Congestive hepatopathy

| Congestive hepatopathy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph of congestive hepatopathy demonstrating perisinusoidal fibrosis and centrilobular (zone III) sinusoidal dilation. Liver biopsy. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | gastroenterology |

| ICD-10 | K76.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 573.8 |

Congestive hepatopathy, also known as nutmeg liver and chronic passive congestion of the liver, is liver dysfunction due to venous congestion, usually due to congestive heart failure. The gross pathological appearance of a liver affected by chronic passive congestion is "speckled" like a grated nutmeg kernel; the dark spots represent the dilated and congested hepatic venules and small hepatic veins. The paler areas are unaffected surrounding liver tissue. When severe and longstanding, hepatic congestion can lead to fibrosis; if congestion is due to right heart failure, it is called cardiac cirrhosis.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms depend largely upon the primary lesions giving rise to the condition. In addition to the heart or lung symptoms, there will be a sense of fullness and tenderness in the right hypochondriac region. Gastrointestinal catarrh is usually present, and vomiting of blood may occur. There is usually more or less jaundice. Owing to portal obstruction, ascites occurs, followed later by generalised oedema. The stools are light or clay-colored, and the urine is colored by bile. On palpation, the liver is found enlarged and tender, sometimes extending several inches below the costal margin of the ribs.

Pathophysiology

Increased pressure in the sublobular branches of the hepatic veins causes an engorgement of venous blood, and is most frequently due to chronic cardiac lesions, especially those affecting the right heart (e.g., right-sided heart failure), the blood being dammed back in the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins. Central regions of the hepatic lobules are red–brown and stand out against the non-congested, tan-coloured liver. Centrilobular necrosis occurs.

Macroscopically, the liver has a pale and spotty appearance in affected areas, as stasis of the blood causes pericentral hepatocytes (liver cells surrounding the central venule of the liver) to become deoxygenated compared to the relatively better-oxygenated periportal hepatocytes adjacent to the hepatic arterioles. This retardation of the blood also occurs in lung lesions, such as chronic interstitial pneumonia, pleural effusions, and intrathoracic tumors.

Diagnosis

Hepatic congestion should be suspected in patients with the above clinical and laboratory features in the setting of congestive heart failure or other cardiac condition associated with elevated central venous pressure. Other causes of liver dysfunction should also be considered, including biliary obstruction, acute or chronic viral hepatitis, hepatic infiltrative disorders, and drug or herbal medication toxicity, depending upon the clinical setting.

In addition to a careful history (ie, risk factors for liver disease and medications that might contribute to hepatic injury) and a physical examination, a reasonable evaluation might include the following:

●Laboratory testing – Serologic testing for viral hepatitis, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease (especially in a young person), autoimmune hepatitis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, celiac disease, and thyroid dysfunction can be obtained.

In one study, a markedly elevated serum N-terminal-proBNP level distinguished ascites due to heart failure from ascites due to cirrhosis [20]. In another study, a serum BNP level >364 pg/mL had a sensitivity of 98 percent for heart failure-related ascites, and a level <182 pg/mL excluded heart failure-related ascites [21]. (See "Evaluation of adults with ascites".)

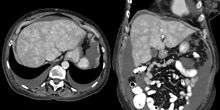

●Imaging – Imaging studies include right upper quadrant ultrasonography with Doppler studies of the portal and hepatic veins and hepatic artery, electrocardiogram, and echocardiography. Characteristic findings on conventional imaging studies include dilatation of the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins, retrograde hepatic venous opacification shortly after intravenous contrast injection, and heterogeneous hepatic enhancement due to stagnant blood flow [22]. Other imaging approaches to identify hepatic congestion and assess fibrosis, including diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance elastography, are under study [22-24].

●Diagnostic paracentesis – Patients with ascites should undergo a diagnostic paracentesis, which typically reveals a high ascitic protein content, usually greater than 2.5 g/dL, reflecting the relatively well-preserved serum albumin levels and the contribution of "hepatic lymph" to the ascites. The increased protein is presumed to be due to the rupture of hepatic lymphatics, which are rich in protein. The serum-to-ascites albumin gradient is ≥1.1, reflecting portal hypertension [25].

Improvement in liver biochemical tests with treatment of the underlying cardiac condition provides support for the diagnosis. A liver biopsy can help confirm the diagnosis in equivocal cases (particularly in patients with coexisting liver disease) and establish the severity of histologic injury, but it is rarely required. Before considering a percutaneous liver biopsy, careful attention should be given to coagulation parameters, and a percutaneous biopsy should not be performed in patients with ascites.

Treatment

Treatment is directed largely to removing the cause, or, where that is impossible, to modifying its effects. Thus, therapy aimed at improving right heart function will also improve congestive hepatopathy. True nutmeg liver is usually secondary to left-sided heart failure causing congestive right heart failure, so treatment options are limited.

See also

References

- ↑ Giallourakis CC, Rosenberg PM, Friedman LS (2002). "The liver in heart failure". Clin Liver Dis. 6 (4): 947–67, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/S1089-3261(02)00056-9. PMID 12516201.