Human capital flight

Human capital flight refers to the emigration of individuals who have received advanced training at home. The net benefits of human capital flight for the receiving country are sometimes referred to as a "brain gain" whereas the net costs for the sending country are sometimes referred to as a "brain drain".[1] In occupations that experience a surplus of graduates, immigration of foreign-trained professionals can aggravate the underemployment of domestic graduates.[2]

Research shows that there are significant economic benefits of human capital flight both for the migrants themselves and those who remain in the country of origin.[3][4][5][6][7] It has been found that emigration of skilled individuals to the developed world contributes to greater education and innovation in the developing world.[8][9][10][11][12] Research also suggests that emigration, remittances and return migration can have a positive impact on democratization and the quality political institutions in the country of origin.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

Types

There are several types of human capital flight:

- Organizational: The flight of talented, creative, and highly qualified employees from large corporations that occurs when employees perceive the direction and leadership of the company to be unstable or stagnant, and thus, unable to keep up with their personal and professional ambitions.

- Geographical: The flight of highly trained individuals and college graduates from their area of residence.

- Industrial: The movement of traditionally skilled workers from one sector of an industry to another.

As with other human migration, the social environment is often considered to be a key reason for this population shift. In source countries, lack of opportunities, political instability or oppression, economic depression, health risks and more contribute to human capital flight, whereas host countries usually offer rich opportunities, political stability and freedom, a developed economy and better living conditions that attract talent. At the individual level, family influences (relatives living overseas, for example), as well as personal preferences, career ambitions and other motivating factors, can be considered.

Origins and uses

The term "brain drain" was coined by the Royal Society to describe the emigration of "scientists and technologists" to North America from post-war Europe.[22] Another source indicates that this term was first used in the United Kingdom to describe the influx of Indian scientists and engineers.[23] Although the term originally referred to technology workers leaving a nation, the meaning has broadened into "the departure of educated or professional people from one country, economic sector, or field for another, usually for better pay or living conditions".[24]

"Brain-drain‟ is a phenomenon where, relative to the remaining population, a substantial number of more educated (numerate, literate) persons emigrate.[25]

Given that the term brain drain is a pejorative and implies that skilled emigration is bad for the country of origin, some scholars recommend against using the term in favor of more neutral and scientific terms.[26][27] After all, research indicates that there may be net human capital gains, a "brain gain", for the sending country in opportunities for emigration.

Impact

The positive effects of human capital flight are sometimes referred to as "brain gain" whereas the negative effects are sometimes referred to as "brain drain". The notion of the "brain drain" is largely unsupported in the academic literature. According to economist Michael Clemens, it has not been shown that restrictions on high-skill emigration reduce shortages in the countries of origin.[28] According to development economist Justin Sandefur, "there is no study out there... showing any empirical evidence that migration restrictions have contributed to development."[29] Hein de Haas, Professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam, describes the brain drain as a "myth".[30][31] However, according to Catholic University of Louvain economist Frederic Docquier, human capital flight has an adverse impact on most developing countries, even if it can be beneficial for some developing countries.[32] Whether a country experiences a "brain gain" or "brain drain" depends on factors such as composition of migration, level of development, and demographic aspects including its population size, language, and geographic location.[32]

Economic effects

Research suggests that migration (both low-and high-skilled) is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.[33][34][35][36] According to one study, welfare increases in both types of countries: "welfare impact of observed levels of migration is substantial, at about 5% to 10% for the main receiving countries and about 10% in countries with large incoming remittances".[33] According to economists Michael Clemens and Lant Pratchett, "permitting people to move from low-productivity places to high-productivity places appears to be by far the most efficient generalized policy tool, at the margin, for poverty reduction".[37] A successful two-year in situ anti-poverty program, for instance, helps poor people make in a year what is the equivalent of working one day in the developed world.[37] Research on a migration lottery that allowed Tongans to move to New Zealand found that the lottery winners saw a 263% increase in income from migrating (after only one year in New Zealand) relative to the unsuccessful lottery entrants.[38] A 2017 study of Mexican immigrant households in the United States found that by virtue of moving to the United States, the households increase their incomes more than fivefold immediately.[39] The study also found that the "average gains accruing to migrants surpass those of even the most successful current programs of economic development."[39]

Remittances increase living standards in the country of origin. Remittances are a large share of GDP in many developing countries,[40][40][41] and have been shown to increase the wellbeing of receiving families.[42] In the case of Haiti, the 670,000 adult Haitians living in the OECD sent home about $1,700 per migrant per year. That’s well over double Haiti’s $670 per capita GDP.[29] A study on remittances to Mexico found that remittances lead to a substantial increase in the availability of public services in Mexico, surpassing government spending in some localities.[43] A 2017 study found that remittances can significantly alleviate poverty after natural disasters.[44] Research shows that more educated and higher earning emigrants remit more.[45] Some research shows that the remittance effect is not strong enough to make the remaining natives in countries with high emigration flows better off.[46] A 2016 NBER paper suggests that emigration from Italy in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis reduced political change in Italy.[47]

Return migration can also be a boost to the economy of developing states, as the migrants bring back newly acquired skills, savings and assets.[48]

Studies show that the elimination of barriers to migration would have profound effects on world GDP, with estimates of gains ranging between 67–147.3%.[49][50][51] Research also finds that migration leads to greater trade in goods and services between the sending and receiving countries.[52][53][54] Using 130 years of data on historical migrations to the United States, one study finds "that a doubling of the number of residents with ancestry from a given foreign country relative to the mean increases by 4.2 percentage points the probability that at least one local firm invests in that country, and increases by 31% the number of employees at domestic recipients of FDI from that country. The size of these effects increases with the ethnic diversity of the local population, the geographic distance to the origin country, and the ethno-linguistic fractionalization of the origin country."[55] Emigrants have been found to significantly boost foreign direct investment (FDI) back to their country of origin.[56][57][58] According to one review study, the overall evidence shows that emigration helps developing countries integrate into the global economy.[59]

A 2016 study reviewing the literature on migration and economic growth "shows that migrants contribute to the integration of their country into the world market, which can be particularly important for economic growth in developing countries."[60] Research suggests that emigration causes an increase in the wages of those who remain in the country of origin. A 2014 survey of the existing literature on emigration finds that a 10 percent emigrant supply shock would increase wages in the sending country by 2–5.5%.[61] A study of emigration from Poland shows that it led to a slight increase in wages for high- and medium-skilled workers for remaining Poles.[62] A 2013 study finds that emigration from Eastern Europe after the 2004 EU enlargement increased the wages of remaining young workers in the country of origin by 6%, while it had no effect on the wages of old workers.[63] The wages of Lithuanian men increased as a result of post-EU enlargement emigration.[64] Return migration is associated with greater household firm revenues.[65]

Education and innovation

Research finds that emigration and low migration barriers has net positive effects on human capital formation in the sending countries.[66][67][68][69][70] This means that there is a "brain gain" instead of a "brain drain" to emigration. One study finds that sending countries benefit indirectly in the long-run on the emigration of skilled workers because those skilled workers are able to innovate more in developed countries, which the sending countries are able to benefit on as a positive externality.[71] Greater emigration of skilled workers consequently leads to greater economic growth and welfare improvements in the long-run.[71] According to economist Michael Clemens, it has not been shown that restrictions on high-skill emigration reduce shortages in the countries of origin.[28]

A 2017 paper found that the emigration opportunities to the United States for high-skilled Indians provided by the H-1B visa programme contributed to the growth of the Indian IT sector.[36][72] A greater number of Indians were induced to enroll in computer science programs in order to move to the United States, and a large number of these Indians never moved to the United States (due to caps in the H-1B programme) or returned to India after the completion of their visas.[36][72] One 2011 study finds that emigration has mixed effects on innovation in the sending country, boosting the number of important innovations but reducing the number of average inventions.[73]

Democracy, human rights and liberal values

Research also suggests that emigration, remittances and return migration can have a positive impact on political institutions and democratization in the country of origin.[74][75][76][77][78][79][79][80][81][82][83] Research shows that exposure to emigrants boosts turnout.[84][85] Research also shows that remittances can lower the risk of civil war in the country of origin.[86] Migration leads to lower levels of terrorism.[87] Return migration from countries with liberal gender norms has been associated with the transfer of liberal gender norms to the home country.[88][89][90] A 2009 study finds that foreigners educated in democracies foster democracy in their home countries.[91] Studies find that leaders who were educated in the West are significantly more likely to improve their country's democracy prospects.[92][93] A 2016 study found that Chinese immigrants exposed to Western media censored in China became more critical of their home government’s performance on the issues covered in the media and less trusting in official discourse.[94] A 2014 study found that remittances decreased corruption in democratic states.[95]

A 2015 study finds that the emigration of women in rural China reduces son preference.[96]

Historical examples

Neoplatonic academy philosophers move

After Justinian closed the Platonic Academy in AD 529, according to the historian Agathias, its remaining members sought protection from the Sassanid ruler, Khosrau I, carrying with them precious scrolls of literature, philosophy, and to a lesser degree, science. After the peace treaty between the Persian and the Byzantine empires in 532 guaranteed their personal security, some members of this group found sanctuary in the Pagan stronghold of Harran, near Edessa. One of the last leading figures of this group was Simplicius, a pupil of Damascius, the last head of the Athenian school. The students of an academy-in-exile may have survived into the ninth century, long enough to facilitate the Arabic revival of the Neoplatonist commentary tradition in Baghdad.[97]

Spanish expulsion of Jews and Moors

After the end of the Catholic reconquest of Spain, the Catholic Monarchs pursued a religiously uniform kingdom. Jews were expelled from the country in 1492. As they dominated financial services in the country, their expulsion was instrumental in causing future economic problems, for example the need for foreign bankers such as the Fugger family and others from Genoa. On 7 January 1492, the King ordered the expulsion of all the Jews from Spain — from the kingdoms of Castile, Catalonia, Aragon, Galicia, Majorca, Minorca, the Basque provinces, the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, and the Kingdom of Valencia. Before that, the Queen had also expelled them from the Kingdom of Andalusia.[98]

The war against Turks and North African Moors affected internal policy in the uprising of the Alpujarras (1568–1571) and motivated the expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609. Despite being a minority group, they were a key part of the farming sector and trained artisans. Their departure contributed to economic decline in some regions of Spain. This way, the conservative aristocracy increased its power over economically developed provinces.

Huguenot exodus from France (17th century)

In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes and declared Protestantism to be illegal in the Edict of Fontainebleau. After this, many Huguenots (estimates range from 200,000 to 1,000,000[99]) fled to surrounding Protestant countries: England, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark and Prussia — whose Calvinist great elector, Frederick William, welcomed them to help rebuild his war-ravaged and under-populated country. Many went to the Dutch colony at the Cape (South Africa), where they were instrumental in establishing a wine industry.[100] At least 10,000 went to Ireland, where they were assimilated into the Protestant minority during the plantations.

Many Huguenots and their descendants prospered. Henri Basnage de Beauval fled France and settled in the Netherlands, where he became an influential writer and historian. Abel Boyer, another noted writer, settled in London and became a tutor to the British Royal Family. Henry Fourdrinier, the descendant of Huguenot settlers in England, founded the modern paper industry. Augustin Courtauld fled to England, settling in Essex and established a dynasty that founded the British silk industry. Noted Swiss mathematician Gabriel Cramer was born in Geneva to Huguenot refugees. Sir John Houblon, the first Governor of the Bank of England, was born into a Huguenot family in London. Isaac Barré, the son of Huguenot settlers in Ireland, became an influential British soldier and politician. Gustav and Peter Carl Fabergé, the descendants of Huguenot refugees, founded the world-famous Fabergé company in Russia, maker of the famous Faberge eggs.

The exodus of Huguenots from France created a brain drain, as Huguenots accounted for a disproportionate number of entrepreneurial, artisan, and technical occupations in the country. The loss of this technical expertise was a blow from which the kingdom did not fully recover for many years.

19th century Eastern Europe migration

Mid-19th century Eastern European migration was significantly shaped by religious factors. The Jewish minority experienced strong discrimination in the Russian Empire during this period, which reached its maximum in the pogrom waves of the 1880s. During the 1880s, the mass exodus of more than two million Russian Jews began. Already before, a migration stream of Jewish people started which was characterized by highly skilled individuals. This pronounced selectivity was not caused by economic incentives, but by political persecution.[25]

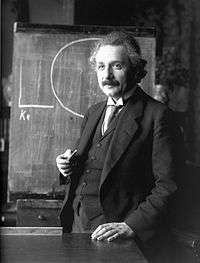

Antisemitism in pre-World War II Europe (1933–1943)

Antisemitic feelings and laws in Europe through the 1930s and 1940s, culminating in the Holocaust, caused an exodus of intelligentsia. Notable examples are:

- Albert Einstein (emigrated permanently to the United States in 1933)

- Sigmund Freud (finally decided to emigrate permanently with his wife and daughter to London, England, in 1938, two months after the Anschluss)

- Enrico Fermi (1938; though he was not Jewish himself, his wife, Laura, was)

- Niels Bohr (1943; his mother was Jewish)

- Theodore von Karman

- John von Neumann

Besides Jews, Nazi persecution extended to liberals and socialists in Germany, further contributing to emigration. Refugees in New York City founded the University in Exile. The Bauhaus, perhaps the most important arts and design school of the 20th century, was forced to close down during the Nazi regime because of their liberal and socialist leanings, which the Nazis considered degenerate. The school had already been shut down in Weimar because of its political stance, but moved to Dessau prior to the closing. Following this abandonment, two of the three pioneers of modern architecture, Mies Van Der Rohe and Walter Gropius, left Germany for America (while Le Corbusier stayed in France). They introduced the European Modern movement to the American public and fostered the international style in architecture and design, helping to transform design education at American universities and influencing later architects. A 2014 study in the American Economic Review found that German Jewish Émigrés in the US boosted innovation in the US.[101]

Hungarian Scientists in the Early and Mid 20th Century

"The Martians" were a group of prominent Hungarian scientists of Jewish descent (mostly, but not exclusively, physicists and mathematicians) who emigrated to the United States during and after World War II due to Nazism or Communism. They included, among others, Theodore von Kármán, John von Neumann, Paul Halmos, Eugene Wigner, Edward Teller, George Pólya, John G. Kemeny and Paul Erdős. Several were from Budapest, and were instrumental in American scientific progress (e.g., developing the atomic bomb).

Former Nazi Scientist recruitment by Both the US and the USSR Post WW2

In the last months of and post WW2 both the US and USSR forcibly recruited and transported thousands of former Nazi scientists to the US and USSR respectively to continue their scientific work in those countries.

Eastern Europe under Eastern Bloc

By 1922, the Soviet Union had issued restrictions making emigration of its citizens to other countries almost impossible.[102] Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev later stated, "We were scared, really scared. We were afraid the thaw might unleash a flood, which we wouldn't be able to control and which could drown us. How could it drown us? It could have overflowed the banks of the Soviet riverbed and formed a tidal wave which would have washed away all the barriers and retaining walls of our society."[103] After Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II, the majority of those living in the countries of the Eastern Bloc aspired to independence and wanted the Soviets to leave.[104] By the early 1950s, the approach of the Soviet Union to restricting emigration was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc, including East Germany.[105]

Even after the closing of the Inner German border officially in 1952,[106] the border between the sectors of East Berlin and West Berlin remained considerably more accessible than the rest of the border because it was administered by all four occupying powers.[107] The Berlin sector border was essentially a "loophole" through which East Bloc citizens could still emigrate.[106] The 3.5 million East Germans, called Republikflüchtlinge, who had left by 1961 totalled approximately 20% of the entire East German population.[108] The emigrants tended to be young and well-educated, leading to the brain drain feared by officials in East Germany.[104] Yuri Andropov, then the CPSU director of Relations with Communist and Workers' Parties of Socialist Countries, decided on 28 August 1958 to write an urgent letter to the Central Committee about the 50% increase in the number of East German intelligentsia among the refugees.[109] Andropov reported that, while the East German leadership stated that they were leaving for economic reasons, testimony from refugees indicated that the reasons were more political than material.[109] He stated, "the flight of the intelligentsia has reached a particularly critical phase."[109] The direct cost of labour force losses has been estimated at $7 billion to $9 billion, with East German party leader Walter Ulbricht later claiming that West Germany owed him $17 billion in compensation, including reparations as well as labour force losses.[108] In addition, the drain of East Germany's young population potentially cost it over 22.5 billion marks in lost educational investment.[110] In August 1961, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded by construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.[111]

By region

Europe

Human capital flight phenomena in Europe fall into two distinct trends. The first is an outflow of highly qualified scientists from 'Western Europe' mostly to the United States.[112] The second is a migration of skilled workers from 'Central' and 'Southeastern Europe' into 'Western Europe', within the EU.[113] While in some countries the trend may be slowing,[114][115] certain Southeast European countries such as Italy continue to experience extremely high rates of human capital flight.[116] The European Union has noted a net loss of highly skilled workers and introduced a "blue card" policy – much like the American green card – which "seeks to draw an additional 20 million workers from Asia, Africa and the Americas in the next two decades".[117]

Although the EU recognises a need for extensive immigration to mitigate the effects of an aging population,[118] nationalist political parties have gained support in many European countries by calling for stronger laws restricting immigration.[119] Immigrants are perceived as a burden on the state and cause of social problems like increased crime rates and major cultural differences.[120]

Western Europe

In 2006, over 250,000 Europeans emigrated to the United States (164,285),[121] Australia (40,455),[122] Canada (37,946)[123] and New Zealand (30,262).[124] Germany alone saw 155,290 people leave the country (though mostly to destinations within Europe). This is the highest rate of worker emigration since reunification, and was equal to the rate in the aftermath of World War II.[125] Portugal has experienced the largest human capital flight in Western Europe. The country has lost 19.5% of its qualified population and is struggling to absorb sufficient skilled immigrants to compensate for losses to Australia, Canada, Switzerland, Germany and Austria.[126]

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern European countries have expressed concerns about extensive migration of skilled labourers to Ireland and the United Kingdom. Lithuania, for example, has lost about 100,000 citizens since 2003, many of them young and well-educated, to emigration to Ireland in particular. (Ireland itself used to experience high rates of human capital flight to the United States, Great Britain and Canada before the Celtic Tiger economic programmes.) A similar phenomenon occurred in Poland after its entry into the European Union. In the first year of its EU membership, 100,000 Poles registered to work in England, joining an estimated 750,000 residents of Polish descent.[127] Research conducted by PKO Bank Polski, Poland's largest retail bank, shows that 63% of Polish immigrants to the UK were aged between 24 and 35, with 40% possessing a university degree.[128] However, with the rapid growth of salaries in Poland, its booming economy, the strong value of the złoty, and decreasing unemployment (which fell from 14.2% in May 2006 to 8% in March 2008[129]), the flight of Polish workers slowed.[130] In 2008 and early 2009 people who came back outnumbered those leaving the country. The exodus is likely to continue, however.[131]

Southeastern Europe

The rapid but small-scale departure of highly skilled workers from Southeastern Europe has caused concern about those nations developing towards inclusion in the European Union.[132] This has sparked programmes to curb the outflow by encouraging skilled technicians and scientists to remain in the region to work on international projects.[133]

Serbia is one of the top countries that have experienced human capital flight from the fall of communist regime. In 1991, people started emigrating to the closest countries, Italy and Greece, and with the passing of years began going farther, to the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States. In the last 10 years, educated people and professionals have been leaving the country and going to other countries where they feel they can have better possibilities for better and secure lives. This is a concern for Albania as well, as it is losing its skilled-workers and professionals.

Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain

Many citizens of the countries most stricken by the economic crisis in Europe have emigrated, many of them to Australia, Brazil, Germany, United Kingdom, Chile, Ecuador, Angola and Argentina.[134][135]

Turkey

In the 1960s, many skilled and educated people emigrated from Turkey, including many doctors and engineers. This emigration wave is believed to have been triggered by political instability, including the 1960 military coup. In later decades, into the 2000s, many Turkish professionals emigrated, and students studying overseas chose to remain abroad, mainly due to better economic opportunities. This human capital flight was given national media attention, and in 2000, the government formed a task force to investigate the "brain drain" problem.[136]

United Kingdom

There are a considerable number of people leaving the United Kingdom for other countries, especially Australia and the United States.[137]

Business industries expressed worries that Brexit poses significant risk of causing brain drain.[138]

Africa

Countries in Africa have lost a tremendous amount of their educated and skilled populations as a result of emigration to more developed countries, which has harmed the ability of such nations to get out of poverty. Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia are believed to be the most affected. According to the United Nations Development Programme, Ethiopia lost 75% of its skilled workforce between 1980 and 1991.

South African President Thabo Mbeki said in his 1998 'African Renaissance' speech:

"In our world in which the generation of new knowledge and its application to change the human condition is the engine which moves human society further away from barbarism, do we not have need to recall Africa's hundreds of thousands of intellectuals back from their places of emigration in Western Europe and North America, to rejoin those who remain still within our shores!

I dream of the day when these, the African mathematicians and computer specialists in Washington and New York, the African physicists, engineers, doctors, business managers and economists, will return from London and Manchester and Paris and Brussels to add to the African pool of brain power, to enquire into and find solutions to Africa's problems and challenges, to open the African door to the world of knowledge, to elevate Africa's place within the universe of research the information of new knowledge, education and information."

Africarecruit is a joint initiative by NEPAD and the Commonwealth Business Council to recruit professional expatriate Africans to take employment back in Africa after working overseas.[139]

In response to growing debate over the human capital flight of health care professionals, especially from lower income countries to some higher income countries, in 2010 the World Health Organization adopted the Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, a policy framework for all countries for the ethical international recruitment of doctors, nurses and other health professionals.

African human capital flight has begun to reverse itself due to rapid growth and development in many African nations, and the emergence of an African middle class. Between 2001 and 2010, six of the world's ten fastest-growing economies were in Africa, and between 2011 and 2015, Africa's economic growth is expected to outpace Asia's. This, together with increased development, introduction of technologies such as fast Internet and mobile phones, a better-educated population, and the environment for business driven by new tech start-up companies, has resulted in many expatriates from Africa returning to their home countries, and more Africans staying at home to work.[140]

Ghana

The trend for young doctors and nurses to seek higher salaries and better working conditions, mainly in higher income countries of the West, is having serious impacts on the health care sector in Ghana. Ghana currently has about 3,600 doctors—one for every 6,700 inhabitants. This compares with one doctor per 430 people in the United States.[141] Many of the country's trained doctors and nurses leave to work in countries such as Britain, the United States, Jamaica and Canada. It is estimated that up to 68% of the country's trained medical staff left between 1993 and 2000, and according to Ghana's official statistics institute, in the period 1999 to 2004, 448 doctors, or 54% of those trained in the period, left to work abroad.[142]

South Africa

Along with many African nations, South Africa has been experiencing human capital flight in the past 20 years, since the end of apartheid. This is believed to be potentially damaging for the regional economy,[143] and is arguably detrimental to the wellbeing of the region's poor majority, desperately reliant on the health care infrastructure because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.[144] The skills drain in South Africa tends to reflect racial contours exacerbated by Black Economic Empowerment policies, and has thus resulted in large White South African communities abroad.[145] The problem is further highlighted by South Africa's request in 2001 of Canada to stop recruiting its doctors and other highly skilled medical personnel.[146]

For the medical sector, the loss of return from investment for all doctors emigrating from South Africa is $1.41bn. The benefit to destination countries is huge: $2.7bn for the United Kingdom alone, without compensation.[147]

More recently, in a case of reverse brain drain a net 359,000 highly skilled South Africans returned to South Africa from foreign work assignments over a five-year period from 2008 to 2013. This was catalysed by the global financial crisis of 2007-8 and perceptions of a higher quality of life in South Africa relative to the countries to which they had first emigrated. It is estimated that around 37% of those who returned are professionals such as lawyers, doctors, engineers and accountants.[148]

Middle East

Iraq

During the Iraq War, especially during the early years, the lack of basic services and security fed an outflow of professionals from Iraq that began under Saddam Hussein, under whose rule four million Iraqis are believed to have left the country.[149] In particular, the exodus was fed by the violence that plagued Iraq, which by 2006 had seen 89 university professors and senior lecturers killed.[150]

Iran

In 2006, the International Monetary Fund ranked Iran "first in brain drain among 61 developing and less developed countries (LDC)"[151][152][153] In the early 1990s, more than 150,000 Iranians emigrated, and an estimated 25% of Iranians with post-secondary education were residing in developed countries of the OECD. In 2009, the International Monetary Fund reported that 150,000-180,000 Iranians emigrate annually, with up to 62% of Iran's academic elite having emigrated, and that the yearly exodus is equivalent to an annual capital loss of $50 billion.[154] Better possibilities for job markets is thought to be the motivation for absolute majority of the human capital flight while a small few stated their reasons as in search of more social or political freedom.[155][156]

Israel

Israel has experienced varying levels of emigration throughout its history, with the majority of Israeli expatriates moving to the United States. Currently, some 330,000 native-born Israelis (including 230,000 Israeli Jews) are estimated to be living abroad, while the number of immigrants to Israel who later left is unclear. According to public opinion polls, the main motives for leaving Israel have not been the political and security situation, but include desire for higher living standards, pursuit of work opportunities and/or professional advancement, and higher education. Many Israelis with degrees in scientific or engineering fields have emigrated abroad, largely due to lack of job opportunities. From Israel's establishment in May 1948 to December 2006, about 400,000 doctors and academics left Israel. In 2009, Israel's Council for Higher Education informed the Knesset's Education Committee that 25% of Israel's academics were living overseas, and that Israel had the highest human capital flight rate in the world. However, an OECD estimate put the highly educated Israeli emigrant rate at 5.3 per 1,000 highly educated Israelis, meaning that Israel actually retains more of its highly educated population than many other developed countries.

In addition, the majority of Israelis who emigrate eventually return after extended periods abroad. In 2007, the Israeli government began a programme to encourage Israelis living abroad to return; since then, the number of returning Israelis has doubled, and in 2010, Israeli expatriates, including academics, researchers, technical professionals, and business managers, began returning in record numbers. Israel launched additional programmes to open new opportunities in scientific fields to encourage Israeli scientists and researchers living abroad to return home. These programmes have since succeeded in luring many Israeli scientists back home.[157][158][159][160][161]

Arab world

By 2010, the Arab countries were experiencing human capital flight, according to reports from the United Nations and Arab League. About one million Arab experts and specialists were living in developed countries, and the rate of return was extremely low. The reasons for this included attraction to opportunities in technical and scientific fields in the West and an absence of job opportunities in the Arab world, as well as wars and political turmoil that have plagued many Arab nations.[162]

In 2012, human capital flight was showing signs of reversing, with many young students choosing to stay and more individuals from abroad returning. In particular, many young professionals are becoming entrepreneurs and starting their own businesses rather than going abroad to work for companies in Western countries. This was partially a result of the Arab Spring, after which many Arab countries began viewing science as the driving force for development, and as a result stepped up their science programmes. Another reason may be the ongoing global recession.[163][164]

Asia Pacific

Malaysia

There has been high rates of human capital flight from Malaysia. Major pull factors have included better career opportunities abroad and compensation, while major push factors included corruption, social inequality, educational opportunities,racial inequality such as the government's Bumiputera affirmative action policies. As of 2011, Bernama has reported that there are a million talented Malaysians working overseas.[165] Recently human capital flight has increased in pace: 305,000 Malaysians migrated overseas between March 2008 and August 2009, compared to 140,000 in 2007.[166] Non-Bumiputeras, particularly Malaysian Indians and Malaysian Chinese, were over-represented in these statistics. Popular destinations included Singapore, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom.[167] This is reported to have caused Malaysia's economic growth rate to fall to an average of 4.6% per annum in the 2000s compared to 7.2% in the 1990s.[168]

Philippines

Post-colonial Philippines

In 1946, colonialism in the Philippines ended with the election of Manuel Roxas.[169] The Philippines’ infrastructure and economy had been devastated by World War II, contributing to serious national health problems and uneven wealth distribution.[170] As part of reconstruction efforts for the newly independent state, education of nurses was encouraged to combat the low ratio of 1 nurse per 12,000 Filipinos[171] and to help raise national health care standards. However Roxas, having spent his last 3 years as the secretary of finance and chairman of the National Economic Council and a number of other Filipino companies, was particularly concerned with the country’s financial (rather than health) problems.[170] The lack of government funding for rural community clinics and hospitals, as well as low wages, continued to perpetuate low nurse retention rates in rural areas and slow economic recovery. When the United States relaxed their Immigration Act laws in 1965, labor export emerged as a possible solution for the Philippines.

Labour export from the 1960s on

Since the 1960s and 1970s, the Philippines has been the largest supplier of nurses to the United States, in addition to export labour supplied to the UK and Saudi Arabia.[172] In 1965, with a recovering post-WWII economy and facing labor shortages, the United States introduced a new occupational clause to the Immigration Act.[173] The clause encouraged migration of skilled labour into sectors experiencing a shortage,[173] particularly nursing, as well relaxing restrictions on race and origin.[174] This was seen as an opportunity for mass Filipino labour exportation by the Filipino government, and was followed by a boom in public and private nursing educational programmes. Seeking access through the U.S. government-sponsored Exchange Visitors Programme (EVP), workers were encouraged to go abroad to learn more skills and earn higher pay, sending remittance payments back home.[175] Nursing being regarded as a highly feminized profession, labour migrants have been predominantly female and young (25–30 years of age).[176]

Pursuing economic gains through labour migration over infrastructural financing and improvement, the Philippines still faced slow economic growth during the 1970s and 1980s.[177] With continuously rising demand for nurses in the international service sector and overseas, the Filipino government aggressively furthered their educational programmes under President Ferdinand Marcos, elected at this time. Although complete statistical data can be difficult to collect, studies done in the 1970s show 13,500 nurses (or 85% of all Filipino nurses) had left the country to pursue work elsewhere.[178] Additionally, public and private nursing school programmes multiplied from a reported 17 nursing schools in 1950, to 140 nursing schools in 1970.[179]

Remittances

Studies show stark wage discrepancies between the Philippines and developed countries such as the US and the UK. This has led Filipino government officials to note that remittances sent home may be seen as more economically valuable than pursuit of local work. Around the turn of the 20th century, the average monthly wage of Filipino nurses who remained in their home country was between 550 - 1000 pesos per month (roughly $70 – 140 US at that time).[180] In comparison, the average nurse working in the U.S. was receiving $800 – 1400 US per month.[180]

However, scholars have noted that economic disparities in the Philippines have not been eased in the past decades. Although remittance payments account for a large portion of Filipino GDP ($290.5 million US in 1978, increased to $10.7 billion US in 2005),[181] and are therefore regarded as a large economic boost to the state, Filipino unemployment has continued to rise (8.4% in 1990, increased to 12.7% in 2003).[181] Here scholars have begun to look at the culture of nurse migration endorsed by the Filipino state as a contributing factor to the country’s economic and health problems.

Migration culture of nursing

The Philippines spent only 3.6% of their GDP on health care and facilities in 2011, ranking them 170th in health spending according to the World Health Organization.[182] Their health system, particularly in rural areas, has been underfunded, understaffed and lacking advancements in health technologies, causing retention difficulties and poor access to services.[183] However, with reported figures of Filipino nursing graduates reaching 27,000 between 1999 and 2003, and jumping to a total of 26,000 in 2005 alone, there are clear discrepancies between skilled Filipino nurses and availability of health services in the country.[184] Scholars have pointed to the increasing privatization and commercialization of the nursing industry as a major reason for this loss of skill.

Migration has arguably become a “taken-for-granted” aspect of a nursing career, particularly with regard to the culture of migration that has been institutionally perpetuated in the health sector.[185] Most nursing schools have been built since the turn of the century and are concentrated primarily in metro Manila and other provincial cities. Of approximately 460 schools providing bachelor's degrees in nursing,[186] the majority are privately controlled, in part due to the inability of the Filipino government to keep up with rising education demand. However, private schooling has also been a lucrative business, fulfilling the dire need of Philippine labour looking for potential access to higher income.

Education industry

In addition to the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) run by the government as a source of overseas recruitment agreements, and as a marketer of Filipino labour overseas, private nursing schools have acted as migration funnels, expanding enrolment, asserting control over the licensure process, and entering into business agreements with other overseas recruitment agencies.[187] However, retaining qualified instructors and staff has been reported to be as problematic as retaining actual nurses, contributing to low exam pass rates (only 12 of 175 reporting schools had pass rates of 90% or higher in 2005,[188] with an average pass rate of 42% across the country in 2006).[189] Private schools have also begun to control licensure exam review centres, providing extra preparation for international qualification exams at extra cost and with no guarantee of success.[190] It is estimated that between 1999 and 2006, $700 million US was spent on nursing education and licensure review courses by individuals who never even took the licensing exams or were able to complete the programming.[190]

Discrepancies in wages between Filipino nurses working at home and those working abroad, as noted above, provide clear economic incentives for nurses to leave the country; however, physicians have also been lured into these promises of wealth through the creation of “Second Course” nursing programs.[191] Studies compare wages of Filipino nurses at home and abroad from 2005 to 2010, with at-home nurses receiving $170 US per month, or $2040 US per annum, compared to $3000–4000 US salary per month in the US, or $36,000-48,000 US per annum.[192] Filipino physician salaries for those working at home are not much more competitive; they earn on average $300–800 US per month, or $3600–9600 US per annum.[193] Although it is important to note along with such discrepancies that the costs of living are also higher in the US, and that remittance payment transfers back home are not free, there is still evidently a large economic pull to studying as a nurse and migrating overseas.

The push and pull, and the lasting effects

The Philippines’ colonial and post-WWII history contribute an understanding of the process by which nurses have increasingly turned to migration for greater economic benefits. Discussed in terms of numbers and financial gains, export labour migration has been suggested as a solution to the struggling Filipino economy, with labour transfers and remittance payments seen as beneficial for both countries.[194] However, since in 2004, 80% of all Filipino physicians had taken ‘second courses’ to retrain as nurses, it is suggested that export labour migration is undermining the national health sector of the country.[195]

With physicians and nurses leaving en masse for greater financial promise abroad, the ratio of nurses to patients in the Philippines has worsened from 1 nurse per 15-20 patients in 1990 to 1 nurse per 40-60 patients in 2007.[196] Additionally, the increase in private institution recruitment has evaded government oversight, and arguably has led to lower standards and working conditions for nurses actually working abroad. Once abroad, Filipino nurses have identified discriminatory workplace practices, receiving more night and holiday shifts, as well as more mundane tasks than non-Filipino counterparts.[197] Nurses also discuss the lack of opportunity to train and learn new skills, an enticement that is advertised by the Filipino export labour migration system.[198] Homesickness and lack of community integration can also cause great emotional duress on migrants, and with the majority of migrants female, family separation can cause negative impacts on both the migrants and their families.

Further critical enquiries into the success of export labour migration for the Philippines are needed. As noted, financial and economic statistics cannot fully describe the complexity of en-masse migration of nurses and physicians. It is important to understand the multitude of elements which combine to encourage a culture of migration. Brain-drain as a phenomenon can be currently applied to the Filipino situation; however, it is important to note, this does not suggest export labour migration as the primary causal factor of the country’s current economic situation. Lack of government funding for health care systems, in addition to the export labour migration culture, as well as other local factors, all contribute to what is described as the current brain-drain phenomenon occurring in the Philippines. It is important to understand the complexity of the nation’s history with regard to labour export and government funding in order to determine benefits, costs, and perpetuated problems within the society’s infrastructure.

South Asia

Nepal

Every year 250,000 youth are reported to leave Nepal for various reasons. They seek opportunity in its various manifestation — higher living standards, employment, better income, education, a luring western lifestyle, stability and security.[199] This number is expected to rise as a result of devastating earthquake on 25 April 2015.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has lost a significant portion of its intellectuals, mainly due to civil war and the resulting uncertainty that prevailed in the country for the thirty-year period prior to the end of the conflict in 2009. Most of these sought refuge in countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, and Great Britain. In recent years, many expatriates have indicated interest in returning to Sri Lanka, but have been deterred by slow economic growth and political instability. Both the government and private organizations are making efforts to encourage professionals to return to Sri Lanka and to retain resident intellectuals and professionals.

Eastern Asia

China

With rapid GDP growth and a higher degree of openness towards the rest of the world, there has been an upsurge in Chinese emigration to Western countries—particularly the United States, Canada and Australia.[200] China became the biggest worldwide contributor of emigrants in 2007. According to the official Chinese media, in 2009, 65,000 Chinese secured immigration or permanent resident status in the United States, 25,000 in Canada and 15,000 in Australia.[200] The largest group of emigrants consists of professionals and experts with a middle-class background,[200] who are the backbone for the development of China. According to a 2007 study, seven out of every ten students who enroll in an overseas university never return to live in their homeland.[201]

Since the beginning of the last century, international students were sent to different countries to learn advanced skills, and they were expected to return to save the nation from invasion and poverty. While most of these students came back to make a living, there were still those who chose to stay abroad. From the 1950s to the 1970s, China was in a period of widespread upheaval due to political instability. As a result, many Chinese felt upset and disappointed about the situation. The situation did not improve after the gradual liberalization of China during the 1980s; just as many people chose to go abroad, since there were more opportunities overseas. More social upheavals happened with the Tiananmen Square Massacre—the result of which was an increasing Chinese diaspora. As steady economic growth boosts GDP per capita, more families in China are able to pay for their children to go abroad for study or to live.

Australasia

Pacific Islands

The post-WWII migration trends in the Pacific Islands have essentially followed this pattern:

- Most Pacific island nations that were formerly under UK mandate have had migration outflows to Australia and New Zealand since the de-colonialization of the region from the 1960s to the 1990s. There has only been a limited outflow from these islands to Canada and the UK since de-colonialization. Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa also have had large outflows to the United States.

- Most Pacific islands administered by France (like Tahiti) have had an outflow to France.

- Most Pacific islands under some kind of US administration have had outflows to the US, and to a lesser extent, Canada.

New Zealand

During the 1990s, 30,000 New Zealanders were emigrating each year. An OECD report released in 2005 revealed that 24.2% of New Zealanders with a tertiary education were living outside of New Zealand, predominantly in Australia.[202] In 2007, around 24,000 New Zealanders settled in Australia.[203]

During the 2008 election campaign, the National Party campaigned on the ruling Labour Party's inability to keep New Zealanders at home, with a series of billboards announcing "Wave goodbye to higher taxes, not your loved ones".[204] However, four years after the National Party won that election, the exodus to Australia had intensified, surpassing 53,000 per annum in 2012.[205] Prime Minister John Key blamed the global financial crisis for the continuing drain.[206]

It was estimated in December 2012 that 170,000 New Zealanders had left for Australia since the Key government came to power in late 2008.[207] However, this net migration was reversed soon after, with a net migration gain of 1,933 people achieved in 2016. [208] Reasons for this reversal have been theorized by economists, citing New Zealand's housing and construction boom at the time [209] Australia's political instability and reduced investment in mining industries during this time was also mentioned as a key factor.

New Zealand enjoys immigration of qualified foreigners, potentially leaving a net gain of skills.[210] Nevertheless, one reason for New Zealand's attempt to target immigration at 1% of its population per year is because of its high rate of emigration, which leaves its migration balance either neutral or slightly positive.

North America

Canada

Colonial administrators in Canada observed the trend of human capital flight to the United States as early as the 1860s, when it was already clear that a majority of immigrants arriving at Quebec City were en route to destinations in the United States. Alexander C. Buchanan, government agent at Quebec, argued that prospective emigrants should be offered free land to remain in Canada. The issue of attracting and keeping the right immigrants has sometimes been central to Canada's immigration history.[211]

In the 1920s, over 20% of university graduating classes in engineering and science were emigrating to the United States. When governments displayed no interest, concerned industrialists formed the Technical Service Council in 1927 to combat the "brain drain". As a practical means of doing so, the council operated a placement service that was free to graduates.

By 1976, the council had placed over 16,000 men and women. Between 1960 and 1979 over 17,000 engineers and scientists emigrated to the United States. However, the exodus of technically trained Canadians dropped from 27% of graduating classes in 1927 to under 10% in 1951 and 5% in 1967.

In Canada today, the idea of a "brain drain" to the United States is occasionally a domestic political issue. At times, "brain drain" is used as a justification for income tax cuts. During the 1990s, some alleged a "brain drain" from Canada to the United States, especially in the software, aerospace, health care and entertainment industries, due to the perception of higher wages and lower income taxes in the US.[212] Some also suggest that engineers and scientists were also attracted by the greater diversity of jobs and a perceived lack of research funding in Canada.

The evidence suggests that, in the 1990s, Canada did lose some of its homegrown talent to the US.[213] Nevertheless, Canada hedged against these losses by attracting more highly skilled workers from abroad. This allowed the country to realize a net brain gain as more professionals entered Canada than left.[213] Sometimes, the qualifications of these migrants are given no recognition in Canada (see credentialism), resulting in some - though not all - highly skilled professionals being forced into lower paying service sector jobs.

In the mid-2000s, Canada's resilient economy, strong domestic market, high standard of living, and considerable wage growth across a number of sectors, effectively ended the brain drain debate.[214][215] Canada's economic success even prompted some top US talent to migrate north.[214][215][216][217][218] Anecdotal evidence also suggests that stringent US security measures put in place after 11 September 2001 have helped to temper the brain drain debate in Canada.[219]

United States

The 2000 United States Census led to a special report on domestic worker migration, with a focus on the movement of young, single, college-educated migrants.[220] The data show a trend of such people moving away from the Rust Belt and northern Great Plains region towards the West Coast, Southwestern United States and Southeast. The largest net influx of young, single, college-educated persons was San Francisco Bay.

The country as a whole does not experience large-scale human capital flight as compared with other countries, with an emigration rate of only 0.7 per 1,000 educated people,[221] but it is often the destination of skilled workers migrating from elsewhere in the world.[222]

Regarding foreign scholars earning their degrees in the United States and return to their home country, Danielle Guichard-Ashbrook of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has been quoted as stating "We educate them, but then we don't make it easy for them to stay".[223]

Central and South America

Cuba

In 1997, Cuban officials claimed that 31,000 Cuban doctors were deployed in 61 countries.[224] A large number practice in South America. In 2007, it was reported that 20,000 were employed in Venezuela in exchange for nearly 100,000 barrels (16,000 m3) of oil per day.[225]

However, in Venezuela and Bolivia, where another 1,700 doctors work, it is stated that as many as 500 doctors may have fled the missions in the years preceding 2007 into countries nearby.[224] This number raised to dramatically, with 1,289 visas being given to Cuban medical professionals in the United States alone in 2014, with the majority of Cuban medical personnel fleeing from Venezuela due to poor social conditions and not receiving adequate payment; the Cuban government allegedly receives the majority of payments while some doctors are left with about $100 per month in earnings.[226]

Venezuela

Following the election of Hugo Chávez as president and his establishment of the Bolivarian Revolution, millions of Venezuelans emigrated from Venezuela.[227][228][229] In 2009, it was estimated that more than 1 million Venezuelan emigrated since Hugo Chávez became president.[228] It has been calculated that from 1998 to 2013, over 1.5 million Venezuelans, between 4% and 6% of the Venezuela's total population, left the country following the Bolivarian Revolution.[229] Academics and business leaders have stated that emigration from Venezuela increased significantly during the last years of Chávez's presidency and especially during the presidency of Nicolás Maduro.[230]

The analysis of a study by the Central University of Venezuela titled Venezuelan Community Abroad. A New Method of Exile states that the Bolivarian diaspora was caused by the "deterioration of both the economy and the social fabric, rampant crime, uncertainty and lack of hope for a change in leadership in the near future".[227] The Wall Street Journal stated that many "white-collar Venezuelans have fled the country's high crime rates, soaring inflation and expanding statist controls".[231] Many of the former Venezuelan citizens studied gave reasons for leaving Venezuela that included lack of freedom, high levels of insecurity and lack of opportunity in the country.[229][232]

In the Venezuelan Community Abroad. A New Method of Exile study, of the more than 1.5 million Venezuelans who had left the country following the Bolivarian Revolution, more than 90% of those who left were college graduates, with 40% holding a Master's degree and 12% having a doctorates and post doctorates.[229][232] Some Venezuelan parents encourage their children to leave the country.[229]

Caribbean

Many of the Caribbean Islands endure a substantial emigration of qualified workers. Approximately 30% of the labour forces of many islands have left, and more than 80% of college graduates from Suriname, Haiti, Grenada and Guyana have emigrated, mostly to the United States.[233] Over 80% of Jamaicans with higher education live abroad.[234] However, it is noted that these nationals pay valuable remittances. In Jamaica, the money sent back amounts to 18% of GNP.[235]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Baptiste, Nathalie (25 February 2014). "Brain Drain and the Politics of Immigration". Foreign Policy In Focus. Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

The migration of highly skilled workers can pay dividends for immigrants and their employers, but it produces losers as well.

- ↑ Birrell, Bob (8 March 2016). "Australia's Skilled Migration Program: Scarce Skills Not Required" (PDF). The Australian Population Research Institute. Monash University. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ↑ di Giovanni, Julian; Levchenko, Andrei A.; Ortega, Francesc (1 February 2015). "A Global View of Cross-Border Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 168–202. doi:10.1111/jeea.12110. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Andreas, Willenbockel, Dirk; Sia, Go, Delfin; Amer, Ahmed, S. (11 April 2016). "Global migration revisited : short-term pains, long-term gains, and the potential of south-south migration".

- ↑ "The Gain from the Drain - Skill-biased Migration and Global Welfare" (PDF).

- ↑ Khanna, Gaurav; Morales, Nicolas (30 April 2017). "The IT Boom and Other Unintended Consequences of Chasing the American Dream". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ Hillel, Rapoport (20 September 2016). "Migration and globalization: what's in it for developing countries?". International Journal of Manpower. 37 (7): 1209–1226. doi:10.1108/IJM-08-2015-0116. ISSN 0143-7720.

- ↑ Shrestha, Slesh A. (1 April 2016). "No Man Left Behind: Effects of Emigration Prospects on Educational and Labour Outcomes of Non-migrants". The Economic Journal. 127 (600): n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12306. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Beine, Michel; Docquier, Fréderic; Rapoport, Hillel (1 April 2008). "Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers". The Economic Journal. 118 (528): 631–652. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Dinkelman, Taryn; Mariotti, Martine (2016). "The Long-Run Effects of Labor Migration on Human Capital Formation in Communities of Origin". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 8 (4): 1–35. doi:10.1257/app.20150405.

- ↑ Batista, Catia; Lacuesta, Aitor; Vicente, Pedro C. (1 January 2012). "Testing the 'brain gain' hypothesis: Micro evidence from Cape Verde". Journal of Development Economics. 97 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.005.

- ↑ "Skilled Emigration and Skill Creation: A quasi-experiment - Working Paper 152". Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ↑ Barsbai, Toman; Rapoport, Hillel; Steinmayr, Andreas; Trebesch, Christoph (2017). "The Effect of Labor Migration on the Diffusion of Democracy: Evidence from a Former Soviet Republic". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 9 (3): 36. doi:10.1257/app.20150517.

- ↑ Ivlevs, Artjoms; King, Roswitha M. "Does emigration reduce corruption?". Public Choice. 171. doi:10.1007/s11127-017-0442-z.

- ↑ "Migration, Political Institutions, and Social Networks in Mozambique".

- ↑ Lodigiani, Elisabetta. "The effect of emigration on home-country political institutions". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.307.

- ↑ Meseguer, C.; Burgess, K. (2014). "International Migration and Home Country Politics". Studies in Comparative International Development. Springer US. 49 (1): 1–12. ISSN 1936-6167.

- ↑ Docquier, Frédéric; Lodigiani, Elisabetta; Rapoport, Hillel; Schiff, Maurice. "Emigration and democracy" (PDF). Bar-Ilan University.

- ↑ Burgess, Katrina (2012). "Migrants, Remittances, and Politics: Loyalty and Voice after Exit" (PDF). The Fletcher forum of world affairs. 36 (1): 43–55.

- ↑ Ratha, Dilip Mohapatra; Sanket Scheja, Elina (2011). Impact of Migration on Economic and Social Development: A review of evidence and emerging issues (PDF).

Migrants may also serve as a channel for democratic attitudes and behaviors...

- ↑ Batista, Catia; Vicente, Pedro C. (1 January 2011). "Do Migrants Improve Governance at Home? Evidence from a Voting Experiment". The World Bank Economic Review. 25 (1): 77–104. doi:10.1093/wber/lhr009. ISSN 0258-6770.

- ↑ Cervantes, Mario; Guellec, Dominique (January 2002). "The brain drain: Old myths, new realities". OECD Observer. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Joel Spring. Globalization of Education: an introduction. First published 2009, by Routledge, 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016, pp185

- ↑ "Brain drain - Definition and More", Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2010, web: MW-b.

- 1 2 Yvonne Stolz and Joerg Baten " Brain Drain, Numeracy and Skill Premia during the Era of Mass Migration: Testing the Roy-Borjas Model"

- ↑ Clemens, Michael (2015). "CSAE Conference 2015 Plenary 3: Migration and Labour Mobility". Starts at 19:35.

- ↑ Clemens, Michael. "Why It's Time to Drop the 'Brain Drain' Refrain". Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- 1 2 Clemens, Michael; Development, Center for Global; USA (2015). "Smart policy toward high-skill emigrants". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.203.

- 1 2 "Migration and Development: Who Bears the Burden of Proof? Justin Sandefur replies to Paul Collier | From Poverty to Power". oxfamblogs.org. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ↑ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg. "Myths of Migration: Much of What We Think We Know Is Wrong - SPIEGEL ONLINE - International". SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ↑ Haas, Hein De (1 November 2005). "International migration, remittances and development: myths and facts". Third World Quarterly. 26 (8): 1269–1284. doi:10.1080/01436590500336757. ISSN 0143-6597.

- 1 2 Docquier, Frédéric; (UCLouvain), IRES; Belgium (1 May 2014). "The brain drain from developing countries". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.31.

- 1 2 di Giovanni, Julian; Levchenko, Andrei A.; Ortega, Francesc (1 February 2015). "A Global View of Cross-Border Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 168–202. doi:10.1111/jeea.12110. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Andreas, Willenbockel, Dirk; Sia, Go, Delfin; Amer, Ahmed, S. (11 April 2016). "Global migration revisited : short-term pains, long-term gains, and the potential of south-south migration".

- ↑ "The Gain from the Drain - Skill-biased Migration and Global Welfare" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 Khanna, Gaurav; Morales, Nicolas (30 April 2017). "The IT Boom and Other Unintended Consequences of Chasing the American Dream". Rochester, NY.

- 1 2 Clemens, Michael A.; Pritchett, Lant (February 2016). "The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment". IZA Discussion Paper No. 9730. SSRN 2731993.

- ↑ McKenzie, David; Stillman, Steven; Gibson, John (1 June 2010). "How Important is Selection? Experimental VS. Non-Experimental Measures of the Income Gains from Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 8 (4): 913–945. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00544.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- 1 2 Gove, Michael (18 April 2017). "Migration as Development: Household Survey Evidence on Migrants' Wage Gains". Social Indicators Research: 1–28. doi:10.1007/s11205-017-1630-4. ISSN 0303-8300.

- 1 2 Ratha, Dilip; Silwal (2012). "Remittance flows in 2011" (PDF). Migration and Development Brief –Migration and Remittances Unit, the World Bank. 18: 1–3.

- ↑ "Global Remittances Guide". migrationpolicy.org. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ↑ Mergo, Teferi (1 August 2016). "The Effects of International Migration on Migrant-Source Households: Evidence from Ethiopian Diversity-Visa Lottery Migrants". World Development. 84: 69–81. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.04.001.

- ↑ Adida, Claire L.; Girod, Desha M. (1 January 2011). "Do Migrants Improve Their Hometowns? Remittances and Access to Public Services in Mexico, 1995-2000". Comparative Political Studies. 44 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1177/0010414010381073. ISSN 0010-4140.

- ↑ Mbaye, Linguère Mously; Drabo, Alassane (1 December 2017). "Natural Disasters and Poverty Reduction: Do Remittances Matter?". CESifo Economic Studies. 63 (4): 481–499. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifx016. ISSN 1610-241X.

- ↑ Bollard, Albert; McKenzie, David; Morten, Melanie; Rapoport, Hillel (1 January 2011). "Remittances and the Brain Drain Revisited: The Microdata Show That More Educated Migrants Remit More". World Bank Economic Review. 25 (1): 132–156. doi:10.1093/wber/lhr013.

- ↑ di Giovanni, Julian; Levchenko, Andrei A.; Ortega, Francesc (1 February 2015). "A Global View of Cross-Border Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 168–202. doi:10.1111/jeea.12110. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Anelli, Massimo; Peri, Giovanni (2017). "Does Emigration Delay Political Change? Evidence from Italy during the Great Recession". Economic Policy. 32 (91): 551–596. doi:10.1093/epolic/eix006.

- ↑ Wahba, Jackline; Southampton, University of; UK (1 February 2015). "Who benefits from return migration to developing countries?". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.123.

- ↑ Iregui, Ana Maria (1 January 2003). "Efficiency Gains from the Elimination of Global Restrictions on Labour Mobility: An Analysis using a Multiregional CGE Model".

- ↑ Clemens, Michael A (1 August 2011). "Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 25 (3): 83–106. doi:10.1257/jep.25.3.83. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Hamilton, B.; Whalley, J. (1 February 1984). "Efficiency and distributional implications of global restrictions on labour mobility: calculations and policy implications". Journal of Development Economics. 14 (1–2): 61–75. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(84)90043-9. ISSN 0304-3878. PMID 12266702.

- ↑ Aner, Emilie; Graneli, Anna; Lodefolk, Magnus (14 October 2015). "Cross-border movement of persons stimulates trade". VoxEU.org. Centre for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Bratti, Massimiliano; Benedictis, Luca De; Santoni, Gianluca (18 April 2014). "On the pro-trade effects of immigrants". Review of World Economics. 150 (3): 557–594. doi:10.1007/s10290-014-0191-8. ISSN 1610-2878.

- ↑ Foley, C. Fritz; Kerr, William R. (2013). "Ethnic Innovation and U.S. Multinational Activity". Management Science. 59 (7): 1529–1544. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1120.1684.

- ↑ Burchardi, Konrad B.; Chaney, Thomas; Hassan, Tarek A. (January 2016). "Migrants, Ancestors, and Investment". NBER Working Paper No. 21847. doi:10.3386/w21847.

- ↑ Javorcik, Beata S.; Özden, Çaglar; Spatareanu, Mariana; Neagu, Cristina (1 January 2011). "Migrant networks and foreign direct investment". Journal of Development Economics. 94 (2): 231–241. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.012.

- ↑ Tong, Sarah Y. (1 November 2005). "Ethnic Networks in FDI and the Impact of Institutional Development". Review of Development Economics. 9 (4): 563–580. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9361.2005.00294.x. ISSN 1467-9361.

- ↑ Kugler, Maurice; Levintal, Oren; Rapoport, Hillel (2017). "Migration and Cross-Border Financial Flows". The World Bank Economic Review. doi:10.1093/wber/lhx007.

- ↑ "Migration and Globalization: What's in it for Developing Countries?" (PDF).

- ↑ Hillel Rapoport (20 September 2016). "Migration and globalization: what's in it for developing countries?". International Journal of Manpower. 37 (7): 1209–1226. doi:10.1108/IJM-08-2015-0116. ISSN 0143-7720.

- ↑ "Emigration and wages in source countries: a survey of the empirical literature : International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development". www.elgaronline.com. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- ↑ Dustmann, Christian; Frattini, Tommaso; Rosso, Anna (1 April 2015). "The Effect of Emigration from Poland on Polish Wages". The Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 117 (2): 522–564. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12102. ISSN 1467-9442.

- ↑ Elsner, Benjamin (1 September 2013). "Emigration and wages: The EU enlargement experiment". Journal of International Economics. 91 (1): 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.06.002.

- ↑ Elsner, Benjamin (10 November 2012). "Does emigration benefit the stayers? Evidence from EU enlargement". Journal of Population Economics. 26 (2): 531–553. doi:10.1007/s00148-012-0452-6. ISSN 0933-1433.

- ↑ "The effects of return migration on Egyptian household revenues".

- ↑ Shrestha, Slesh A. (1 April 2016). "No Man Left Behind: Effects of Emigration Prospects on Educational and Labour Outcomes of Non-migrants". The Economic Journal. 127 (600): n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12306. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Beine, Michel; Docquier, Fréderic; Rapoport, Hillel (1 April 2008). "Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers". The Economic Journal. 118 (528): 631–652. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Dinkelman, Taryn; Mariotti, Martine (2016). "The Long-Run Effects of Labor Migration on Human Capital Formation in Communities of Origin". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 8 (4): 1–35. doi:10.1257/app.20150405.

- ↑ Batista, Catia; Lacuesta, Aitor; Vicente, Pedro C. (1 January 2012). "Testing the 'brain gain' hypothesis: Micro evidence from Cape Verde". Journal of Development Economics. 97 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.005.

- ↑ "Skilled Emigration and Skill Creation: A quasi-experiment - Working Paper 152". Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- 1 2 Xu, Rui (March 2016). "High-Skilled Migration and Global Innovation" (PDF). SIEPR Discussion Paper No. 16-016.

- 1 2 "Stop blaming the H-1B visa for India's brain drain—it actually achieved the opposite". Quartz. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ Agrawal, Ajay; Kapur, Devesh; McHale, John; Oettl, Alexander (1 January 2011). "Brain drain or brain bank? The impact of skilled emigration on poor-country innovation". Journal of Urban Economics. 69 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2010.06.003.

- ↑ Docquier, Frédéric; Lodigiani, Elisabetta; Rapoport, Hillel; Schiff, Maurice (1 May 2016). "Emigration and democracy". Journal of Development Economics. 120: 209–223. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.12.001.

- ↑ Escribà-Folch, Abel; Meseguer, Covadonga; Wright, Joseph (1 September 2015). "Remittances and Democratization". International Studies Quarterly. 59 (3): 571–586. doi:10.1111/isqu.12180. ISSN 1468-2478.

- ↑ "Mounir Karadja". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- ↑ "Can emigration lead to political change in poor countries? It did in 19th century Sweden: Guest Post by Mounir Karadja". Impact Evaluations. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- ↑ Tuccio, Michele; Wahba, Jackline; Hamdouch, Bachir (1 January 2016). "International Migration: Driver of Political and Social Change?". Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- 1 2 "Migration, Political Institutions, and Social Networks in Mozambique".

- ↑ Batista, Catia; Vicente, Pedro C. (1 January 2011). "Do Migrants Improve Governance at Home? Evidence from a Voting Experiment". The World Bank Economic Review. 25 (1): 77–104. doi:10.1093/wber/lhr009. ISSN 0258-6770.

- ↑ Pfutze, Tobias (1 June 2014). "Clientelism Versus Social Learning: The Electoral Effects of International Migration". International Studies Quarterly. 58 (2): 295–307. doi:10.1111/isqu.12072. ISSN 1468-2478.

- ↑ Beine, Michel; Sekkat, Khalid (19 June 2013). "Skilled migration and the transfer of institutional norms". IZA Journal of Migration. 2 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1186/2193-9039-2-9. ISSN 2193-9039.

- ↑ Barsbai, Toman; Rapoport, Hillel; Steinmayr, Andreas; Trebesch, Christoph (2017). "The Effect of Labor Migration on the Diffusion of Democracy: Evidence from a Former Soviet Republic". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 9 (3): 36. doi:10.1257/app.20150517.

- ↑ Chauvet, Lisa; Mercier, Marion (1 August 2014). "Do return migrants transfer political norms to their origin country? Evidence from Mali". Journal of Comparative Economics. 42 (3): 630–651. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2014.01.001.

- ↑ Pérez-Armendáriz, Clarisa; Crow, David (1 January 2010). "Do Migrants Remit Democracy? International Migration, Political Beliefs, and Behavior in Mexico". Comparative Political Studies. 43 (1): 119–148. doi:10.1177/0010414009331733. ISSN 0010-4140.

- ↑ Regan, Patrick M.; Frank, Richard W. (1 November 2014). "Migrant remittances and the onset of civil war". Conflict Management and Peace Science. 31 (5): 502–520. doi:10.1177/0738894213520369. ISSN 0738-8942.

- ↑ Bove, Vincenzo; Böhmelt, Tobias (11 February 2016). "Does Immigration Induce Terrorism?". The Journal of Politics. 78 (2): 572–588. doi:10.1086/684679. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ↑ Tuccio, Michele; Wahba, Jackline (4 September 2015). "Can I Have Permission to Leave the House? Return Migration and the Transfer of Gender Norms". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2655237.

- ↑ Lodigiani, Elisabetta; Salomone, Sara (23 June 2015). "Migration-Induced Transfers of Norms. The Case of Female Political Empowerment". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2622394.

- ↑ Ferrant, Gaëlle; Tuccio, Michele (1 August 2015). "South–South Migration and Discrimination Against Women in Social Institutions: A Two-way Relationship". World Development. 72: 240–254. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.002.

- ↑ Spilimbergo, Antonio (1 March 2009). "Democracy and Foreign Education". American Economic Review. 99 (1): 528–543. doi:10.1257/aer.99.1.528. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ↑ Gift, Thomas; Krcmaric, Daniel (31 July 2015). "Who Democratizes? Western-educated Leaders and Regime Transitions". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 61 (3): 0022002715590878. doi:10.1177/0022002715590878. ISSN 0022-0027.

- ↑ Mercier, Marion (1 September 2016). "The return of the prodigy son: Do return migrants make better leaders?". Journal of Development Economics. 122: 76–91. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.04.005.

- ↑ Tai, Qiuqing (2 January 2016). "Western Media Exposure and Chinese Immigrants' Political Perceptions". Political Communication. 33 (1): 78–97. doi:10.1080/10584609.2014.978921. ISSN 1058-4609.

- ↑ Tyburski, Michael D. (1 July 2014). "Curse or Cure? Migrant Remittances and Corruption". The Journal of Politics. 76 (3): 814–824. doi:10.1017/S0022381614000279. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ↑ Lu, Yao; Tao, Ran (4 March 2015). "Female Migration, Cultural Context, and Son Preference in Rural China". Population Research and Policy Review. 34 (5): 665–686. doi:10.1007/s11113-015-9357-x. ISSN 0167-5923.

- ↑ Richard Sorabji, (2005), The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200–600 AD: Psychology (with Ethics and Religion), page 11. Cornell University Press

- ↑ "The Expulsion from Spain, 1492 CE". Jewish History Sourcebook. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed, Frank Puaux, Huguenot

- ↑ "Franschhoek - Cape Town wine region". Cape-town.info. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Moser, Petra; Voena, Alessandra; Waldinger, Fabian (2014). "German Jewish Émigrés and US Invention". American Economic Review. 104 (10): 3222–3255. doi:10.1257/aer.104.10.3222.

- ↑ Dowty 1989, p. 69

- ↑ Dowty 1989, p. 74

- 1 2 Thackeray 2004, p. 188

- ↑ Dowty 1989, p. 114

- 1 2 Harrison 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Dowty 1989, p. 121

- 1 2 Dowty 1989, p. 122

- 1 2 3 Harrison 2003, p. 100

- ↑ Volker Rolf Berghahn, Modern Germany: Society, Economy and Politics in the Twentieth Century, p. 227. Cambridge University Press, 1987

- ↑ Pearson 1998, p. 75

- ↑ Jeff, Chu (11 January 2004). "How To Plug Europe's Brain Drain". TIME. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ↑ Stenman, Jim (28 June 2006). "Europe fears brain drain to UK". CNN. Retrieved 2008-06-01.