King cobra

| King cobra | |

|---|---|

| |

| King cobra in Kaeng Krachan National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Ophiophagus Gunther, 1864 |

| Species: | O. hannah |

| Binomial name | |

| Ophiophagus hannah Cantor, 1836 | |

| |

Native distribution of the king cobra | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus-level:

| |

The king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), also known as the hamadryad, is a venomous snake species in the family Elapidae, endemic to forests from India through Southeast Asia. It is threatened by habitat destruction and has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 2010.[1] It is the world's longest venomous snake.[2] Adult king cobras are 3.18 to 4 m (10.4 to 13.1 ft) long. The longest known individual measured 5.85 m (19.2 ft).[3] Despite the word "cobra" in its common name, this species does not belong to genus Naja but is the sole member of its own. It preys chiefly on other snakes and occasionally on some other vertebrates, such as lizards and rodents. It is a dangerous snake that has a fearsome reputation in its range,[4][5][6] although it typically avoids confrontation with humans when possible.[4] The king cobra is a prominent symbol in the mythology and folk traditions of India, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.[7][8] It is the national reptile of India.[9]

Taxonomy

The king cobra was described and drawn by the Danish naturalist Theodore Edward Cantor in 1836, who gave it the scientific name Hamadryas hannah. Cantor had three specimens from the Sundarbans and one caught in the vicinity of Kolkata.[10] It was subordinated to the genus Ophiophagus by Albert Günther in 1864.[11]

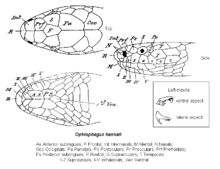

Ophiophagus hannah belongs to the monotypic genus Ophiophagus in the family Elapidae, while most other cobras are members of the genus Naja. They can be distinguished from other cobras by size and hood. King cobras are generally larger than other cobras, and the stripe on the neck is a chevron instead of a double or single eye shape that may be seen in most of the other Asian cobras. Moreover, the hood of the king cobra is narrower and longer.[4] A key to identification, clearly visible on the head, is the presence of a pair of large scales known as occipitals, located at the back of the top of the head. These are behind the usual "nine-plate" arrangement typical of colubrids and elapids, and are unique to the king cobra.

Description

The skin of king cobra is dark olive or brown with black bands and white or yellow crossbands. The head is black with two crossbars near the snout and two behind the eyes. Adult king cobras are 3.18 to 4 m (10.4 to 13.1 ft) long. The longest known individual measured 5.85 m (19.2 ft).[3] Its belly is cream or pale yellow.[12] It has 17 to 19 rows of smooth scales. Ventral scales are uniformly oval shaped. Dorsal scales are placed in an oblique arrangement.[13] Males have 235 to 250 ventral scales, while females have 239 to 265. The subcaudal scales are single or paired in each row, numbering 83 to 96 in males and 77 to 98 in females.

Juveniles are shiny black with narrow yellow bands (can be mistaken for a banded krait, but readily identified with its expandable hood). The head of a mature snake can be quite massive and bulky in appearance, though like all snakes, it can expand its jaws to swallow large prey items. It has proteroglyph dentition, meaning it has two short, fixed fangs in the front of the mouth, which channel venom into the prey like hypodermic needles. The average lifespan of a wild king cobra is about 20 years.[12]

King cobras are sexually dimorphic in size, with males reaching larger sizes than females, which is an unusual trait among snakes whose females are usually larger than males. The length and mass of the snakes highly depend on their localities and some other factors.

The king cobra typically weighs about 6 kg (13 lb). The longest known specimen was a captive one at the London Zoo, and grew to around 18.5 to 18.8 ft (5.6 to 5.7 m) before being euthanised upon the outbreak of World War II. The heaviest wild specimen was caught at Royal Island Club in Singapore in 1951, which weighed 12 kg (26 lb) and measured 4.8 m (16 ft), though an even heavier captive specimen was kept at New York Zoological Park and was measured as 12.7 kg (28 lb) at 4.4 m (14.4 ft) long in 1972. Some viper species, such as the eastern diamondback rattlesnake and the Gaboon viper, often much shorter in length but bulkier in build, rival the king cobra in average weight.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The king cobra is distributed across the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and the southern areas of East Asia (where it is not common), in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and southern China.[1] In India it has been recorded from Goa; Western Ghats of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu; east coastline of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha; Sundarban mangroves; Himalayan foothills from Uttrakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, northern parts of West Bengal to most of the north-east region and Andaman Islands. Type locality Sundarbans. [15]It lives in dense highland forests,[2][16] preferring areas dotted with lakes and streams. King cobra populations have dropped in some areas of its range because of the destruction of forests and ongoing collection for the international pet trade. It is listed as an Appendix II animal within CITES.[17]

Behavior

A king cobra, like other snakes, receives chemical information via its forked tongue, which picks up scent particles and transfers them to a special sensory receptor (Jacobson's organ) located in the roof of its mouth.[2] This is akin to the human sense of smell. When the scent of a meal is detected, the snake flicks its tongue to gauge the prey's location (the twin forks of the tongue acting in stereo); it also uses its keen eyesight; king cobras are able to detect moving prey almost 100 m (330 ft) away. Its intelligence[18] and sensitivity to earth-borne vibration are also used to track its prey.

Following envenomation, the king cobra swallows its struggling prey. King cobras, like all snakes, have flexible jaws. The jaw bones are connected by pliable ligaments, enabling the lower jaw bones to move independently. This allows the king cobra to swallow its prey whole, and swallow prey much larger than its head.[2]

King cobras are able to hunt throughout the day, but are rarely seen at night, leading most herpetologists to classify them as a diurnal species.[2][19]

Feeding ecology

The king cobra's generic name, Ophiophagus is a Greek-derived word that means "snake-eater". Its diet consists primarily of other snakes, including rat snakes, pythons, and even other venomous snakes such as various members of the true cobras and the krait.[19][20] Its most common prey is the rat snake, and it also hunts Malabar pit viper and hump-nosed pit viper by following the snakes' odour trails.[21]

When food is scarce, it also feeds on other small vertebrates, such as lizards, birds, and rodents. In some cases, the cobra constricts its prey, such as birds and larger rodents, using its muscular body, though this is uncommon.[2][20] After a large meal, the snake lives for many months without another one because of its slow metabolic rate.[2]

Defense

When annoyed, this species quickly attempts to escape and avoid confrontation.[6][22] However, if continuously provoked, the king cobra can be highly aggressive.[6][12]

When alarmed, it rears up the anterior portion (usually one-third) of its body when extending the neck, showing the fangs and hissing loudly.[4][12] It can be easily irritated by closely approaching objects or sudden movements. When raising its body, the king cobra can still move forward to strike with a long distance[12] and people may misjudge the safe zone. This snake can deliver multiple bites in a single attack,[5] and adults are known to bite and hold on. Many victims bitten by king cobras are actually snake charmers.[4]

Some scientists believe that the temperament of this species has been grossly exaggerated. In most of the local encounters with live, wild king cobras, the snakes appear to be of rather placid disposition, and they usually end up being killed or subdued with hardly any hysterics. These support the view that wild king cobras generally have a mild temperament, and despite their frequent occurrence in disturbed and built-up areas, are adept at avoiding humans. Naturalist Michael Wilmer Forbes Tweedie felt that "this notion is based on the general tendency to dramatise all attributes of snakes with little regard for the truth about them. A moment’s reflection shows that this must be so, for the species is not uncommon, even in populated areas, and consciously or unconsciously, people must encounter king cobras quite frequently. If the snake were really habitually aggressive, records of its bite would be frequent; as it is they are extremely rare."[23][24]

If a king cobra encounters a natural predator, such as the mongoose, which has resistance to the neurotoxins,[25] the snake generally tries to flee. If unable to do so, it forms the distinctive cobra hood and emits a hiss, sometimes with feigned closed-mouth strikes. These efforts usually prove to be very effective, especially since it is much more dangerous than other mongoose prey, as well as being much too large for the small mammal to kill with ease.

A good defense for anyone who accidentally encounters this snake is to slowly remove a shirt or hat and toss it to the ground while backing away.[26]

Growling hiss

The hiss of the king cobra is a much lower pitch than many other snakes and many people thus liken its call to a "growl" rather than a hiss. While the hisses of most snakes are of a broad-frequency span ranging from roughly 3,000 to 13,000 Hz with a dominant frequency near 7,500 Hz, king cobra growls consist solely of frequencies below 2,500 Hz, with a dominant frequency near 600 Hz, a much lower-sounding frequency closer to that of a human voice. Comparative anatomical morphometric analysis has led to a discovery of tracheal diverticula that function as low-frequency resonating chambers in king cobra and its prey, the rat snake, both of which can make similar growls.[27]

Reproduction

The female is gravid for 50 to 59 days, after which she builds a nest, lays 12 to 51 eggs and guards it during the incubation period of about 51 to 79 days. The hatchlings are 31 to 73 cm (12 to 29 in) long and weigh 18.4 to 40 g (0.65 to 1.41 oz).[3]

The king cobra is unusual among snakes in that the female is a very dedicated parent. For the nest, the female scrapes up leaves and other debris into a mound, and stays in the nest until the young hatch. She guards the mound tenaciously, rearing up into a threat display if any large animal gets too close.[28] Inside the mound, the eggs are incubated at a steady 28 °C (82 °F). When the eggs start to hatch, the female leaves the nest. The baby king cobra's venom is as potent as that of the adults. They may be brightly marked, but these colours often fade as they mature. They are alert and nervous, being highly aggressive if disturbed.[4]

Venom

The venom of the king cobra consists primarily of neurotoxins, known as the haditoxin,[29] with several other compounds.[19][30] Its murine LD50 toxicity varies from intravenous 1.31 mg/kg[31] and intraperitoneal 1.644 mg/kg[31] to subcutaneous 1.7—1.93 mg/kg.[32][33][34]

This species is capable of delivering a fatal bite and the victim may receive a large quantity of venom with a dose of 200 to 500 mg [4][35][36] up to 7 ml.[12] Engelmann and Obst (1981) list the average venom yield at 420 mg (dry weight).[33] Accordingly, large quantities of antivenom may be needed to reverse the progression of symptoms developed if bitten by a king cobra.[5] The toxins affect the victim's central nervous system, resulting in severe pain, blurred vision, vertigo, drowsiness, and eventually paralysis. If the envenomation is serious, it progresses to cardiovascular collapse, and the victim falls into a coma. Death soon follows due to respiratory failure. Bites from a king cobra may result in a rapid fatality[4][5] which can be as early as 30 minutes after the envenomation.[5][37] The king cobra's envenomation was even recorded to be capable of killing elephants within hours.[38]

Two types of antivenom are made specifically to treat king cobra envenomations. The Red Cross in Thailand manufactures one, and the Central Research Institute in India manufactures the other; however, both are made in small quantities and, while available to order, are not widely stocked.[39] Ohanin, a protein component of the venom, causes hypolocomotion and hyperalgesia in mammals.[40] Other components have cardiotoxic,[41] cytotoxic and neurotoxic effects.[42] In Thailand, a concoction of alcohol and the ground root of turmeric is ingested, which has been clinically shown to create a strong resilience against the venom of the king cobra, and other snakes with neurotoxic venom.[43][44] Proper and immediate treatments are critical to avoid death. Successful precedents include a client who recovered and was discharged in 10 days after being treated by accurate antivenom and inpatient care.[37]

Snakebites from this species are rare, and most victims are snake handlers.[4] Not all king cobra bites result in envenomation, but they are often considered of medical importance.[45] Clinical mortality rates vary between different regions and depend on many factors, such as local medical advancement. A Thai survey reports 10 deaths out of 35 patients received for king cobra bites, whose fatality rate posed (28%) is higher than those of other cobra species.[46] Department of Clinical Toxinology in University of Adelaide gives this serpent a general untreated fatality rate of 50–60%, implying that the snake has about a half chance to deliver bites involving nonfatal quantities of venom.[32]

Conservation

The species is classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN due to pressure from harvesting for meat, skin and use in traditional medicine, and because of increasing loss of habitat to deforestation.[1] In India, king cobras are placed under Schedule II of Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (as amended) and a person guilty of killing the snake can be imprisoned for up to six years.[47]

Cultural significance

.jpg)

A ritual in Myanmar involves a king cobra and a female snake charmer. The charmer is a priestess who is usually tattooed with three pictograms and kisses the snake on the top of its head at the end of the ritual.[8][20] Members of the Pakokku clan tattoo themselves with ink mixed with cobra venom on their upper bodies in a weekly inoculation that potentially might protect them from the snake, though no scientific evidence supports this.[20][48]

Cobra stones or gems or pearls are believed to develop from the cobra's hood.[49]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Stuart, B.; Wogan, G.; Grismer, L.; Auliya, M.; Inger, R.F.; Lilley, R.; Chan-Ard, T.; Thy, N.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Srinivasulu, C. & Jelić, D. (2012). "Ophiophagus hannah". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T177540A1491874.en

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mehrtens, J. (1987). Living Snakes of the World. New York: Sterling. ISBN 0-8069-6461-8.

- 1 2 3 Chanhome, L., Cox, M.J., Vasaruchapong, T., Chaiyabutr, N. and Sitprija, V. (2011). "Characterization of venomous snakes of Thailand". Asian Biomedicine 5 (3): 311–328.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 O'Shea, M. (2008). Venomou snakes of the world. London, Cape Town, Sydney, Auckland: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-691-15023-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davidson, T. "Immediate First Aid". University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 Young, D. (1999). "Ophiophagus hannah". Animal Diversity Web.

the King Cobra is undoubtedly a very dangerous snake ("Behavior" section)

- ↑ Minton, S.A., Jr. and M.R. Minton (1980). Venomous reptiles. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- 1 2 Platt, S.G.; Ko, W.K. and Rainwater, T.R. (2012). "On the Cobra Cults of Myanmar (Burma)". Chicago Herpetological Society. 47(2): 17–20.

- ↑ "King Cobra - National Reptile of India". indiamapped.

- ↑ Cantor, T. E. (1836). "Sketch of an undescribed hooded serpent, with fangs and maxillar teeth". Asiatic Res 19: 87−93.

- ↑ Günther, A. C. L. G. (1864). "Ophiophagus, Gthr.". The Reptiles of British India. London: Ray Society. pp. 340−342.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "National geographic- KING COBRA".

They are fiercely aggressive when cornered (line 28–29); average life span in the wild: 20 years (fast facts)

- ↑ Martin, D.L. (2012). "Identification of Reptile Skin Products Using Scale Morphology". In J. E. Huffman, J. R. Wallace. Wildlife Forensics: Methods and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 161–199.

- ↑ Wood, G.L. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ↑ http://indiansnakes.org/content/king-cobra

- ↑ Miller, Harry (September 1970). "The Cobra, India's 'Good Snake'". National Geographic. 20: 393–409.

- ↑ "CITES List of animal species used in traditional medicine". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ↑ Philadelphia Zoo – King cobra. philadelphiazoo.org

- 1 2 3 Capula, Massimo; Behler (1989). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-69098-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Coborn, J. (1991). The Atlas of Snakes of the World. TFH Publications. pp. 30, 452. ISBN 978-0-86622-749-0.

- ↑ Bhaisare, D., Ramanuj, V., Shankar, P.G., Vittala, M., Goode, M. and Whitaker, R. (2010). Observations on a Wild King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), with emphasis on foraging and diet. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 17(2): 95–102.

- ↑ Cornett, Brandon (2012). King Cobra – Ophiophagus hannah. Reptile Knowledge

- ↑ Greene, H. W. (1997). Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. California, USA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520224876.

- ↑ Tweedie, M.W.F. (1983). The Snakes of Malaya. Singapore: Singapore National Printers Ltd. OCLC 686366097.

- ↑ Takacs, Zoltan. "Why the cobra is resistant to its own venom". Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ Hauser, S. King Cobras, the largest venomous snakes. sjonhauser.nl

- ↑ Young, Bruce A. (1991). "Morphological basis of "growling" in the king cobra, Ophiophagus hannah". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 260 (3): 275–87. doi:10.1002/jez.1402600302. PMID 1744612.

- ↑ Piper, R. (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33922-8.

- ↑ "King Cobra venom may lead to a new drug". United Press International. 2010.

- ↑ Roy, A; Zhou, X; Chong, MZ; d'Hoedt, D; Foo, CS; Rajagopalan, N; Nirthanan, S; Bertrand, D; Sivaraman, J; Kini, R. M. (2010). "Structural and Functional Characterization of a Novel Homodimeric Three-finger Neurotoxin from the Venom of Ophiophagus hannah (King Cobra)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (11): 8302–15. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.074161. PMC 2832981. PMID 20071329.

- 1 2 Séan Thomas & Eugene Griessel – Dec 1999. "LD50 (Archived)". Archived from the original on 1 February 2012.

- 1 2 "Ophiophagus hannah". University of Adelaide.

- 1 2 Engelmann, Wolf-Eberhard (1981). Snakes: Biology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Leipzig; English version NY, USA: Leipzig Publishing; English version published by Exeter Books (1982). p. 222. ISBN 0-89673-110-3.

- ↑ Handbook of clinical toxicology of animal venoms and poisons. 236. USA: CRC Press. 1995. ISBN 0-8493-4489-1.

- ↑ Snake of medical importance. Singapore: Venom and toxins research group. ISBN 9971-62-217-3.

- ↑ Carroll, S. B. (2010). "science-the king cobra". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Tin-Myint; Rai-Mra; Maung-Chit; Tun-Pe; Da Warrell (1991). "Bites by the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) in Myanmar: Successful treatment of severe neurotoxic envenoming". The Quarterly journal of Medicine. 80 (293): 751–762. PMID 1754675.

- ↑ Debra Bourne MA VetMB MRCVS. "Snake Bite in Elephants and Ferrets". Twycross Zoo. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Munich AntiVenom Index: Ophiophagus hannah". Munich Poison Center. MAVIN (Munich AntiVenom Index). 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ↑ Pung, Y.F.; Kumar, S.V.; Rajagopalan, N.; Fry, B.G.; Kumar, P.P.; Kini, R.M. (2006). "Ohanin, a novel protein from king cobra venom: Its cDNA and genomic organization". Gene. 371 (2): 246–56. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.12.002. PMID 16472942.

- ↑ Rajagopalan, N.; Pung, Y.F.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Wong, P.T.H.; Kumar, P.P.; Kini, R.M. (2007). "β-Cardiotoxin: A new three-finger toxin from Ophiophagus hannah (King Cobra) venom with beta-blocker activity". The FASEB Journal. 21 (13): 3685–3695. doi:10.1096/fj.07-8658com. PMID 17616557.

- ↑ Chang, L.-S.; Liou, J.-C.; Lin, S.-R.; Huang, H.-B. (2002). "Purification and characterization of a neurotoxin from the venom of Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra)". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 294 (3): 574–578. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00518-1. PMID 12056805.

- ↑ Ernst, Carl H.; Evelyn M. (2011). Venomous Reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico: Heloderma, Micruroides, Micrurus, Pelamis, Agkistrodon, Sistrurus. JHU Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-8018-9875-4.

- ↑ Salama, R.; Sattayasai, J.; Gande, A. K.; Sattayasai, N.; Davis, M.; Lattmann, E. (2012). "Identification and evaluation of agents isolated from traditionally used herbs against Ophiophagus hannah venom". Drug discoveries & therapeutics. 6 (1): 18–23.

- ↑ Mathew, Gera, JL, T. "Ophitoxaemia (Venomous snakebite)". MEDICINE ON-LINE. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ Norris MD, Robert L. "Cobra Envenomation". Medscape. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Sivakumar, B (2 July 2012). "King cobra under threat, put on red list". The Times of India – Chennai. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd.

- ↑ Murphy, J. C. (2010). Secrets of the Snake Charmer: Snakes in the 21st Century. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4502-2127-6.

- ↑ Harish, J. (1996). The Healing Power of Gemstones: In Tantra, Ayurveda, and Astrology. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books. pp. 55, 56. ISBN 9781620550793.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Ophiophagus hannah |