduction. The overall shape of ridges results from Pratt isostacy: close to the ridge axis there is hot, low-density mantle supporting the oceanic crust. As the oceanic plates cool, away from the ridge axes, the oceanic mantle lithosphere (the colder, denser part of the mantle that, together with the crust, comprises the oceanic plates) thickens and the density increases. Thus older seafloor is underlain by denser material and is deeper. The width of the ridge is hence a function of spreading rate – slow ridges like the MAR have spread much less far (showing a narrower profile) than faster ridges like the EPR (wider profile) for the same amount of cooling and consequent bathymetric deepening.

Formation processes

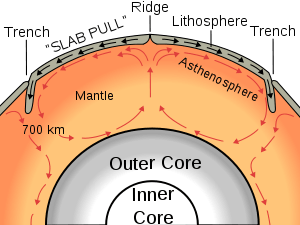

Two processes, ridge-push and slab pull, are thought to be responsible for the spreading seen at mid-ocean ridges, and there is some uncertainty as to which is dominant. Ridge-push occurs when the growing bulk of the ridge pushes the rest of the tectonic plate away from the ridge, often towards a subduction zone. At the subduction zone, "slab-pull" comes into effect. This is simply the weight of the tectonic plate being subducted (pulled) below the overlying plate dragging the rest of the plate along behind it. The slab pull mechanism is considered to be contributing more than the ridge push.[12]

The other process proposed to contribute to the formation of new oceanic crust at mid-ocean ridges is the "mantle conveyor" (see image). However, there have been some studies which have shown that the upper mantle (asthenosphere) is too plastic (flexible) to generate enough friction to pull the tectonic plate along. Moreover, unlike in the image above, mantle upwelling that causes magma to form beneath the ocean ridges appears to involve only its upper 400 km (250 mi), as deduced from seismic tomography and from studies of the seismic discontinuity at about 400 km (250 mi). The relatively shallow depths from which the upwelling mantle rises below ridges are more consistent with the "slab-pull" process. On the other hand, some of the world's largest tectonic plates such as the North American Plate are in motion, yet are nowhere being subducted.

The rate at which the mid-ocean ridge creates new material is known as the spreading rate, and is typically measured in mm/yr. As a general rule, fast ridges have spreading (opening) rates of more than 90 mm/year. Intermediate ridges have a spreading rate of 50–90 mm/year while slow spreading ridges have a rate less than 50 mm/year.[6][13]:2 The spreading rate of the North Atlantic Ocean is ~ 25 mm/yr, while in the Pacific region, it is 80–120 mm/yr. Ridges that spread at rates <20 mm/yr are referred to as ultraslow spreading ridges[13]:2 (e.g., the Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean and the Southwest Indian Ridge) and they provide a much different perspective on crustal formation than their faster spreading brethren.

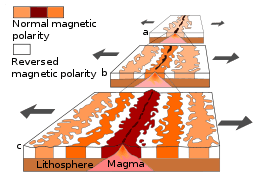

The mid-ocean ridge systems form new oceanic crust. As crystallized basalt extruded at a ridge axis cools below Curie points of appropriate iron-titanium oxides, magnetic field directions parallel to the Earth's magnetic field are recorded in those oxides. The orientations of the field in the oceanic crust preserve a record of directions of the Earth's magnetic field with time. Because the field has reversed directions at irregular intervals throughout its history, the pattern of geomagnetic reversals in the ocean crust can be used as an indicator of age.[14] Likewise, the pattern of reversals together with age measurements of the crust is used to help establish the history of the Earth's magnetic field.

Global system

The mid-ocean ridges of the world are connected and form the Ocean Ridge, a single global mid-oceanic ridge system that is part of every ocean, making it the longest mountain range in the world. The continuous mountain range is 65,000 km (40,400 mi) long (several times longer than the Andes, the longest continental mountain range), and the total length of the oceanic ridge system is 80,000 km (49,700 mi) long.[15]

Increased rates of sea-floor spreading (i.e. the expansion of the mid-ocean ridge) has caused global (eustatic) sea-level to rise over very long timescales (millions of years).[16]

The high sea levels that occurred during the Cretaceous period (144–65 Ma) can only be attributed to plate tectonics since thermal expansion and the absence of ice sheets by themselves cannot account for the fact that sea levels were 100–170 meters higher than today.[17]

Increased sea-floor spreading means that the hot young crust at the mid-ocean ridge will form at a faster rate than it can be destroyed at subduction zones. The mid-ocean ridge will then expand and form a broader ridge, taking up more space in the ocean basin and causing sea levels to rise.[17]

Sea-level change can be attributed to other factors (thermal expansion, ice melting). Over very long timescales, however, it is the result of changes in the volume of the ocean basins which are, in turn, affected by rates of sea-floor spreading along the mid-ocean ridges.[18]

Seawater Chemistry

Mid-ocean ridges are global scale ion-exchange systems.[19]

Rapid spreading rates will expand the mid-ocean ridge causing basalt reactions with seawater to happen faster. The magnesium/calcium ratio will be lower because more magnesium ions are being removed from seawater and consumed by the rock, and more calcium ions are being removed from the rock and released to seawater. A lower Mg/Ca ratio favors the precipitation of low-Mg calcite polymorphs of calcium carbonate (calcite seas).[19]

Slow spreading at mid-ocean ridges has the opposite effect and will result in a higher Mg/Ca ratio favoring the precipitation of aragonite and high-Mg calcite polymorphs of calcium carbonate (aragonite seas).[19]

Experiments show that most modern high-Mg calcite organisms would have been low-Mg calcite in past calcite seas,[20] meaning that the Mg/Ca ratio in an organism's skeleton varies with the Mg/Ca ratio of the seawater in which it was grown.

The mineralogy of reef-building and sediment-producing organisms is thus regulated by chemical reactions occurring along the mid-ocean ridge, the rate of which is controlled by sea-floor spreading.[20]

History

Discovery

Mid-ocean ridges are generally submerged deep in the ocean. It was not until the 1950s, when the ocean floor was surveyed in detail, that their full extent became known.

The Vema, a ship of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, traversed the Atlantic Ocean, recording data about the ocean floor from the ocean surface. A team led by Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen analyzed the data and concluded that there was an enormous mountain chain running up the middle. Scientists named it the "Mid-Atlantic Ridge".

At first, the ridge was thought to be a phenomenon specific to the Atlantic Ocean. However, as surveys of the ocean floor continued around the world, it was discovered that every ocean contains parts of the mid-ocean ridge system. Although the ridge system runs down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the ridge is located away from the center of other oceans.

Impact

Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift in 1912. He stated: "the Mid-Atlantic Ridge ... zone in which the floor of the Atlantic, as it keeps spreading, is continuously tearing open and making space for fresh, relatively fluid and hot sima [rising] from depth".[21] However, Wegener did not pursue this observation in his later works and his theory was dismissed by geologists because there was no mechanism to explain how continents could plow through ocean crust, and the theory became largely forgotten.

Following the discovery of the worldwide extent of the mid-ocean ridge in the 1950s, geologists faced a new task: explaining how such an enormous geological structure could have formed. In the 1960s, geologists discovered and began to propose mechanisms for seafloor spreading. The discovery of mid-ocean ridges and the process of seafloor spreading allowed for Wegner's theory to be expanded so that it included the movement of oceanic crust as well as the continents.[22] Plate tectonics was a suitable explanation for seafloor spreading, and the acceptance of plate tectonics by the majority of geologists resulted in a major paradigm shift in geological thinking.

It is estimated that 20 volcanic eruptions occur each year along earth's mid-ocean ridges and that every year 2.5 km2 (0.97 sq mi) of new seafloor is formed by this process. With a crustal thickness of 1 to 2 km (0.62 to 1.24 mi), this amounts to about 4 km3 (0.96 cu mi) of new ocean crust formed every year.

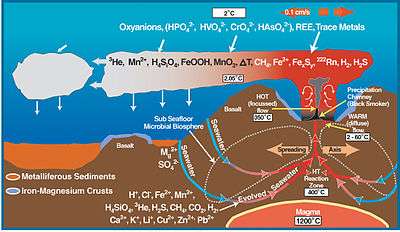

Oceanic ridge and deep sea vent chemistry

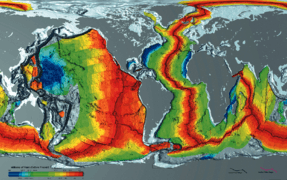

Oceanic ridge and deep sea vent chemistry Age of oceanic crust. The red is most recent, and blue is the oldest.

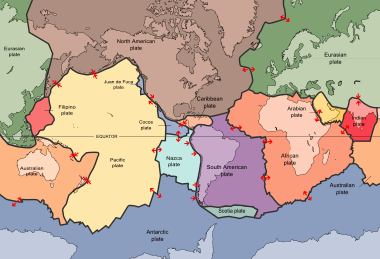

Age of oceanic crust. The red is most recent, and blue is the oldest. Plates in the crust of the earth, according to the plate tectonics theory

Plates in the crust of the earth, according to the plate tectonics theory Seafloor magnetic striping

Seafloor magnetic striping A demonstration of magnetic striping

A demonstration of magnetic striping

List of oceanic ridges

- Aden Ridge

- Cocos Ridge

- Explorer Ridge

- Gorda Ridge

- Juan de Fuca Ridge

- American-Antarctic Ridge

- Chile Rise

- East Pacific Rise

- East Scotia Ridge

- Gakkel Ridge (Mid-Arctic Ridge)

- Nazca Ridge

- Pacific-Antarctic Ridge

- Central Indian Ridge

- Southeast Indian Ridge

- Southwest Indian Ridge

- Mid-Atlantic Ridge

- Kolbeinsey Ridge (North of Iceland)

- Mohns Ridge

- Knipovich Ridge (between Greenland and Spitsbergen)

- Reykjanes Ridge (South of Iceland)

List of ancient oceanic ridges

See also

References

- ↑ Searle,, Roger (2013). Mid-ocean ridges. New York: Cambridge. ISBN 9781107017528. OCLC 842323181.

- ↑ Faulting and Magmatism at Mid‐Ocean Ridges | Geophysical Monograph Series. Bibcode:1998GMS...106.....R. doi:10.1029/gm106.

- ↑ Michael, Peter; Cheadle, Michael (February 20, 2009). "Making a Crust". Science. 323: 1017–18. doi:10.1126/science.1169556.

- ↑ Martin, William; Baross, John; Kelley, Deborah; Russell, Michael J. (2008-11-01). "Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 6 (11): 805–814. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1991. ISSN 1740-1526.

- ↑ Marjorie Wilson (1993). Igneous petrogenesis. London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-53310-5.

- 1 2 3 Macdonald, K. C. (1982). "Mid-Ocean Ridges: Fine Scale Tectonic, Volcanic and Hydrothermal Processes Within the Plate Boundary Zone". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 10 (1): 155–190. Bibcode:1982AREPS..10..155M. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.10.050182.001103.

- ↑ Dick, Henry J. B.; Lin, Jian; Schouten, Hans (November 2003). "An ultraslow-spreading class of ocean ridge". Nature. 426 (6965): 405–412. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..405D. doi:10.1038/nature02128. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ↑ Macdonald, Ken C.; Fox, P. J. (1983). "Overlapping spreading centres: new accretion geometry on the East Pacific Rise". Nature. 302 (5903): 55–58. Bibcode:1983Natur.302...55M. doi:10.1038/302055a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ↑ Sclater, John G.; Anderson, Roger N.; Bell, M. Lee (1971-11-10). "Elevation of ridges and evolution of the central eastern Pacific". Journal of Geophysical Research. 76 (32): 7888–7915. Bibcode:1971JGR....76.7888S. doi:10.1029/jb076i032p07888. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ Parsons, Barry; Sclater, John G. (1977-02-10). "An analysis of the variation of ocean floor bathymetry and heat flow with age". Journal of Geophysical Research. 82 (5): 803–827. Bibcode:1977JGR....82..803P. doi:10.1029/jb082i005p00803. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ Davis, E.E; Lister, C. R. B. (1974). "Fundamentals of Ridge Crest Topography". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. North-Holland Publishing Company. 21: 405–413. Bibcode:1974E&PSL..21..405D. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(74)90180-0.

- ↑ Harff, Jan; Meschede, Martin; Petersen, Sven; Thiede, Jörn. Driving Forces: Slab Pull, Ridge Push (2014 ed.). Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6644-0_105-1. ISBN 978-94-007-6644-0.

- 1 2 Searle, Roger (2013). Mid-ocean ridges. New York: Cambridge. p. 2. ISBN 9781107017528. OCLC 842323181.

- ↑ Puetz, Stephen; et al. (January 2017). "Quantifying the evolution of the continental and oceanic crust". Earth-Science Reviews. 164: 63–83. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.10.011.

- ↑ "What is the longest mountain range on earth?". Ocean Facts. NOAA. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ Church, J.A.; Gregory, J.M. Sea Level Change. pp. 2599–2604. doi:10.1006/rwos.2001.0268.

- 1 2 Miller, Kenneth G. (2009). Encyclopedia of Paleoclimatology and Ancient Environments. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 879–887. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4411-3_206.

- ↑ Kominz, M.A. Sea Level Variations Over Geologic Time. pp. 2605–2613. doi:10.1006/rwos.2001.0255.

- 1 2 3 Hardie, Lawrence; Stanley, Steven (February 1999). "Hypercalcification: Paleontology Links Plate Tectonics and Geochemistry to Sedimentology" (PDF). GSA Today. 9 (2): 1–7.

- 1 2 Ries, Justin B. (2004-11-01). "Effect of ambient Mg/Ca ratio on Mg fractionation in calcareous marine invertebrates: A record of the oceanic Mg/Ca ratio over the Phanerozoic". Geology. 32 (11). Bibcode:2004Geo....32..981R. doi:10.1130/g20851.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Jacoby, W. R. (January 1981). "Modern concepts of earth dynamics anticipated by Alfred Wegener in 1912". Geology. 9: 25–27. Bibcode:1981Geo.....9...25J. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1981)9<25:MCOEDA>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Society, National Geographic (2015-06-08). "seafloor spreading". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2017-04-14.