Matsya

| Matsya | |

|---|---|

|

Vishnu as Matsya | |

| Affiliation | Avatar of Vishnu |

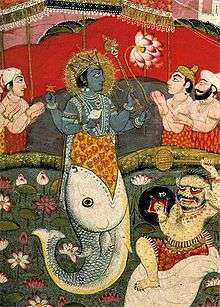

Matsya (Sanskrit: मत्स्य, lit. fish), is the fish avatar in the ten primary avatars of Hindu god Vishnu. Matsya is described to have rescued Manu and earthly existence from a great deluge.

The earliest accounts of Matsya as a fish-saviour equates him with the Vedic deity Prajapati. The fish-savior later merges with the identity of Brahma in post-Vedic era, and still later as an avatar of Vishnu.[1][2][3] The legends associated with Matsya expand, evolve and vary in Hindu texts. These legends have embedded symbolism, where a small fish with Manu's protection grows to become a big fish, and the fish saves earthly existence.[4][5]

Matsya iconography sometimes is zoomorphic as a giant fish with horn, or anthropomorphic in the form of a human torso connected to the rear half of a fish.[6][4]

Etymology

Matsya is a Sanskrit word and means "fish". The term appears in the Rigveda.[7] It is related to maccha, which also means fish.[7]

Textual history

Vedic

The section 1.8.1 of the Shatapatha Brahmana (Yajur veda) is the earliest extant text to mention Matsya and the flood myth in Hinduism. It makes no mention of Vishnu, instead identifies the fish with Prajapati-Brahma.[1][4][9] The central characters of this legend are the fish (Matsya) and Manu. The character Manu is presented as the legislator and the ancestor king. One day, water is brought to Manu for his ablutions. In the water is a tiny fish. The fish states it fears being swallowed by a larger fish and appeals to Manu to protect him.[4] In return, the fish promises to rescue Manu from an impending flood. Manu accepts the request. He puts the fish in a pot of water where he grows. Then he prepares a ditch filled with water, and transfers him there where it can grow freely. Once the fish grows further to be big enough to be free from danger, Manu transfers him into ocean.[4][10] The fish thanks him, tells him the date of the great flood, and asks Manu to build a boat by that day, one he can attach to its horn. On the predicted day, Manu visits the fish with his boat. The devastating floods come, Manu ties the boat to the horn. The fish carries the boat with Manu to the high grounds of the northern mountains (interpreted as Himalayas). Manu then re-establishes life by performing austerities and by performing yajna (sacrifices).[4]

According to Bonnefoy, the Vedic story is symbolic. The little fish alludes to the Indian "law of the fishes", an equivalent to the "law of the jungle".[4] The small and weak would be devoured by the big and strong, and needs the dharmic protection of the legislator and king Manu to enable it to attain its potential and help later. Manu provides the protection, the little fish grows to become big and ultimately saves all existence. The boat that Manu builds to get help from the savior fish, states Bonnefoy, is symbolism of the means to avert complete destruction and for human salvation. The mountains are symbolism for the doorway for ultimate refuge and liberation.[4]

Mahabharata

The tale of Matsya appears in chapter 12.187 of the Book 3, the Vana Parva, in the epic Mahabharata.[2][4][9] The legend begins with Manu performing religious rituals on the banks of the Cherivi River. A little fish called Matsyaka[7] comes to him and asks for his protection, promising to save him from a deluge in the future.[1] The legend moves in the same vein as the Vedic version. Manu places him in the jar. Once it outgrows it, the fish asks to be put into tank which Manu helps with. Then the fish outgrows the tank, and with Manu's help reaches the Ganges River, finally to the ocean. Manu is asked by the fish, in the Mahabharata version, to build a ship and be in it with Rishis (sages) and all sorts of grains, on the day of the expected deluge.[1][4] Manu accepts the fish's advice. The deluge begins, the fish arrives to Manu's aid. He ties the ship to the fish, who then steers the ship to the Himalayas, carrying Manu through a turbulent storm. The danger passes. The fish then reveals himself as Brahma, and gives the power of creation to Manu.[1]

The key difference between the Vedic version and the Mahabharata version of the allegorical legend is the latter's identification of Matsya with Brahma, more explicit discussion of the "law of the fishes" where the weak needs the protection from the strong, and the fish asking Manu to bring along sages and grains.[4][10][11]

Puranas

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Important deities |

|

Sampradayas |

|

|

According to George Williams, there are many versions of the Matsya mythology in the Puranas. The names of the characters, the details, the plot and the message diverge in this genre of texts.[12][13]

Matsya Purana

The Matsya Purana evolves the legend further, by identifying the fish-savior (Matsya) with Vishnu instead of Brahma.[14] The Purana derives its name from Matsya.

The legend as it appears in section 1.12 states that when a little fish appears to Manu,[note 1] he recognizes Vishnu Vasudeva in the fish. The fish tells him about the impending fiery end of kalpa accompanied with a deluge. The fish once again has a horn, but Manu does not need to build a boat or ship in this Purana. The gods build it. They build it big enough to carry and save all life forms, and Manu needs to just carry all types of grain seeds to produce food for everyone after the deluge is over. When the great flood begins, Manu ties the Ananta Sesha (cosmic serpent) to the fish's horn. The fish carries everyone to safety.[14][17] According to Bonnefoy, the Matsya Puranic story is also symbolic though quite different. The fish is divine to begin with, and needs no protection, only recognition and devotion. It also ties the story to its cosmology, connecting two kalpas through the cosmic symbolic residue in the form of Sesha.[14]

In another version of the Matsya Purana, the story is closer to the Mahabharata version. At the end of Kalpa, Brahma is resting and a demon Hayagriva steals the Vedas.[18] Vishnu discovers the theft. He descends to earth in the form of a little fish, or the Matsya avatar. One day, the king of Dravida desha (South India) named Satyavrata cups water in his hand to offer it to his ancestors. There he finds a little fish.[18] The fish asks him to save him from predators and let him grow. Satyavrata is filled with compassion for the little fish. He puts the fish in a pot, from there to a well, then a tank, and when it outgrows the tank, he transfers the fish finally to sea. The fish rapidly outgrows the sea.[18][13] Satyavrata realizes this is no ordinary fish, and asks the fish, "who are you?" The fish identifies itself as Vishnu, and informs the king of the impending deluge. The king is asked to save one member of every species of animal, plant and seeds in a boat and along with all this, a copy of the Vedas. The fish asks the king to tie the boat to its fins with the help of Sesha serpent. The deluge comes. The fish avatar saves existence. A new cycle of life restarts after the great deluge ends.[18][note 2]

Bhagavata Purana

The Bhagavata Purana presents a modified version for the Matsya mythology. The story is presented through a character named Badarayani.[2] At the end of a kalpa, as the world dissolved and was overwhelmed by a flooding ocean, the demon Hayagriva ("horse-faced" asura) steals the Vedas from sleepy Brahma.[14] Vishnu takes the avatar of saphari fish, dives down to locate the Vedas and the demon, recovers the Vedas from the ocean.[2]

In another version of the Bhagavata Purana text, the man-fish avatar of Vishnu not only recovers the Vedas from the demon Hayagriva who stole and tried to destroy it, but the avatar also saves the sage Satyavrata, the Saptarishis (seven sages), animals, seeds of all plant species. In this version of the legend, while swimming and carrying them all to safety, the fish avatar teaches the highest knowledge to the rishis and Satyavrata to prepare them for the next cycle of existence.[19]

Agni Purana

The Agni Purana version presents the legend through Agni (fire deity) describing the story to sage Vasishtha.[20] Agni describes how god Hari (Vishnu) saved the good from the evil through his fish avatar. As Brahma starts to sleep, an asura steals the Vedas. Meanwhile, Vaivasvata Manu was making his religious offering in Kritamala River, when a small fish appeared in his hand.[20] The fish asked Manu to protect him from larger fishes. Manu accepts the request, puts the fish in a jar. When the fish outgrows it, Manu puts it in a pond, then a lake, finally into the sea. Once there, the fish instantly expands to a gigantic size. Manu then realizes that the fish is Vishnu Narayana, and accepts he was deluded previously. The fish then informs the king that a flood is coming in seven days, to go collect all kinds of seeds and the seven sages, then board the boat that has been made for him.[20] Manu does so. The fish with horn appears. They tie the boat to the horn and the fish saves them. The fish then finds the asura Hayagriva, slays him, recovers the Vedas and gives it to seven sages and Manu.[20]

Vishnu avatar

Matsya is generally enlisted as the first avatar of Vishnu, especially in Dashavatara (ten major avatars of Vishnu) lists. However, that was not always the case. Some lists do not list Matsya as first, only later texts start the trend of Matsya as the first avatar.[17]

Iconography

Matsya is depicted in two forms: as a zoomorphic fish or in an anthropomorphic form. In the latter form, the upper half is that of the four-armed man and the lower half is a fish. The upper half resembles Vishnu and wears the traditional ornaments and the kirita-makuta (tall conical crown) as worn by Vishnu. He holds in two of his hands the Sudarshana chakra (discus) and a shankha (conch), the usual weapons of Vishnu. The other two hands make the gestures of varadamudra, which grants boons to the devotee, and abhayamudra, which reassures the devotee of protection.[21] In another configuration, he might have all four attributes of Vishnu, namely the Sudarshana chakra, a shankha, a gada (mace) and a lotus.[17]

In some representations, Matsya is shown with four hands like Vishnu, one holding the chakra, another the shankha, while the front two hands hold a sword and a book signifying the Vedas he recovered from the demon. Over his elbows is an angavastra draped, while a dhoti like draping covers his hips.[22]

In rare representations, his lower half is human while the upper body (or just the face) is of a fish. The fish-face version is found in a relief at the Chennakesava Temple, Somanathapura.[23]

Matsya may be depicted alone or in a scene depicting his combat with a demon. A demon called Shankhasura emerging from a conch is sometimes depicted attacking Matsya with a sword as Matsya combats or kills him. Both of them may be depicted in the ocean, while the god Brahma and/or manuscripts or four men, symbolizing the Vedas may be depicted in the background.[22]

Comparative mythology

The story of a great Deluge is found in many civilizations across the earth. It is often related to the Genesis narrative of the flood and Noah's Ark.[17] The fish motif reminds readers of the Biblical 'Jonah and the Whale' narrative as well; this fish narrative, as well as the saving of the scriptures from a demon, are specifically Hindu traditions of this style of the flood narrative.[18] Similar flood myths also exist in tales from ancient Sumer and Babylonia, Greece, the Maya of Americas and the Yoruba of Africa.[17]

Matsya is believed to symbolise the aquatic life as the first beings on earth.[24] Another symbolic interpretation of the Matsya mythology is, states Bonnefoy, to consider Manu's boat to represent moksha (salvation), which helps one to cross over. The Himalayas are treated as a boundary between the earthly existence and land of salvation beyond. The protection of the fish and its horn represent the sacrifices that help guide Manu to salvation. Treated as a parable, the tale advises a good king should protect the weak from the mighty, reversing the "law of fishes" and uphold dharma, like Manu, defines an ideal king.[4] In the tales where the demon hides the Vedas, dharma is threatened and Vishnu as the divine Saviour, rescues dharma, aided by his earthly counterpart, Manu - the king.[14]

Worship

There are very few temples dedicated to Matsya. Prominent ones include the Shankhodara temple in Bet Dwarka and Vedanarayana Temple in Nagalapuram.[24] The Koneswaram Matsyakeswaram temple in Trincomalee is now destroyed. Matsya Narayana Temple, Bangalore also exists.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Krishna 2009, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Rao pp. 124-125

- ↑ "Matsya". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bonnefoy 1993, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ George M. Williams 2008, pp. 212-213.

- ↑ Rao p. 127

- 1 2 3 Monier Monier-Williams, Sanskrit-English Dictionary and Etymology, Oxford University Press, pages 776-777

- ↑ A. L. Dallapiccola (2003). Hindu Myths. University of Texas Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-292-70233-2.

- 1 2 Surabhi Sheth (1979). Religion and Society in the Brahma Purana. Sterling. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8426-1102-2.

- 1 2 Alain Daniélou (1964). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 166–167 with footnote 1. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ↑ Alf Hiltebeitel (1991). The cult of Draupadī: Mythologies. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–178, 202-203 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-1000-6.

- ↑ George M. Williams 2008, p. 212.

- 1 2 3 Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 155–165. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bonnefoy 1993, p. 80.

- ↑ Ronald Inden; Jonathan Walters; Daud Ali (2000). Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-19-535243-6.

- ↑ Bibek Debroy; Dipavali Debroy (2005). The history of Puranas. Bharatiya Kala. p. 640. ISBN 978-81-8090-062-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roshen Dalal (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Krishna 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ George M. Williams 2008, p. 213.

- 1 2 3 4 Rao pp. 125-6

- ↑ Rao p. 127

- 1 2 British Museum; Anna Libera Dallapiccola (2010). South Indian Paintings: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd. pp. 78, 117, 125. ISBN 978-0-7141-2424-7. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Hindu Temple, Somnathpur

- 1 2 Krishna p. 36

Further reading

- Bonnefoy, Yves (15 May 1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- Krishna, Nanditha (2009). The Book of Vishnu. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306762-7.

- Rao, T.A. Gopinatha (1914). Elements of Hindu iconography. 1: Part I. Madras: Law Printing House.

- George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: a Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matsya. |