National Agrarian Party

National Agrarian Party Partidul Național-Agrar | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| President | Octavian Goga |

| Founded | April 10, 1932 |

| Dissolved | July 14, 1935 |

| Split from | People's Party |

| Succeeded by | National Christian Party |

| Newspaper | Țara Noastră |

| Ideology |

Agrarianism National conservatism (Romanian) Antisemitism Monarchism Germanophilia Corporatism Dirigisme Fascism (disputed) |

| Political position | Right-wing to far-right |

| National affiliation | Antirevisionist League (1933) |

| Slogan |

Dumnezeu, Patrie, Rege ("God, Fatherland, King") Rod mult, bun și cu preț ("More, better, valuable bearings") |

The National Agrarian Party (Romanian: Partidul Național-Agrar or Partidul Național-Agrarian, PNA) was a right-wing agrarian party active in Romania during the early 1930s. Established and led by poet Octavian Goga, it was originally a schism from the more moderate People's Party, espousing national conservatism, monarchism, agrarianism, antisemitism, and Germanophilia; Goga was also positively impressed by fascism, but there is disagreement in the scholarly community as to whether the PNA was itself fascist. Its antisemitic rhetoric was also contrasted by the PNA's acceptance of some Jewish members, including Tudor Vianu and Henric Streitman. The group was generally suspicious of Romania's other ethnic minorities, but in practice accepted members and external collaborators of many ethnic backgrounds, including the Romani Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică.

The National Agrarianist economic and social program rested on the protection of smallholders, with echoes of dirigisme and promises of debt relief. It was strongly opposed to the more left-wing National Peasants' Party, describing it as corrupt and denouncing its autonomist-regionalist tendencies. In Parliament, PNA representatives, largely inherited from the People's Party, collaborated mostly with two other anti-establishment groups: the Georgist Liberals and the Lupist Peasantists. The PNA was able to absorb some National Peasantist sections, primarily in Bucharest and Transylvania.

The PNA registered its best result nationally in the December 1933 election, when it took 4.1% of the vote. Despite its relative insignificance, its leader Goga was often perceived as a likely contender for the office of Prime Minister. The PNA had contacts in Nazi Germany, who regarded it as a political ally. While cautious about the Nazis' take on international politics, Goga traveled to Berlin in late 1933, meeting Adolf Hitler and returning as an enthusiastic admirer. Moving closer to the far-right and abandoning his own membership in the Romanian Freemasonry, Goga sought alliances with the more radical movements. The PNA tried but failed to unite with the Iron Guard and the Romanian Front, finally merging with the slightly more powerful National-Christian Defense League in July 1935.

The resulting National Christian Party offered a venue for conservative antisemites with fascist sympathies, but was rejected by PNA moderates, as well as by some of the League's radicals. A splinter group, led by Ion Al. Vasilescu-Valjean and centered on Romanați County, continued to call itself PNA, surviving to at least 1937.

History

Emergence

The party emerged with a split in the more mainstream People's Party (PP), which was led by General Alexandru Averescu. This followed a major dispute between Averescu and Goga, prompted by the latter's unconditional support for Romania's authoritarian King, Carol II. Historian Adolf Minuț argues that Carol personally intervened to create a rift between the two men, this being one of a "web of Carlist machinations" to isolate his constitutionalist adversaries.[1] The same is noted by memoirist Vasile Netea, who describes Carol as performing "scissiparity" on the old parties.[2] In January 1932, Goga had vaguely announced his bid for the PP chairmanship, while also hinting that he was prepared to leave with his partisans if his candidacy were to be rejected.[3] On March 3, Averescu formally denounced Goga's maneuvers in a circular letter to regional affiliates, noting that a conspiracy was in place to break up the PP.[4] In response, Goga accused Averescu of tarnishing the crown's prestige.[5]

The split also consecrated the independence of Goga's faction of the PP, which was also situated on the extreme of Romanian nationalism, with "some sympathies toward fascism".[6] However, the new group was also able to absorb more moderate sections of the PP, leaving Averescu's group severely weakened.[7] Averescu and his colleague, Grigore Trancu-Iași, fought back by asking for all dissidents still holding seats in the Assembly of Deputies to be deposed. This proposal was eventually defeated by a vote, during which the National Liberal Party voted in Goga's favor.[8]

Goga's party originated with a PP congress at Enescu restaurant on March 12, attended by 45 of 65 sections, which proclaimed Goga as People's Party chairman. By March 21, Averescu was able to regain control over most PP chapters, though he lost all presence in places such as Argeș, Cluj, and Mehedinți.[9] Following this confrontation, Goga announced he would take on the "painful task" of leaving Averescu's group.[10] As noted by scholar Armin Heinen, the National Agrarians' genesis coincided with the parallel rise of the Nazi Party in Weimar Germany: the PNA began organizing during Weimar's presidential election, in which Adolf Hitler came second.[11]

Goga's "general staff" included former minister Ion Petrovici, alongside Ion Al. Vasilescu-Valjean and C. Brăescu, who had been Vice Presidents of the Deputies' Assembly.[12] Three other prominent Averescu supporters, Leon Scridon,[13] Silviu Dragomir and Ioan Lupaș,[14] also joined Goga during his departure. Early defectors also included a large part of the PP eminences in Transylvania and the Banat: Eugen P. Barbul, Sebastian Bornemisa, Laurian Gabor, and Petru Nemoianu.[15] This remained "the most painful" of all schisms endured by the PP.[16] On April 10, 1932, this dissidence held its congress at Rio Cinema, Bucharest. Its first presidium included Lupaș, General Constantin Iancovescu, Stan Ghițescu, Ilie Rădulescu, and Iancu Isvoranu; Goga was reconfirmed as People's Party chairman, before the party changed names.[17] The "PNA" name was adopted hours later, following a motion submitted by deputy D. D. Burileanu—having been first submitted for discussion a week earlier, during a more private meeting of party leaders.[18] The group registered as its electoral symbol "two dots within a circumference",[19] sometimes described as a circle with "two eyes".[20] Whether intentionally or not, this symbol closely resembled the circle used by a more democratic agrarian group, the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ).[21] Transylvanian defectors from the PNȚ initially organized some of the PNA branches, but, in June 1932, returned to their old party.[22] More dedicated support came from the former PNȚ chapters in Ilfov County and the "Black" (northeastern) sector of Bucharest, which were absorbed into Goga's new movement.[23]

PNA cadres included four important figures in Romania's commercial and industrial life, who, as Netea writes, were especially treasured by Goga. These were Ghițescu, Tilică Ioanid, I. D. Enescu, and Leon Gigurtu.[24] The group also reached out of its PP constituency, and had traction among people not previously involved in party politics, such as Virgil Molin, a journalist and president of the Craiova chamber of labor.[25] Also joining the PNA were the literary critic Tudor Vianu[26] and his brother, the essayist Alexandru Vianu, alongside poet Sandu Tudor and philosopher Alexandru Mironescu.[27] Țara Noastră, put out from Transylvania by Ion Gorun, endured as the central party organ, with another party newspaper of the same name appearing at Buzău.[28] While establishing itself regionally, Goga's party took over or established several regional newspapers: Cuvântul Poporului, put out by Elie Mărgeanu of Sibiu; Agrarul Vâlcei, published by Dumitru Zeana in Râmnicu Vâlcea; Cârma Vremii of Iași and Chemarea of Vaslui; as well as two sheets in Brăila and Constanța, both named Brazda Nouă.[29]

Platform

Conservatism, radicalism, agrarianism

As Heinen notes, the PNA was one of several groups channeling popular discontent following the Great Depression; it was also the most authentic, and a "remarkable force."[30] Historian Stanley G. Payne describes the splinter group as authoritarian nationalist and "rightist", or "rather more overtly right radical" than Mihail Manoilescu's own dissident faction.[31] The issue of its labeling has caused some disputes in the community of experts. Nicholas Nagy-Talavera viewed Goga as a "bourgeois fascist", but his assessment was challenged by Heinen, according to whom the PNA's "radical nationalism" was "entirely devoid of that revolutionary pathos which set apart all the fascist parties."[32] Overall, "too many PNA members were still tied to the People's Party directives in both manners and ideas of political combat."[33] However, according to scholar Irina Livezeanu, Goga was in the process of migrating "across the conservative-radical divide".[34]

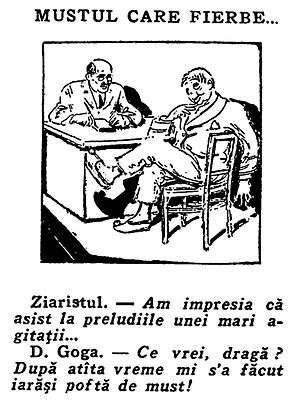

While reaching out to the far-right, the PNA was also staunchly monarchist—according to Heinen, Goga was a "national conservative" among the "Carlists".[35] The National Agrarians adopted Dumnezeu, Patrie, Rege ("God, Fatherland, King") as their slogan, a rallying cry already associated with Goga before the party's formation.[36] The group's rejection of democracy had its roots in Goga's 1927 book, Mustul care fierbe ("The Frothing Must"), which argued that the masses needed a "moral eminence" to "inspire in them tranquility and safety."[37] The PNA suggested modifying Romania's Constitution of 1923, reducing Parliament to an "orderly and useful instrument", reformed around a corporative representation.[38]

In time, the PNA adopted another slogan: Rod mult, bun și cu preț ("More, better, valuable bearings"). This notion reflected its commitment to an agrarian economy, which Goga identified as the core of Romania's potential for export, in tandem with the Romanianization of labor and capital.[39] Goga's agrarianism rested on the notion that peasants were a unifying factor, their shared culture transcending regional divisions.[40] In 1935, Valjean similarly proclaimed that all classes were "subordinate to the plowmen".[41] His PNA intended to make the smallholders key players in Romania's economy, encouraging credit unions and land purchase, as well as describing a future in which labor and its product would be more expensive; it also promised to enact agricultural dirigisme, with tools such as a state plan for developing agriculture, pomology, sericulture, and handicrafts.[42]

While seeking ways to improve the peasants' economic status, the party pledged itself to administrative reform and a full clampdown on corruption.[16][43] By October 1932, its deputies were engaged in a public confrontation with the PNȚ cabinet, headed by Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, over the issue of debt relief. Goga wanted most of the small- and mid-sized plots to be cleared of debt with state support, and wanted to extend that principle to public debt held by urban localities.[44] Such proposals were balanced out by the PNA's adversity toward decentralizing projects, in which Goga saw evidence of pushes for Transylvanian autonomism, as endorsed by the PNȚ.[45] Historian Oltea Rășcanu Gramaticu, who focused on the politics of Tutova County, noted that the PNA enjoyed "some popularity", due to its "radical solutions for revitalizing small plots owned by the peasants".[46] However, as argued by researchers Cornel Popescu and George Daniel Ungureanu, the PNA was agrarian "in name", and had a mostly right-wing program.[47]

The PNA on minorities

The party's stances evidenced Goga's conversion to antisemitism, which he had not explicitly embraced before 1932; within that framework, Goga was arguing that Jews were endorsing "Magyarization" in Transylvania.[48] However, already in the 1910s Goga was modelling himself on Karl Lueger, Cisleithania's antisemitic doctrinaire.[49] In the 1920s, his Țara Noastră had expressed sympathy with the growing antisemitic trend among students, and indirectly with the Iron Guard.[50] In Mustul care fierbe, Goga further hinted that Jews were to blame for the ills of modernity.[51] He voiced alarm about Greater Romania being invaded by "parasites" and "guess... who". However, he framed his support for the students in terms of social rejuvenation, and noted that violent antisemitism was perhaps an "incorrect slogan".[52] During the elections of 1926, Goga, as Minister of the Interior, had obtained favors for A. C. Cuza's National-Christian Defense League (LANC), which was virulently antisemitic. However, his assistance proved a moderating influence, obliging Cuza to purge the LANC of radicals such as Ion Zelea Codreanu, Valer Pop, and Traian Brăileanu.[53]

In 1931, Goga was still reassuring his readers that he was not an antisemite.[54] According to Minuț, his subsequent drift was a consequence of his taking money from antisemitic industrialists, and in particular from Ion Gigurtu.[55] Xenophobic radicalization was additionally enhanced by the PNA–PNȚ conflict: Goga castigated his adversaries for their alleged grafting during the "Škoda Affair", which had profited the Polish industrialist Bruno Seletzky. However, Minuț notes, Goga was "contradictory" even at this late stage, sometimes stating his belief in the minorities' integration, but often decrying their participation in public life.[56]

The PNA nevertheless had at least three Jewish affiliates: the Vianus, who probably believed that membership would compliment their assimilation,[26] and journalist Henric Streitman, who was primarily motivated by anticommunism.[57] While Tudor Vianu co-chaired the PNA Studies Circle, alongside Petrovici,[58] Streitman was appointed on the PNA's Executive Committee.[57]

The party remained open to other ethnic minorities: its branch in Durostor County, organized by M. Magiari and Pericle Papahagi, counted Turks, Bulgarians and Aromanians among its members.[12] PNA sections in Bukovina were led by Petro Ivanciuc, Andriv Zemliuc and Necolai Palli, who were probably Ukrainian.[59] Goga also had contacts within the Romani community, including activist Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică, who acted as an electoral agent for both the PNA and the Iron Guard.[60] This issue highlighted the schism between the two Romani organizations, respectively led by Lăzăreanu and Calinic Șerboianu. At the time, Șerboianu accused his rival of being Goga's puppet.[61]

Elections

According to Heinen, the PNA can be grouped into an "antisemitic [and] markedly right-wing" segment, alongside the LANC and the Citizen Bloc—but distinct from the more radical Iron Guard. The three parties had 9% of the vote in the July 1932 election, with the PNA itself at 3.64%[62] (or 4% and 108,857 ballots, in Minuț's count).[63] The leading candidates included Dragomir, Ghițescu, Gorun, Ioanid, Lupaș, Nemoianu, Scridon, Valjean, Sergiu Niță, I. C. Atanasiu, Dumitru Topciu, as well as the party leader and his brother Eugen Goga. Eight were elected, including Octavian Goga for Mureș, Ioanid for Mehedinți, Ghițescu for Teleorman, Pavel Cuciujna for Orhei, and Valjean for Romanați;[64] Scridon also entered the Assembly by taking the second seat in Năsăud County, with 2,069 votes.[65] According to Netea's first-hand account, Goga's victory was hard-won: peasants rounded up to mock him during his campaign tour at Deda.[66]

Speaking for his party, Ghițescu accused Premier Vaida of having falsified the vote.[67] The PNA chose not to compete in the by-elections of September, announcing that it was too caught up organizing its base. Vaida's paper, Gazeta Transilvaniei, ridiculed this decision, noting that Goga had been "shamed" and was not risking further embarrassment.[68] In December, Carol asked Vaida to step down, and the National Liberals took over, with Ion G. Duca at the helm. Duca then approached the PNA leadership to establish a coalition, conditioned on Goga toning down his nationalism; Goga refused.[69] The National Agrianists had cultivated a relationship with two other splinter groups of the classical parties: the Georgist Liberal Party and the Lupist Peasantists. It developed into a working alliance.[70]

On June 26, 1933, the PNA held a large rally on a high plain outside Târgoviște. Goga used this venue to announce his contempt for the PNȚ, describing its leader, Iuliu Maniu, as "responsible for all misfortunes that have fallen upon this country."[71] The 1932 performance was closely mirrored in the December 1933 election, when the PNA managed 4.1%, with its family of parties again at 9%.[72] The PNA had nine mandates: Goga, Scridon, Ioanid and Ghițescu held on to their seats; Valjean was also elected, but for Caraș, with Petrovici taking his post in Romanați.[73] Topciu also won a seat, at Tighina, while physician Gheorghe Banu was elected at Ialomița. Another new recruit, Vasile Goldiș, failed to win the race for Arad, as did Ion Demetrescu-Agraru in Baia, while Lupaș lost at Sibiu and Nemoianu at Severin.[74] Overall, the PNA had some 122,000 votes, which was enough to earn it an extra seat.[75]

Between these two races, Germany had come under Nazi control, and the PNA found itself intensely courted by the new regime, which pursued Eastern European alliances. Goga was a regular guest at the German Legation, and accepted offers for collaboration; however, he also insisted that Nazi Germany vouch for Greater Romania's borders.[76] During those months, the PNA, represented by Valjean, joined the "Antirevisionist League", a civic movement for the Little Entente and against Hungarian irredentism.[77] In its electoral program of 1933, the PNA proposed measures to supervise Romania's minorities, and in particular their "ideological imports".[78]

Nonetheless, in March 1933, the Nazi agent of influence, Friedrich Weber, described Goga as a "man of the future", one who could bring the ideology to Romania.[79] A far-right politico, Nae Ionescu, allegedly regarded Goga as a potential Prime Minister of an Iron Guard cabinet. According to this version, Goga was tasked with enacting the "Hitlerian" program, including antisemitism and anti-Masonry.[80] This pronouncement anticipated Goga's own departure from the Romanian Freemasonry, of which he was still a member in summer 1933.[81] In September, Goga and Ștefan Tătărescu of the Romanian National Socialists were both received by Hitler in Berlin.[82] As historian Francisco Veiga notes, visits to Germany and the Kingdom of Italy made Goga "enthusiastic" and "completed [his] political evolution".[83]

Merger and splinters

The PNA and the LANC both repeatedly tried, but failed, to persuade the Iron Guard into a merger.[84] King Carol also proposed that the Guard be co-opted into a government coalition of "national forces", centered on the PP and the PNA.[85] This tendency was curbed by Premier Duca, who outlawed the Guard. Goga and the PNA reacted with public protests, viewing the measure as unwarranted.[86] Reportedly, after Duca's assassination by Guardist Nicadori, Goga sent boots to all those convicted for the murder.[87] PNA deputies publicly called for an end to the anti-Guard wave of arrests, suggesting that it was unjustified.[88] Nevertheless, according to writer Al. Gherghel, in August 1933 the PNA still viewed itself as standing against "right- and left-wing extremes", its platform one of "moderate progress".[39] In mid 1935, Goga also approached Vaida's new far-right party, called Romanian Front (FR), with offers of alliance or merger. Reportedly, Goga offered to fuse the PNA group into the FR, asking that he be assigned vice-chairmanship; Vaida refused, since he had promised that role to a long-time collaborator of his, Aurel Vlad.[89]

The National Agrarianists held their second and final congress on April 7, 1935, again at Rio Cinema.[90] On July 14,[91] the PNA merged with the LANC to form the National Christian Party, a hard-line antisemitic group. It used as its most popular symbol the LANC swastika, which Goga himself acknowledged as standing for the "Aryan race".[92] This new party had a shared presidency, with Cuza and Goga as co-chairs. It sought to challenge the Iron Guard whilst remaining close to more mainstream conservative forces.[93] The merger was partly motivated by Cuza's political calculations, since the LANC had only taken 4.5% of the vote in 1933.[48] Nichifor Crainic, who oversaw the LANC's paramilitary youth (or Lăncieri), boasted an important role in negotiating the Goga–Cuza rapprochement.[94] However, as Heinen suggests, Carol was also directly involved in pushing for the merger.[95] Additional pressure had come from the office of Alfred Rosenberg in Nazi Germany, where a stronger antisemitic party in Romania was seen as desirable.[96]

As noted by historian Lucian T. Butaru, Goga proved a worthy replacement for Cuza's first associate, Nicolae Paulescu, who had died after disease in 1931.[97] Nevertheless, the new party faced immediate difficulties. A far-left antifascist, Scarlat Callimachi, noted in September 1935 that the PNC was made up from regional chapters that had no common ideological ground, the entire enterprise having been engineered by Hitler.[98] The fusion resulted in another split: after being sidelined in favor of a Goga favorite, Ion V. Emilian quit the PNC and formed his own movement, called "Fire Swastika".[99] Valjean also opposed the merger, and made a point of not attending the PNC's constitutive congress.[100] His own National Agrarian Party, centered on Romanați, counted among its members poet Horia Furtună, sculptor Dumitru Pavelescu-Dimo, and businessman Sterie Ionescu (formerly of the League Against Usury).[41] Valjean's party still existed during the general election of December 1937, when it ran under a "T" logo, the old PNA symbol having been withdrawn and made unavailable for use.[101]

Of the PNA moderates, Lupaș no longer joined the PNC, whereas his colleague Dragomir did.[102] Tudor Vianu left before the unification and the adoption of full-on antisemitism,[26] with his brother resigning in 1935;[27] by contrast, Streitman remained an outside ally, serving as the PNC's electoral agent.[57] Goga himself became more explicitly antisemitic. Appointed Carol's Prime Minister after the 1937 election, he introduced a set of antisemitic laws. However, he continued to view himself as a moderate, censuring PNC radicals—including Gheorghe Cuza, who took pride in fomenting violence.[103] Virulent antisemitism was also embraced by the Romani caucus of Craiova, whose leader, Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică, finally joined the PNC in February 1938.[104]

Notes

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 267–268

- ↑ Netea, p. 249

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 268–269

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 269

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 269; Moldovan, pp. 273–275

- ↑ Heinen, p. 175

- ↑ Butaru, p. 102; Netea, p. 187

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 273

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 269

- ↑ Moldovan, pp. 274–275

- ↑ Heinen, p. 172

- 1 2 Tr. R., "Știri—Note—Comentarii. Marea întrunire Național-Agrară ținută la Turtucaia", in Farul, Issue 14/1933, p. 4

- ↑ Moldovan, p. 306

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 273, 274; Nastasă, p. 87. See also Netea, p. 249

- ↑ Netea, p. 249

- 1 2 Hans-Christian Maner, "Despre elite și partide politice din România interbelică", in Vasile Ciobanu, Sorin Radu (eds.), Partide politice și minorități naționale din România în secolul XX, Vol. III, p. 197. Sibiu: TechnoMedia, 2008. ISBN 978-973-739-261-9

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 270

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 272–273

- ↑ Radu, p. 578

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 274; Netea, p. 250

- ↑ Radu, pp. 578–579

- ↑ "Conștiința Ardealului. Glasul vremii îndreaptă lumea pe calea adevărului", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 50/1932, p. 1

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 273

- ↑ Netea, pp. 249–250

- ↑ Adriana Gagea, "Virgil Molin – un tipograf și ziarist de excepție (27 nov. 1898 – 28 ian. 1968)", in Biblioteca Bucureștilor, Issue 11/1998, pp. 34–35

- 1 2 3 Lucian Boia, Capcanele istoriei. Elita intelectuală românească între 1930 și 1950, pp. 102–103. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2012. ISBN 978-973-50-3533-4

- 1 2 Emilia Motoranu, "Un scriitor uitat: Alexandru Vianu", in Sud. Revistă Editată de Asociația pentru Cultură și Tradiție Istorică Bolintineanu, Issues 1–2/2016, p. 5

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 274

- ↑ Ileana-Stanca Desa, Elena Ioana Mălușanu, Cornelia Luminița Radu, Iuliana Sulică, Publicațiile periodice românești (ziare, gazete, reviste). Vol. V: Catalog alfabetic 1930–1935, pp. 30, 121, 260, 266, 364. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 2009. ISBN 978-973-27-1828-5. See also Minuț (1999), p. 274

- ↑ Heinen, p. 175

- ↑ Payne, pp. 279, 284

- ↑ Heinen, p. 18

- ↑ Heinen, p. 175

- ↑ Livezeanu, p. 218

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 142–143, 175

- ↑ Levy et al., p. 279; Veiga, p. 201

- ↑ Heinen, p. 160

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 427

- 1 2 Al. Gherghel, "Octavian Goga și partidul său", in Farul, Issue 18/1933, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Heinen, p. 160; Minuț (2001), pp. 424–425

- 1 2 Dumitru Botar, "Din presa romanațeană de altădată (III)", in Memoria Oltului și Romanaților, Issue 4/2017, p. 32

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 270–271 & (2001), pp. 425, 427

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 271

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 425, 427

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 429

- ↑ Oltea Rășcanu Gramaticu, "Viața politică interbelică în județul Tutova", in Acta Moldaviae Meridionalis, Vol. XXXVI, 2015, p. 295

- ↑ Cornel Popescu, George Daniel Ungureanu, "Romanian Peasantry and Bulgarian Agrarianism in the Interwar Period: Benchmarks for a Comparative Analysis", in The Romanian Review of Social Sciences, Issue 16, 2014, p. 48

- 1 2 William I. Brustein, Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust, p. 157. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-77478-0

- ↑ Heinen, p. 85; Veiga, pp. 133–134

- ↑ Butaru, p. 161; Heinen, pp. 111, 161–162; Livezeanu, pp. 230–231

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 160, 161–162

- ↑ Livezeanu, pp. 230–231

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 112–113, 115–116, 161

- ↑ Butaru, p. 271

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 272

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 423–424, 426

- 1 2 3 (in Romanian) G. Brătescu, "Uniunea Ziariștilor Profesioniști, 1919 – 2009. Compendiu aniversar", in Mesagerul de Bistrița-Năsăud, December 11, 2009

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 273–274

- ↑ Florin-Răzvan Mihai, "Dinamica electorală a candidaților minoritari din Bucovina la alegerile generale din România interbelică", in Vasile Ciobanu, Sorin Radu (eds.), Partide politice și minorități naționale din România în secolul XX, Vol. V, pp. 96, 100. Sibiu: TechnoMedia. ISBN 978-973-739-261-9

- ↑ Oprescu, pp. 32–33; Varga, p. 631

- ↑ Varga, p. 631

- ↑ Heinen, p. 153

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 274

- ↑ Minuț (1999), pp. 274–275

- ↑ Moldovan, pp. 276–277, 306

- ↑ Netea, pp. 250–252

- ↑ Minuț (1999), p. 275

- ↑ "Sunt acri strugurii. Gogiștii nu candidează la alegerile parțiale", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 70/1932, p. 4

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 426

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 430

- ↑ "Intrunirea gogistă dela Târgoviște", in Adevĕrul, June 27, 1933, p. 5

- ↑ Heinen, p. 153; Minuț (2001), p. 428

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 427–428

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 427–428

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 428, 430

- ↑ Heinen, p. 222

- ↑ Livia Dandara, "Considerații privind fondarea Ligii antirevizioniste române", in Memoria Antiquitatis (Acta Musei Petrodavensis), Vols. XV–XVII, 1987, pp. 209–211

- ↑ Minuț (2001), pp. 426–427

- ↑ Heinen, p. 227

- ↑ Veiga, p. 201

- ↑ Nastasă, p. 103

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 228, 230

- ↑ Veiga, p. 134

- ↑ Heinen, p. 249

- ↑ Veiga, p. 202

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 430

- ↑ Clark, p. 113

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 429

- ↑ Netea, pp. 253–254

- ↑ Minuț (2001), p. 430

- ↑ Butaru, p. 102; Minuț (1999), p. 275

- ↑ Radu, pp. 583–584

- ↑ Payne, p. 284

- ↑ Clark, pp. 117–118

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 242, 249

- ↑ Clark, p. 117; Levy, p. 158. See also Heinen, p. 249

- ↑ Butaru, p. 102

- ↑ Ion Maximiuc, "Publiciști de vază în ziarul Clopotul din Botoșani", in Hierasus, Vol. VI, 1986, p. 190

- ↑ Clark, p. 118; Heinen, p. 250; Veiga, p. 215

- ↑ "Ziarul Porunca Vremii scrie", in Înainte, Issue 7/1935, p. 1

- ↑ See list published alongside N. Papatansiu, "Războiul electoral", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Issue 569, December 1937, p. 6

- ↑ Nastasă, p. 87

- ↑ Butaru, pp. 271–272

- ↑ Oprescu, p. 33; Varga, pp. 633–634

References

- Lucian T. Butaru, Rasism românesc. Componenta rasială a discursului antisemit din România, până la Al Doilea Război Mondial. Cluj-Napoca: EFES, 2010. ISBN 978-606-526-051-1

- Roland Clark, "Nationalism and Orthodoxy: Nichifor Crainic and the Political Culture of the Extreme Right in 1930s Romania", in Nationalities Papers, Vol. 40, Issue 1, January 2012, pp. 107–126.

- Armin Heinen, Legiunea 'Arhanghelul Mihail': o contribuție la problema fascismului internațional. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2006. ISBN 973-50-1158-1

- Richard S. Levy et al., Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1: A–K. Santa Barbara etc.: ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-439-3

- Irina Livezeanu, "Fascists and Conservatives in Romania: Two Generations of Nationalists", in Martin Blinkhorn (ed.), Fascists and Conservatives: The Radical Right and the Establishment in Twentieth-century Europe, pp. 218–239. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, 2003. ISBN 0-203-39605-7

- Adolf Minuț,

- "Întemeierea Partidului Național Agrar (1932)", in Acta Moldaviae Meridionalis, Vol. XXI, 1999–2000, pp. 267–277.

- "Activitatea Partidului Național Agrar (1932—1935)", in Acta Moldaviae Meridionalis, Vols. XXII–XXIII, Part I, 2001–2003, pp. 423–432.

- Victor Moldovan, Memoriile unui politician din perioada interbelică. Vol. I. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană, 2016. ISBN 978-973-595-971-5

- Lucian Nastasă, "Suveranii" universităților românești. Mecanisme de selecție și promovare a elitei intelectuale, Vol. I. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Limes, 2007. ISBN 978-973-726-278-3

- Vasile Netea, Memorii. Târgu Mureș: Editura Nico, 2010. ISBN 978-606-546-049-2

- Dan Oprescu, "Minoritățile naționale din România. O privire din avion", in Sfera Politicii, Issue 4 (158), April 2011, pp. 29–43.

- Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914–45. London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0-203-80956-4

- Sorin Radu, "Semnele electorale ale partidelor politice în perioada interbelică", in Anuarul Apulum, Vol. XXXIX, 2002, pp. 574–586.

- Andrea Varga, "În loc de concluzii", in Lucian Nastasă, Andrea Varga (eds.), Minorități etnoculturale. Mărturii documentare. Țiganii din România (1919–1944), pp. 627–643. Cluj-Napoca: Fundația CRDE, 2001. ISBN 973-85305-2-0