Medri Bahri

| Medri Bahri ('Land of the Sea') Medri Bahri ምድሪ ባሕሪ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15th century–1879 | |||||||

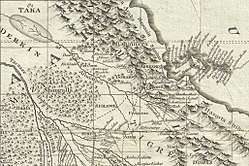

Eritrea and Tigray on a map by James Bruce, 1770. | |||||||

| Capital |

Debarwa (Until 17th century) Tsazega (17th century-1879) | ||||||

| Common languages | Tigrinya · Geez | ||||||

| Religion | Coptic Christianity | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Bahri Negash | |||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• First mentioned | 15th century | ||||||

• Coastline conquered by the Ottomans | 1557 | ||||||

| 1879 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||

Medri Bahri (Tigrinya: ምድሪ ባሕሪ) was a medieval semi-unified political entity in the Horn of Africa. Also known as Marab(Merab) Melash[1] was situated in modern-day Eritrea, it was ruled at times by the Bahri Negus (also called the Bahri Negasi or Bahr Negash) and lasted from the 15th century to the Ethiopian occupation in 1879. It survived several threats like the invasion of Imam Gran and the Ottoman Red Sea expansion, albeit Medri Bahri irretrievably lost its access to the Red Sea due to the latter. The relation to the Ethiopian empire in the south varied from time to time, ranging from virtual autonomy to tributary status to de facto annexation. At first the residence of the Bahr Negash was at Debarwa, but during the 17th century it was relocated to the village of Tsazega due to the same-named clan taking control of the kingdom.

History

Origins and turbulent 16th century

After the Aksumite empire, the area from the Eritrean highlands to the Red Sea was known as Ma'ikele Bahr ("between the seas/rivers," i.e. the land between the Red Sea and the Mereb river).[2] It was later renamed as the domain of the Bahr Negash ("Ruler of the sea"), the Medri Bahri ("Land of the Sea", "Sea land" in Tigrinya, although it included some areas like Shire on the other side of the Mereb, today in Ethiopia).[3] The first time the title Bahr Negash appears is during the reign of emperor Zara Yaqob (r. 1433-1468), who perhaps even introduced that office.[4] His chronicle explains how he put much effort into increasing the power of that office, placing the Bahr Negash above other local chiefs and eventually making him the sovereign of a territory covering the Shire, a region south of the Mareb river in what is now Ethiopia, Hamasien and Bur, which stretched from the north-eastern highlands to the Gulf of Zula.[4][5] To strengthen the imperial presence in Medri Bahri, Zara Yaqob also established a military colony consisting of Maya warriors from the south of his realm.[4]

In the 1520s, Medri Bahri was described by the Portuguese traveller and priest Francisco Alvares. The current Bahr Negash bore the name Dori and resided in Debarwa, a town on the very northern edge of the highlands. Dori was an uncle of emperor Lebna Dengel, to whom he paid tribute.[6] These tributes were traditionally paid with horses and imported cloth and carpets.[7] Dori was said to wield considerable power and influence, with his kingdom reaching almost as far north as Suakin, plus he was also a promoter of Christianity, gifting the churches everything they needed.[8] By the time of Alvares' visit, Dori was enganged in warfare against some Nubians after the latter had killed his son. The Nubians were known as robbers and generally had a rather bad reputation.[9] They originated somewhere five to six days away from Medri Bahri, possibly Taka (A historical province named after Jebel Taka near modern Kassala).[10]

The Bahre-Nagassi ("Kings of the Sea") alternately fought with or against the Abyssinians and the neighbouring Muslim Adal Sultanate depending on the geopolitical circumstances. Medri Bahri was thus part of the Christian resistance against Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi of Adal's forces, but later joined the Adalite states and the Ottoman Empire front against Abyssinia in 1572. During the 16th century said Ottomans also began making inroads in the Red Sea area.[11] The territory became an Ottoman province or eyalet known as the Habesh Eyalet. Massawa served as the new province's first capital. When the city became of secondary economic importance, the administrative capital was soon moved across the Red Sea to Jeddah. Its headquarters remained there from the end of the 16th century to the early 19th century, with Medina temporarily serving as the capital in the 18th century.[12] Turks briefly occupied the highland parts of Baharnagash in 1559 and withdrew after they encountered resistance and pushed back by the Bahrnegash and highland forces. In 1578 they tried to expand into the highlands with the help of Bahr negus Yeshaq who has switched alliances due to power struggle, and by 1589 once again they were apparently compelled to withdraw their forces to the coast. After that Ottomans abandoned their ambitions to establish themselves on the highlands and remained in the lowlands until they left the region by 1872.[13]

After the death of Yeshaq, emperor Sarsa Dengel elected a new Bahr Negash and temporarily merged that office with the governorate of Tigray. In 1587, the Ottomans attacked the highlands yet again, conquered Debarwa and routed the current governour / Bahr Negash, Dejazmach Daherno. Thereafter they tried to cross the Mareb, but while doing so they got ambushed by a local chief named Aquba Michael, whom Sarsa Dengel then awarded with the office of Bahr Negash. The imperial army eventually reconquered Debarwa and killed the current Turkish Pasha, while Aquba Michael killed Wäd Ezum, who had been appointed as Bahr Negash by the Ottomans. Afterwards, the Ottomans abandoned their ambitions to conquer the highlands for good.[14]

17th century-1890

The Scottish traveler James Bruce reported in 1770 that Medri Bahri was a distinct political entity from Abyssinia, noting that the two territories were frequently in conflict.

The kingdom was eventually occupied in 1879, when Ras Alula seized control of the region and imprisoned Woldemichael Solomon, the last Bahr Negash. Alula, as governour of Mareb Mellash under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Empire, organized the resistance against the steadily enroaching Italians and eventually even defeated them at Dogali in 1887. Woldemichael Solomon was sent to the Amba Salama prison with his son Masfen and his son-in-law Kaffal Goffar. However, Kaffal, the son-in-law of Woldemichael Solomon continued the rebellion against the Ethiopian Empire by siding with the Italians in 1885. In 1888, Woldemichael Solomon had tried to urge his son-in-law to bring the Italians up to the highlands. By 1889 Alula was, however, forced to retreat to Tigray and the region that once constituted the kingdom of Medri Bahri fell to the Italians, who proclaimed it as a part of Italian Eritrea in 1890.[15][16]

Geography

Medri Bahri was in the highlands of Eritrea. The districts of Akele Guzay, Hamasien, and Seraye were the main districts/provinces of the kingdom. In the language of Tigrinya language "Medri Bahri" means "Land of the Sea" in reference to the Red Sea which Eritrea has a long coastline of this sea. This kingdom had a border to the south with Tigray Region, a province of the Ethiopian Empire also known as Abyssinia.

Demographics

Medri Bahri was composed of the following modern ethnic groups: Tigrayan people, Saho people, Tigre people.[17]

Notable people of Medri Bahri

- Bahr negus Yeshaq

- Woldemichael Solomon

- Bahta Hagos

- Ras Alula

- Balambras Kaffal Goffar

Notes

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=ZJLCZT7MW08C&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=ras+alula+yohannes&source=bl&ots=MawznerRFd&sig=nZaLspjh4ra7syaAuIOAozbNQlw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiU2eSyk7DZAhVC1WMKHQjeArg4ChDoAQhKMAo#v=onepage&q=melash&f=false

- ↑ Tamrat 1972, p. 74.

- ↑ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941–2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. United States of America: Signature Book Printing, Inc., 2005, pp.17-8.

- 1 2 3 Pankhurst 1997, p. 101.

- ↑ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Pankhurst 1997, p. 102-104.

- ↑ Pankhurst 1997, p. 270.

- ↑ Pankhurst 1997, p. 102-103.

- ↑ Pankhurst 1997, p. 154-155.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 149-150 & note 14. P. L. Shinnie suggests an origination from the area around Old Dongola, but could this region not be reached from Eritrea within five - six days of travelling time.

- ↑ Okbazghi Yohannes (1991). A Pawn in World Politics: Eritrea. University of Florida Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0-8130-1044-6. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Siegbert Uhlig (2005). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 951. ISBN 978-3-447-05238-2. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Jonathan Miran Red Sea Citizens: Cosmopolitan Society and Cultural Change in Massawa. Indiana University Press, 2009, pp. 38-39 & 91 Google Books

- ↑ Pankhurst 1997, p. 238-239.

- ↑ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 66-67.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=ZJLCZT7MW08C&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=ras+alula+yohannes&source=bl&ots=MawznerRFd&sig=nZaLspjh4ra7syaAuIOAozbNQlw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiU2eSyk7DZAhVC1WMKHQjeArg4ChDoAQhKMAo#v=onepage&q=1879&f=false%7C p.143-149 Between the Jaws of Hyenas

- ↑ Tronvoll 1998, p. 38.

References

- Connel, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century.

- Tamrat, Tadsesse (1972). Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527).

- Tronvoll, Kjetil (1998). Mai Weini, a Highland Village in Eritrea: A Study of the People. Red Sea Press.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche.