Seafloor spreading

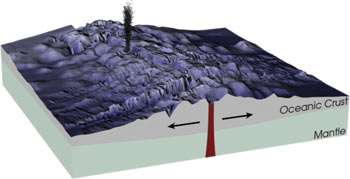

Seafloor spreading is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories (e.g. by Alfred Wegener and Alexander du Toit) of continental drift postulated that continents "ploughed" through the sea. The idea that the seafloor itself moves (and also carries the continents with it) as it expands from a central axis was proposed by Harry Hess from Princeton University in the 1960s.[1] The theory is well accepted now, and the phenomenon is known to be caused by convection currents in the asthenosphere, which is ductile, or plastic, and the brittle lithosphere (crust and upper mantle).[2]

Significance

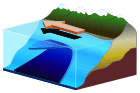

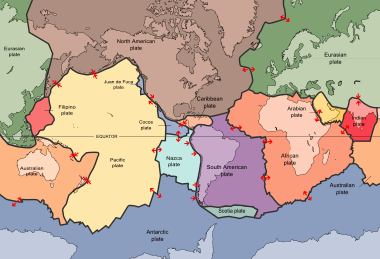

Seafloor spreading helps explain continental drift in the theory of plate tectonics. When oceanic plates diverge, tensional stress causes fractures to occur in the lithosphere. The motivating force for seafloor spreading ridges is tectonic plate pull rather than magma pressure, although there is typically significant magma activity at spreading ridges.[3] At a spreading center, basaltic magma rises up the fractures and cools on the ocean floor to form new seabed. Hydrothermal vents are common at spreading centers. Older rocks will be found farther away from the spreading zone while younger rocks will be found nearer to the spreading zone. Additionally spreading rates determine if the ridge is a fast, intermediate, or slow. As a general rule, fast ridges have spreading (opening) rates of more than 9 cm/year. Intermediate ridges have a spreading rate of 5–9 cm/year while slow spreading ridges have a rate less than 5 cm/year.[4][5]:2

Spreading center

Seafloor spreading occurs at spreading centers, distributed along the crests of mid-ocean ridges. Spreading centers end in transform faults or in overlapping spreading center offsets. A spreading center includes a seismically active plate boundary zone a few kilometers to tens of kilometers wide, a crustal accretion zone within the boundary zone where the ocean crust is youngest, and an instantaneous plate boundary - a line within the crustal accretion zone demarcating the two separating plates.[6] Within the crustal accretion zone is a 1-2 km-wide neovolcanic zone where active volcanism occurs.[7][8]

Incipient spreading

In the general case, sea floor spreading starts as a rift in a continental land mass, similar to the Red Sea-East Africa Rift System today.[9] The process starts by heating at the base of the continental crust which causes it to become more plastic and less dense. Because less dense objects rise in relation to denser objects, the area being heated becomes a broad dome (see isostasy). As the crust bows upward, fractures occur that gradually grow into rifts. The typical rift system consists of three rift arms at approximately 120 degree angles. These areas are named triple junctions and can be found in several places across the world today. The separated margins of the continents evolve to form passive margins. Hess' theory was that new seafloor is formed when magma is forced upward toward the surface at a mid-ocean ridge.

If spreading continues past the incipient stage described above, two of the rift arms will open while the third arm stops opening and becomes a 'failed rift'. As the two active rifts continue to open, eventually the continental crust is attenuated as far as it will stretch. At this point basaltic oceanic crust begins to form between the separating continental fragments. When one of the rifts opens into the existing ocean, the rift system is flooded with seawater and becomes a new sea. The Red Sea is an example of a new arm of the sea. The East African rift was thought to be a "failed" arm that was opening somewhat more slowly than the other two arms, but in 2005 the Ethiopian Afar Geophysical Lithospheric Experiment[10] reported that in the Afar region, September 2005, a 60 km fissure opened as wide as eight meters.[11] During this period of initial flooding the new sea is sensitive to changes in climate and eustasy. As a result, the new sea will evaporate (partially or completely) several times before the elevation of the rift valley has been lowered to the point that the sea becomes stable. During this period of evaporation large evaporite deposits will be made in the rift valley. Later these deposits have the potential to become hydrocarbon seals and are of particular interest to petroleum geologists.

Sea floor spreading can stop during the process, but if it continues to the point that the continent is completely severed, then a new ocean basin is created. The Red Sea has not yet completely split Arabia from Africa, but a similar feature can be found on the other side of Africa that has broken completely free. South America once fit into the area of the Niger Delta. The Niger River has formed in the failed rift arm of the triple junction.

Continued spreading and subduction

As new seafloor forms and spreads apart from the mid-ocean ridge it slowly cools over time. Older seafloor is therefore colder than new seafloor, and older oceanic basins deeper than new oceanic basins due to isostasy. If the diameter of the earth remains relatively constant despite the production of new crust, a mechanism must exist by which crust is also destroyed. The destruction of oceanic crust occurs at subduction zones where oceanic crust is forced under either continental crust or oceanic crust. Today, the Atlantic basin is actively spreading at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Only a small portion of the oceanic crust produced in the Atlantic is subducted. However, the plates making up the Pacific Ocean are experiencing subduction along many of their boundaries which causes the volcanic activity in what has been termed the Ring of Fire of the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific is also home to one of the world's most active spreading centers (the East Pacific Rise) with spreading rates of up to 13 cm/yr. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a "textbook" slow-spreading center, while the East Pacific Rise is used as an example of fast spreading. Spreading centers at slow and intermediate rates exhibit a rift valley while at fast rates an axial high is found within the crustal accretion zone.[4] The differences in spreading rates affect not only the geometries of the ridges but also the geochemistry of the basalts that are produced.[12]

Since the new oceanic basins are shallower than the old oceanic basins, the total capacity of the world's ocean basins decreases during times of active sea floor spreading. During the opening of the Atlantic Ocean, sea level was so high that a Western Interior Seaway formed across North America from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean.

Debate and search for mechanism

At the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (and in other areas), material from the upper mantle rises through the faults between oceanic plates to form new crust as the plates move away from each other, a phenomenon first observed as continental drift. When Alfred Wegener first presented a hypothesis of continental drift in 1912, he suggested that continents ploughed through the ocean crust. This was impossible: oceanic crust is both more dense and more rigid than continental crust. Accordingly, Wegener's theory wasn't taken very seriously, especially in the United States.

Since then, it has been shown that the motion of the continents is linked to seafloor spreading by the theory of plate tectonics. In the 1960s, the past record of geomagnetic reversals was noticed by observing the magnetic stripe "anomalies" on the ocean floor.[13] This results in broadly evident "stripes" from which the past magnetic field polarity can be inferred by looking at the data gathered from simply towing a magnetometer on the sea surface or from an aircraft. The stripes on one side of the mid-ocean ridge were the mirror image of those on the other side. The seafloor must have originated on the Earth's great fiery welts, like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the East Pacific Rise.

The driver for seafloor spreading in plates with active margins is the weight of the cool, dense, subducting slabs that pull them along. The magmatism at the ridge is considered to be "passive upswelling", which is caused by the plates being pulled apart under the weight of their own slabs.[14][15] This can be thought of as analogous to a rug on a table with little friction: when part of the rug is off of the table, its weight pulls the rest of the rug down with it.

Sea floor global topography: half-space model

The depth of the seafloor (or the height of a location on a mid-ocean ridge above a baselevel) is closely correlated with its age (age of the lithosphere where depth is measured). The age-depth relation can be modeled by the cooling of a lithosphere plate[16][17] or mantle half-space in areas without significant subduction.[18]

In the half-space model,[18] the seabed height is determined by the oceanic lithosphere temperature, due to thermal expansion. Oceanic lithosphere is continuously formed at a constant rate at the mid-ocean ridges. The source of the lithosphere has a half-plane shape (x = 0, z < 0) and a constant temperature T1. Due to its continuous creation, the lithosphere at x > 0 is moving away from the ridge at a constant velocity v, which is assumed large compared to other typical scales in the problem. The temperature at the upper boundary of the lithosphere (z=0) is a constant T0 = 0. Thus at x = 0 the temperature is the Heaviside step function . Finally, we assume the system is at a quasi-steady state, so that the temperature distribution is constant in time, i.e. T=T(x,z).

By calculating in the frame of reference of the moving lithosphere (velocity v), which have spatial coordinate x' = x-vt, we may write T = T(x',z,t) and use the heat equation: where is the thermal diffusivity of the mantle lithosphere.

Since T depends on x' and t only through the combination , we have:

Thus:

We now use the assumption that is large compared to other scales in the problem; we therefore neglect the last term in the equation, and get a 1-dimensional diffusion equation: with the initial conditions .

The solution for is given by the error function :

- .

Due to the large velocity, the temperature dependence on the horizontal direction is negligible, and the height at time t (i.e. of sea floor of age t) can be calculated by integrating the thermal expansion over z:

where is the effective volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, and h0 is the mid-ocean ridge height (compared to some reference).

Note that the assumption the v is relatively large is equivalently to the assumption that the thermal diffusivity is small compared to , where L is the ocean width (from mid-ocean ridges to continental shelf) and T is its age.

The effective thermal expansion coefficient is different from the usual thermal expansion coefficient due to isostasic effect of the change in water column height above the lithosphere as it expands or retracts. Both coefficients are related by:

where is the rock density and is the density of water.

By substituting the parameters by their rough estimates: m2/s, °C−1 and T1 ~1220 °C (for the Atlantic and Indian oceans) or ~1120 °C (for the eastern Pacific), we have:

for the eastern Pacific Ocean, and:

for the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, where the height is in meters and time is in millions of years. To get the dependence on x, one must substitute t = x/v ~ Tx/L, where L is the distance between the ridge to the continental shelf (roughly half the ocean width), and T is the ocean age.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seafloor spreading. |

References

- ↑ Hess, H. H. (November 1962). "History of Ocean Basins" (PDF). In A. E. J. Engel; Harold L. James; B. F. Leonard. Petrologic studies: a volume to honor A. F. Buddington. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America. pp. 599–620. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ Elsasser, Walter M. (1971). "Sea-Floor Spreading as Thermal Convection". Journal of Geophysical Research. 76 (5): 1101. Bibcode:1971JGR....76.1101E. doi:10.1029/JB076i005p01101.

- ↑ Tan, Yen Joe; Tolstoy, Maya; Waldhauser, Felix; Wilcock, William S. D. (2016). "Dynamics of a seafloor-spreading episode at the East Pacific Rise". Nature. 540 (7632): 261–265. Bibcode:2016Natur.540..261T. doi:10.1038/nature20116. PMID 27842380.

- 1 2 Macdonald, K. C. (1982). "Mid-Ocean Ridges: Fine Scale Tectonic, Volcanic and Hydrothermal Processes Within the Plate Boundary Zone". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 10 (1): 155–190. Bibcode:1982AREPS..10..155M. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.10.050182.001103.

- ↑ Searle, Roger (2013). Mid-ocean ridges. New York: Cambridge. ISBN 9781107017528. OCLC 842323181.

- ↑ Luyendyk, Bruce P.; Macdonald, Ken C. (1976-06-01). "Spreading center terms and concepts". Geology. 4 (6): 369. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1976)4<369:sctac>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Daignieres, Marc; Courtillot, Vincent; Bayer, Roger; Tapponnier, Paul (1975). "A model for the evolution of the axial zone of mid-ocean ridges as suggested by icelandic tectonics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 26 (2): 222–232. Bibcode:1975E&PSL..26..222D. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(75)90089-8.

- ↑ McClinton, J. Timothy; White, Scott M. (2015-03-01). "Emplacement of submarine lava flow fields: A geomorphological model from the Niños eruption at the Galápagos Spreading Center". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 16 (3): 899–911. Bibcode:2015GGG....16..899M. doi:10.1002/2014gc005632. ISSN 1525-2027.

- ↑ Makris, J.; Ginzburg, A. (1987-09-15). "Sedimentary basins within the Dead Sea and other rift zones The Afar Depression: transition between continental rifting and sea-floor spreading". Tectonophysics. 141 (1): 199–214. Bibcode:1987Tectp.141..199M. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(87)90186-7.

- ↑ Bastow, Ian D.; Keir, Derek; Daly, Eve (2011-06-01). "The Ethiopia Afar Geoscientific Lithospheric Experiment (EAGLE): Probing the transition from continental rifting to incipient seafloor spreading". Geological Society of America Special Papers. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 478: 51–76. doi:10.1130/2011.2478(04). ISBN 978-0-8137-2478-2. ISSN 0072-1077.

- ↑ Grandin, R.; Socquet, A.; Binet, R.; Klinger, Y.; Jacques, E.; Chabalier, J.-B. de; King, G. C. P.; Lasserre, C.; Tait, S. (2009-08-01). "September 2005 Manda Hararo-Dabbahu rifting event, Afar (Ethiopia): Constraints provided by geodetic data". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (B8). Bibcode:2009JGRB..114.8404G. doi:10.1029/2008jb005843. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ Bhagwat, S.B. (2009). Foundation of Geology Vol 1. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 83. ISBN 9788182202764.

- ↑ Vine, F. J.; Matthews, D. H. (1963). "Magnetic Anomalies Over Oceanic Ridges". Nature. 199 (4897): 947–949. Bibcode:1963Natur.199..947V. doi:10.1038/199947a0.

- ↑ Forsyth, Donald; Uyeda, Seiya (1975-10-01). "On the Relative Importance of the Driving Forces of Plate Motion". Geophysical Journal International. 43 (1): 163–200. Bibcode:1975GeoJ...43..163F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1975.tb00631.x. ISSN 0956-540X.

- ↑ Patriat, Philippe; Achache, José (1984). "India–Eurasia collision chronology has implications for crustal shortening and driving mechanism of plates". Nature. 311 (5987): 615. Bibcode:1984Natur.311..615P. doi:10.1038/311615a0.

- ↑ Sclater, John G.; Anderson, Roger N.; Bell, M. Lee (1971-11-10). "Elevation of ridges and evolution of the central eastern Pacific". Journal of Geophysical Research. 76 (32): 7888–7915. Bibcode:1971JGR....76.7888S. doi:10.1029/jb076i032p07888. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ Parsons, Barry; Sclater, John G. (1977-02-10). "An analysis of the variation of ocean floor bathymetry and heat flow with age". Journal of Geophysical Research. 82 (5): 803–827. Bibcode:1977JGR....82..803P. doi:10.1029/jb082i005p00803. ISSN 2156-2202.

- 1 2 Davis, E.E; Lister, C. R. B. (1974). "Fundamentals of Ridge Crest Topography". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. North-Holland Publishing Company. 21 (4): 405–413. Bibcode:1974E&PSL..21..405D. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(74)90180-0.

External links

| The Wikibook Historical Geology has a page on the topic of: Seafloor spreading |