Tidal power

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

| Part of a series about |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

| Energy conservation |

| Renewable energy |

| Sustainable transport |

|

Tidal power or tidal energy is a form of hydropower that converts the energy obtained from tides into useful forms of power, mainly electricity.

Although not yet widely used, tidal energy has potential for future electricity generation. Tides are more predictable than the wind and the sun. Among sources of renewable energy, tidal energy has traditionally suffered from relatively high cost and limited availability of sites with sufficiently high tidal ranges or flow velocities, thus constricting its total availability. However, many recent technological developments and improvements, both in design (e.g. dynamic tidal power, tidal lagoons) and turbine technology (e.g. new axial turbines, cross flow turbines), indicate that the total availability of tidal power may be much higher than previously assumed, and that economic and environmental costs may be brought down to competitive levels.

Historically, tide mills have been used both in Europe and on the Atlantic coast of North America. The incoming water was contained in large storage ponds, and as the tide went out, it turned waterwheels that used the mechanical power it produced to mill grain.[1] The earliest occurrences date from the Middle Ages, or even from Roman times.[2][3] The process of using falling water and spinning turbines to create electricity was introduced in the U.S. and Europe in the 19th century.[4]

The world's first large-scale tidal power plant was the Rance Tidal Power Station in France, which became operational in 1966. It was the largest tidal power station in terms of output until Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station opened in South Korea in August 2011. The Sihwa station uses sea wall defense barriers complete with 10 turbines generating 254 MW.[5]

Generation of tidal energy

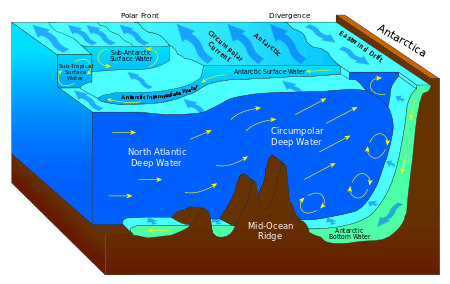

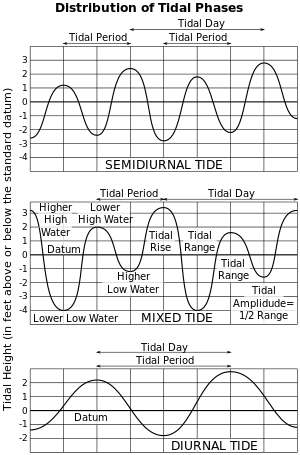

Tidal power is taken from the Earth's oceanic tides. Tidal forces are periodic variations in gravitational attraction exerted by celestial bodies. These forces create corresponding motions or currents in the world's oceans. Due to the strong attraction to the oceans, a bulge in the water level is created, causing a temporary increase in sea level. As the Earth rotates, this bulge of ocean water meets the shallow water adjacent to the shoreline and creates a tide. This occurrence takes place in an unfailing manner, due to the consistent pattern of the moon’s orbit around the earth.[6] The magnitude and character of this motion reflects the changing positions of the Moon and Sun relative to the Earth, the effects of Earth's rotation, and local geography of the sea floor and coastlines.

Tidal power is the only technology that draws on energy inherent in the orbital characteristics of the Earth–Moon system, and to a lesser extent in the Earth–Sun system. Other natural energies exploited by human technology originate directly or indirectly with the Sun, including fossil fuel, conventional hydroelectric, wind, biofuel, wave and solar energy. Nuclear energy makes use of Earth's mineral deposits of fissionable elements, while geothermal power taps the Earth's internal heat, which comes from a combination of residual heat from planetary accretion (about 20%) and heat produced through radioactive decay (80%).[7]

A tidal generator converts the energy of tidal flows into electricity. Greater tidal variation and higher tidal current velocities can dramatically increase the potential of a site for tidal electricity generation.

Because the Earth's tides are ultimately due to gravitational interaction with the Moon and Sun and the Earth's rotation, tidal power is practically inexhaustible and classified as a renewable energy resource. Movement of tides causes a loss of mechanical energy in the Earth–Moon system: this is a result of pumping of water through natural restrictions around coastlines and consequent viscous dissipation at the seabed and in turbulence. This loss of energy has caused the rotation of the Earth to slow in the 4.5 billion years since its formation. During the last 620 million years the period of rotation of the earth (length of a day) has increased from 21.9 hours to 24 hours;[8] in this period the Earth has lost 17% of its rotational energy. While tidal power will take additional energy from the system, the effect is negligible and would only be noticed over millions of years.

Generating methods

Tidal power can be classified into four generating methods:

Tidal stream generator

Tidal stream generators make use of the kinetic energy of moving water to power turbines, in a similar way to wind turbines that use wind to power turbines. Some tidal generators can be built into the structures of existing bridges or are entirely submersed, thus avoiding concerns over impact on the natural landscape. Land constrictions such as straits or inlets can create high velocities at specific sites, which can be captured with the use of turbines. These turbines can be horizontal, vertical, open, or ducted.[10]

Stream energy can be used at a much higher rate than wind turbines due to water being more dense than air. Using similar technology to wind turbines converting energy in tidal energy is much more efficient. Close to 10 mph (about 8.6 knots in nautical terms) ocean tidal current would have an energy output equal or greater than a 90 mph wind speed for the same size of turbine system.[11]

Tidal barrage

Tidal barrages make use of the potential energy in the difference in height (or hydraulic head) between high and low tides. When using tidal barrages to generate power, the potential energy from a tide is seized through strategic placement of specialized dams. When the sea level rises and the tide begins to come in, the temporary increase in tidal power is channeled into a large basin behind the dam, holding a large amount of potential energy. With the receding tide, this energy is then converted into mechanical energy as the water is released through large turbines that create electrical power through the use of generators.[12] Barrages are essentially dams across the full width of a tidal estuary.

Dynamic tidal power

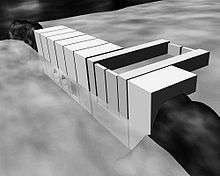

Dynamic tidal power (or DTP) is an untried but promising technology that would exploit an interaction between potential and kinetic energies in tidal flows. It proposes that very long dams (for example: 30–50 km length) be built from coasts straight out into the sea or ocean, without enclosing an area. Tidal phase differences are introduced across the dam, leading to a significant water-level differential in shallow coastal seas – featuring strong coast-parallel oscillating tidal currents such as found in the UK, China, and Korea.

Tidal lagoon

A new tidal energy design option is to construct circular retaining walls embedded with turbines that can capture the potential energy of tides. The created reservoirs are similar to those of tidal barrages, except that the location is artificial and does not contain a pre-existing ecosystem.[10] The lagoons can also be in double (or triple) format without pumping[13] or with pumping[14] that will flatten out the power output. The pumping power could be provided by excess to grid demand renewable energy from for example wind turbines or solar photovoltaic arrays. Excess renewable energy rather than being curtailed could be used and stored for a later period of time. Geographically dispersed tidal lagoons with a time delay between peak production would also flatten out peak production providing near base load production though at a higher cost than some other alternatives such as district heating renewable energy storage. The cancelled Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay in Wales, United Kingdom would have been the first tidal power station of this type once built.[15]

US and Canadian studies in the twentieth century

The first study of large scale tidal power plants was by the US Federal Power Commission in 1924 which if built would have been located in the northern border area of the US state of Maine and the south eastern border area of the Canadian province of New Brunswick, with various dams, powerhouses, and ship locks enclosing the Bay of Fundy and Passamaquoddy Bay (note: see map in reference). Nothing came of the study and it is unknown whether Canada had been approached about the study by the US Federal Power Commission.[16]

In 1956, utility Nova Scotia Light and Power of Halifax commissioned a pair of studies into the feasibility of commercial tidal power development on the Nova Scotia side of the Bay of Fundy. The two studies, by Stone & Webster of Boston and by Montreal Engineering Company of Montreal independently concluded that millions of horsepower could be harnessed from Fundy but that development costs would be commercially prohibitive at that time.[17]

There was also a report on the international commission in April 1961 entitled "Investigation of the International Passamaquoddy Tidal Power Project" produced by both the US and Canadian Federal Governments. According to benefit to costs ratios, the project was beneficial to the US but not to Canada. A highway system along the top of the dams was envisioned as well.

A study was commissioned by the Canadian, Nova Scotian and New Brunswick governments (Reassessment of Fundy Tidal Power) to determine the potential for tidal barrages at Chignecto Bay and Minas Basin – at the end of the Fundy Bay estuary. There were three sites determined to be financially feasible: Shepody Bay (1550 MW), Cumberline Basin (1085 MW), and Cobequid Bay (3800 MW). These were never built despite their apparent feasibility in 1977.[18]

US studies in the twenty first century

The Snohomish PUD, a public utility district located primarily in Snohomish county, Washington State, began a tidal energy project in 2007[19]; in April of 2009 the PUD selected OpenHydro[20], a company based in Ireland, to develop turbines and equipment for eventual installation. The project as initially designed was to place generation equipment in areas of high tidal flow and operate that equipment for four to five years. After the trial period the equipment would be removed. The project was initially budgeted at a total cost of $10 million dollars, with half of that funding provided by the PUD out of utility reserve funds, and half from grants, primarily from the US federal government. The PUD paid for a portion of this project with reserves and received a $900,000 grant in 2009 and a $3.5 million dollar grant in 2010 in addition to using reserves to pay an estimated $4 million dollars of costs. In 2010 the budget estimate was increased to $20 million dollars, half to be paid by the utility, half by the federal government. The Utility was unable to control costs on this project, and by Oct of 2014 the costs had ballooned to an estimated $38 million dollars and were projected to continue to increase. The PUD proposed that the federal government provide an additional $10 million dollars towards this increased cost citing a "gentlemans agreement"[21]. When the federal government refused to provide the additional funding the project was cancelled by the PUD after spending nearly $10 million dollars in reserves and grants. The PUD abandoned all tidal energy exploration after this project was cancelled and does not own or operate any tidal energy sources.

Tidal power development in the UK

The world's first marine energy test facility was established in 2003 to start the development of the wave and tidal energy industry in the UK. Based in Orkney, Scotland, the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) has supported the deployment of more wave and tidal energy devices than at any other single site in the world. EMEC provides a variety of test sites in real sea conditions. Its grid connected tidal test site is located at the Fall of Warness, off the island of Eday, in a narrow channel which concentrates the tide as it flows between the Atlantic Ocean and North Sea. This area has a very strong tidal current, which can travel up to 4 m/s (8 knots) in spring tides. Tidal energy developers that have tested at the site include: Alstom (formerly Tidal Generation Ltd); ANDRITZ HYDRO Hammerfest; Atlantis Resources Corporation; Nautricity; OpenHydro; Scotrenewables Tidal Power; Voith.[22] The resource could be 4 TJ per year.[23] Elsewhere in the UK, annual energy of 50 TWh can be extracted if 25 GW capacity is installed with pivotable blades.[24][25][26]

Current and future tidal power schemes

- The Rance tidal power plant built over a period of 6 years from 1960 to 1966 at La Rance, France.[27] It has 240 MW installed capacity.

- 254 MW Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Plant in South Korea is the largest tidal power installation in the world. Construction was completed in 2011.[28][29]

- The first tidal power site in North America is the Annapolis Royal Generating Station, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, which opened in 1984 on an inlet of the Bay of Fundy.[30] It has 20 MW installed capacity.

- The Jiangxia Tidal Power Station, south of Hangzhou in China has been operational since 1985, with current installed capacity of 3.2 MW. More tidal power is planned near the mouth of the Yalu River.[31]

- The first in-stream tidal current generator in North America (Race Rocks Tidal Power Demonstration Project) was installed at Race Rocks on southern Vancouver Island in September 2006.[32][33] The Race Rocks project was shut down after operating for five years (2006-2011) because high operating costs produced electricity at a rate that was not economically feasible.[34] The next phase in the development of this tidal current generator will be in Nova Scotia (Bay of Fundy).[35]

- A small project was built by the Soviet Union at Kislaya Guba on the Barents Sea. It has 0.4 MW installed capacity. In 2006 it was upgraded with a 1.2MW experimental advanced orthogonal turbine.

- Jindo Uldolmok Tidal Power Plant in South Korea is a tidal stream generation scheme planned to be expanded progressively to 90 MW of capacity by 2013. The first 1 MW was installed in May 2009.[36]

- A 1.2 MW SeaGen system became operational in late 2008 on Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland.[37]

- The contract for an 812 MW tidal barrage near Ganghwa Island (South Korea) north-west of Incheon has been signed by Daewoo. Completion is planned for 2015.[28]

- A 1,320 MW barrage built around islands west of Incheon is proposed by the South Korean government, with projected construction starting in 2017.[38]

- The Scottish Government has approved plans for a 10MW array of tidal stream generators near Islay, Scotland, costing 40 million pounds, and consisting of 10 turbines – enough to power over 5,000 homes. The first turbine is expected to be in operation by 2013.[39]

- The Indian state of Gujarat is planning to host South Asia's first commercial-scale tidal power station. The company Atlantis Resources planned to install a 50MW tidal farm in the Gulf of Kutch on India's west coast, with construction starting early in 2012.[40]

- Ocean Renewable Power Corporation was the first company to deliver tidal power to the US grid in September, 2012 when its pilot TidGen system was successfully deployed in Cobscook Bay, near Eastport.[41]

- In New York City, 30 tidal turbines will be installed by Verdant Power in the East River by 2015 with a capacity of 1.05MW.[42]

- Construction of a 320 MW tidal lagoon power plant outside the city of Swansea in the UK was granted planning permission in June 2015 and work is expected to start in 2016. Once completed, it will generate over 500GWh of electricity per year, enough to power roughly 155,000 homes.[43]

- A turbine project is being installed in Ramsey Sound in 2014.[44][45]

- The largest tidal energy project entitled MeyGen (398MW) is currently in construction in the Pentland Firth in northern Scotland [46]

- A combination of 5 tidal stream turbines from Tocardo are placed in the Oosterscheldekering, the Netherlands, and have been operational since 2015 with a capacity of 1,2 MW [47]

Tidal power issues

Environmental concerns

Tidal power can have effects on marine life. The turbines can accidentally kill swimming sea life with the rotating blades, although projects such as the one in Strangford feature a safety mechanism that turns off the turbine when marine animals approach.[48] Some fish may no longer utilize the area if threatened with a constant rotating or noise-making object. Marine life is a huge factor when placing tidal power energy generators in the water and precautions are made to ensure that as many marine animals as possible will not be affected by it. The Tethys database provides access to scientific literature and general information on the potential environmental effects of tidal energy.[49]

Tidal turbines

The main environmental concern with tidal energy is associated with blade strike and entanglement of marine organisms as high speed water increases the risk of organisms being pushed near or through these devices. As with all offshore renewable energies, there is also a concern about how the creation of EMF and acoustic outputs may affect marine organisms. Because these devices are in the water, the acoustic output can be greater than those created with offshore wind energy. Depending on the frequency and amplitude of sound generated by the tidal energy devices, this acoustic output can have varying effects on marine mammals (particularly those who echolocate to communicate and navigate in the marine environment, such as dolphins and whales). Tidal energy removal can also cause environmental concerns such as degrading farfield water quality and disrupting sediment processes.[50] Depending on the size of the project, these effects can range from small traces of sediment building up near the tidal device to severely affecting nearshore ecosystems and processes.[51]

Tidal barrage

Installing a barrage may change the shoreline within the bay or estuary, affecting a large ecosystem that depends on tidal flats. Inhibiting the flow of water in and out of the bay, there may also be less flushing of the bay or estuary, causing additional turbidity (suspended solids) and less saltwater, which may result in the death of fish that act as a vital food source to birds and mammals. Migrating fish may also be unable to access breeding streams, and may attempt to pass through the turbines. The same acoustic concerns apply to tidal barrages. Decreasing shipping accessibility can become a socio-economic issue, though locks can be added to allow slow passage. However, the barrage may improve the local economy by increasing land access as a bridge. Calmer waters may also allow better recreation in the bay or estuary.[51] In August 2004, a humpback whale swam through the open sluice gate of the Annapolis Royal Generating Station at slack tide, ending up trapped for several days before eventually finding its way out to the Annapolis Basin.[52]

Tidal lagoon

Environmentally, the main concerns are blade strike on fish attempting to enter the lagoon, acoustic output from turbines, and changes in sedimentation processes. However, all these effects are localized and do not affect the entire estuary or bay.[51]

Corrosion

Salt water causes corrosion in metal parts. It can be difficult to maintain tidal stream generators due to their size and depth in the water. The use of corrosion-resistant materials such as stainless steels, high-nickel alloys, copper-nickel alloys, nickel-copper alloys and titanium can greatly reduce, or eliminate, corrosion damage.

Mechanical fluids, such as lubricants, can leak out, which may be harmful to the marine life nearby. Proper maintenance can minimize the amount of harmful chemicals that may enter the environment.

Fouling

The biological events that happen when placing any structure in an area of high tidal currents and high biological productivity in the ocean will ensure that the structure becomes an ideal substrate for the growth of marine organisms. In the references of the Tidal Current Project at Race Rocks in British Columbia this is documented. Also see this page and Several structural materials and coatings were tested by the Lester Pearson College divers to assist Clean Current in reducing fouling on the turbine and other underwater infrastructure.

Cost

Tidal Energy has an expensive initial cost which may be one of the reasons tidal energy not a popular source of renewable energy. It is important to realize that the methods for generating electricity from tidal energy is a relatively new technology. It is projected that tidal power will be commercially profitable within 2020 with better technology and larger scales. Tidal Energy is however still very early in the research process and the ability to reduce the price of tidal energy can be an option. The cost effectiveness depends on each site tidal generators are being placed. To figure out the cost effectiveness they use the Gilbert ratio, which is the length of the barrage in metres to the annual energy production in kilowatt hours (1 kilowatt hour = 1 KWH = 1000 watts used for 1 hour).[53]

Due to tidal energy reliability the expensive upfront cost of these generators will slowly be paid off. Due to the success of a greatly simplified design, the orthogonal turbine offers considerable cost savings. As a result the production period of each generating unit is reduced, lower metal consumption is needed and technical efficiency is greater. [54]Scientific research has the capability to have a renewable resource like tidal energy that is affordable as well as profitable.

Structural health monitoring

The high load factors resulting from the fact that water is 800 times denser than air and the predictable and reliable nature of tides compared with the wind makes tidal energy particularly attractive for electric power generation. Condition monitoring is the key for exploiting it cost-efficiently.[55]

See also

References

- ↑ Ocean Energy Council (2011). "Tidal Energy: Pros for Wave and Tidal Power". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - RS01j.doc" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ Minchinton, W. E. (October 1979). "Early Tide Mills: Some Problems". Technology and Culture. 20 (4): 777–786. doi:10.2307/3103639. JSTOR 3103639.

- ↑ Dorf, Richard (1981). The Energy Factbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness world records 2014. ISBN 9781908843159.

- ↑ DiCerto, JJ (1976). The Electric Wishing Well: The Solution to the Energy Crisis. New York: Macmillan.

- ↑ Turcotte, D. L.; Schubert, G. (2002). "Chapter 4". Geodynamics (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-521-66624-4.

- ↑ George E. Williams (2000). "Geological constraints on the Precambrian history of Earth's rotation and the Moon's orbit". Reviews of Geophysics. 38 (1): 37–60. Bibcode:2000RvGeo..38...37W. doi:10.1029/1999RG900016.

- ↑ Douglas, C. A.; Harrison, G. P.; Chick, J. P. (2008). "Life cycle assessment of the Seagen marine current turbine". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part M: Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment. 222 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1243/14750902JEME94.

- 1 2 "Tidal - Capturing tidal fluctuations with turbines, tidal barrages, or tidal lagoons". Tidal / Tethys. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "Tidal Stream and Tidal Stream Energy Devices of the Sea". Alternative Energy Tutorials. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ↑ Evans, Robert (2007). Fueling Our Future: An Introduction to Sustainable Energy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "Hydrological Changing Double Current-typed Tidal Power Generation" (video). Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ "Enhancing Electrical Supply by Pumped Storage in Tidal Lagoons" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ Elsevier Ltd, The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom. "Green light for world's first tidal lagoon". renewableenergyfocus.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ↑ "Niagara's Power From The Tides" Archived 2015-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. May 1924 Popular Science Monthly

- ↑ Nova Scotia Light and Power Company, Limited, Annual Report, 1956

- ↑ Chang, Jen (2008), "6.1", Hydrodynamic Modeling and Feasibility Study of Harnessing Tidal Power at the Bay of Fundy (PDF) (PhD thesis), Los Angeles: University of Southern California, Bibcode:2008PhDT.......107C, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-22, retrieved 2011-09-27

- ↑ Overview,”

- ↑ Selected,”

- ↑ “PUD claims 'gentlemans agreement over tidal project funding',” Everett Herald, Oct 2, 2014

- ↑ "EMEC: European Marine Energy Centre". emec.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2007-01-27.

- ↑ Lewis, M.; Neill, S.P.; Robins, P.E.; Hashemi, M.R. (2015). "Resource assessment for future generations of tidal-stream energy arrays". Energy. 83: 403–415. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.02.038.

- ↑ "Norske oppfinneres turbinteknologi kan bli brukt i britisk tidevannseventyr". Teknisk Ukeblad. 14 January 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ L'Usine marémotrice de la Rance Archived April 8, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Hunt for African Projects". Newsworld.co.kr. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "Tidal power plant nears completion". yonhapnews.co.kr. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25.

- ↑ "Nova Scotia Power - Environment - Green Power- Tidal". Nspower.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "China Endorses 300 MW Ocean Energy Project". Renewableenergyworld.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "Race Rocks Demonstration Project". Cleancurrent.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "Tidal Energy, Ocean Energy". Racerocks.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ "Tidal Energy Turbine Removal". Race Rocks Ecological Reserve- Marine mammals, seabirds. 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ↑ "Information for media inquiries". Cleancurrent.com. 2009-11-13. Archived from the original on 2007-06-03. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ↑ Korea's first tidal power plant built in Uldolmok, Jindo

- ↑ "Tidal energy system on full power". BBC News. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ↑ $ 3-B tidal power plant proposed near Korean islands

- ↑ "Islay to get major tidal power scheme". BBC. March 17, 2011. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ↑ "India plans Asian tidal power first". BBC News. January 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011.

- ↑ "1st tidal power delivered to US grid off Maine" Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., CBS MoneyWatch, September 14, 2012

- ↑ "Turbines Off NYC East River Will Create Enough Energy to Power 9,500 Homes". U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ↑ Oliver, Antony (9 June 2015). "Swansea Tidal Lagoon power plant wins planning permission". Infrastructure Intelligence. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ↑ Macalister, Terry. "Tidal power firm signs deal to sell electricity to EDF Energy Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine." The Guardian, 25 September 2014.

- ↑ , Ellie. "First full-scale tidal generator in Wales unveiled: Deltastream array to power 10,000 homes using ebb and flow of the ocean Archived 2014-10-23 at Archive.is" Daily Mail, 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-08-18. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ↑ "Tidal Energy Technology Brief" (PDF). International Renewable Energy Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Tethys". Archived from the original on 2014-11-10.

- ↑ Martin-Short, R.; Hill, J.; Kramer, S. C.; Avdis, A.; Allison, P. A.; Piggott, M. D. (2015-04-01). "Tidal resource extraction in the Pentland Firth, UK: Potential impacts on flow regime and sediment transport in the Inner Sound of Stroma". Renewable Energy. 76: 596–607. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2014.11.079.

- 1 2 3 "Tethys". Archived from the original on 2014-05-25.

- ↑ "Whale still drawing crowds at N.S. river". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Tidal Energy - Ocean Energy Council". Ocean Energy Council. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ↑ Sveinsson, Níels. "Profitability Assessment for a Tidal Power Plant at the Mouth of Hvammsfjörður, Iceland" (PDF).

- ↑ "Structural Health Monitoring in Composite Tidal energy converters". Archived from the original on 2014-03-25.

Further reading

- Baker, A. C. 1991, Tidal power, Peter Peregrinus Ltd., London.

- Baker, G. C., Wilson E. M., Miller, H., Gibson, R. A. & Ball, M., 1980. "The Annapolis tidal power pilot project", in Waterpower '79 Proceedings, ed. Anon, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, pp 550–559.

- Hammons, T. J. 1993, "Tidal power", Proceedings of the IEEE, [Online], v81, n3, pp 419–433. Available from: IEEE/IEEE Xplore. [July 26, 2004].

- Lecomber, R. 1979, "The evaluation of tidal power projects", in Tidal Power and Estuary Management, eds. Severn, R. T., Dineley, D. L. & Hawker, L. E., Henry Ling Ltd., Dorchester, pp 31–39.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tidal power. |

- Enhanced tidal lagoon with pumped storage and constant output as proposed by David J.C. MacKay, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, UK.

- Marine and Hydrokinetic Technology Database The U.S. Department of Energy's Marine and Hydrokinetic Technology Database provides up-to-date information on marine and hydrokinetic renewable energy, both in the U.S. and around the world.

- Tethys Database A database of information on potential environmental effects of marine and hydrokinetic and offshore wind energy development.

- Severn Estuary Partnership: Tidal Power Resource Page

- Location of Potential Tidal Stream Power sites in the UK

- University of Strathclyde ESRU—Detailed analysis of marine energy resource, current energy capture technology appraisal and environmental impact outline

- Coastal Research - Foreland Point Tidal Turbine and warnings on proposed Severn Barrage

- Sustainable Development Commission - Report looking at 'Tidal Power in the UK', including proposals for a Severn barrage

- World Energy Council - Report on Tidal Energy

- European Marine Energy Centre - Listing of Tidal Energy Developers -retrieved 1 July 2011 (link updated 31 January 2014)

- Resources on Tidal Energy

- Structural Health Monitoring of composite tidal energy converters