First Mongol invasion of Poland

| First Mongol invasion of Poland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasion of Europe | |||||||

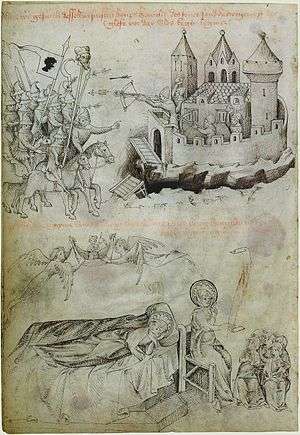

The Mongols at Legnica display the head of Duke Henry II of Silesia (a 15th-century illumination from the Legend of St. Hedwig) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Baidar Kadan Orda Khan |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 10,000 (one tumen)[lower-alpha 2] |

Disputed (see Battle of Legnica) | ||||||

The Mongol Invasion of Poland from late 1240 to 1241 culminated in the battle of Legnica, where the Mongols defeated an alliance which included forces from fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry II the Pious, the Duke of Silesia. The first invasion's intention was to secure the flank of the main Mongolian army attacking the Kingdom of Hungary. The Mongols neutralized any potential help to King Béla IV being provided by the Poles or any military orders.

Background

The Mongols invaded Europe with three armies. One of the three armies was tasked with distracting Poland, before joining the main Mongol force invading Hungary. The Mongol general in charge, Subutai, did not want the Polish forces to be able to threaten his flank during the primary invasion of Hungary. Thus, the Mongol goal was to use a small detachment to prevent the Poles from assisting Hungary until the Hungarians were defeated. That army, under Baidar, Kadan and Orda Khan, began scouting operations in late 1240.[1] Though the Mongols may have entered with relatively modest goals and forces, they almost completely annihilated all Polish forces and influenced the Bohemian army to defend its homeland instead of assisting the beleaguered Hungary.

Invasion

A key feature of the invasion was the speed and uncertainty of the Mongol advances. Though the full Polish forces were far larger than the meager two Mongol tumens (12-20,000 men)[2] assigned to defeat them, the Mongols attacked from multiple axes before the Polish armies could merge into one united force. As a result, the Mongols defeated multiple piecemeal Polish armies in various battles and skirmishes who lacked the time to properly organize.

Mongol tumen, moving from recently conquered Volodymyr-Volynskyi in Kievan Rus, first sacked Lublin,[3] then besieged and sacked Sandomierz (which fell on 13 February).[3] Around this time, their forces split.[3] Orda's forces devastated central Poland, moving to Wolbórz and as far north as Łęczyca, before turning south and heading via Sieradz towards Wrocław.[3] Baidar and Kadan ravaged the southern part of Poland, moving to Chmielnik, Kraków, Opole and finally, Legnica, before leaving Polish lands heading west and south.[3]

Baidar and Kadan on 13 February defeated a Polish army under the voivode of Kraków, Włodzimierz, in the battle of Tursko.[4] On 18 March they defeated another Polish army with units from Kraków and Sandomierz at the battle of Chmielnik.[4] Panic spread through the Polish lands, and the citizens abandoned Kraków, which was seized and burned by the Mongols by 24 March.[4] In the meantime, one of the most powerful contemporary Dukes of Poland, and Duke of Silesia, Henry II the Pious, gathered his forces and allies around Legnica (German: Liegnitz).[4] Henry, in order to gather more forces, even sacrificed one of the largest towns of Silesia, Wrocław (Breslau), abandoning it to the Mongols.[4] Henry was also waiting for Wenceslaus I of Bohemia, his brother-in-law, who was coming to his aid with a large army.[4]

While considering whether to besiege Wrocław, Baidar and Kadan received reports that the Bohemians were days away with a large army.[4] The Mongols turned from Wrocław, not finishing the siege, in order to intercept Henry's forces before the European armies could meet.[4] The Mongols caught up with Henry near Legnica at place known later as Wahlstatt ("Battlefield" in Middle High German;[5] now village Legnickie Pole, "Field of Legnica"). Henry, in addition to his own forces, was aided by Mieszko II the Fat (Mieszko II Otyły), as well as remnants of Polish armies defeated at Tursk and Chmielnik, members of military orders and small numbers of foreign volunteers.[4]

The decisive battle for Poland occurred at battle of Legnica on 9 April. A European knight charge appeared to cause that section of the Mongol line to rout, thus leading Henry II to commit his cavalry to chase them. However, the Mongols merely had lured the knights away from their supporting infantry, and used a smokescreen to prevent the infantry and remaining cavalry from seeing their more advanced knights being surrounded and massacred. Once the Polish/German knights were killed, the remainder of the Polish army was vulnerable and easily encircled. The later Polish chronicler Jan Długosz claimed that the Mongols caused confusion in the Polish forces by yelling 'Flee!' in Polish through the smokescreen. The Mongols did not take Legnica castle, but had a free rein to pillage and plunder Silesia, before moving off to join their main forces in Hungary.[6]

Legend

A contingent of Teutonic Knights of indeterminate number is traditionally believed to have joined the allied army. However, recent analysis of the 15th-century Annals of Jan Długosz by Labuda suggests that the German crusaders may have been added to the text after chronicler Długosz had completed the work. A legend that the Prussian Landmeister of the Teutonic Knights, Poppo von Osterna, was killed during the battle is false, as he died at Legnica years later while visiting his wife's nunnery.[7] The Hospitallers have also been said to have participated in this battle, but this too seems to be a fabrication added in later accounts; neither Jan Długosz's accounts nor the letter sent to the King of France (then Saint Louis) from the Templar Grand Master Ponce d'Aubon mention them.[8] Peter Jackson further points out that the only military order that fought at Legnica was the Templars.[9] The Templar contribution was very small, estimated around 68–88 well-trained, well-armed soldiers;[10] their letter to the king of France gives their losses as nine brother knights, three sergeants and 500 'men'—according to their use of the term, probably peasants working their estates and thus neither better armed or trained than the rest of the army's infantry.

Aftermath

The Mongols avoided the Bohemian forces, who were too frightened to advance forward and assist the Hungarians, and defeated the Hungarians in the Battle of Mohi.[6] But news that the Grand Khan Ögedei had died the previous year along with disagreements between the Mongol princes Batu, Guyuk, and Buri caused the descendants of the Grand Khan to return to the Mongol capital of Karakorum for the kurultai which would elect the next Khagan, and probably saved the Polish lands from being completely overrun by the Mongols.[6]

The death of Duke Henry, who was close to unifying the Polish lands and reversing their fragmentation, set back the unification of Poland, and also meant the loss of Silesia, which would drift outside the Polish sphere of influence (and gradually became a part of the Bohemian Crown) until the unification took place in the 14th century.[11]

Later Mongol invasions

There were also later, larger Mongol invasions of Poland (1259–1260 and 1287–1288).[12]

In 1254 or 1255, Daniel of Galicia revolted against the Mongol rule. He repelled the initial Mongol assault under Orda's son Quremsa. In 1259, the Mongols returned under the new command of Burundai (Mongolian: Borolday). According to some sources, Daniel fled to Poland leaving his son and brother at the mercy of the Mongol army. He may have hidden in the castle of Galicia instead. The Mongols needed to secure Poland's aid to Daniel and war booty to feed the demand of their soldiers. Lithuanians also attacked Smolensk and menaced Torzhok, tributaries of the Golden Horde, in c. 1258.[13] The Mongols sent a punitive expedition into Lithuania for this. The Lithuanians appear to have not resisted them efficiently. Borolday again demanded Daniel to recruit more troops. After demolishing walls of all towns in Galicia and Volhyinia, in 1259, 18 years after the first attack to Poland, two tumens (20,000 men) from the Golden Horde, under the leadership of Berke, attacked Poland after raiding Lithuania. This attack was commanded by the young prince Nogai Khan and general Burundai. The Rus' soldiers under Daniel's son, Lev, and brother, Vasily, joined the Mongol expedition. Lublin, Sandomierz, Zawichost, and Kraków were ravaged and plundered by the Mongol army. Berke had no intention of occupying or conquering Poland. After this raid Pope Alexander IV tried without success to organize a crusade against the Tatars.

North-western Rus princes complained of the repeated attacks of the Kingdom of Poland to their Mongol masters. Nogai's army recruited troops from Rus principalities and it included Vlakh, Kipchak, and Alan soldiers. An unsuccessful raid followed in 1287, led by Talabuga and Nogai Khan. Lublin, Masovia, Sandomierz and Sieradz were successfully raided, but they were defeated at Kraków. Despite this, Kraków was devastated. This raid consisted of less than one tumen, since the Golden Horde's armies were tied down in a new conflict which the Il-Khanate had initiated in 1284. The force retreated instead of facing the larger Polish force.

Ozbek Khan and Jani Beg warred with the powerful kingdom of Poland to secure their claim on western Rus (modern Belarus and Ukraine).[14] Towards 1356, Casimir III the Great reached an agreement with the Golden Horde and apparently undertook to pay tribute in exchange for military support against Lithuania. In a letter to the Teutonic master, he claimed that seven Mongol princes commanding troops were coming to his aid. The Knights, however, were seeking a rapprochement with Lithuania and accused Casimir to the popes as having submitted to the Mongols.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Some Polish medieval chronicles call this exiled member of Děpolt family (a cadet branch of the Přemyslid dynasty) as "Margrave of Moravia" but this title had no merit because Bohemia and Moravia were ruled at that time jointly by one king, Wenceslaus I of Bohemia; moreover, Boleslaus styled himself as Dux Boemiae ("Duke of Bohemia")

- ↑ Sources vary, with estimates of Mongol forces from 10,000 to 50,000.

References

- ↑ Bitwa.., p. 8

- ↑ Timothy May, the Mongol Art of War (2016).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bitwa.., map on p. 4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bitwa.., p. 9

- ↑ Boková, Hildegard; Spáčilová, Libuše (2003). "wahlstatt". Kurzes frühneuhochdeutsches Glossar zu Quellen aus den Böhmischen Ländern = Stručný raně novohornoněmecký glosář k pramenům z českých zemí (in German and Czech). Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého. p. 502. ISBN 80-244-0737-X.

- 1 2 3 Bitwa.., p. 12

- ↑ William Urban. The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. Greenhill Books. London. 2003. ISBN 1-85367-535-0

- ↑ Burzyński, p.22

- ↑ Jackson, p. 205

- ↑ Burzyński, p. 24

- ↑ Bitwa.., p. 13

- ↑ (in Polish) Jacek Kawecki, Najazd mongolski na Polskę w 1287 roku

- ↑ Новгородская летопись

- ↑ Michael B.Zdan – The Dependence of Halych-Volyn' Rus' on the Golden Horde, pp.516

- ↑ Peter Jackson-the Mongols and the West, p.211

Sources

- Jaworski, Rafał (12 August 2006). "Bitwa pod Legnicą, Chwała Oręża Polskiego". Mówią Wieki (in Polish) (Nr 3).

- Urban, William (2003). The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. Greenhill Books.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West. Routledge.

- Zdan, Michael (1957). "The Dependence of Halych-Volyn Rus' on the Golden Horde". Slavonic and East European Review. 35:85 June.

Further reading

- Gerard Labuda, Wojna z tatarami w roku 1241, Prz. Hist. — T. 50 (1959), z. 2, pp. 189–224

- Wacław Zatorski, Pierwszy najazd Mongołów na Polskę w roku 1240–1241, Prz. Hist.-Wojsk. — T. 9 (1937), pp. 175–237