Hybrid beasts in folklore

Hybrid beasts appear in the folklore of a variety of cultures as legendary creatures.

In burial sites

Remains similar to those of mythological hybrids have been found in burial sites discovered by archaeologists. Known combinations include horse-cows, sheep-cows, and a six-legged sheep. The skeletons were formed by ancient peoples who joined together body parts from animal carcasses of different species. The practice is believed to have been done as an offering to their gods.[1]

Description

These forms' motifs appear across cultures in many mythologies around the world.

Such hybrids can be classified as partly human hybrids (such as mermaids or centaurs) or non-human hybrids combining two or more non-human animal species (such as the griffin or the chimera). Hybrids often originate as zoomorphic deities who, over time, are given an anthropomorphic aspect.

Paleolithic

Partly human hybrids appear in petroglyphs or cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic, in shamanistic or totemistic contexts. Ethnologist Ivar Lissner theorized that cave paintings of beings combining human and animal features were not physical representations of mythical hybrids, but were instead attempts to depict shamans in the process of acquiring the mental and spiritual attributes of various beasts or power animals.[2] Religious historian Mircea Eliade has observed that beliefs regarding animal identity and transformation into animals are widespread.[3] The iconography of the Vinca culture of Neolithic Europe in particular is noted for its frequent depiction of an owl-beaked "bird goddess".[4]

Ancient Egypt

Examples of humans with animal heads (theriocephaly) in the ancient Egyptian pantheon include jackal-headed Anubis, cobra-headed Amunet, lion-headed Sekhmet, falcon-headed Horus, etc. Most of these deities also have a purely zoomorphic and a purely anthropomorphic aspect, with the hybrid representation seeking to capture aspects of both of which at once. Similarly, the Gaulish Artio sculpture found in Berne shows a juxtaposition of a bear and a woman figure, interpreted as representations of the theriomorphic and the anthropomorphic aspect of the same goddess.

Non-human hybrids also appear in ancient Egyptian iconography as in Ammit (combining the crocodile, the lion, and the hippopotamus).

Ancient Middle East

Mythological hybrids became very popular in Luwian and Assyrian art of the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age. The angel (human with birds' wings, see winged genie) the mermaid (part human part fish, see Enki, Atargatis, Apkallu) and the Shedu all trace their origins to Assyro-Babylonian art. In Mesopotamian mythology the urmahlullu, or lion-man served as a guardian spirit, especially of bathrooms.[5][6]

The Old Babylonian Lilitu demon, particularly as shown in the Burney Relief (part-woman, part-owl) prefigures the harpy/siren motif.

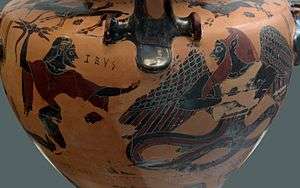

Mediterranean

In Archaic Greece, Luwian and Assyrian motifs were imitated, during the Orientalizing Period (9th to 8th centuries BC), inspiring the monsters of the mythology of the Classical Greek period, such as the Chimera, the Harpy, the Centaur, the Griffin, the Hippocampus, Talos, Pegasus, etc.

The motif of the winged man appears in the Assyrian winged genie, and is taken up in the Biblical Seraphim and Chayot, the Etruscan Vanth, Hellenistic Eros-Amor, and ultimately the Christian iconography of angels.

The motif of otherwise human figures sporting horns may derive from partly goat hybrids (as in Pan and the Devil in Christian iconography) or as partly bull hybrids (Minotaur). The Gundestrup cauldron and the Pashupati figure have stag's antlers (see also Horned God, horned helmet). The Christian representation of Moses with horns, however, is due to a mistranslation of the Hebrew text of Exodus 34:29–35 by Jerome.

Hinduism

The most prominent hybrid in Hindu iconography is elephant-headed Ganesha, god of wisdom, knowledge and new beginnings.

Both Nāga and Garuda are non-hybrid mythical animals (snake and bird, respectively) in their early attestations, but become partly human hybrids in later iconography.

The god Vishnu is believed to have taken his first four incarnations in human-animal form, namely: Matsya (human form with fish's body below waist), Kurma (human form with turtle's body below waist), Varaha (human form with a boar's head), Narasimha (human form with lion's head).

Kamadhenu, the mythical cow which is considered to be the mother of all other cattle is often portrayed as a cow with human head, peacock tail and bird wings.

Known mythological hybrids

See also

References

- ↑ Laura Geggel (July 21, 2015). "Horse-Cows? Bizarre 'Hybrid' Animals Found in Ancient Burials". LiveScience.

- ↑ Steiger, B. (1999). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shape-Shifting Beings. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink. ISBN 1-57859-078-7.

- ↑ Eliade, Mircea (1965). Rites and Symbols of Initiation: the mysteries of birth and rebirth. Harper & Row.

- ↑ a term of Marija Gimbutas', see e.g. The language of the goddess: unearthing the hidden symbols of western civilization San Francisco: Harper & Row; London: Thames and Hudson (1989).

- ↑ Black, Jeremy A. and Anthony Green (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70794-0.

- ↑ Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992). Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts. Styx. ISBN 90-72371-52-6.

Sources

- Frey-Anthes H. (2007). "Mischwesen". Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon (WiBiLex). Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in German)

- Hornung E. Komposite Gottheiten in der ägyptischen Ikonographie // Uehlinger C. (Hg.), Images as media. Sources for the cultural history of the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean (1st millennium BCE) (OBO 175), Freiburg (Schweiz) / Göttingen, 1–20. 2000. (in German)

- Nash H. Judgment of the humanness/animality of mythological hybrid (part-human, part-animal) figures // The Journal of Social Psychology. 1974. Т. 92. №. 1. pp. 91–102.

- Nash H. Human/Animal Body Imagery: Judgment of Mythological Hybrid (Part-Human, Part-Animal) Figures // The Journal of General Psychology. 1980. Т. 103. №. 1. pp. 49–108.

- Nash H. How Preschool Children View Mythological Hybrid Figures: A Study of Human/animal Body Imagery. University Press of America, 1982. 214 p. ISBN 0819123242, ISBN 9780819123244

- Nash H., Pieszko H. The multidimensional structure of mythological hybrid (part-human, part-animal) figures // The Journal of General Psychology. 1982. Т. 106. №. 1. pp. 35–55.

- Nash H. The Centaur’s Origin: A Psychological Perspective // The Classical World. 1984. pp. 273–291.

- Pires B. ANATOMY AND GRAFTS: From Ancient Myths, to Modern Reality / Pires M. A., Casal D., Arrobas da Silva F., Ritto I C., Furtado I A., Pais D., Goyri ONeill J E. / Nova Medical School, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portuguese Anatomical Society, (AAP/SAP), PORTUGAL.

- Posthumus L. Hybrid monsters in the Classical World: the nature and function of hybrid monsters in Greek mythology, literature and art. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Legendary creatures. |

- Religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch., Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (University of Zurich)