Atrophic gastritis

| Atrophic gastritis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Atrophic gastritis | |

| Specialty |

Gastroenterology |

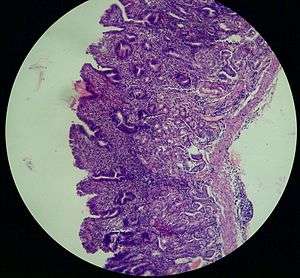

Atrophic gastritis (also known as Type A or Type B Gastritis more specifically)[1] is a process of chronic inflammation of the stomach mucous membrane (mucosa), leading to loss of gastric glandular cells and their eventual replacement by intestinal and fibrous tissues. As a result, the stomach's secretion of essential substances such as hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and intrinsic factor is impaired, leading to digestive problems. The most common are vitamin B12 deficiency which results in a megaloblastic anemia and malabsorption of iron, leading to iron deficiency anaemia.[2] It can be caused by persistent infection with Helicobacter pylori, or can be autoimmune in origin. Those with the autoimmune version of atrophic gastritis are statistically more likely to develop gastric carcinoma, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and achlorhydria.

Type A gastritis primarily affects the body/fundus of the stomach, and is more common with pernicious anemia.[1]

Type B gastritis primarily affects the antrum, and is more common with H. pylori infection.[1]

Presentation

Associated conditions

Patients with atrophic gastritis are also at increased risk for the development of gastric adenocarcinoma.[3] The optimal endoscopic surveillance strategy is not known but all nodules and polyps should be removed in these patients.

Causes

Recent research has shown that AMAG is a result of the immune system attacking the parietal cells.[4]

Environmental Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis (EMAG) is due to environmental factors, such as diet and H. pylori infection. EMAG is typically confined to the body of the stomach. Patients with EMAG are also at increased risk of gastric carcinoma.

Pathophysiology

.jpg)

Autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) is an inherited form of atrophic gastritis characterized by an immune response directed toward parietal cells and intrinsic factor.[4] The presence of serum antibodies to parietal cells and to intrinsic factor are characteristic findings. The autoimmune response subsequently leads to the destruction of parietal cells, which leads to profound hypochlorhydria (and elevated gastrin levels). The inadequate production of intrinsic factor also leads to vitamin B12 malabsorption and pernicious anemia. AMAG is typically confined to the gastric body and fundus.

Hypochlorhydria induces G cell (gastrin-producing) hyperplasia, which leads to hypergastrinemia. Gastrin exerts a trophic effect on enterochromaffin-like cells (ECL cells are responsible for histamine secretion) and is hypothesized to be one mechanism to explain the malignant transformation of ECL cells into carcinoid tumors in AMAG.

Diagnosis

Detection of APCA, AIFA and HP antibodies in conjunction with serum gastrin are effective for diagnostic purposes.[5]

Classification

The notion that Atrophic gastritis could be classified depending on the level of progress as "close type" or "open type" was suggested in early studies,[6] but no universally accepted classification exists as of 2017.[5]

Treatment

Immunosupressive drugs and chemotherapy with antineoplastic drugs are potential treatment options for AMAG. In the case of confirmed malignancy of stomach, stomach resection may be required.

References

- 1 2 3 Blaser MJ (May 1988). "Type B gastritis, aging, and Campylobacter pylori". Arch. Intern. Med. 148 (5): 1021–2. doi:10.1001/archinte.1988.00380050027005. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 3365072.

- ↑ Annibale B, Capurso G, Lahner E, Passi S, Ricci R, Maggio F, Delle Fave G (April 2003). "Concomitant alterations in intragastric pH and ascorbic acid concentration in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis and associated iron deficiency anaemia". Gut. 52 (4): 496–501. doi:10.1136/gut.52.4.496. ISSN 0017-5749. PMC 1773597. PMID 12631657.

- ↑ Giannakis M, Chen SL, Karam SM, Engstrand L, Gordon JI (March 2008). "Helicobacter pylori evolution during progression from chronic atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer and its impact on gastric stem cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (11): 4358–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800668105. PMC 2393758. PMID 18332421.

- 1 2 Nimish Vakil, MD, Clinical Adjunct Professor, University of Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. "Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis: Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Merck Manual Professional". MSD Manual Professional Version. Merck & Co.

- 1 2 Minalyan A, Benhammou JN, Artashesyan A, Lewis MS, Pisegna JR (2017). "Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives". Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 10: 19–27. doi:10.2147/CEG.S109123. PMC 5304992. PMID 28223833.

- ↑ Kimura, K.; Takemoto, T. (2008). "An Endoscopic Recognition of the Atrophic Border and its Significance in Chronic Gastritis". Endoscopy. 1 (03): 87–97. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1098086. ISSN 0013-726X.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |