Credit union

| Part of a series on financial services |

| Banking |

|---|

|

Types of banks

|

|

Funds transfer |

|

A credit union is a member-owned financial cooperative, controlled by its members and operated on the principle of people helping people, providing its members credit at competitive rates as well as other financial services.[1][2]

Worldwide, credit union systems vary significantly in terms of total assets and average institution asset size, ranging from volunteer operations with a handful of members to institutions with assets worth several billion U.S. dollars and hundreds of thousands of members.[3] Credit unions operate alongside other mutuals and cooperatives engaging in cooperative banking, such as building societies.

"Natural-person credit unions" (also called "retail credit unions" or "consumer credit unions") serve individuals, as distinguished from "corporate credit unions", which serve other credit unions.[4][5][6]

Differences from other financial institutions

Credit unions differ from banks and other financial institutions in that those who have accounts in the credit union are its members and owners,[1] and they elect their board of directors in a one-person-one-vote system regardless of their amount invested.[1] Credit unions see themselves as different from mainstream banks, with a mission to be "community-oriented" and "serve people, not profit".[7][8][9]

Credit unions offer many of the same financial services as banks, but often use a different terminology. Typical services include share accounts (savings accounts), share draft accounts (checking accounts), credit cards, share term certificates (certificates of deposit), and online banking. Normally, only a member of a credit union may deposit or borrow money.[1] Surveys of customers at banks and credit unions have consistently shown significantly higher customer satisfaction rates with the quality of service at credit unions.[10][11] Credit unions have historically claimed to provide superior member service and to be committed to helping members improve their financial situation. In the context of financial inclusion credit unions claim to provide a broader range of loan and savings products at a much cheaper cost to their members than do most microfinance institutions.[12]

Not-for-profit status

In the credit union context, "not-for-profit" must be distinguished from a charity.[13] Credit unions are "not-for-profit" because their purpose is to serve their members rather than to maximize profits,[12][12][13] so, unlike charities and the like, credit unions do not rely on donations, and are financial institutions that must make what is, in economic terms, a small profit (i.e., in non-profit accounting terms, a "surplus") to remain in existence.[12][14] According to the World Council of Credit Unions (WOCCU), a credit union's revenues (from loans and investments) must exceed its operating expenses and dividends (interest paid on deposits) in order to maintain capital and solvency.[14]

In the United States, credit unions incorporated and operating under a state credit union law are tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(14)(A).[15] Federal credit unions organized and operated in accordance with the Federal Credit Union Act are tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(1).[16]

Global presence

According to the World Council of Credit Unions (WOCCU), at the end of 2014 there were 57,480 credit unions in 105 countries. Collectively they served 217.4 million members and oversaw US$1.79 trillion in assets.[17] WOCCU does not include data from cooperative banks, so, for example, some countries generally seen as the pioneers of credit unionism, such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy, are not always included in their data. The European Association of Co-operative Banks reported 38 million members in those four countries at the end of 2010.[18]

The countries with the most credit union activity are highly diverse. According to WOCCU, the countries with the greatest number of credit union members were the United States (101 million), India (20 million), Canada (10 million), Brazil (6.0 million), South Korea (5.7 million), Philippines (5.4 million), Kenya and Mexico (5.1 million each), Ecuador (4.8 million), Australia (4.5 million), Thailand (4.1 million), Colombia (3.6 million) and Ireland (3.3 million).[17]

The countries with the highest percentage of credit union members in the economically active population were Barbados (82%),[19] Ireland (75%), Grenada (72%), Trinidad & Tobago (68%), Belize and St. Lucia (67% each), St. Kitts & Nevis (58%), Jamaica (53% each), Antigua and Barbuda (49%), the United States (48%), Ecuador (47%), and Canada (43%). Several African and Latin American countries also had high credit union membership rates, as did Australia and South Korea. The average percentage for all countries considered in the report was 8.2%.[17] Credit unions were launched in Poland in 1992; as of 2012 there were 2,000 credit union branches there with 2.2 million members.[20]

History

Modern credit union history dates from 1852, when Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch consolidated the learning from two pilot projects, one in Eilenburg and the other in Delitzsch in the Kingdom of Saxony into what are generally recognized as the first credit unions in the world. He went on to develop a highly successful urban credit union system.[21] In 1864 Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen founded the first rural credit union in Heddesdorf (now part of Neuwied) in Germany.[21] By the time of Raiffeisen's death in 1888, credit unions had spread to Italy, France, the Netherlands, England, Austria, and other nations.[22]

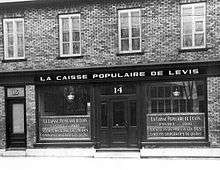

The first credit union in North America, the Caisse Populaire de Lévis in Quebec, Canada, began operations on January 23, 1901 with a 10-cent deposit. Founder Alphonse Desjardins, a reporter in the Canadian parliament, was moved to take up his mission in 1897 when he learned of a Montrealer who had been ordered by the court to pay nearly C$5,000 in interest on a loan of $150 from a moneylender. Drawing extensively on European precedents, Desjardins developed a unique parish-based model for Quebec: the caisse populaire.

In the United States, St. Mary's Bank Credit Union of Manchester, New Hampshire, was the first credit union. Assisted by a personal visit from Desjardins, St. Mary's was founded by French-speaking immigrants to Manchester from Quebec on November 24, 1908. Several Little Canadas throughout New England formed similar credit unions, often out of necessity, as Anglo-American banks frequently Franco-Americans loans.[23] America's Credit Union Museum now occupies the location of the home from which St. Mary's Bank Credit Union first operated. On November 1910 the Woman's Educational and Industrial Union set up the Industrial Credit Union, modeled on the Desjardins credit unions it was the first non-faith-based community credit union serving all people in the greater Boston area. The oldest statewide credit union in the United States was established in 1913. The St. Mary's Bank Credit Union serves any resident of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[24]

After being promoted by the Catholic Church in the 1940s to assist the poor in Latin America, credit unions expanded rapidly during the 1950s and 1960s, especially in Bolivia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Peru. The Regional Confederation of Latin American Credit Unions (COLAC) was formed and with funding by the Inter-American Development Bank credit unions in the regions grew rapidly throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s. In 1988 COLAC credit unions represented 4 million members across 17 countries with a loan portfolio of circa half a billion US dollars. However, from the late 1970s onwards many Latin American credit unions struggled with inflation, stagnating membership and serious loan recovery problems. In the 1980s donor agencies such as USAID attempted to rehabilitate Latin American credit unions by providing technical assistance and focusing credit unions' efforts on mobilising deposits from the local population. In 1987 the regional financial crisis caused a run on credit unions. Significant withdrawals and high default rates caused liquidity problems for many credit unions in the region.[25]

Stability and risks

Credit unions and banks in most jurisdictions are legally required to maintain a reserve requirement of assets to liabilities. If a credit union or traditional bank is unable to maintain positive cash flow and/or is forced to declare insolvency, its assets are distributed to creditors (including depositors) in order of seniority according to bankruptcy law. If the total deposits exceed the assets remaining after more senior creditors are paid, all depositors will lose some or all of their initial deposits. However, most jurisdictions have deposit insurance that promises to make depositors whole up to a maximum insurable account level. In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 there was a dramatic increase in the number of bank failures but not in the number of credit union failures, and in 2017 all depositors at failed credit unions were fully covered by deposit insurance but depositors at a failed traditional bank were not covered by deposit insurance.[26]

Corporate

Credit unions as such provide service only to individual consumers. Corporate credit unions (also known as central credit unions in Canada) provide service to credit unions, with operational support, funds clearing tasks, and product and service delivery.

Leagues and associations

Credit unions often form cooperatives among themselves to provide services to members. A credit union service organization (CUSO) is generally a for-profit subsidiary of one or more credit unions formed for this purpose. For example, CO-OP Financial Services, the largest credit-union-owned interbank network in the United States, provides an ATM network and shared branching services to credit unions. Other examples of cooperatives among credit unions include credit counseling services as well as insurance and investment services.

State credit union leagues can partner with outside organizations to promote initiatives for credit unions or customers. For example, the Indiana Credit Union League sponsors an initiative called "Ignite", which is used to encourage innovation in the credit union industry, with the Filene Research Institute.[27]

The World Council of Credit Unions (WOCCU) is both a trade association for credit unions worldwide and a development agency. The WOCCU's mission is to "assist its members and potential members to organize, expand, improve and integrate credit unions and related institutions as effective instruments for the economic and social development of all people".[28]

The Credit Union National Association (CUNA) is a national trade association for both state- and federally chartered credit unions located in the United States. The National Credit Union Foundation is the primary charitable arm of the United States' credit union movement and an affiliate of CUNA.

Deposit insurance

In the United States, federal credit unions are chartered by and overseen by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), which also provides deposit insurance similar to the manner in which the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) provides deposit insurance to banks. State-Chartered credit unions are overseen by the state's financial regulation agency and may, but are not required to, obtain deposit insurance. Because of problems with bank failures in the past, no state provides deposit insurance and as such there are two primary sources for depository insurance – the NCUA and American Share Insurance (ASI), a private insurer based in Ohio.

In Canada, most credit unions are provincially incorporated and regulated, with deposit insurance provided by a provincial Crown corporation. For example, in Ontario, up to $250,000 of coverage is provided through the Deposit Insurance Corporation of Ontario.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "12 U.S.C. § 1752(1), CUNA Model Credit Union Act (2007)" (PDF). National Credit Union Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-09. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 511. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ↑ "Slide 1" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ↑ Frank J. Fabozzi & Mark B. Wickard, Credit Union Investment Management (1997), pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Wendell Cochran, "Credit unions pay for risky behavior by a few", NBC News (December 21, 2010).

- ↑ "Corporate System Resolution: Corporate Credit Unions: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)", National Credit Union Administration (September 24, 2010).

- ↑ "The Credit Union Difference". Credit Union National Association.

- ↑ Archived January 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Converts sing praises of credit unions". MSN Money. Archived from the original on 2012-03-09.

- ↑ Allred, Anthony T. & Adams, H. Lon (2000). "Service quality at banks and credit unions: what do their customers say?". Managing Service Quality. 10 (1).

- ↑ Allred, Anthony T. (2001). Employee evaluations of service quality at banks and credit unions. International Journal of Bank Marketing. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 "What is a Credit Union?". woccu.org.

- 1 2 "Not-for-profit", noun, Oxford English Dictionary (2008)

- 1 2 "WOCCU, "PEARLS: Ratios: R — Rate of Return and Costs & S — Signs of Growth". Woccu.org. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ↑ "Part 4. Examining Process: Chapter 76. Exempt Organizations Examination Guidelines: Section 22. Credit Unions — IRC 501(c)(14)". Internal Revenue Manual. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ↑ "Other Section 501(c) Organizations". Publication 557: Tax-exempt Status and Your Organization. Internal Revenue Service. February 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Statistical Report – World Council of Credit Unions". woccu.org.

- ↑ "European Association of Cooperative Banks, Annual Statistical Report, 2010". Eurocoopbanks.coop. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ↑ Percival, Geoff (March 19, 2012). "75% of Irish adults in credit unions". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012.

- ↑ Diekmann, Frank J. (July 2, 2012). "Poland's CUs: From Zero To Mature In Just 20 Yrs". Credit Union Journal. pp. 1, 22.

- 1 2 J. Carroll Moody & Gilbert C. Fite. The Credit Union Movement: Origins and Development 1850 to 1980. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co., Dubuque, Iowa, 1984

- ↑ Singh, S. K. (2009). Bank Regulations. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Bélanger, Damien-Claude. "French-Canadian Emigration to the United States, 1840-1930". Québec History. Marianopolis College. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ "St. Mary's Credit Union". Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ Bernd Balkenhol (1999). Credit Unions and the Poverty Challenge. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: International Labour Organization. pp. 45–47. ISBN 9789221108528.

- ↑ "Review of the 2017 Bank Failures and Their Effects on Depositors". Deposit Accounts. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ "Indiana credit union reps chosen to take part in ICUL ignite program for innovation". Bank Credit News. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10.

- ↑ "Mission". WOCCU. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

Further reading

- Ian MacPherson. Hands Around the Globe: A History of the International Credit Union Movement and the Role and Development of the World Council of Credit Unions, Inc. Horsdal & Schubart Publishers Ltd, 1999.

- F.W. Raiffeisen. The Credit Unions. Trans. by Konrad Engelmann. The Raiffeisen Printing and Publishing Company, Neuwid on the Rhine, Germany, 1970.

- Fountain, Wendell. The Credit Union World. AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4259-7006-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Credit unions. |

- Credit Union National Association national trade association for credit unions

- World Council of Credit Unions global trade association for credit unions

- Association of Asian Confederations of Credit Unions regional federation representing 21 national federations in Asia with 35 million retail members

- National Credit Union Service Organization directory of all credit unions in the U.S.

- National Credit Union Foundation charitable arm of credit union industry