Mongol invasions and conquests

| Mongol invasions and conquests to success | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Expansion of the Mongol Empire 1206–94 | |||||||

| |||||||

Mongol invasions and conquests took place throughout the 13th century, resulting in the vast Mongol Empire, which by 1300 covered much of Asia and Eastern Europe. Historians regard the destruction under the Mongol Empire as results of some of the deadliest conflicts in human history. In addition, Mongol expeditions may have brought the bubonic plague along with them, spreading it across much of Asia and Europe and helping cause massive loss of life in the Black Death of the 14th century.[1][2][3][4]

The Mongol Empire developed in the course of the 13th century through a series of conquests and invasions throughout Asia, reaching Eastern Europe by the 1240s. In contrast with later empires such as the British, which can be defined as "empires of the sea", the Mongol empire was an empire of the land, a tellurocracy,[5] fueled by the grass-supported Mongol cavalry and cattle.[6] Thus most Mongol conquering and plundering took place during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grass for the herds.[6]

Tartar and Mongol raids against Russian states continued well beyond the start of the Mongol Empire's fragmentation around 1260. Elsewhere, the Mongols' territorial gains in China continued into the 14th century under the Yuan dynasty, while those in Persia persisted into the 15th century under the Timurid Empire. In India, a Mongol state survived into the 19th century in the form of the Mughal Empire.

Central Asia

.jpeg)

Genghis Khan forged the initial Mongol Empire in Central Asia, starting with the unification of the Mongol and Turkic confederations such as Merkits, Tartars, and Mongols. The Uighur Buddhist Qocho Kingdom surrendered and joined the empire. He then continued expansion of the empire via conquest of the Qara Khitai[7] and the Khwarazmian dynasty.

Large areas of Islamic Central Asia and northeastern Iran were seriously depopulated,[8] as every city or town that resisted the Mongols was subject to destruction. Each soldier was required to execute a certain number of persons, with the number varying according to circumstances. For example, after the conquest of Urgench, each Mongol warrior – in an army group that might have consisted of two tumens (units of 10,000) – was required to execute 24 people.[9]

Against the Alans and the Cumans (Kipchaks), the Mongols used divide and conquer tactics by first telling the Cumans to stop allying with the Alans and after the Cumans followed their suggestion the Mongols then attacked the Cumans[10] after defeating the Alans.[11] Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers. Mongols and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former Kingdom of Qocho and in Besh Balikh established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi (Ch'i Kung-chih).[12]

During the Mongol attack on the Mamluks in the Middle East, most of the Mamluk military was composed of Kipchaks, and the Golden Horde's supply of Kipchaks replenished the Mamluk armies and helped them fight off the Mongols.[13]

Hungary became a refuge after the Mongol invasions for fleeing Cumans.[14]

The de-centralized stateless Kipchaks only converted to Islam after the Mongol conquest, unlike the centralized Karakhanid entity made out of the Yaghma, Qarluqs, and Oghuz who converted to world religions.[15]

The Mongol conquest of the Kipchaks led to a merged society with the Mongol ruling class over a Kipchak speaking population which came to be known as Tatar and which eventually absorbed other ethnicities on the Crimean peninsula like Armenians, Italians, Greeks, and Goths to form the modern day Crimean Tatar people.[16]

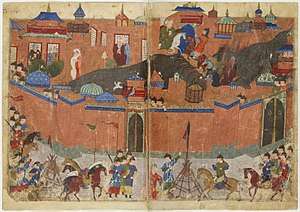

West Asia

The Mongols conquered, either by force or voluntary submission, the areas today known as Iran, Iraq, Caucasus and parts of Syria and Turkey, with further Mongol raids reaching southwards into the Palestine region as far as Gaza in 1260 and 1300. The major battles were the Siege of Baghdad (1258), when the Mongols sacked the city, which for 500 years had been the center of Islamic power, and the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, when the Muslim Kipchak Mamluks were able to defeat the Mongols in the battle at Ain Jalut in the southern part of the Galilee—the first time the Mongol advances had been decisively stopped. One thousand northern Chinese engineer squads accompanied the Mongol Khan Hulagu during his conquest of the Middle East.[17]

East Asia

.jpeg)

Genghis Khan and his descendants launched numerous invasions of China, subjugating the Western Xia in 1209 before destroying them in 1227, defeating the Jin dynasty in 1234 and defeating the Song dynasty in 1279. They made the Kingdom of Dali into a vassal state in 1253 after the Dali King Duan Xingzhi defected to the Mongols and helped them conquer the rest of Yunnan, forced Korea to capitulate through invasions, but failed in their attempts to invade Japan.

The Mongols' greatest triumph was when Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in China in 1271. The Yuan dynasty created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and an army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[18]

The Mongol force which invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.[19]

The Yuan dynasty established the top-level government agency Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs to govern Tibet, which was conquered by the Mongols and put under Yuan rule. The Mongols also invaded Sakhalin Island between 1264 and 1308. Likewise, Korea (Goryeo) became a semi-autonomous vassal state and compulsory ally of the Yuan dynasty for about 80 years. The Yuan dynasty was eventually overthrown during the Red Turban Rebellion in 1368 by the Han Chinese who gained independence and established the Ming dynasty.

Europe

The Mongols invaded and destroyed Volga Bulgaria and Kievan Rus', before invading Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria, and others. Over the course of three years (1237–1240), the Mongols destroyed and annihilated all of the major cities of Russia with the exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov.[20]

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, the Pope's envoy to the Mongol Great Khan, traveled through Kiev in February 1246 and wrote:

They [the Mongols] attacked Rus, where they made great havoc, destroying cities and fortresses and slaughtering men; and they laid siege to Kiev, the capital of Rus; after they had besieged the city for a long time, they took it and put the inhabitants to death. When we were journeying through that land we came across countless skulls and bones of dead men lying about on the ground. Kiev had been a very large and thickly populated town, but now it has been reduced almost to nothing, for there are at the present time scarce two hundred houses there and the inhabitants are kept in complete slavery.[21]

The Mongol invasions induced population displacement on a scale never seen before in central Asia as well as eastern Europe. Word that the Mongol hordes were approaching would spread terror and panic.[22]

South Asia

From 1221 to 1327, the Mongol Empire launched several invasions into the Indian subcontinent. The Mongols occupied parts of modern Pakistan and other parts of Punjab for decades. However, they failed to penetrate past the outskirts of Delhi and were repelled from the interior of India. Centuries later, the Mughal Empire, with Mongol roots from Central Asia, conquered the northern part of the sub-continent.

Southeast Asia

.jpg)

Kublai Khan's Yuan dynasty invaded Burma between 1277 and 1287, resulting in the capitulation and disintegration of the Pagan Kingdom. However, the invasion in 1301 was repulsed by the Burmese Myinsaing Kingdom. The Mongol invasions of Vietnam (then known as Đại Việt) and Java resulted in defeat for the Mongols, although much of Southeast Asia agreed to pay tribute in order to avoid further bloodshed.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Timeline

- 1205, 1207–1208, 1209–1210, 1225–1227 invasion of Western Xia

- 1207 conquest of Siberia

- 1211–1234 conquest of Jin dynasty

- 1216–1220 conquest of Central Asia and Eastern Persia

- 1220–1223, 1235–1330 invasions of Georgia and the Caucasus

- 1220–1224 invasion of the Cumans

- 1222–1327 Mongol invasions of India

- 1223–1236 invasion of Volga Bulgaria

- 1231–1259 invasion of Korea

- 1235–1279 conquest of Song dynasty

- 1222, 1236–1242 Mongol invasion of Europe

- 1236–1242 invasion of Rus

- 1238–1239 invasion of North Caucasus

- 1238–1240 invasion of Cumania and Alania

- 1241 invasion of Poland and Bohemia;

- 1241 invasion of Hungary

- 1241 invasion of Austria and Northeast Italy

- 1241–1242 invasion of Croatia

- 1242 invasion of Serbia and Bulgaria

- 1240–1241 invasion of Tibet

- 1241–1244 invasion of Anatolia

- 1244–1265 invasion of Dali Kingdom

- 1251–1259 invasion of Persia, Syria and Mesopotamia

- 1253–1256 invasion of Yunnan

- 1257, 1284, 1287 invasions of Vietnam

- 1258 invasion of Baghdad

- 1258–1260 invasion of Halych-Volhynia, Lithuania and Poland

- 1260 Battle of Ain Jalut

- 1260 Mongol raid against Syria

- 1264–1265 raid against Bulgaria and Thrace

- 1264–1308 invasion of Sakhalin Island

- 1271 raid against Syria

- 1274, 1281 invasions of Japan

- 1274 raid against Bulgaria

- 1275, 1277 raids against Lithuania

- 1277 battle of Abulustayn

- 1277 invasion of Myanmar

- 1281 invasion of Syria

- 1284–1285 invasion of Hungary

- 1285 raid against Bulgaria

- 1283 invasion of Khmer Empire

- 1287 invasion of Myanmar

- 1287–1288 invasion of Poland

- 1293 invasion of Java

- 1299 invasion of Syria

- 1300 Mongol invasion of Myanmar

- 1300 Mongol invasion of Syria

- 1303 Invasion of Syria

- 1307 Mongol invasion of Gilan

- 1312 Mongol invasion of Syria

- 1324, 1337 Tatar raids against Thrace

- 1337, 1340 Ruthenian-Tatar raids against Poland

See also

- Battle of the Kalka River

- Political divisions and vassals of the Mongol Empire

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- List of Tatar and Mongol raids against Russian states

- Mongol and Tatar states in Europe

- Mongol invasion of Europe

- Mongol military tactics and organization

- Tatar invasions

- Total war and the Mongol Empire

References

- ↑ Robert Tignor et al. Worlds Together, Worlds Apart A History of the World: From the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present (2nd ed. 2008) ch. 11 pp. 472–75 and map pp. 476–77

- ↑

Compare: Barras, Vincent; Greub, Gilbert (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism" (PDF). Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 498. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

In the Middle Ages, a famous although controversial example is offered by the siege of Caffa (now Feodossia in Ukraine/Crimea), a Genovese outpost on the Black Sea coast, by the Mongols. In 1346, the attacking army experienced an epidemic of bubonic plague. The Italian chronicler Gabriele de’ Mussi, in his Istoria de Morbo sive Mortalitate quae fuit Anno Domini 1348, describes quite plausibly how the plague was transmitted by the Mongols by throwing diseased cadavers with catapults into the besieged city, and how ships transporting Genovese soldiers, fleas and rats fleeing from there brought it to the Mediterranean ports. Given the highly complex epidemiology of plague, this interpretation of the Black Death (which might have killed > 25 million people in the following years throughout Europe) as stemming from a specific and localized origin of the Black Death remains controversial. Similarly, it remains doubtful whether the effect of throwing infected cadavers could have been the sole cause of the outburst of an epidemic in the besieged city.

- ↑ Andrew G. Robertson, and Laura J. Robertson. "From asps to allegations: biological warfare in history," Military medicine (1995) 160#8 pp. 369–73.

- ↑ Rakibul Hasan, "Biological Weapons: covert threats to Global Health Security." Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies (2014) 2#9 p. 38. online Archived 2014-12-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

Dugin, Alexander (2012). "1: Toward a Geopolitics of Russia's Future". Last War of the World-Island: The Geopolitics of Contemporary Russia. Translated by Bryant, John. London: Arktos (published 2015). p. 4. ISBN 9781910524374.

Historically, Russians did not immediately realize the significance of their location and only accepted the baton of tellurocracy after the Mongolian conquests of Ghengis Khan, whose empire was a model of tellurocracy.

- 1 2 |Invaders|The New Yorker "Of necessity, the Mongols did most of their conquering and plundering during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grass for their herds. [...] Fuelled by grass, the Mongol empire could be described as solar-powered; it was an empire of the land. Later empires, such as the British, moved by ship and were wind-powered, empires of the sea. The American empire, if it is an empire, runs on oil and is an empire of the air.

- ↑ Sinor, Denis. 1995. “Western Information on the Kitans and Some Related Questions”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 115 (2). American Oriental Society: 262–69. doi:10.2307/604669.

- ↑ World Timelines – Western Asia – AD 1250–1500 Later Islamic Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Central Asian world cities", University of Washington.

- ↑ Sinor, Denis. 1999. “The Mongols in the West”. Journal of Asian History 33 (1). Harrassowitz Verlag: 1–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41933117.

- ↑ Halperin, Charles J.. 2000. “The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 63 (2). Cambridge University Press: [ https://www.jstor.org/stable/1559539 p. 235].

- ↑ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ↑ Halperin, Charles J.. 2000. “The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 63 (2). Cambridge University Press: 229–45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1559539.

- ↑ Howorth, H. H.. 1870. “On the Westerly Drifting of Nomades, from the Fifth to the Nineteenth Century. Part III. The Comans and Petchenegs”. The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London (1869–1870) 2 (1). [Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Wiley]: 83–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3014440.

- ↑ Golden, Peter B.. 1998. “Religion Among the Q1pčaqs of Medieval Eurasia”. Central Asiatic Journal 42 (2). Harrassowitz Verlag: 180–237. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41928154.

- ↑ Williams, Brian Glyn. 2001. “The Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. An Historical Reinterpretation”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 11 (3). Cambridge University Press: 329–48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25188176.

- ↑ Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, ed. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Vol. II, L–Z, index. Routledge. p. 510. ISBN 0-415-96690-6. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

This called for the employment of engineers to engaged in mining operations, to build siege engines and artillery, and to concoct and use incendiary and explosive devices. For instance, Hulagu, who led Mongol forces into the Middle East during the second wave of the invasions in 1250, had with him a thousand squads of engineers, evidently of north Chinese (or perhaps Khitan) provenance.

- ↑ Hucker 1985, p. 66.

- ↑ Smith, Jr. 1998, p. 54.

- ↑ "BBC Russia Timeline". BBC News.

- ↑ The Destruction of Kiev Archived 2011-04-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Diana Lary (2012). Chinese Migrations: The Movement of People, Goods, and Ideas over Four Millennia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49.

- ↑ Taylor 2013, pp. 103, 120.

- ↑ ed. Hall 2008, p. 159.

- ↑ Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K.; Dutton, George (21 August 2012). "Sources of Vietnamese Tradition". Columbia University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Gunn 2011, p. 112.

- ↑ Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Lewis, Robin Jeanne (1 January 1988). "Encyclopedia of Asian history". Scribner – via Google Books.

- ↑ Woodside 1971, p. 8.

Further reading

- Boyle, J.A. The Mongol World Enterprise, 1206–1370 (London 1977)

- Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700

- May, Timothy. The Mongol Conquests in World History (London: Reaktion Books, 2011) online review; excerpt and text search

- Morgan, David. The Mongols (2nd ed. 2007)

- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests (2001) excerpt and text search

- Smith Jr., John Masson (Jan–Mar 1998). "Review: Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2307/606298. JSTOR 606298.

- Turnbull, Stephen. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Bayarsaikhan Dashdondog. The Mongols and the Armenians (1220–1335). BRILL (2010)

Primary sources

- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols and Global History: A Norton Documents Reader (2011)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mongol conquests. |