Mahra Sultanate

| Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra سلطنة المهرة في قشن وسقطرة | |||||

| State of the Protectorate of South Arabia | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Qishn (Mahra); Tamrida/Hadibu (Socotra) | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | 1886 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 30 November 1967 | |||

| Today part of | |||||

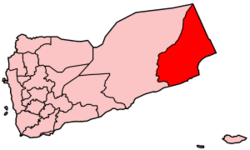

The Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra (Arabic: سلطنة المهرة في قشن وسقطرة Salṭanat al-Mahrah fī Qishn wa-Suquṭrah) or sometimes the Mahra Sultanate of Ghayda and Socotra (Arabic: سلطنة المهرة في الغيضة وسقطرى Salṭanat al-Mahrah fī al-Ghayḍā’ wa-Suquṭrah) was a sultanate that included the historical region of Mahra and the Indian Ocean island of Socotra in what is now eastern Yemen. It was ruled by the Banu Afrar (Arabic: بنو عفرار Banū ‘Afrār, also known as بن عفرير) dynasty and is sometimes called Mahra State in English.

In 1886, the Sultanate became a British protectorate and later joined the Aden Protectorate. The Sultanate was abolished in 1967 upon the founding of the People's Republic of South Yemen and is now part of the Republic of Yemen.[1]

The people of the Sultanate were essentially the Mehri people or speakers of the Mehri language, a modern South Arabian language. The Mehri share, with their regional neighbours on the island of Socotra and in Dhofar in Oman, cultural traditions like a modern South Arabian language, Arabic incursions, and frankincense agriculture. The region benefits from a coastal climate, distinct from the surrounding desert climate, with seasons dominated by the khareef or monsoon.

In 1967, with the departure of the British from the larger southern Arabian region, the Aden-based South Yemeni government divided the region formerly known as the thousand-year-old Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra, creating an Al Mahra Governorate, but moving Socotra to the Aden Governorate. In 2004, the Yemeni government moved Socotra to the Hadhramaut Governorate.[2]

History

The history of the Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra and its people is well documented and mainly written by non-Mahri historians who proved that the Al-Mahri people played a major role in the politics and the military of the Arab and Muslim world during the beginning of Islam. The Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra was established in the 10th century and lasted until 1967[3] when it was annexed by Soviet-supported South Yemen. At the height of its power, the Al-Mahra territory extended beyond its current borders in Al-Mahra and Socotra, and it has been documented that the Al-Mahri territory extended east into Oman and west into Ash Shihr near Mukalla.[4]

The history of the Mahra tribe began with the formation of the ʿĀd kingdom by an ancient Arab tribe called ʿĀd who settled in south Arabia in the modern-day Yemen-Oman border regions where modern-day Al-Mahra is located. The kingdom was a well-known nation which had connections with ancient Greece and Egypt. The exact location of the kingdom was depicted by Claudius Ptolemy in his book Geography.

Ibn al-Mujawir stated in his work that the Al-Mahri people are the only descendants of the ʿĀd Kingdom and blood relatives of Thamud who later founded the Thamud kingdom.[5] King ʿĀd was the great-grandson of Shem, son of Noah. According to the Quran the Thamud civilisation was descended from their forefather ʿĀd, and they migrated from south Arabia towards north Arabia. The Thamud civilisation was famed for their engineering abilities as they used to carve entire buildings out of mountains. Some Thamud-made buildings can still be seen in Mada'in Saleh in modern-day Saudi Arabia. The Prophet Saleh who had been sent to preach to the people, and the Prophet Hud originated from the land known today as Mahra, and both men shared ʿĀd as a common ancestor. Saleh and Hud and the Prophet Muhammad are the only Quranic prophets of Arab origin.

The forefather of the Mehri people was a man named Mahra bin Haydan bin Qahtan bin Yarub.[6] According to Islamic genealogies, Ya’rub was the grandson of the Prophet Hud (biblical Eber) and the forefather of the Himyarite Kingdom in Yemen who were the rulers of the Qataban and the Sabaeans kingdoms.[7][8] According to the Biblical sources, Eber (Prophet Hud) was the ancestor of the Israelites, and was the great-grandson of Shem.

Another man called Yarub who was Mahra’s son, was a talented man who was credited with the invention of the Arabic language, Kufic an Arabic script, and the origins of Arabic poetry.[9][10][11][12] Qahtan is the forefather of most of the tribes in southern Arabia which are called collectively Qahtanite and, according to Arabic genealogy, they are pure Arabs, whereas the Adnanites (descended from Adnan) are Arabized Arabs who took on the Arab identity of the Qahtanite.[13] The Qahtanites are divided into two sub-groups called the Himyar and the Kahlan,[14] and the Mehri are part of the Himyar sub-group of Qahtan, which makes them blood relatives of the kings of Qataban, Himyar, and Saba.

During ancient times, the ʿĀd Kingdom was a well-known transshipment point for the frankincense trade. It was exported mostly to ancient Europe. It has been suggested the ʿĀd Kingdom, and the current location of Mahra Sultanate, were the first places in the world where the camel was domesticated.[15]

The ʿĀd Kingdom had several kings starting with the legendary 'Ad ibn Kin'ad who was the founder of the kingdom. His successors included the legendary King Shaddad who, according to Islamic belief, defied the warnings of the Prophet Hud. King Shaddad built the pillared city of Iram or (Iram of the Pillars). He and his brother Shadidi were also mentioned in the 227th to 229th nights of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. In the book he is presented as a brutal and highly competent King who ruled all of Arabia and Iraq. According to Arabic-legends, Luqman was a wise man who was Shaddad's brother, but in Islamic teachings he was presented as an Abyssinian man who had no relation to the people of ʿĀd. In the English version of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, in the third volume, the story of King Shaddad is in the chapter titled "The City of Irem".

The non-Islamic historical account states that the ʿĀd kingdom was completely wiped out by natural disaster sometime between the 3rd and 6th century AD. However, the Quran mentions that the ʿĀd kingdom was annihilated by a sand storm as a result of disobeying God’s command. The ʿĀd kingdom and the Thamud, who were the Mehri tribe’s ancestors, are mentioned extensively in the Quran, and the Muslim people are often reminded in the Quran that those who disobey God will end up as the ʿĀd kingdom and the Thamud. The most well-known Passage from the Quran on ʿĀd kingdom is the 89th chapter (sura) of the Quran, verses 6 -14;

- 6. “Have you not seen how your Lord dealt with the 'Ad (people),"

- 7. "Of the (city of) Iram with lofty pillars,"

- 8. "The like of which were not created among (other) cities?"

- 9. "And the Thamood (people) who hewed out the (huge) rocks in the valley"

- 10. "And Pharaoh- of the many stakes"

- 11. "Who (all) transgressed in the land,"

- 12. "And made much corruption therein "

- 13. "Therefore did your Lord pour on them a scourge of diverse chastisement:"

- 14. "Surely your Lord is ever watchful.”

The 11th Chapter of the Quran was named after the Prophet Hud. In this chapter, Hud is mentioned as a man who is related to ʿĀd kings, and his relation with the ʿĀd people is mentioned again in the Quran in chapter 7. According to Islamic genealogy, Hud is also related to the Al-Mahri tribe through his grandson Yarub, the great-grandfather of Mahra, who is the progenitor of the Al-Mahri tribe (19). Verses 50-60 of chapter 11 give a detailed description of Prophet Hud and the 'Ad people and their wrongdoing as follows:

- 50. "And to ‘Ad (We sent) their brother Hud. He said: O my people, serve Allah, you have no god save Him. You are only fabricators."

- 51. "O my people, I ask of you no reward for it. My reward is only with Him Who created me. Do you not then understand?"

- 52 "And, O my people, ask forgiveness of your Lord, then turn to Him, He will send on you clouds pouring down abundance of rain and add strength to your strength, and turn not back, guilty."

- 53. "They said: O Hud, thou hast brought us no clear argument, and we are not going to desert our gods for thy word, and we are not believers in thee."

- 54. "We say naught but that some of our gods have smitten thee with evil. He said: Surely I call Allah to witness, and do you, too, bear witness that I am innocent of what you associate (with Allah)"

- 55. "Besides Him. So scheme against me all together, then give me no respite."

- 56. "Surely I put my trust in Allah, my Lord and your Lord. There is no living creature but He grasps it by its forelock. Surely my Lord is on the right path."

- 57. "But if you turn away, then indeed I have delivered to you that with which I am sent to you. And my Lord will bring another people in your place, and you cannot do Him any harm. Surely my Lord is the Preserver of all things."

- 58. "And when Our commandment came to pass, We delivered Hud and those who believed with him with mercy from Us; and We delivered them from a hard chastisement."

- 59. "And such were ‘Ad. They denied the messages of their Lord, and disobeyed His messengers and followed the bidding of every insolent opposer (of truth)."

- 60. "And they were overtaken by a curse in this world and on the day of Resurrection. Now surely ‘Ad disbelieved in their Lord. Now surely, away with ‘Ad, the people of Hud!"

The 7th chapter of the Quran, 73-78 indirectly mentions that the Thamud people are the remnants of the previously doomed ‘Ad people, and they were told by the Prophet Salah not to follow the ‘Ad’s example. The Thamud people refused to heed the warning and they were annihilated by an earthquake.

And again in Chapter 7 ("Al-'A`raf"), verse 65;

- 65. "And to the 'Aad [We sent] their brother Hud. He said, "O my people, worship Allah ; you have no deity other than Him. Then will you not fear Him?"

The ruins of the capital city of the ʿĀd Kingdom are buried somewhere under the Rub' al Khali (the Empty Quarter) a portion of which is home to the Al-Mahri nomadic community. However, satellite photography taken by NASA during the 1990s identified the site of a ruin in an area mainly inhabited by the Al-Mahri. Subsequent excavation of the area led to the uncovering of a large walled fort. The building was named Atlantis of the Sands, and many newspaper articles about it appeared across the world.[16]

Pre-Islamic al-Mahra

During the pre-Islamic period, the Mehri tribe of Oman and eastern Yemen were pagans like the rest of Arabia, and believed in the worship of more than one god. Before the time of Islam, the Arab people believed in the worship of tribal gods, legendary individuals, spirits (jinn), or natural phenomenon.

The Mehri tribe believed in various gods who each had a responsibility for one area of life like wealth, safety, or the afterlife. In Al-Mahri polytheism there were several important gods who were unique to their land, and some other gods were shared with the rest of pre-Islamic Arabia.

Embracing Islam

During the first decade of the Islamic calendar, a large delegation from Al-Mahra under the leadership of Mehri bin Abyad went to Medina to meet the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and during that meeting the entire Mehri tribe decided to embrace Islam. Before embracing Islam the tribe were polytheist and worshiped multiple deities. After the meeting in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad issued an injunction, stating that Mehri tribe are true Muslims and no war should be waged against them, and that any violator of the injunction shall be considered to be waging war against Allah.[17]

The entire Mehri tribe became some of the earliest adopters of Islam. Their action had an added bonus as becoming Muslims secured them a political alliance and stable relations with the Muslim leadership in Medina. Prior to embracing Islam, Al-Mahra was a vassal state of the Persian Empire and had been subjected to Persian control for many years. Siding with Medina enabled the Mehri people to break away from Persian control and regain their liberty.

Ridda wars (the wars of apostasy)

When Prophet Muhammad died in the year 632 AD many Arab tribes, including the Mehri tribe, interpreted the death as the end of Islam, and they abandoned the religion by either reverting to paganism or following certain individuals who claimed prophethood.[18] In year 634 the Mehri and other tribes rebelled against Caliph Abu Bakar who became the new leader of the Muslims, and he launched a new military campaign against the rebels.

There were not many records about the power structure within the Mehris, however, during the Ridda wars information regarding the intra-tribal affair was revealed by al-Tabari. According to al-Tabari,[18] before the death of Prophet Muhammad, there was an intra-tribal rivalry within the Mehri tribe, which consisted of two competing factions called the Bani Shakhrah faction and their bigger rival called the Bani Muharib. The Bani Muharib, who hailed from Al-Mahra’s mountain regions, always had the upper hand against their smaller rival.

A Muslim army under the command of Ikrimah ibn Abi Jahl was sent to Al-Mahra to face the Mehri who had turned their back on Islam like many Arab tribes. The Muslim army was too weak to confront the Mehri tribe in battle, and this situation forced Ikrimah to engage in political activity rather than initiating war in Al-Mahra. Ikrimah met with the leadership of the Bani Muharib faction and convinced them to return to Islam. After this event, the army under Ikrimah's command, and the Bani Muharib faction, formed a military alliance against the Bani Shakhrah. The Ridda War in Al-Mahra ended quickly as the newly formed alliance subdued the Bani Shakhrah faction without bloodshed. Islam was once again the only religion in Al-Mahra.

People

The Al Mahra have an estimated population of 700,000 living in Al Mahra alone and additional 300,000 living in the Arabian Peninsula, mostly in the adjacent regions in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, Dhofar region in Oman, and further afield in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. There is no reliable statistical data on the Mehri, but research conducted by a senior research fellow in Arabic and Islamic studies at Pembroke College, has proven that the Yemeni government’s Central Statistical Organisation has for years, for political reasons, manipulated the population figure to 120,000 when in fact there are far more than 350,000 inhabitants just in Al-Mahra alone.[19]

An estimated 700,000 Al Mahri live outside Al-Mahra, and can be found in many countries as far as Malaysia and the US. Most of them live in nearby Middle Eastern countries, the Far East and Africa. Over the past 80 years a significant number of Mehris migrated to Europe, particularly to the UK which is home to a large and fragmented Mehri community of Yemeni origin. Over time there have been many prominent Al Mahri individuals who have achieved noticeable success mainly in the field of politics, and to some extent in the field of business, science and sport. Most prominent and high achieving Mehris were people who live outside Al-Mahra, and some of the most well-known individuals include the fourth President of Sudan- Gaafar Nimeiry, Sulaiman Al Mahri who was a world-famous navigator, Abdelhamid Mehri who was a prominent Algerian politician, and Ahmed Mohammed Al Mahri who is an Emirati professional footballer who plays for both the Baniyas Club and the United Arab Emirates national football team.

The geography of Al-Mahra

The Al Mahra region is quite different from the rest of the Arabian Peninsula where the terrain is desert and barren. Al Mahra has a unique climate where the yearly monsoon gives the land lush valleys, greener forests, and plenty of water. The southeastern part of Al Mahra has the only natural forest in the Arabian Peninsula, which covers parts of Al Mahra and extends over to beyond the Omani border and ends in Dhofar.

The coastal plains throughout Al Mahra are a dry and flat terrain, where the temperature can reach as high as 37 °C (99 °F) and dip as low as 0 °C (32 °F) during the night. The coastal areas of Al Mahra often experience the seasonal monsoon or the Khareef as the local people call it. It lasts from the beginning of June until the end of September. The seasonal monsoon turns the arid hills of the region into a lush, green landscape. Areas affected by the monsoon are shrouded in cooling fog and rain, which lowers the temperature and provides the region with plenty of water. The monsoon is very important to the local Mehri farmers who produce food and grain with the help of sophisticated irrigation. However, when monsoon season ends the landscape reverts into an arid state and the green colors caused by the monsoon disappear.

The temperature

The temperature in the Al Mahra region is lower compared to the rest of Arabian Peninsula where temperature is often as high as 40 °C (104 °F). The temperature in Al-Mahra varies between 22 °C (72 °F) and 35 °C (95 °F) with moderate breezes, but during the monsoon session the temperature can dip to a low of 20 °C (68 °F). As result the humidity increases to between 50% to 75%. The border between Al Mahra and Saudi Arabia is home to the infamous Empty Quarter, which is a treacherous desert that stretches over a large area in the Arabian Peninsula. The temperature in the Empty Quarter can reach as high as 60 °C (140 °F). Al Mahra is also home to the equally well-known Yemeni Highland, which has many valleys and streams providing plenty of water to agricultural communities across the region.

Natural resources

Unlike most Gulf states, Al Mahra does not have any known oil reserves. Throughout history Al Mahra has had an abundance of frankincense and fish.[3] Fish is an essential resource for the people of Al-Mahra and Socotra as 90% of the population depend on fish for living.[3]

Language

The Mehri language is a south Arabian language spoken mainly by the Mahri people living in Al Mahra and abroad. However, the numbers of Mahri speakers are fast declining due to old age, and Al Mahri youth mainly speak Arabic instead of their native language.

Administration and justice system

Al Mahra sultanate was an absolute monarchy like most of countries in the Arabian Peninsula. Currently, the local Mehri sheik enjoy great autonomy as they rule their respective territories of Al Mahra without the interference of the Mehri Sultan or the Yemeni government. The justice system of Al-Mahra is based on the Quran, Sunnah, and age-old Arabic traditions. Each sub-region of Al Mahra and Socotra has autonomous areas with sheikhs and tribal elders who are responsible for all kinds of legal decisions, the enforcement of the rules, and dispute resolutions. Any decisions made by sheikhs and tribal elders are final.

Most of the ruling sultans were of the House of Banu Afrar of Al Mahri and traditionally they resided in the royal palace in Tamrida (now Hadiboh) in Socotra.[3] Hadiboh is now the home of the Abdalla Bin Sultan Issa Al- Afrar who is the current the legitimate pretender to the now defunct Al Mahri throne.

The Banu Afrar dynasty were the Sultans and heads of state of the Al Mahra Sultanate since the 16th century when the sultanate was expanded. The last reining Sultan of Al Mahra was HRH Sultan Abdallah ibn Ashoor Al-Afrar Al-Mahri who is the father of the current pretender of the Al Mahra throne. He was deposed by Arab nationalists who then established the Soviet-supported Marxist Peoples Republic of South Yemen.

Economy

The Al Mahra region is severely underdeveloped as the Yemeni central government has never made any effort to develop the Al-Mahra region which has major potential for economic growth. The rest of Yemen has thousands of kilometers of newly built roads, whilst Al-Mahra and the rest of East Yemen do not have roads as result of tribalism issues. The former government of Ali Abdullah Saleh has diverted development resources and revenues to specific regions inhabited by his own supporters. As a result of the underdevelopment issues in Al-Mahra, most of the region’s economy is based on an informal economy. People either work rearing livestock or in the fishing industry. In addition to the issue of economic underdevelopment, the region is also suffering from a massbrain-drain, which forces large numbers of the educated workforce to leave home and seek employment in Europe or in neighboring Middle Eastern countries.

The Al Mahra region does have a 550 kilometres (340 mi) shoreline and an underdeveloped, but vital, fishing industry which provides employment and food for the local people.[20] The neighboring Dhofar region in Oman, which is considered Al-Mehri territory, is slightly more developed than the Yemeni and Saudi Mehri regions, and the city of Salalah in Dhofar has a thriving hub for container shipping and flourishing tourism attracted by the monsoon season.

The military legacy of Al-Mahra

The people of Al-Mahra played a major role in the history of Islam and the Arab world’s military achievements during the early years of Islam. The Mehri army which took part in the conquest of North Africa and Spain cemented its name in history. The Islamic conquest took place fifteen years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in the year 639, and ended in the year 709 with victory and the Islamic rule of all of North Africa. The Mehri tribe's achievements have been well-documented by historian Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam[21] in his book titled The History of the Conquests of Egypt and North Africa and Spain.

At the beginning of the Muslim conquest of North Africa, the Al-Mahri tribe mostly contributed cavalry to the army. They played a crucial role in the Arab Muslim army under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, who was a well-known Arab military commander and one of the Sahaba ("Companions"). The Al-Mahri army fought alongside him during the Muslim conquest of North Africa, which began with the defeat of the Byzantine imperial forces at the Battle of Heliopolis, and later at the Battle of Nikiou in Egypt in the year 646. The army was a highly skilled cavalry which rode horses and a special camel breed called the Mehri originating from Al-Mahra, and renowned for its speed, agility and toughness.[21] The Al-Mahra army spearheaded the entire Muslim army during the conquest of the city of Alexandria,[21] and it was the first to face the enemies when Alexandria was conquered. The Al-Mahri military success in the Islamic Conquest of North Africa is not a coincidence as young Al-Mahri boys are trained in the art of warfare and self-defence, and such traditions still continue today as the current generation is taught shooting and hand-to-hand combat skills. Presently, Al-Mahra has some of the most lenient gun laws in the world, and because of this most of the men in Al-Mahra own guns and carry the traditional Janbiya dagger in public.

The Al-Mahra army was nicknamed "the people who kill without being killed" by 'Amr ibn al-'As.[21] Commander 'Amr ibn al-'As was amazed by army's ruthlessly efficient warfare whilst sustaining minimal casualties.[21]

As a result of Al-Mahri's success in the Muslim conquest of Egypt, its commander named Abd al-sallam ibn Habira al-Mahri was promoted and he was ordered by 'Amr ibn al-'As to lead the entire Muslim army during the conquest of Libya, which at the time was a Byzantine territory.[21] The army under the command Abd al-sallam ibn Habira al-Mahri defeated the Byzantine imperial army, and the campaign which brought a permanent end to Byzantine rule of Libya. After the Muslim conquest of Egypt, Abd al-sallam ibn Habira al-Mahri was once again promoted as a result of his success as a temporary commander of the entire Muslim army, and he was appointed the first Muslim leader of Libya.

The Muslim conquest of North Africa was temporarily brought to a halt due to Muslim civil wars - better known as the first and second Fitna. The first part of the conquest took place under the Rashidun Caliphate and lasted until the first Muslim civil war erupted between the Quraishi Rashidun Caliphate and a Quraishi rebel force headed by Aisha and Muawiya who brought an end to Rashidun Caliphate. The new Caliph continued with the Muslim conquest of North Africa initiated by his Rashidun predecessor. The army from Al-Mahra continued to be part of the resumed military campaign under the leadership of Caliph Muawiya. During the 660s decade, the Muslim army began the second phase of the Arab invasion of North Africa starting with the invasion of Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia). More than 600 Al-Mahri soldiers carrying the Al-Mahra flag were sent to Ifriqiya, not only to face the usual Byzantine imperial foes, but also to fight new enemies in the form of Berber tribal forces.[21]

Most of the Al-Mahri soldiers who participated in the Muslim conquest of North Africa never returned to Al-Mahra. They chose to settle in the newly colonized North Africa and became part of the Arab speaking population. Descendants of the Al-Mahri army again played a major role in Islamic North Africa, and one of the most notable Al-Mehri individuals was Abdelhamid Mehri who was a resistance fighter who fought the French and became a prominent Algerian politician and government minister.

Several centuries later, another Al-Mahri man called Abu Bekr Mohammed Ibn Ammar Al-Mahri Ash-shilbi, who was a politician from modern day Silves, Portugal, became a prime minister of the Taifa of Seville in Islamic Iberia,[22] and served King Al-mu’atamed Ibn Abbad who was member of Mohammedan Dynasties of Spain. Abu Bekr was highly competent as prime minister, but later he crowned himself king and led a failed rebellion against the Mohammedan Dynasties of Spain. In year 1084, Abu Bekr Mohammed Ibn Ammar Al-Mahri Ash-shilbi was caught and executed by the forces of the Kingdom of Seville.

Places named after Al Mahra and its people

Mehri quarter in Cairo, Egypt

Throughout the Muslim conquest of North Africa the army from Al-Mahra was awarded lands in most of the newly conquered territories. Initially the Mehri tribe was given the region of Jabal Yashkar by the Muslim leadership. This region was located east of the town of Al-Askar which at that time was the capital of Egypt.[23] After the end of Muslim conquest of Egypt in year 641, the well-known Muslim commander, 'Amr ibn al-'As, who led the Muslim army, established the town of Fustat which became the new capital of Egypt. The army was given additional land in the new capital which then became known as Khittat Mahra or the Mahra quarter in English. This land was used by the Mahra forces as a garrison.[21] The Mahra quarter was named after the residents from Al-Mahra as they were the sole owners of the land. Other Arab tribes which were part of the Muslim conquest of Egypt had to share lands. This is the reason why their lands bore a non-tribal name.[21] The Mahra tribe also shared the al-Raya quarter in Fustat with various tribes who were closely associated with the Prophet Muhammad and, according to historical accounts, the Mahra forces used the al-Raya quarter as a residence and stable for their horses.[24] The Mahra quarter was located close to the Al-Raya quarter was which the absolute centre of the new capital of Fustat.

The Mahra quarter continues to exist and is now known as Khittat Mahra. It is located northeast of the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As and is less than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away from the absolute centre of Fustat which is now known as Misr Al Qadimah or Old Cairo in English. The Mahra quarter stretches along most of Salah Salem Street, one of Cairo’s main roads, and is now home to several high-profile destinations including Fustat Park, the National Archives of Egypt, the Museum of Egyptian Civilisation, many residential apartments, and various government offices.

Mehri quarter in the city of Galkayo, Somalia.

There is a 3 square kilometre area in central Galkayo which is known as Xaafada Meheriga in Somali or the Mehri quarter in English. It is the oldest neighbourhood and the absolute city center, and is home to a large Mehri community and many Mehri-owned businesses.

A young Mehri businessman named Maxamud Ali Muse, who had been a high-ranking Italian army officer, commissioned the first building in Galkayo in 1947 which was a warehouse for his wholesale business. At that time Galkayo was no more than a water well where nomadic communities came to water their livestock. Other prominent Mehri businessmen followed suit and established Galkayo as an important market town and transhipment point by establishing wholesale businesses.

Before the 1990 Somali civil war Galkayo was a small town, but after the start of the war, its size has changed dramatically. It became a city overnight as hundreds of thousands of internally displaced individuals fled to Galkayo as a result of the violence in southern Somalia.

Masjid Dian Al-Mahri in Depok, Indonesia

A prominent Indonesian businessman of Mehri origin named Dian Djuriah Maimun Al Rashid commissioned a large mosque called Masjid Dian Al-Mahri in city of Depok in Indonesia in 2001. The mosque is based on a hectare of land and has a capacity for 20,000 worshipers. It is lavishly decorated with expensive building materials imported from abroad such as gold-plated mosaics, large Italian chandeliers, and Italian and Turkish marble.

The mosque has since become one of Depok’s most important tourist attractions, and each day the mosque receives non-Muslim as well as Muslim visitors from all over the world. The visitors are often amazed by the mosque’s design, artworks, garden, and water features.

The rise and fall of the naval forces of Al-Mahra

During the 10th century the Socotra archipelago was annexed by Al-Mahra, and since then a new country called the Sultanate of Al-Mahra and Socotra was officially formed by the sultan. Socotra remained part of new country for more than 500 years until the year 1507 when Portuguese naval forces headed by Tristão da Cunha took control of the archipelago. The invasion cost the Portuguese dearly because of the continuous war with Al-Mahra forces and the harsh weather which led to the loss of many lives and ships.

In 1511 the Sultanate liberated Socotra from the Portuguese and it was once again part of the Sultanate. Al-Mahra’s former naval forces were highly competent and defeated the Portuguese naval forces which, at the time, was considered an undisputed naval superpower. A world-famous Arab navigator named Sulaiman Al Mahri started his illustrious naval career in the Al-Mahra navy. Later in his career he explored the Indian Ocean and wrote several books on the geography of the Indian Ocean and the southeast Asian islands.

During the nineteenth century Al-Mahri naval forces were finally overpowered by British armed forces which employed highly efficient industrial warfare techniques never seen before in Al-Mahra. Al-Mahra became another Third World country - a victim of European aggression. Al-Mahra became a vassal state of Great Britain in the year 1886, and later became part of the Aden Protectorate.

The defeat of Al-Mahra was a great victory for the British government which believed that such a strategy was an important measure needed to protect a vital trade route to British India against the Ottoman Empire. The leadership of Al-Mahra was forced to sign an unfair treaty, and the terms stipulated in the treaty were included that the leadership retained jurisdiction of their land in exchange for British protection.

In 1940 the British government annulled the treaty of 1886 and instead Al-Mahra and its neighboring regions in the Gulf of Aden were forced to sign the so-called Advisory Treaties. Those who refused to sign were subjected to deadly air strikes delivered by the British Royal Air force. The Advisory Treaty meant that the local Mehri leadership no longer had jurisdiction over their internal affairs. The British government now had complete control over internal affairs as well as the order of succession.

Rulers

The Sultans of Mahra had the title of Sultan al-Dawla al-Mahriyya (Sultan Qishn wa Suqutra).[25] They are active politicians nowadays.[26]

Sultans

- c.1750 - 1780 `Afrar al-Mahri

- c.1780 - 1800 Taw`ari ibn `Afrar al-Mahri

- c.1800 - 1820 Sa`d ibn Taw`ari Ibn `Afrar al-Mahri

- c.1834 Sultan ibn `Amr (on Suqutra)

- c.1834 Ahmad ibn Sultan (at Qishn)

- 1835 - 1845 `Amr ibn Sa`d ibn Taw`ari Afrar al-Mahri

- 1845 - 18.. Taw`ari ibn `Ali Afrar al-Mahri

- 18.. - 18.. Ahmad ibn Sa`d Afrar al-Mahri

- 18.. - 18.. `Abd Allah ibn Sa`d Afrar al-Mahri

- 18.. - 18.. `Abd Allah ibn Salim Afrar al-Mahri

- 1875? - 1907 `Ali ibn `Abd Allah Afrar al-Mahri

- 1907 - 1928? `Abd Allah ibn `Isa Afrar al-Mahri

- 1946? - Feb 1952 Ahmad ibn `Abd Allah Afrar al-Mahri

- Feb 1952 - 1967 `Isa ibn `Ali ibn Salim Afrar al-Mahri

Famous Mehri camel

Al-Mahra is home to the Mehri camel which has been integral part Al-Mahra army’s military success during the Islamic conquests of Egypt and North Africa against the Byzantine Empire. During the conquests the cavalry unit from Al-Mahra introduced the Mehri camel to northern Africa, and now it is found throughout the area. It is better known as the Mehari camel in most of northern Africa, and is sometimes also known as the Sahel camel.

It is a special breed originating in Al-Mahra. They are renowned for their speed, agility and toughness. They have a large but slender physique, and because of its small hump it is perfectly suited for ridding.

During the colonial period in northern Africa, the French government took advantage of the Mehri camel’s proven military capabilities, and established a camel corps called the Méhariste which was part of the Armée d'Afrique. It patrolled the Sahara using the Mehri camel. The French Méhariste camel corps was part of the Compagnies Sahariennes the French Army of the Levant.

Car models named after the Mehri camel

In 1968, France’s car maker Citroën introduced the Citroën Méhari, which was a light off-road vehicle named after the famous Mehri camel. The Citroën Méhari was a variant of the Citroën 2CV, and Citroën built more than 144,000 Méhari between 1968 and 1988. A new, 2016 electric model called the Citroën E-Méhari is now being sold in Europe; it is a compact SUV like the Méhari.

The beginning of the end of Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra

In 1862 the Mahra sultanate signed a protectorate treaty with Great Britain after negotiating with the British government, and later Al-Mahra state became part of the Aden Protectorate. The Aden Protectorate was the British government’s effort to secure the trade route to British India. Bringing the area under British control protected a strategically important naval route against the Ottoman Empire. The main point of the treaty was that the rulers retained jurisdiction over their land, and in exchange for British protection, the Al-Mahra sultanate agreed not to enter agreements with, or cede territory to, any other foreign government. Since 1866 the Aden Protectorate meant that nine regions along the Gulf of Aden became vassal states of Great Britain.

In the 1940s Al-Mahra and its neighbouring regions along the Gulf were forced to sign Advisory Treaties,[27] and those who refused were subjected to deadly air strikes delivered by the British Royal Air force. The Advisory Treaty meant that the local leadership no longer had jurisdiction over their internal affairs, and the treaty gave the British government complete control over the nation's internal affairs and the order of succession. The Advisory Treaties caused resentment against British rule and the spread of Arab Nationalism in Al-Mahra and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula. The Treaty was the beginning of the end of the Al-Mahra state, and the end of the centuries-old Al-Mahri monarchy which had managed to overcome superpowers like the Ottomans and the naval power of Portugal. Many in Yemen believe that the British-engineered Advisory Treaty has led to the erosion of Yemen’s traditional power structure, and the current civil war in Yemen is the result of British involvement in the region.

The end of Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra

During the 1960s the British sustained losses against various Egypt-sponsored guerrilla forces and the Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY). In 1963 the British government declared a state of emergency in the Aden Protectorate, and by 1967 the British forces had left Yemen as a result of losses against the National Liberation Front (Yemen) which later seized power in Al-Mahra. In 1967, the Al-Mahra sultanate was absorbed by the Marxist People's Republic of South Yemen which itself was an entity heavily sponsored by the Soviets.[27] They put an end to the centuries-old Al-Mahri sultanate. Sultan Issa Bin Ali Al-Afrar Al-Mahri was the last reigning Al-Mahri Sultan of Qishn and Socotra.

The sultanate was abolished in 1967 and was annexed by Soviet supported South Yemen, which itself later united with North Yemen to become unified Yemen in 1990. In 2014 the land which was formerly known as the Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra was absorbed into a new region called Hadramaut,[28] and this reform has angered many in Al-Mahra who now believe that the Yemeni government is further centralizing its grip on power.

Current issues in the land formerly known as Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra

Support for Al-Mahra independence

Traditionally, the leadership of Al-Mahra has never had a good relationship with the central government of Yemen which they see as occupiers. The ongoing lawlessness and terrorism issues in other areas of Yemen have further strained relations between the two. Since Al-Mahra was annexed by South Yemen in 1967, successive Yemeni governments, including the current one, have made no effort to develop the region's economy, and as a result of this discrimination there are no modern roads, education facilities or any other economically vital infrastructure in the region.

The Yemeni government has created six large federal states which replaced the existing twenty-two regions of Yemen, and this reform has further alienated many in Southern Yemen including Al-Mahra and Socotra.[28] People believe that creation of large federal states will lead to further centralisation of power in Yemen and further marginalisation of the regions in Southern Yemen which have already been neglected by the central government for decades. It is not the only region that does not receive any income from the central government due to rampant corruption demonstrated by the Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi administration. In many places in South Yemen, the government has lost credibility because of the way it is handling the Houthi-crisis. The voices calling for independence from Yemen are growing in the region.[29]

The people of Al-Mahra have lost confidence in the Yemeni government which failed to deal with the political and security chaos taking place,[30] and the chaotic situation in the country has increased the voices of pro-secession in the Al- Mahra region who are calling for to Al-Mahra to once again become an independent state. A 2014 study carried out by a researcher at Oxford University concluded that 89% of the population of Al Mahra are disenfranchised by the central Yemeni government.[31] The same research concluded that 86% of the people of Al Mahra support an independent Al-Mahra state.

The central Yemeni government does not have control of most of the country, including Al-Mahra which is under the control of tribal leadership who maintain law and order based age-old traditions and customs. At the moment, the Al-Mahra and Socotra regions are relatively peaceful compared to the rest of Yemen, and they are currently hosting thousands of refugees who fled the conflicts in Yemen, Somalia, and Syria. The Shi’ite Houthi rebels and Al-Qaida are now causing conflicts and instability in most of the country,[29] and the Houthi-Saudi conflict has already caused a humanitarian crisis in the rest of the country in the form of food and water shortages, which is the reason why thousands of refugees and internally displaced people are seeking refuge in Al-Mahra.

Community driven anti-terrorism effort

Al-Mahra does not have terrorism issues but the rest of Yemen has become a well-established breeding ground for Al-Qaida affiliates who use the country as a training facility for would-be terrorists. There has been one terror-related incident in Al-Mahra where terrorists had been seeing fleeing to the region,[32] but since this incident there have been no more terror related activities thanks to efforts made by local people and tribal leadership who carry out privately funded anti-terrorism efforts.

In the beginning of 2014 a lost US drone crashed into Al-Mahra,[32] and the wreckage was taken to a local military base. This incident was the first of its kind, and it was the first time people in the region had seen a drone or any terrorism-related activity. Unlike most of Yemen, there are no terror related activities in Al-Mahra and most of the US drone strikes take place in other areas such as Abyan, Shabwa, Hadramout, and Al-Beida’a where there is strong Al-Qaeda presence.

The government has proven to be unable to eradicate terrorism in Yemen as the country’s leadership does not have control over the army. Ordinary Al-Mahra people have made great efforts to prevent terrorism in their own territory, and everywhere in the Al-Mahra region there are tribal militias who carry out methodical patrols and take anti-terrorist measures in an effort to prevent incursion by Al-Qaeda who are present in the neighbouring regions. These anti-terrorism activities are self-funded and neither the people nor the local leadership receive assistance from the international community or from the Yemeni government. There are on-going anti-terrorism patrols throughout Al-Mahra, and these patrols are often seen in cities and rural areas, conducting regular searches and manning checkpoints at Al-Mahra’s borders in order to stop Saudi fighters who regularly cross the Yemeni border to join Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Invasion of Al Mahra and Socotra by the Saudi- led coalition

At the beginning of year 2017, the armed forces of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) who are part of the Saudi-led coalition secretly built military bases in Socotra and later invaded the Island by importing military hardware [33]. Emirati soldiers carried out swift military operation on third of May 2018 and took over local government offices, the airport, and the seaport; and Yemeni civil servants, military and police personnel where evicted from all government buildings. The local eyewitness described that all the government buildings and main streets are now adorned with UAE flags and the pictures of Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, and the UAE armed forces deployed heavily armed military personnel on the streets as a show of force aimed at the indigenous people. The Island of Socotra which had enjoyed years of peace and stability had been dragged into the chaos in the mainland Yemen by the UAE forces and the Saudi-coalition, and thus refuse to obey the people of Al Mahra’s wish to be free from Saudi-led chaos in the mainland Yemen.

The UAE forces were already present in the mainland and Al Mahra prior the invasion of Socotra, and their presence in the region is not welcomed by the indigenous people as the coalition forces has no reason since there is no Houthi presence in both Al Mahra and Socotra. However, this did not prevent them to setup military base under false pretense of prevention of Iran weapon smuggling through Al Mahra. As a result of proxy war in Yemen, Al Mahra too is becoming another venue for Saudi Iran proxy war as various countries are now supporting certain factions, for example, the Saudis and UAE are respective supporting Hadi loyalists and Southern Movement called the Southern Transitional Council (also known as Mahri Elite Forces), who both are faction with no legitimate connection with Al Mahra; whilst indigenous Al Mahri people who have ambition of distancing themselves from the chaos and uncertainty in Yemen through independence, are being supported by Oman who want to keep Al Mahra peaceful in order to protect its borders [34].

The UAE government justify their presence in the island as a part of supporting the Yemeni government headed by the president Hadi, but the Yemeni government refuted the UAE claim and reject the military presence in the island and stated that the UAE’s unwelcome presence is undermining the government’s rule [35]. The prime minister of Yemen was among protesters in the street who were protesting against the presence of UAE forces in island of Socotra.

Previously, Saudi-led offences were mainly focused in Houthi regions, but UAE who have ambition of extending its influence in Yemen decided to turn against its Yemeni government ally by financially supporting and reviving the Southern Movement and further weakening the Yemeni government [36]. The relation between the Yemenis and the UAE government had soured [37] as a result of UAE support of South Yemen secessionist, and the ongoing UAE invasion of Socotra and Al Mahra is further escalating the ongoing problem. Even Socotra’s UNESCO protected nature had been negatively affected by the presence of UAE forces who were seen stealing and disturbing protected plan and wildlife in the island [38] as the Emirati government are making way for the building of infrastructure which enable damaging mass tourism.

A major British named the Independent who carried out an investigative report of the UAE invasion of the island of Socotra [39] revealed that the UAE who took control the island had turned the island into military outpost and holiday resort and renovated some of the infrastructure before their arrival. The invasion of Socotra intensified the call for independence and reinstatement of the Al Mahri monarchy who are seen as the best solution for Socotra and Al Mahra as other alternatives in the form of Yemeni government and Saudi-led coalition proved to be failed experiments. It had been reported that the Saudi government are also concerned about UAE’s expansionist policies as South Yemen secessionist militias funded by the UAE had clashed with government militias funded by the Saudis, and the coalition’s presence is becoming even more farcical.

It had been reported Al-Mahra and Socotra People's General Council, which includes tribal elders and the current pretender to the Al Mahri throne had reported the pointless Saudi-led coalition in Al Mahra and Socotra to the UN and are sending representatives to Permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. The ambition of the Al-Mahra and Socotra People's General Council is to distance itself from devastating and pointless proxy war in the mainland Yemen; which so far claimed thousands of innocent civilians lives and led to the destruction of the country, but the presence of foreign military in both Al Mahra and Socotra proves that these peaceful regions are already dragged into the proxy war against their will [40].

Al-Mahra in popular culture

A British romantic comedy called Salmon Fishing in the Yemen starring Ewan McGregor, is loosely based on real-life events in the Al-Mahra region. Al-Mahra is the only place in Yemen with a milder climate and plentiful water, but it remains to be seen whether salmon can survive there.

King Shaddad was a character in the Arabian folk tales One Thousand and One Nights. Shaddad, his brother and their father were mentioned in the 227th to 229th nights of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. According to the tales, King Shaddad was a highly competent king who built the pillared city of Iram. In the book he is portrayed as a brutal king who ruled all of Arabia and Iraq. Modern day Al-Mahra in Yemen and Dhofar in Oman were part of the Ād Kingdom; they are still inhabited by the Mehri tribe who are the only descendants of the ancient people of 'Ad.

See also

References

- ↑ Paul Dresch. A History of Modern Yemen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ↑ "Yemen to become federation of six regions". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mahra Sultanate". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ Ibrahim, edited by Moawiyah M. (1989). Arabian studies in honour of Mahmoud Ghul : symposium at Yarmouk University, December 8-11, 1984. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447027967.

- ↑ Ibn al-Mujawir (1996). Sifat bilad al-yaman wa-makah wa ba’d al-hijaz … tarikh al-mustabir. Cairo: Maktabat al-Thaqafat al-Diniyah.

- ↑ Al-Mahri, Salim Yasir (1983). Bilad al-Mahra: Madiha wa hadiruha.

- ↑ Donzel, E. van (1994). Islamic desk reference : compiled from the encyclopaedia of islam (New ed.). Leiden u.a.: Brill. p. 483. ISBN 9789004097384.

- ↑ Crosby, Elise W. (2007). The history, poetry, and genealogy of the Yemen : the Akhbar of Abid b. Sharya al-Jurhumi (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781593333942.

- ↑ Crosby, Elise W. (2007). The history, poetry, and genealogy of the Yemen : the Akhbar of Abid b. Sharya al-Jurhumi (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 75. ISBN 9781593333942.

- ↑ Sperl, Stefan (1989). Mannerism in Arabic poetry : a structural analysis of selected texts : 3rd century AH/9th century AD-5th century AH/11th century AD (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 9780521354851.

- ↑ Sperl, Stefan, ed. (1996). Qasida poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa. Leiden: Brill. p. 138. ISBN 9789004102958.

- ↑ Thackston, Wheeler M. (2001). Album prefaces and other documents on the history of calligraphers and painters. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. p. 7. ISBN 9789004119611.

- ↑ Parolin, Gianluca P. (2009). Citizenship in the Arab world : kin, religion and nation-state. [Amsterdam]: Amsterdam University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-9089640451.

- ↑ De Lacy O'Leary (2001). Arabia Before Muhammad. p. 18.

- ↑ Sweat, John (5 February 2006). "The People of 'Ad". The Anthropogene.

- ↑ Wilford, J.N. (5 February 1992). "On the Trail From the Sky: Roads Point to a Lost City". New York Times.

- ↑ Qureshi, Sultan Ahmed (2005). Letters Of The Holy Prophet Muhammad. . IDARA ISHA'AT-E-DINIYAT (P) LTD.

- 1 2 Ella Landau-Tasseron. The History of al-Tabari Vol. 39: Biographies of the Prophet's Companions and Their Successors: al-Tabari's Supplement to His History. SUNY Press.

- ↑ Lei Win, Thin. "INTERVIEW -East Yemen Risks Civil War And Humanitarian Crisis, Says UK Expert". Thomson Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Mahra Sultanate | Historical State, Yemen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥakam (1922). Kitāb futuḥ misr wa akbārahā, edited and with English preface by Charles Torrey (English title The History of the Conquests of Egypt, North Africa, and Spain). Yale University Press.

- ↑ al-Maqqarī, Aḥmad Ibn-Muḥammad (1964). The History Of The Mohammedan Dynasties In Spain. New York: Johnson. p. 341.

- ↑ Gil, Moshe (1976). Documents Of The Jewish Pious Foundations From The Cairo Geniza.

- ↑ Grabar, Oleg (1989). Muqarnas. Leiden.

- ↑ States of the Aden Protectorates Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Federal challenge: Yemen's turbulence may have opened a door for the return of the sultans". The National. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- 1 2 Halliday, Fred (2013). Arabia Without Sultans. New York: Saqi.

- 1 2 "Yemen to become federation of six regions". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 Al-Arashi, Fakhri. "Al-Mahra: In East Yemen Still Looking For The Governor Successor To Be Appointed". National Yemen. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Al-Moshki, Ali. "Taking Yemen from bad to worse". Yemen Times. Yemen Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Kendall, Elisabeth. "Yemen's Eastern Province: The people of Mahra clearly want independence". Oxpol Oxford University Politics Blog. Oxpol Oxford University Politics Blog. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- 1 2 Al-Maqtari, Muaad. "Oman investigates infiltration of border by Al-Qaeda affiliated Ansar Al-Sharia". Yemen Times. Yemen Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ "Yemenis protest against UAE presence in Socotra". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Ardemagni, Eleonora. "Emiratis, Omanis, Saudis: the rising competition for Yemen's Al Mahra". Middle East Centre Blog. London School of Economics. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "Yemenis protest against UAE presence in Socotra". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "UAE extends military reach in Yemen and Somalia". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "Yemenis protest against UAE presence in Socotra". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ McKernan, Bethan; Towers, Lucy. "Socotra is finally dragged into Yemen's civil war, ripping apart the island's way of life". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ McKernan, Bethan; Towers, Lucy. "Socotra is finally dragged into Yemen's civil war, ripping apart the island's way of life". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ McKernan, Bethan; Towers, Lucy. "Socotra is finally dragged into Yemen's civil war, ripping apart the island's way of life". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 13 May 2018.